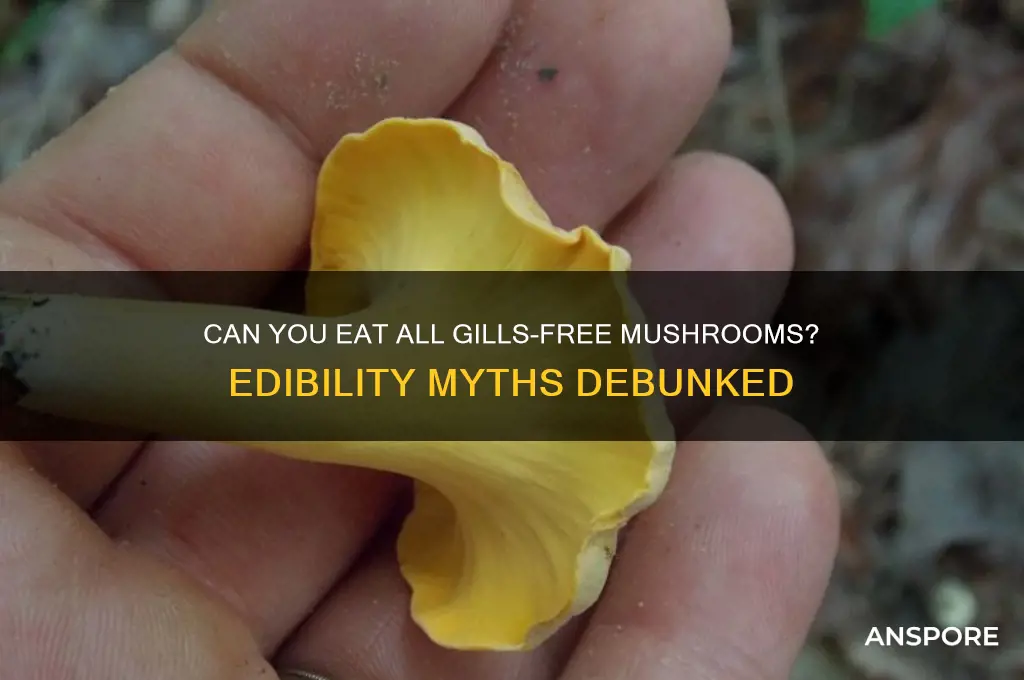

The question of whether all mushrooms without gills are edible is a common one, but it’s important to approach it with caution. While some gilled mushrooms are toxic, the absence of gills does not automatically make a mushroom safe to eat. Mushrooms without gills, such as puffballs, chanterelles, and boletes, can indeed be edible, but they also include poisonous species like the Amanita genus. Proper identification is crucial, as many toxic mushrooms lack gills but can still cause severe illness or even be fatal if consumed. Always consult a reliable field guide or expert before foraging, as relying solely on physical characteristics like gills can lead to dangerous mistakes.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| All mushrooms without gills are edible | False. While some mushrooms without gills are edible, many are toxic or poisonous. |

| Examples of edible gilled mushrooms | Chanterelles, morels, truffles, lion's mane, oyster mushrooms |

| Examples of toxic/poisonous gilled mushrooms | Amanita species (e.g., Death Cap, Destroying Angel), false morels, some Russula species |

| Key factors determining edibility | Mushroom species, proper identification, preparation methods, individual allergies |

| Common non-gilled mushroom types | Puffballs, coral fungi, bracket fungi, cup fungi, earthstars |

| Edible non-gilled mushrooms | Some puffballs (e.g., Giant Puffball), certain bracket fungi (e.g., Chicken of the Woods), some coral fungi |

| Toxic non-gilled mushrooms | Some Amanita species (e.g., Amanita ocreata), certain bracket fungi, false puffballs |

| Reliable identification methods | Field guides, expert consultation, spore prints, microscopic analysis |

| General rule | Never consume a wild mushroom without 100% certainty of its identification and edibility. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Gilled vs. Non-Gilled Mushrooms: Understanding structural differences and their implications for edibility

- Common Non-Gilled Edible Species: Examples like chanterelles, morels, and puffballs

- Toxic Non-Gilled Mushrooms: Identifying poisonous species without gills, such as Amanita species

- Edibility Testing Methods: Safe practices for determining if a non-gilled mushroom is edible

- Ecological Roles of Non-Gilled Mushrooms: Their importance in ecosystems beyond human consumption

Gilled vs. Non-Gilled Mushrooms: Understanding structural differences and their implications for edibility

Mushrooms without gills often spark curiosity about their edibility, but their structural differences from gilled varieties demand careful consideration. Non-gilled mushrooms, such as puffballs, chanterelles, and morels, lack the radiating spore-bearing structures found in gilled species like agarics. This absence of gills doesn't automatically render them safe to eat. For instance, the Amanita ocreata, a deadly gilled mushroom, contrasts sharply with the edible, non-gilled lion’s mane. Understanding these structural distinctions is crucial, as it highlights that edibility depends on species-specific traits, not just the presence or absence of gills.

Analyzing the anatomy of gilled and non-gilled mushrooms reveals why structure matters. Gilled mushrooms, like the common button mushroom (Agaricus bisporus), release spores from the underside of their caps, a feature that can sometimes correlate with toxicity in certain species. Non-gilled mushrooms, however, disperse spores through alternative mechanisms—puffballs explode them, while chanterelles use forked ridges. This diversity in spore dispersal doesn’t inherently indicate safety. For example, the non-gilled false morel (Gyromitra spp.) contains toxins that require thorough cooking to neutralize, while the gilled ink cap (Coprinus comatus) is edible. Thus, structural differences are a starting point, not a definitive guide to edibility.

Foraging safely requires a methodical approach, especially when distinguishing between gilled and non-gilled mushrooms. Start by identifying key features: gills, ridges, or pores. Non-gilled mushrooms often have smoother undersides or unique structures like the honeycomb pattern of morels. However, rely on multiple identifiers—color, habitat, and odor—to confirm species. For instance, the non-gilled shaggy mane has a distinct spicy smell, while the gilled death cap (Amanita phalloides) emits a sweet, deceptive aroma. Always cross-reference findings with reputable guides or consult experts, as misidentification can be fatal.

Practical tips for assessing edibility focus on caution and knowledge. Avoid consuming any mushroom unless you’re 100% certain of its identity. Non-gilled varieties like the giant puffball (Calvatia gigantea) are generally safer bets for beginners, but even these can be confused with poisonous look-alikes. Cooking methods matter too—boiling false morels for at least 15 minutes reduces toxins, though this doesn’t apply to all species. Lastly, start small: consume a minimal amount (e.g., one bite) and wait 24 hours to check for adverse reactions before eating more. This cautious approach ensures that structural differences guide, but don’t dictate, your foraging decisions.

Are All Oyster Mushrooms Edible? A Comprehensive Guide to Safety

You may want to see also

Common Non-Gilled Edible Species: Examples like chanterelles, morels, and puffballs

Not all mushrooms without gills are edible, but several non-gilled species are prized for their flavor, texture, and culinary versatility. Among these, chanterelles, morels, and puffballs stand out as prime examples. Unlike gilled mushrooms, which rely on a fan-like structure to disperse spores, these species use alternative methods—such as pores, ridges, or explosive mechanisms—to reproduce. This distinction not only shapes their appearance but also influences their habitat and foraging characteristics. Understanding these unique traits is key to identifying and safely enjoying these edible treasures.

Chanterelles, with their wavy caps and forked ridges, are a forager’s delight. Found in wooded areas, particularly under conifers and hardwoods, they thrive in moist, organic-rich soil. Their golden-yellow hue and fruity aroma make them unmistakable. When preparing chanterelles, clean them gently with a brush or damp cloth to preserve their delicate texture. Sautéing in butter or cream enhances their earthy flavor, making them a perfect addition to pasta, risotto, or omelets. Avoid overcooking, as this can cause them to become rubbery. Always cook chanterelles thoroughly, as consuming them raw can lead to digestive discomfort.

Morels, with their honeycomb-like caps, are another non-gilled delicacy. These springtime mushrooms favor disturbed soil, often appearing near ash trees or recently burned areas. Their distinct appearance reduces the risk of confusion with toxic look-alikes, but proper identification is still crucial. Morels should always be cooked to eliminate trace toxins and improve digestibility. A simple preparation—sautéing in butter with garlic and herbs—highlights their rich, nutty flavor. Drying morels preserves their essence and allows for year-round use; rehydrate them in warm water or broth before cooking. Never eat morels raw, as they can cause nausea and other adverse effects.

Puffballs, spherical and smooth, are among the easiest non-gilled mushrooms to identify. Found in grassy fields or woodland edges, they release spores through a small pore or by rupturing when mature. Young, firm puffballs with solid white interiors are ideal for consumption. Slice them thinly and fry or stuff them for a meaty texture reminiscent of portobello mushrooms. Avoid older specimens, which turn yellowish-brown and powdery inside, as these are inedible and may cause irritation. Always cut a puffball in half to confirm its edibility; any gills or discoloration indicate a different, potentially toxic species.

While these non-gilled species offer culinary rewards, caution is paramount. Misidentification can lead to severe poisoning, so rely on field guides, expert advice, or local mycological clubs when foraging. Start with easily recognizable species like puffballs before advancing to more complex varieties. Always cook non-gilled mushrooms thoroughly, as many contain compounds that are neutralized by heat. By respecting these guidelines, foragers can safely enjoy the unique flavors and textures of chanterelles, morels, and puffballs, enriching their culinary repertoire with nature’s bounty.

Are Ink Cap Mushrooms Edible? A Guide to Safe Foraging

You may want to see also

Toxic Non-Gilled Mushrooms: Identifying poisonous species without gills, such as Amanita species

Not all mushrooms without gills are safe to eat, and assuming so can be a dangerous mistake. While many non-gilled mushrooms are indeed edible, some of the most toxic fungi in the world lack gills. Among these, the *Amanita* genus stands out as a prime example of deadly non-gilled mushrooms. Species like the *Amanita ocreata* (Death Angel) and *Amanita phalloides* (Death Cap) are notorious for their potent toxins, which can cause severe liver and kidney damage, often leading to death if consumed. These mushrooms often resemble harmless varieties, making accurate identification critical.

Identifying toxic non-gilled mushrooms requires careful observation of specific characteristics. *Amanita* species, for instance, typically have a bulbous base, a ring (partial veil) on the stem, and white spores. Their caps are often smooth and can range in color from white to green or brown. However, relying solely on color or shape is risky, as these features can vary. Instead, look for the presence of a volva (a cup-like structure at the base) and a ring, which are hallmark features of many *Amanita* species. If you encounter a mushroom with these traits, avoid consumption and consider it potentially lethal until proven otherwise.

A common misconception is that boiling or cooking toxic mushrooms neutralizes their toxins. This is false, especially for *Amanita* species, whose toxins (amatoxins) remain active even after prolonged cooking. Ingesting as little as half a *Death Cap* can be fatal for an adult, and symptoms may not appear until 6–24 hours after consumption, delaying treatment. Children are particularly vulnerable due to their lower body weight, and even small amounts can be life-threatening. If you suspect poisoning, seek immediate medical attention and, if possible, bring a sample of the mushroom for identification.

To safely forage non-gilled mushrooms, adopt a cautious and informed approach. Always cross-reference findings with reliable field guides or consult an expert. Avoid consuming any mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity. Apps and online resources can be helpful but should not replace hands-on knowledge. Remember, the absence of gills does not guarantee edibility—some of the deadliest mushrooms in the world lack gills. When in doubt, leave it out. Your curiosity about mushrooms should never outweigh the importance of your safety.

Identifying Yard Mushrooms: Are Your White Mushrooms Safe to Eat?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Edibility Testing Methods: Safe practices for determining if a non-gilled mushroom is edible

Not all mushrooms without gills are edible, and assuming so can lead to dangerous consequences. While some non-gilled mushrooms like puffballs and chanterelles are culinary delights, others, such as the deadly Amanita species, can be lethal. This highlights the critical need for reliable edibility testing methods when encountering unfamiliar fungi.

Relying solely on visual identification is risky, as many toxic and edible species resemble each other closely. Spore color, a common identification tool, is less useful for non-gilled mushrooms, further complicating matters. Therefore, a multi-faceted approach is essential for safe foraging.

The Spore Print Test: A Crucial First Step

One fundamental method is the spore print test. This involves placing the cap of a mature mushroom, gills downward, on a piece of white paper or glass for several hours. The spores released will create a colored deposit, which can be compared to known spore colors of edible and poisonous species. While not definitive, it provides valuable initial information. For example, a white spore print is common in many edible boletes, while a green spore print is characteristic of the poisonous Amanita phalloides.

Remember, this test only works for mushrooms with gills or pore structures. Non-gilled mushrooms like puffballs release spores through a different mechanism, rendering this method ineffective.

Chemical Tests: A Cautious Approach

Certain chemical reagents can react with specific mushroom compounds, producing color changes that may indicate toxicity. For instance, applying a drop of potassium hydroxide (KOH) to the mushroom's flesh can cause a color change in some Amanita species, signaling the presence of amatoxins, potent liver toxins. However, these tests are not foolproof and require careful interpretation. False negatives are possible, and some reactions can be ambiguous. Moreover, handling strong chemicals requires caution and proper protective gear.

This method should only be attempted by experienced foragers with a thorough understanding of mushroom chemistry and safety protocols.

The Taste Test: A Dangerous Myth

A persistent but dangerous myth suggests that tasting a small amount of a mushroom and waiting for adverse reactions can determine edibility. This is extremely risky, as many toxic mushrooms have delayed onset symptoms, and even a tiny amount can be fatal. Never rely on taste as a testing method.

The Ultimate Safeguard: Expert Consultation

The most reliable method for determining edibility is consulting with a qualified mycologist or experienced forager. They possess the knowledge and skills to accurately identify mushrooms based on a combination of morphological characteristics, habitat, and microscopic features. Many regions have mushroom identification groups or clubs that offer guidance and organize foraging expeditions.

When in doubt, always err on the side of caution and avoid consuming any mushroom unless its edibility is confirmed by a trusted expert. Remember, the consequences of misidentification can be severe.

Are Lobster Mushrooms Edible? A Guide to Safe Foraging and Cooking

You may want to see also

Ecological Roles of Non-Gilled Mushrooms: Their importance in ecosystems beyond human consumption

Non-gilled mushrooms, often overshadowed by their gill-bearing counterparts, play critical ecological roles that sustain forest health and biodiversity. Unlike the familiar button mushrooms or chanterelles, these fungi—such as puffballs, coral fungi, and bracket fungi—lack gills but excel in decomposing wood, recycling nutrients, and forming symbiotic relationships with plants. Their mycelial networks act as underground highways, transferring nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus between soil and vegetation, ensuring forest ecosystems remain fertile and resilient. Without these unsung heroes, forests would struggle to regenerate, and nutrient cycles would stall, highlighting their importance far beyond their edibility.

Consider the bracket fungi, often seen as shelf-like structures on decaying trees. While many are inedible or too tough for human consumption, they are nature’s primary wood decomposers. A single bracket fungus can break down cellulose and lignin—compounds that most organisms cannot digest—releasing carbon and minerals back into the soil. This process not only nourishes surrounding plants but also creates microhabitats for insects, mosses, and lichens. For instance, the turkey tail fungus (*Trametes versicolor*) is a powerhouse decomposer and has even been studied for its medicinal properties, showcasing how ecological function can intersect with human benefit, though not through edibility.

Instructively, non-gilled mushrooms also serve as keystone species in mycorrhizal networks, particularly those in the Boletaceae family. These fungi form symbiotic partnerships with tree roots, enhancing water and nutrient uptake for their hosts. In exchange, the trees provide carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis. This mutualism is especially vital for young trees in nutrient-poor soils, where up to 80% of a tree’s nutrient needs can be supplied by its fungal partners. Gardeners and forest managers can mimic this by inoculating soil with mycorrhizal fungi to improve plant health, though it’s crucial to match the fungus to the plant species for optimal results.

Persuasively, the ecological value of non-gilled mushrooms extends to their role in carbon sequestration. As decomposers and symbionts, these fungi store carbon in their mycelial networks and in the soil, mitigating climate change. For example, the honey mushroom (*Armillaria*) forms some of the largest living organisms on Earth, with underground networks spanning acres and storing tons of carbon. While its edibility is limited and often discouraged due to potential toxicity, its ecological impact is undeniable. Protecting these fungi means safeguarding carbon sinks and preserving the stability of forest ecosystems.

Comparatively, while gilled mushrooms often dominate culinary discussions, non-gilled species like morels and truffles are prized for their flavor, yet their ecological roles are equally fascinating. Truffles, for instance, rely on animals for spore dispersal, as their scent attracts mammals that dig them up and spread their spores. This co-evolutionary relationship underscores how non-gilled mushrooms shape ecosystems by fostering interactions between species. Even inedible varieties, like the stinkhorn fungi, contribute by attracting flies for spore dispersal, demonstrating that ecological importance transcends human utility.

In conclusion, non-gilled mushrooms are ecological linchpins, driving nutrient cycling, supporting plant growth, and storing carbon. Their roles in decomposition, symbiosis, and habitat creation highlight the interconnectedness of forest ecosystems. While not all are edible—and many should be avoided due to toxicity or toughness—their value lies in their function, not their flavor. Understanding and protecting these fungi ensures healthier forests and a more sustainable planet, reminding us that nature’s most vital work often goes unnoticed.

Is Turkey Tail Mushroom Edible? Benefits, Risks, and Safe Consumption Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all mushrooms without gills are edible. While some non-gilled mushrooms like chanterelles and morels are safe to eat, others such as the poisonous Amanita species lack gills but are highly toxic. Always verify edibility before consuming.

Edible non-gilled mushrooms often have distinct features like a porous underside (e.g., boletes), a club-like shape (e.g., coral mushrooms), or a smooth cap. However, proper identification requires knowledge of specific species, their habitats, and potential look-alikes.

Many mushrooms with pores, such as boletes, are edible, but not all. Some poisonous species, like the Devil’s Bolete, also have pores. Always cross-reference with reliable guides or consult an expert to avoid toxic varieties.