Spore-bearing plants, also known as sporophytes, are a diverse group of plants that reproduce through spores rather than seeds. These plants include ferns, mosses, liverworts, and horsetails, which are collectively referred to as non-vascular or vascular plants depending on their structure. Ferns, for example, are vascular plants with true roots, stems, and leaves, while mosses and liverworts lack these specialized tissues. Horsetails, another type of vascular spore-bearing plant, are characterized by their jointed, hollow stems and cone-like structures that produce spores. These plants thrive in moist environments and play a crucial role in ecosystems by contributing to soil stability and providing habitats for various organisms. Understanding spore-bearing plants offers valuable insights into the evolution and diversity of plant life on Earth.

What You'll Learn

- Ferns: Vascular plants with feathery fronds, reproducing via spores, thriving in moist environments

- Mosses: Small, non-vascular plants forming dense mats, releasing spores for reproduction

- Horsetails: Reed-like plants with jointed stems, producing spores in cone-like structures

- Clubmosses: Low-growing plants resembling moss, bearing spores in club-shaped structures

- Liverworts: Flat or thalloid plants, reproducing via spores, often found in damp areas

Ferns: Vascular plants with feathery fronds, reproducing via spores, thriving in moist environments

Ferns, with their delicate, feathery fronds, are a quintessential example of spore-bearing plants that have thrived on Earth for over 360 million years. Unlike flowering plants, ferns reproduce through spores, tiny, single-celled structures that develop into new plants under the right conditions. This ancient method of reproduction allows ferns to colonize diverse habitats, from tropical rainforests to temperate woodlands, as long as moisture is abundant. Their vascular system, a network of tissues for water and nutrient transport, supports their often large and intricately divided fronds, making them both structurally and visually distinctive.

To cultivate ferns successfully, focus on replicating their natural, moist environments. They prefer indirect light, as direct sunlight can scorch their fronds. Water consistently to keep the soil damp but not waterlogged, and consider placing a tray of water with pebbles beneath the pot to increase humidity. Misting the fronds occasionally can also mimic the moisture-rich air they thrive in. For indoor ferns, varieties like the Boston fern (*Nephrolepis exaltata*) or maidenhair fern (*Adiantum*) are excellent choices due to their adaptability to home conditions.

One of the most fascinating aspects of ferns is their life cycle, which alternates between a sporophyte (the plant we see) and a gametophyte (a small, heart-shaped structure). Spores released from the underside of mature fronds grow into gametophytes, which then produce eggs and sperm. This dual-phase life cycle is a hallmark of non-seed plants and highlights the evolutionary significance of ferns. Understanding this process can deepen appreciation for their resilience and adaptability, making them a rewarding subject for both gardeners and botanists.

For those looking to incorporate ferns into landscaping, consider their role in creating lush, shaded areas. They excel as ground cover, in rock gardens, or as accents in woodland settings. Pair them with other moisture-loving plants like hostas or astilbes for a cohesive, naturalistic look. Avoid planting ferns in dry, sunny spots, as they will struggle to survive without consistent moisture. With proper care, ferns can transform any space into a verdant, tranquil retreat, showcasing the beauty of spore-bearing plants in action.

Are Spore-Grown Plants Harmful? Unveiling the Truth About Their Safety

You may want to see also

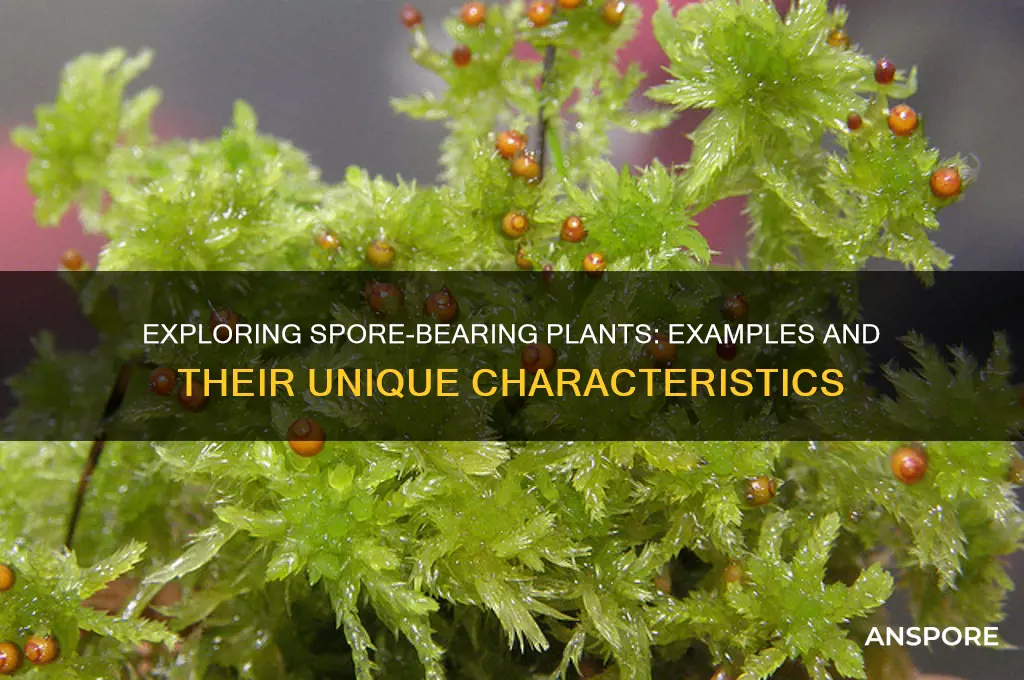

Mosses: Small, non-vascular plants forming dense mats, releasing spores for reproduction

Mosses, often overlooked in the plant kingdom, are a fascinating example of spore-bearing plants that thrive in damp, shaded environments. Unlike their vascular counterparts, mosses lack true roots, stems, and leaves, yet they form dense, lush mats that carpet forest floors, rock surfaces, and even urban walls. These mats are not just aesthetically pleasing; they play a crucial role in ecosystems by retaining moisture, preventing soil erosion, and providing habitat for microscopic organisms. The absence of vascular tissue means mosses rely on diffusion for water and nutrient transport, which confines them to moist habitats but also allows them to survive in niches where larger plants cannot.

Reproduction in mosses is a delicate, two-stage process that alternates between a gametophyte (sexually reproducing) and sporophyte (spore-producing) generation. The gametophyte, the more prominent and long-lived stage, produces gametes that, when fertilized, grow into the sporophyte. This sporophyte, often seen as a slender stalk rising from the moss mat, releases spores into the wind. These spores, lightweight and resilient, can travel great distances before settling in suitable environments to grow into new gametophytes. This reproductive strategy ensures mosses can colonize new areas efficiently, even in fragmented habitats.

For gardeners and enthusiasts, cultivating mosses can be a rewarding endeavor, particularly in shaded, humid areas where traditional plants struggle. To encourage moss growth, start by preparing a substrate of soil mixed with sand or clay, ensuring it remains consistently moist. Avoid direct sunlight, as mosses prefer indirect light. For a quicker establishment, blend healthy moss with buttermilk or yogurt and water to create a slurry, then spread it over the desired area. This method, known as "moss milkshakes," promotes adhesion and provides nutrients for initial growth. Patience is key, as mosses grow slowly but form a stable, low-maintenance ground cover once established.

Comparatively, mosses offer unique advantages over other spore-bearing plants like ferns or liverworts. Their ability to thrive in low-nutrient environments and tolerate extreme conditions, such as freezing temperatures or prolonged drought (by entering a dormant state), makes them resilient pioneers in ecological restoration projects. Additionally, mosses are bioindicators, sensitive to air quality and pollution levels, making them valuable tools for environmental monitoring. Their simplicity belies their ecological significance, serving as a reminder that even the smallest plants can have a profound impact on their surroundings.

In conclusion, mosses exemplify the adaptability and efficiency of spore-bearing plants. Their non-vascular structure, combined with a dual-stage life cycle, allows them to flourish in niches inaccessible to more complex flora. Whether appreciated for their ecological roles, cultivated for aesthetic purposes, or studied for their environmental sensitivity, mosses deserve recognition as vital contributors to biodiversity. By understanding and preserving these diminutive plants, we can better appreciate the intricate web of life they support.

Mastering Penis Envy Spore Prints: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Horsetails: Reed-like plants with jointed stems, producing spores in cone-like structures

Horsetails, scientifically known as *Equisetum*, are living fossils that have thrived on Earth for over 300 million years. These reed-like plants are instantly recognizable by their jointed, hollow stems, which resemble bamboo but are far more ancient. Unlike flowering plants, horsetails reproduce via spores housed in cone-like structures at the tips of their branches. This primitive method of reproduction links them to the earliest land plants, making them a fascinating subject for botanists and gardeners alike.

To cultivate horsetails, start by selecting a damp, shady location, as they thrive in moist soil. Plant rhizomes in spring, spacing them 12–18 inches apart to prevent aggressive spreading. While horsetails are hardy (USDA zones 3–11), they require consistent moisture, so water regularly during dry periods. A cautionary note: their rhizomes can be invasive, so consider planting them in containers or areas where their spread can be controlled. For those interested in their medicinal properties, the young shoots are rich in silica and can be harvested in early spring, dried, and steeped in tea to support bone and nail health.

Comparatively, horsetails stand apart from other spore-bearing plants like ferns and mosses. While ferns produce spores on the undersides of fronds, horsetails’ cone-like structures are more akin to primitive seed plants. Their jointed stems, a result of distinct nodes and internodes, provide structural support and allow for efficient water transport. This unique anatomy has enabled horsetails to survive mass extinctions, earning them the title of "living fossils." Their resilience makes them a valuable addition to wetland restoration projects, where they stabilize soil and filter water.

For enthusiasts looking to incorporate horsetails into landscaping, their vertical growth and vibrant green color make them excellent accents in water gardens or rain gardens. Pair them with irises or cattails for a naturalistic look. However, avoid planting them near lawns or delicate perennials, as their rhizomes can outcompete neighboring plants. If you’re experimenting with spore propagation, harvest the cones in late summer, dry them in a paper bag, and scatter the spores over prepared soil in early spring. Patience is key, as spore germination can take several weeks.

In conclusion, horsetails are not just relics of the past but versatile, dynamic plants with practical applications today. Their distinctive jointed stems and spore-producing cones offer both aesthetic appeal and ecological benefits. Whether you’re a gardener, herbalist, or simply curious about ancient plant life, horsetails provide a unique opportunity to connect with Earth’s botanical history while enhancing modern landscapes. Just remember to manage their growth thoughtfully to avoid unintended spread.

Do Algae Have Spores? Unveiling the Truth About Algal Reproduction

You may want to see also

Clubmosses: Low-growing plants resembling moss, bearing spores in club-shaped structures

Clubmosses, often mistaken for true mosses due to their low-growing, carpet-like appearance, are a distinct group of spore-bearing plants with a unique reproductive strategy. Unlike mosses, which belong to the bryophyte family, clubmosses are part of the division Lycopodiophyta, an ancient lineage dating back to the Carboniferous period. Their most striking feature is the club-shaped structures, called strobili, where spores develop and are released. These strobili are not just a curiosity—they are a key adaptation for survival in diverse habitats, from forests to bogs.

To identify clubmosses in the wild, look for their creeping or upright stems, typically no taller than 30 centimeters, covered in tiny, scale-like leaves. The strobili, often found at the tips of branches, range in color from green to yellowish-brown, depending on the species and maturity. For example, *Lycopodium clavatum*, commonly known as wolf’s-foot clubmoss, produces upright strobili that resemble tiny clubs, while *Huperzia lucidula*, or shining firmoss, has more compact, cone-like structures. Observing these details can help distinguish clubmosses from similar-looking plants like ferns or mosses.

One practical aspect of clubmosses is their historical and modern uses. In traditional medicine, extracts from *Lycopodium* species have been used for treating conditions like urinary tract infections and skin ailments, though scientific evidence supporting these uses is limited. More notably, clubmoss spores were once used as a flash powder in early photography due to their highly flammable nature. Today, they are occasionally used in special effects for their explosive properties. However, handling spores requires caution, as inhaling them can irritate the respiratory system.

For gardeners or enthusiasts interested in cultivating clubmosses, these plants thrive in moist, shaded environments with well-draining, acidic soil. They can be propagated by dividing established clumps or by sowing spores, though the latter requires patience, as germination can be slow and unpredictable. Avoid overwatering, as clubmosses are susceptible to root rot. Pairing them with ferns or other shade-loving plants in a woodland garden can create a prehistoric ambiance, highlighting their evolutionary significance.

In conclusion, clubmosses are more than just moss look-alikes—they are living fossils with fascinating biology and practical applications. Their spore-bearing strobili, low-growing habit, and resilience make them a unique addition to both natural ecosystems and cultivated gardens. Whether observed in the wild or grown at home, clubmosses offer a glimpse into the diversity of spore-bearing plants and their enduring role in the natural world.

Infusing Standing Oak Trees with Truffle Spores: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Liverworts: Flat or thalloid plants, reproducing via spores, often found in damp areas

Liverworts, often overlooked in the plant kingdom, are a fascinating group of spore-bearing organisms that thrive in damp, shaded environments. These flat or thalloid plants, named for their liver-shaped appearance in some species, are among the simplest land plants. Unlike more complex plants, liverworts lack true roots, stems, and leaves, yet they play a crucial role in ecosystems by stabilizing soil and retaining moisture. Their reproductive strategy revolves around spores, which are dispersed to colonize new areas, making them a prime example of primitive plant adaptation.

To identify liverworts, look for their distinctive structure: a thallus (a flat, undifferentiated body) or small, leaf-like structures arranged in a forked pattern. They are commonly found in moist, cool habitats such as forest floors, rock crevices, and stream banks. For gardeners or enthusiasts, creating a damp, shaded microhabitat can encourage liverwort growth. A practical tip is to mist the area regularly to maintain humidity, as these plants are highly sensitive to drying out. Avoid overwatering, as standing water can lead to rot.

From an ecological perspective, liverworts serve as indicators of environmental health. Their presence often signifies clean air and water, as they are intolerant of pollution. For conservationists, monitoring liverwort populations can provide insights into habitat quality. Additionally, their ability to reproduce via spores makes them resilient in the face of disturbance. However, habitat destruction and climate change pose significant threats, underscoring the need for protective measures.

For those interested in studying liverworts, a magnifying glass or microscope is essential to observe their intricate structures, such as gemmae cups (small, spore-like bodies) and rhizoids (root-like anchoring structures). A simple experiment involves collecting liverwort samples, placing them in a damp container, and observing spore dispersal under controlled conditions. This hands-on approach not only deepens understanding but also highlights the plant’s unique reproductive mechanisms.

In conclusion, liverworts exemplify the diversity of spore-bearing plants, offering both ecological and scientific value. Their flat or thalloid forms, coupled with their reliance on spores for reproduction, make them a distinct and adaptable group. By appreciating and protecting these plants, we contribute to the preservation of biodiversity and the delicate balance of damp ecosystems. Whether you’re a gardener, scientist, or nature enthusiast, liverworts provide a window into the resilience and simplicity of early plant life.

Are Mold Spores Always Present on Wood? Uncovering the Truth

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Examples of spore-bearing plants include ferns, mosses, liverworts, and horsetails.

No, not all spore-bearing plants are vascular plants. Mosses and liverworts are non-vascular spore-bearing plants, while ferns and horsetails are vascular.

No, spore-bearing plants do not produce flowers or seeds. They reproduce through spores, which are tiny, single-celled structures.

Spore-bearing plants are commonly found in moist, shaded environments such as forests, wetlands, and along riverbanks, as they require water for spore dispersal and reproduction.