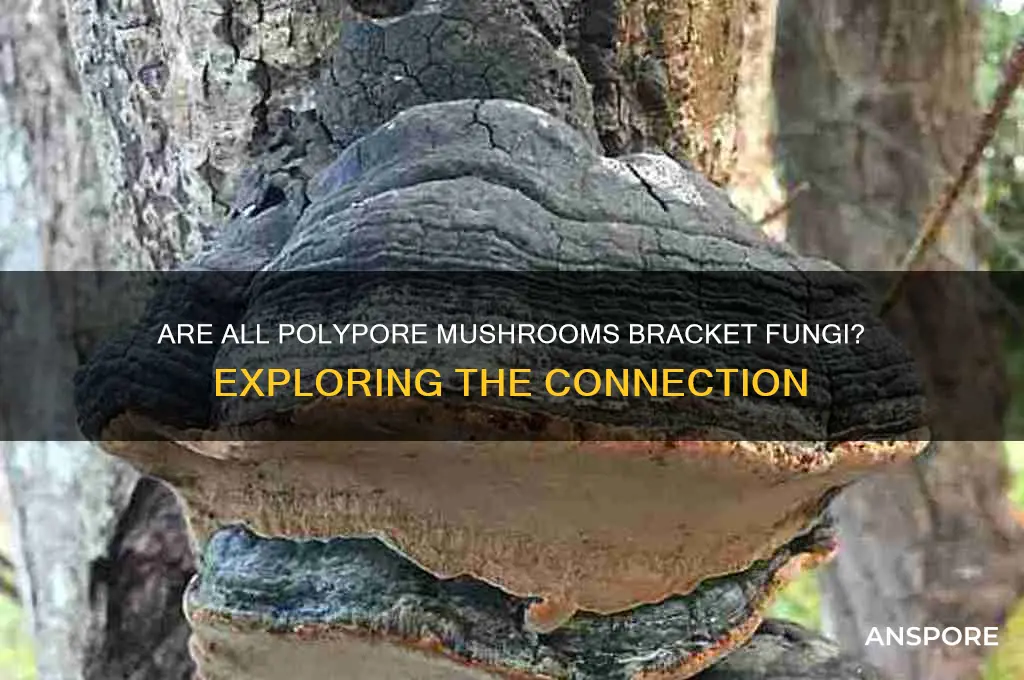

Polypore mushrooms are a diverse group of fungi known for their distinctive pore-like structures on the underside of their fruiting bodies, which release spores. Among these, bracket fungi are a common and well-recognized subset, characterized by their shelf-like or bracket-shaped growth on trees or wood. While all bracket fungi are polypores, not all polypore mushrooms are bracket fungi. Polypores encompass a broader range of species, some of which may grow in different forms, such as crust-like or even terrestrial structures, rather than the typical bracket shape. This distinction highlights the diversity within the polypore group and the importance of understanding their varied growth habits and ecological roles.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Not all polypore mushrooms are bracket fungi, but all bracket fungi are polypores. |

| Polypore Mushrooms | Mushrooms with pores on the underside of their caps, belonging to the order Polyporales. |

| Bracket Fungi | A subset of polypore mushrooms that form shelf-like or bracket-shaped fruiting bodies, typically growing on wood. |

| Growth Form | Polypores can grow in various forms (e.g., caps, brackets, crusts), while bracket fungi specifically form bracket-like structures. |

| Habitat | Both are primarily saprotrophic or parasitic on wood, but polypores can also grow on soil or other substrates. |

| Examples | Polypore: Trametes versicolor (Turkey Tail); Bracket Fungus: Ganoderma applanatum (Artist's Conk). |

| Key Distinction | Bracket fungi are distinguished by their woody, shelf-like appearance, whereas polypores encompass a broader range of forms. |

| Ecological Role | Both play crucial roles in wood decomposition and nutrient cycling in ecosystems. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Bracket Fungi Definition: Understanding what bracket fungi are and their key characteristics

- Polypore Identification: How to identify polypore mushrooms based on their features

- Bracket vs. Polypore: Key differences and similarities between bracket fungi and polypores

- Ecology of Polypores: The ecological roles and habitats of polypore mushrooms

- Are All Polypores Bracket Fungi: Clarifying if all polypore mushrooms are classified as bracket fungi?

Bracket Fungi Definition: Understanding what bracket fungi are and their key characteristics

Bracket fungi, also known as shelf fungi or polypores, are a distinctive group of fungi characterized by their woody, shelf-like fruiting bodies that grow on trees or wooden structures. These fungi are primarily saprobic, meaning they decompose dead or decaying wood, playing a crucial role in nutrient cycling within ecosystems. The term "bracket" refers to their flat, bracket-shaped appearance, which often resembles a shelf attached to the substrate. While not all bracket fungi are polypores, the majority belong to the order Polyporales, a diverse group within the Basidiomycota division. Understanding bracket fungi requires recognizing their key characteristics, which set them apart from other fungal types.

One of the defining features of bracket fungi is their tough, leathery, or woody texture, which is a result of their role in breaking down lignin and cellulose in wood. Unlike mushrooms with gills or pores, bracket fungi typically have pores on the underside of their fruiting bodies, through which they release spores. These pores are often arranged in a tubular or maze-like structure, giving them the name "polypores," meaning "many pores." The presence of pores is a critical characteristic for identification, though some bracket fungi may have unique spore-bearing structures, such as teeth or ridges, depending on the species.

Bracket fungi are perennial, meaning their fruiting bodies can persist for multiple years, growing larger with each season. This longevity distinguishes them from annual mushrooms, which typically decay after a single season. Their colors vary widely, ranging from earthy browns and grays to vibrant hues of red, orange, or green, often depending on the species and environmental conditions. The upper surface of the bracket is usually zoned or patterned, providing additional visual cues for identification.

Another key characteristic of bracket fungi is their ecological role as decomposers. They are primarily found on dead or dying trees, where they break down wood into simpler compounds, returning nutrients to the soil. While this process is beneficial for forest ecosystems, bracket fungi can also be detrimental to living trees or wooden structures, causing a type of decay known as white rot or brown rot. This dual nature highlights their importance in both natural and human-altered environments.

In summary, bracket fungi are defined by their shelf-like, woody fruiting bodies, porous undersides, and role as wood decomposers. While most bracket fungi are polypores, not all polypores are bracket fungi, as some may have different growth forms. Their perennial nature, varied coloration, and ecological significance make them a fascinating and essential group of fungi to study. Understanding these characteristics is crucial for identifying bracket fungi and appreciating their role in the natural world.

Hillbilly Mushrooms: A Forager's Delight

You may want to see also

Polypore Identification: How to identify polypore mushrooms based on their features

Polypore mushrooms, often referred to as bracket fungi, are a fascinating group of fungi known for their distinctive woody or leathery fruiting bodies that typically grow on trees or wood. While not all polypore mushrooms are bracket fungi, the majority of them fall into this category due to their shelf-like or bracket-shaped appearance. Identifying polypores involves examining specific features such as their growth habit, texture, pore structure, color, and ecological context. Understanding these characteristics is essential for accurate identification and distinguishing them from other fungi.

One of the key features for polypore identification is their growth habit. Polypores are primarily saprobic or parasitic, meaning they grow on dead or decaying wood, or occasionally on living trees. Their fruiting bodies are typically perennial, persisting for multiple years, and have a tough, woody texture. Unlike gilled mushrooms, polypores lack gills and instead have pores or tubes on the underside of their caps. These pores are a defining characteristic and can vary in size, shape, and color, making them a crucial element in identification. Observing whether the fungus grows as a bracket (shelf-like) or in a more resupinate (crust-like) form is also important, as this distinguishes them from other fungal groups.

The texture and consistency of polypores are another critical aspect of identification. Most polypores have a hard, woody, or leathery texture when mature, though some may be softer or more flexible when young. This toughness is due to the presence of thick cell walls and often correlates with their longevity. Breaking or cutting a small piece of the fruiting body can reveal its internal structure, such as the presence of layers or zones, which can aid in identification. For example, some polypores have a distinct margin or edge that is softer or more pliable than the rest of the cap.

The pore structure is perhaps the most distinctive feature of polypores. These pores are the openings of the tubes where spores are produced. Pore size, shape, and arrangement are key identification traits. Pores can be round, angular, or elongated, and their size can range from tiny to large. The color of the pores and any changes they undergo with age or when bruised can also be diagnostic. For instance, some polypores have white pores that turn brown when touched, while others have consistent coloration. Examining the tubes beneath the pores can also provide valuable information, such as their depth and color.

Color and overall appearance are additional important features for identifying polypores. While some polypores are uniformly colored, others exhibit striking patterns, zones, or contrasts between the cap, pores, and margin. Colors can range from white and cream to various shades of brown, red, yellow, green, or even blue. Environmental factors such as sunlight exposure or moisture can influence coloration, so it’s important to consider these when identifying specimens. Additionally, noting the presence of any unusual features, such as a velvety cap surface or a distinct odor, can further aid in identification.

Finally, ecological context plays a significant role in polypore identification. Observing the substrate on which the polypore is growing—whether it’s hardwood, softwood, or a specific tree species—can narrow down the possibilities. Some polypores are highly specific to certain hosts, while others are more generalists. Noting the habitat, such as whether the fungus is found in a forest, on a fallen log, or on a living tree, can also provide valuable clues. Combining these ecological observations with the physical features of the fungus allows for a more accurate and comprehensive identification of polypore mushrooms.

Magic Mushroom Decriminalization: Where Are We Now?

You may want to see also

Bracket vs. Polypore: Key differences and similarities between bracket fungi and polypores

Bracket fungi and polypores are terms often used interchangeably, but they are not entirely synonymous. While all bracket fungi are polypores, not all polypores are bracket fungi. The primary distinction lies in their growth form and habitat. Bracket fungi, also known as shelf fungi, typically grow as flat, bracket-like structures projecting from wood, often trees or fallen logs. These fungi are characterized by their tough, woody texture and their role as decomposers of lignin-rich substrates. Polypores, on the other hand, are a broader group of fungi identified by their pore-like structures on the underside of the fruiting body, which release spores. This means that while bracket fungi always exhibit a bracket-like shape, polypores can take various forms, including brackets, but also crusts, caps, or other structures, as long as they have pores.

#### Structural and Morphological Similarities

Both bracket fungi and polypores share key morphological features due to their classification within the polypores group. The most notable similarity is the presence of pores on the underside of their fruiting bodies, which are used for spore dispersal. These pores are a defining characteristic of polypores and are present in all bracket fungi since they fall under this category. Additionally, both types of fungi typically have a tough, resilient texture due to the presence of lignin-degrading enzymes, which allows them to break down wood efficiently. This shared trait makes them important decomposers in forest ecosystems, contributing to nutrient cycling and wood decomposition.

#### Habitat and Ecological Roles

Bracket fungi and polypores are predominantly found in woody environments, where they play crucial roles in decomposition. Bracket fungi are especially associated with trees, often growing directly on trunks or branches, while polypores can be found on a wider range of substrates, including soil, decaying wood, and even living trees. Both groups are saprotrophic, meaning they obtain nutrients by breaking down dead organic matter, particularly wood. However, some polypores can also be parasitic or form mutualistic relationships with plants, a behavior less commonly observed in bracket fungi. This ecological versatility highlights the broader scope of polypores compared to the more specialized bracket fungi.

#### Taxonomic Classification and Diversity

Taxonomically, both bracket fungi and polypores belong to the class Agaricomycetes and are primarily found in the order Polyporales. However, the term "polypore" encompasses a much wider range of species across multiple families, whereas bracket fungi are more narrowly defined by their growth form. The diversity within polypores is vast, with thousands of species exhibiting various shapes, colors, and ecological roles. Bracket fungi, while diverse in their own right, are a subset of this larger group, distinguished primarily by their bracket-like appearance. This taxonomic relationship underscores the hierarchical nature of fungal classification, where bracket fungi are a specialized form within the broader polypore category.

#### Practical Identification and Uses

For practical identification, the key feature to distinguish bracket fungi from other polypores is their growth form. If the fungus grows as a shelf-like structure attached to wood, it is likely a bracket fungus. However, all such fungi will have pores, confirming their classification as polypores. Both groups have been used in traditional medicine and as sources of bioactive compounds due to their unique chemical compositions. For example, the tough texture of bracket fungi makes them less palatable but valuable for their medicinal properties, while the broader diversity of polypores offers a wider range of potential applications. Understanding these differences and similarities is essential for accurate identification, ecological study, and practical use of these fascinating fungi.

Mushrooms: Are They a Psychoactive Drug?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$84.61

Ecology of Polypores: The ecological roles and habitats of polypore mushrooms

Polypores, a diverse group of fungi, play critical ecological roles in forest ecosystems, primarily as decomposers and recyclers of nutrients. These mushrooms are characterized by their porous undersides, which release spores, and their woody, bracket-like structures that often grow on trees or fallen wood. While not all polypore mushrooms are bracket fungi, many of the most recognizable polypores, such as the turkey tail (*Trametes versicolor*) and artist's conk (*Ganoderma applanatum*), exhibit this bracket-like form. Their ability to break down lignin and cellulose in dead or decaying wood makes them essential for nutrient cycling, returning vital elements like carbon and nitrogen to the soil.

The habitats of polypores are closely tied to their ecological functions. They are predominantly found in temperate and tropical forests, where they colonize both standing and fallen trees. Polypores are pioneer decomposers, often the first fungi to invade dead wood, creating pathways for other organisms to follow. This process, known as white rot or brown rot, depending on the species, softens the wood and accelerates its decomposition. In doing so, polypores contribute to the creation of microhabitats for insects, bacteria, and other fungi, fostering biodiversity within forest ecosystems.

Beyond decomposition, polypores also engage in symbiotic relationships with living trees. Some species, like the birch polypore (*Piptoporus betulinus*), form mutualistic associations with their hosts, aiding in nutrient uptake or providing protection against pathogens. However, others can act as weak parasites, slowly weakening trees over time. This dual role highlights the complexity of polypore ecology and their impact on forest health. Their presence often indicates the age and maturity of a forest, as they thrive in environments with abundant dead wood, a hallmark of old-growth ecosystems.

Polypores are also integral to soil formation and structure. As they decompose wood, they release organic matter that enriches the soil, enhancing its fertility and water-holding capacity. This process is particularly important in nutrient-poor environments, where polypores act as key agents of nutrient mobilization. Additionally, their bracket-like fruiting bodies provide shelter and food for various invertebrates, further embedding them in the forest food web.

In terms of conservation, polypores are indicators of ecosystem health and biodiversity. Their sensitivity to habitat disturbance, pollution, and climate change makes them valuable bioindicators. For instance, the decline of certain polypore species can signal the degradation of forest ecosystems. Protecting polypore habitats, such as preserving dead wood and minimizing forest fragmentation, is crucial for maintaining their ecological functions. Understanding the ecology of polypores not only sheds light on their roles as decomposers and symbionts but also underscores their importance in sustaining forest ecosystems and the broader environment.

Psychedelics: Are LSD and Mushrooms the Same?

You may want to see also

Are All Polypores Bracket Fungi?: Clarifying if all polypore mushrooms are classified as bracket fungi

Polypores and bracket fungi are terms often used in mycology, the study of fungi, but they are not always synonymous. Polypores are a group of fungi characterized by their porous spore-bearing surface, typically found on the underside of the fruiting body. These pores release spores, which are essential for the fungus's reproduction. Bracket fungi, on the other hand, are a type of fungal growth that forms shelf-like structures, often attached to trees or wood. While many polypores do indeed form bracket-like structures, not all polypores fit this description, and not all bracket fungi are polypores. This distinction is crucial for understanding the diversity within these fungal groups.

Characteristics of Polypores

Polypores belong to the phylum Basidiomycota and are primarily saprotrophic, meaning they decompose dead organic matter, particularly wood. Their fruiting bodies can vary widely in shape, size, and color, but the defining feature is the presence of pores on the underside. These pores are formed by elongated cells called tubes, which open at the surface to release spores. Polypores can be found in various habitats, including forests, where they play a vital role in nutrient cycling by breaking down lignin and cellulose in wood. Some polypores grow in a bracket-like form, but others may be resupinate (crust-like) or even have a more complex morphology, such as those with caps and stems.

Bracket Fungi: A Specific Growth Form

Bracket fungi are characterized by their shelf-like or bracket-shaped fruiting bodies, which typically grow on wood. These structures are often tough and woody, allowing them to persist for multiple years. While many bracket fungi are polypores, some belong to other groups, such as the genus Ganoderma, which has a shiny, lacquered appearance and a double-walled spore structure. The term "bracket fungus" refers to the growth form rather than a specific taxonomic group, which means that not all bracket fungi share the same spore-bearing structure as polypores. For example, some bracket fungi have gills or other spore-bearing surfaces.

Overlap and Differences Between Polypores and Bracket Fungi

The overlap between polypores and bracket fungi lies in their common habitat and growth form. Many polypores, such as the turkey tail (*Trametes versicolor*) and the artist's conk (*Ganoderma applanatum*), form bracket-like structures on trees. However, not all polypores grow in this manner. Some, like the crust-like *Phellinus* species, are resupinate and do not form brackets. Conversely, not all bracket fungi are polypores. For instance, the sulfur shelf (*Laetiporus sulphureus*) has a bracket-like form but bears its spores on gills rather than pores. This highlights the importance of distinguishing between growth form and spore-bearing structure when classifying fungi.

In conclusion, while many polypores are indeed bracket fungi, not all polypores fit this description, and not all bracket fungi are polypores. The term "polypore" refers to the spore-bearing structure (pores), whereas "bracket fungus" describes the growth form (shelf-like structures). Understanding these distinctions is essential for accurate identification and classification. Polypores encompass a wide range of forms, including brackets, crusts, and others, while bracket fungi can belong to various taxonomic groups, not just polypores. Therefore, while there is significant overlap, the two terms are not interchangeable, and careful observation of both growth form and spore-bearing structure is necessary to classify these fungi correctly.

Matcha and Mushrooms: What's the Deal?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, all polypore mushrooms are considered bracket fungi. Polypore mushrooms are characterized by their pore-like structures on the underside of the cap, and they typically grow in a shelf-like or bracket-like form on wood.

While most polypore mushrooms grow as bracket fungi, some species may appear in different forms, such as convex caps or irregular shapes, depending on their environment. However, the majority are bracket-like.

Not necessarily. While all polypore mushrooms are bracket fungi, not all bracket fungi are polypores. Some bracket fungi belong to other groups, such as the genus *Ganoderma*, which has gills or other structures instead of pores.