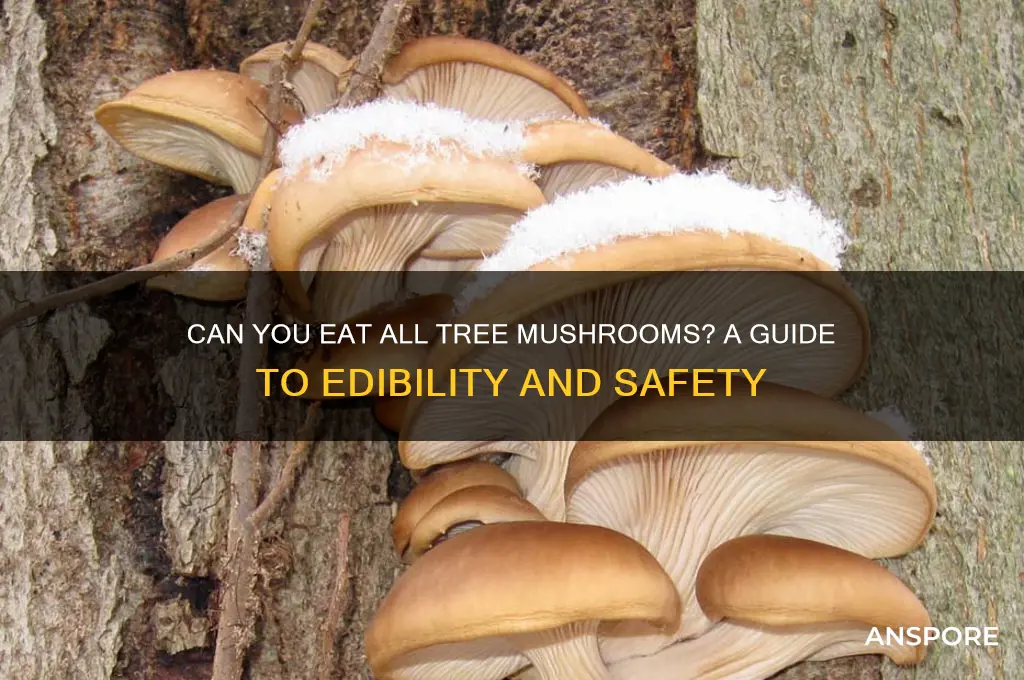

Tree mushrooms, often found growing on or around trees, are a diverse group of fungi that can range from delicious culinary treasures to toxic hazards. While some species, like the prized lion’s mane or oyster mushrooms, are safe and highly sought after for their flavor and nutritional benefits, others, such as the deadly Amanita species, can cause severe illness or even be fatal if consumed. Identifying tree mushrooms accurately is crucial, as many edible and poisonous varieties resemble each other closely. Factors like tree type, mushroom color, texture, and spore characteristics can help distinguish safe species from harmful ones, but consulting a reliable guide or expert is always recommended to avoid risks.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Are all tree mushrooms edible? | No, not all tree mushrooms are edible. Many are toxic or poisonous. |

| Edible Tree Mushrooms | Examples include Oyster mushrooms, Lion's Mane, and Chicken of the Woods. |

| Toxic Tree Mushrooms | Examples include Sulphur Shelf (false Chicken of the Woods), some species of Amanita, and Jack-O-Lantern mushrooms. |

| Key Identification Factors | Proper identification requires examining features like cap shape, gill structure, spore color, smell, and habitat. |

| Risk of Misidentification | High; many toxic mushrooms resemble edible ones, making expert knowledge or consultation essential. |

| Common Misconceptions | "Bright colors mean toxicity" is false; some edible mushrooms are brightly colored, and some toxic ones are plain. |

| Safe Foraging Practices | Always consult a field guide or expert, avoid consuming unless 100% sure, and cook mushrooms thoroughly before eating. |

| Symptoms of Poisoning | Can include gastrointestinal distress, hallucinations, organ failure, or death, depending on the species ingested. |

| Ecological Role | Tree mushrooms often play a role in decomposition or as mycorrhizal partners with trees, regardless of edibility. |

| Seasonal Availability | Varies by species; some tree mushrooms are found in spring, others in fall, depending on climate and location. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Common Edible Varieties: Identifying safe mushrooms like chanterelles, morels, and lion's mane growing on trees

- Toxic Tree Mushrooms: Recognizing poisonous species such as Amanita and Galerina found on trees

- Look-Alike Dangers: Distinguishing edible mushrooms from toxic doppelgängers to avoid misidentification risks

- Habitat and Safety: Understanding how tree type and environment affect mushroom edibility and safety

- Foraging Guidelines: Essential tips for safely harvesting and consuming tree mushrooms without risk

Common Edible Varieties: Identifying safe mushrooms like chanterelles, morels, and lion's mane growing on trees

Not all tree mushrooms are edible, and misidentification can lead to severe poisoning or even death. However, several prized varieties grow on trees and are safe to consume when properly identified. Among these, chanterelles, morels, and lion’s mane stand out for their distinct characteristics and culinary value. Recognizing these species requires attention to detail, as look-alikes can be deceptive. Foraging safely begins with understanding their unique features and habitats.

Chanterelles, often found at the base of hardwood trees like oak and beech, are prized for their fruity aroma and golden, wavy caps. Their false gills, which fork and run down the stem, are a key identifier. Unlike poisonous look-alikes such as jack-o’-lanterns, which grow in clusters and have true gills, chanterelles grow singly or in small groups. When harvesting, ensure the mushroom has a firm texture and lacks any slimy residue. Cooking enhances their flavor, and they pair well with eggs, pasta, or cream-based sauces.

Morels, another highly sought-after variety, often grow near deciduous trees like ash, elm, and poplar. Their honeycomb-like caps and hollow stems distinguish them from false morels, which have wrinkled, brain-like caps and are toxic. True morels should be cut open to confirm their hollow interior. Always cook morels thoroughly, as consuming them raw can cause digestive issues. Their earthy flavor makes them ideal for sautéing, stuffing, or incorporating into soups and sauces.

Lion’s mane mushrooms, recognizable by their cascading white spines, typically grow on dead or dying hardwood trees. Their appearance resembles a shaggy mane, earning them the nickname "pom-pom mushroom." Unlike toxic look-alikes such as the splitting tooth fungus, lion’s mane has soft, dangling spines rather than rigid, brittle ones. These mushrooms are not only edible but also valued for their potential cognitive benefits. They can be prepared like crab meat, battered and fried, or used in teas and tinctures.

When foraging for these varieties, always carry a field guide or use a reliable mushroom identification app. Avoid picking mushrooms near polluted areas or treated wood, as they can absorb toxins. Properly clean and store your harvest to preserve freshness. While chanterelles, morels, and lion’s mane are safe when correctly identified, never consume a mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity. Foraging with an experienced guide can provide hands-on learning and reduce the risk of mistakes.

Are Dead Man's Fingers Mushrooms Edible? A Safety Guide

You may want to see also

Toxic Tree Mushrooms: Recognizing poisonous species such as Amanita and Galerina found on trees

Not all tree mushrooms are edible, and misidentification can lead to severe poisoning or even death. Among the most dangerous are species from the *Amanita* and *Galerina* genera, which often grow on or near trees and resemble harmless varieties. For instance, the *Amanita phalloides*, commonly known as the Death Cap, is responsible for the majority of fatal mushroom poisonings worldwide. Its olive-green cap and white gills can easily be mistaken for edible species like the Paddy Straw mushroom, especially by inexperienced foragers.

Recognizing toxic tree mushrooms requires attention to detail. *Amanita* species often have a distinctive cup-like volva at the base of the stem, a feature absent in most edible mushrooms. *Galerina* mushrooms, on the other hand, are smaller and less showy but equally dangerous. They contain the same deadly amatoxins as *Amanita phalloides* and are frequently found on decaying wood. A key identifier for *Galerina* is their rusty-brown spore print, which can be obtained by placing the cap gills-down on paper overnight.

If you suspect ingestion of a toxic tree mushroom, immediate medical attention is critical. Symptoms of amatoxin poisoning, such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, may not appear for 6–24 hours, creating a false sense of security. However, these toxins cause severe liver and kidney damage, often leading to organ failure within 48–72 hours. Activated charcoal may be administered in the emergency room to reduce toxin absorption, but the most effective treatment is a liver transplant in severe cases.

To avoid accidental poisoning, follow these practical tips: always cross-reference multiple field guides or apps when identifying mushrooms, and never consume a mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity. Carry a spore print kit and a small knife for detailed examination. For beginners, foraging with an experienced mycologist is highly recommended. Remember, the adage "there are old foragers and bold foragers, but no old, bold foragers" holds true when dealing with toxic tree mushrooms like *Amanita* and *Galerina*.

Mushroom Gummies vs. Edibles: Which Delivers Faster Effects?

You may want to see also

Look-Alike Dangers: Distinguishing edible mushrooms from toxic doppelgängers to avoid misidentification risks

Not all tree mushrooms are edible, and misidentifying a toxic species for a safe one can have severe consequences. The forest floor is a minefield of look-alike dangers, where edible mushrooms like the oyster mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) can be easily confused with the poisonous jack-o’-lantern (*Omphalotus olearius*). Both grow on wood, both have gills, and both can appear in similar clusters, but the jack-o’-lantern’s bright orange glow and lack of a true stem are critical distinctions. Ingesting the latter can cause severe gastrointestinal distress, including vomiting and diarrhea, within 30 minutes to 2 hours. Always check for bioluminescence—a telltale sign of toxicity in this species—by crushing a small piece in the dark.

Distinguishing features go beyond color and shape. The false morel (*Gyromitra esculenta*), often mistaken for the edible true morel (*Morchella* spp.), contains gyromitrin, a toxin that converts to monomethylhydrazine in the body. Symptoms of poisoning include nausea, dizziness, and in severe cases, liver failure. To avoid this, examine the cap structure: false morels have a wrinkled, brain-like appearance, while true morels have a honeycomb texture. Additionally, boiling false morels in water for at least 15 minutes can reduce toxin levels, but this is not a foolproof method and is not recommended for novice foragers.

Texture and spore color are equally vital clues. The edible lion’s mane mushroom (*Hericium erinaceus*) has cascading spines instead of gills, while the toxic split gill (*Schizophyllum commune*) has a gill-like underside that splits when dry. Spore prints—obtained by placing the cap on paper overnight—can also differentiate species. For instance, the edible chanterelle (*Cantharellus cibarius*) produces a yellow-orange spore print, whereas its toxic look-alike, the false chanterelle (*Hygrophoropsis aurantiaca*), yields a white one. Always carry a spore print kit and a field guide when foraging.

Habitat and seasonality provide additional context. The edible chicken of the woods (*Laetiporus sulphureous*) thrives on hardwood trees in late summer, while its toxic doppelgänger, the sulfur shelf (*Laetiporus conifericola*), prefers conifers. Similarly, the edible birch bolete (*Leccinum scabrum*) appears in summer under birch trees, but the toxic red-pored bolete (*Rubroboletus eastwoodiae*) grows in similar environments. Cross-referencing these details with a trusted guide reduces misidentification risks. Never rely on folklore or single characteristics; always verify multiple traits before consuming.

Finally, when in doubt, throw it out. No meal is worth the risk of poisoning. Novice foragers should join local mycological societies or attend guided walks to learn from experts. Start with easily identifiable species like shiitake (*Lentinula edodes*) or maitake (*Grifola frondosa*) before tackling more complex look-alikes. Remember, even experienced foragers occasionally make mistakes, so treat every find with caution. The forest’s bounty is vast, but so are its dangers—respect both.

Are Fairy Ring Mushrooms Edible? A Guide to Safety and Identification

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$21.74 $24.95

$16.03 $24.99

Habitat and Safety: Understanding how tree type and environment affect mushroom edibility and safety

Tree species act as silent partners in the mushroom world, their unique chemistries influencing the fungi that grow upon them. Oak trees, for instance, often host the prized lion's mane mushroom (*Hericium erinaceus*), known for its seafood-like texture and potential cognitive benefits. Conversely, yew trees can foster toxic species like the deceptively similar-looking *Clitocybe* genus, some members of which contain deadly amatoxins. This symbiotic relationship underscores a critical rule: the identity of the host tree is a vital clue, but not a definitive answer, in assessing mushroom edibility.

Environmental factors further complicate this delicate dance. Moisture levels, sunlight exposure, and soil composition create microclimates that can alter a mushroom's chemical profile. The same species growing on the same tree type may produce varying toxin levels depending on whether it's in a damp, shaded hollow or a sun-dappled forest edge. For example, the common oyster mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) is generally safe, but specimens growing on trees treated with pesticides or near industrial areas can accumulate harmful substances, rendering them unsafe for consumption.

To navigate this complexity, foragers must adopt a multi-faceted approach. First, learn to identify not just mushrooms, but their host trees—a skill that requires cross-disciplinary knowledge of botany and mycology. Second, consider the environment: avoid collecting near roadsides, agricultural fields, or areas with known pollution. Third, when in doubt, employ a taste test with caution: touch a small piece of the mushroom to your tongue, wait 15-20 minutes, and if no burning, numbness, or discomfort occurs, proceed with a pea-sized bite, waiting 24 hours before consuming more. This method, while not foolproof, can help rule out some toxic species.

Children and pets, with their lower body weights and developing systems, are particularly vulnerable to mushroom toxins. Keep them away from all wild mushrooms, and educate them about the dangers of ingestion. For adults, the stakes are equally high: misidentification can lead to severe gastrointestinal distress, organ failure, or even death. The infamous death cap (*Amanita phalloides*), often found near oak trees, is responsible for the majority of fatal mushroom poisonings worldwide, its innocuous appearance belying its deadly payload.

In conclusion, the edibility of tree mushrooms is a nuanced interplay of biology and ecology. While certain tree-mushroom pairings may suggest safety, environmental variables can introduce unpredictability. Foraging should be approached with humility, preparation, and a commitment to ongoing learning. Carry a field guide, join local mycological societies, and when in doubt, leave it out—a mantra that could save lives. The forest's bounty is tempting, but its rules are non-negotiable.

Are All Brown-Gilled Mushrooms Safe to Eat? A Guide

You may want to see also

Foraging Guidelines: Essential tips for safely harvesting and consuming tree mushrooms without risk

Not all tree mushrooms are edible, and misidentification can lead to severe poisoning or even death. Before foraging, educate yourself on the specific species growing in your region. Field guides, local mycological clubs, and reputable online resources are invaluable tools. For instance, the lion’s mane mushroom (*Hericium erinaceus*) is a prized edible species often found on hardwood trees, while the deadly galerina (*Galerina marginata*) resembles harmless honey mushrooms and grows on wood. Always cross-reference multiple sources and, when in doubt, consult an expert.

Harvesting mushrooms safely begins with proper technique. Use a sharp knife to cut the mushroom at the base of the stem, leaving the mycelium undisturbed to encourage future growth. Avoid pulling or twisting, as this can damage the fungus and its environment. Wear gloves to protect your hands from potential irritants or allergens, and carry a mesh bag to allow spores to disperse as you walk, aiding in the mushroom’s lifecycle. Never harvest more than you can safely identify and consume, as over-foraging can deplete local ecosystems.

Once harvested, proper identification is critical. Examine key features such as cap shape, gill structure, spore color, and habitat. For example, the edible chicken of the woods (*Laetiporus sulphureus*) has bright orange, shelf-like fruiting bodies, while the toxic sulfur shelf (*Hypholoma fasciculare*) resembles it but grows in clusters and has green spores. Perform a spore print test by placing the cap gills-down on paper overnight to observe color. If unsure, discard the mushroom—consuming even a small amount of a toxic species can be dangerous.

Preparation and consumption require equal caution. Always cook wild mushrooms thoroughly, as many contain compounds that are neutralized by heat. Start with a small portion (50–100 grams) to test for allergic reactions, especially if it’s your first time consuming a particular species. Avoid pairing wild mushrooms with alcohol, as some toxins can interact adversely. Store harvested mushrooms in a breathable container (like a paper bag) in the refrigerator and consume within 2–3 days to ensure freshness and safety.

Finally, ethical foraging is as important as safety. Respect private property and obtain permission before harvesting on land that isn’t yours. Avoid areas contaminated by pollutants, such as roadsides or industrial sites, as mushrooms readily absorb toxins. Leave behind old or decaying specimens to allow them to release spores and contribute to the ecosystem. By following these guidelines, you can enjoy the rewards of foraging while minimizing risks to yourself and the environment.

Identifying Yard Mushrooms: Are Your White Mushrooms Safe to Eat?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all tree mushrooms are edible. Many tree mushrooms are toxic or inedible, and consuming them can lead to severe illness or even death. Always consult a reliable guide or expert before eating any wild mushroom.

Identifying edible tree mushrooms requires knowledge of specific characteristics, such as color, shape, gills, and spore print. Since many toxic mushrooms resemble edible ones, it’s crucial to consult a mycologist or use a trusted field guide to avoid mistakes.

Yes, some common edible tree mushrooms include the Lion’s Mane (*Hericium erinaceus*), Oyster Mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*), and Chicken of the Woods (*Laetiporus sulphureus*). However, proper identification is essential, as look-alike species can be harmful.