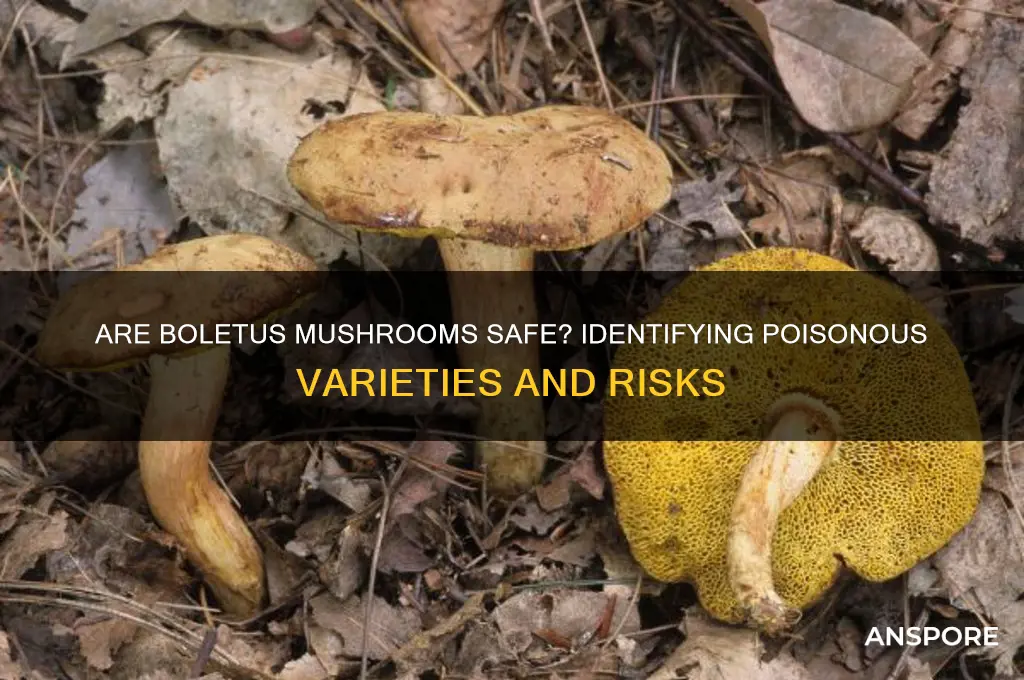

Boletus mushrooms, commonly known as porcini or cep, are highly prized in culinary traditions worldwide for their rich, nutty flavor and meaty texture. While many species in the Boletus genus are edible and considered delicacies, it is crucial to approach foraging with caution, as not all Boletus mushrooms are safe to consume. Some species, such as *Boletus satanas* and *Boletus luridiformis*, contain toxins that can cause gastrointestinal distress or other adverse reactions if ingested. Proper identification is essential, as certain poisonous Boletus species closely resemble their edible counterparts, making it imperative for foragers to be well-informed and vigilant to avoid potential risks.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Are any Boletus mushrooms poisonous? | While most Boletus species are edible, some can be toxic or cause adverse reactions. |

| Toxic Species | Examples include Boletus satanas (Devil's Boletus) and Boletus luridus (Lurid Bolete), which can cause gastrointestinal issues. |

| Mildly Toxic Species | Boletus sensibilis can cause allergic reactions in some individuals. |

| Edible Species | Many Boletus species, such as Boletus edulis (Porcini), Boletus aereus, and Boletus pinophilus, are highly prized as edible mushrooms. |

| Key Identification Features | Always identify Boletus mushrooms by their spore print, pore structure, and lack of a ring on the stem. Misidentification can lead to poisoning. |

| General Advice | Avoid consuming any wild mushroom unless positively identified by an expert. Some toxic species resemble edible ones. |

| Symptoms of Poisoning | Symptoms from toxic Boletus species can include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and in severe cases, liver damage. |

| Geographical Variation | Toxicity can vary by region, so local knowledge is crucial. |

Explore related products

$7.62 $14.95

What You'll Learn

- Deadly Boletus Species: Identify mushrooms like Boletus satanas, known for severe gastrointestinal symptoms

- Look-Alike Dangers: Toxic species mimicking edible boletus, such as Rubroboletus pulcherrimus

- Symptoms of Poisoning: Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and liver damage from toxic boletus ingestion

- Safe Identification Tips: Check pore color, bruising reactions, and habitat to avoid poisonous types

- Regional Toxic Varieties: Local boletus species that are poisonous in specific geographic areas

Deadly Boletus Species: Identify mushrooms like Boletus satanas, known for severe gastrointestinal symptoms

While many boletus mushrooms are prized for their culinary value, a few species lurk in the woods with the potential to cause severe harm. Among these, Boletus satanas, aptly named the Devil’s Bolete, stands out as a prime example of a deadly boletus species. Its striking appearance—white to pale yellow cap, stout stem, and reddish pores—might tempt foragers, but consuming even a small amount can lead to violent gastrointestinal symptoms. Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain typically manifest within 30 minutes to 2 hours after ingestion, often accompanied by cold sweats and dizziness. These symptoms can be so severe that hospitalization is frequently required, particularly for children, the elderly, or individuals with compromised immune systems.

Identifying *Boletus satanas* requires careful observation. Unlike its edible relatives, such as *Boletus edulis* (porcini), the Devil’s Bolete has a distinct blue-green bruising reaction when its flesh is damaged. Its pores, initially white, turn dull yellow to olive-green with age. Foraging without a reliable field guide or expert guidance can be perilous, as *B. satanas* often grows in similar habitats to edible boletes, such as deciduous and coniferous forests. A single misidentified mushroom can ruin a meal—or worse, endanger a life.

Comparatively, other toxic boletus species like *Boletus huronensis* and *Boletus roxanae* also cause gastrointestinal distress, but their symptoms are generally milder than those of *B. satanas*. However, the Devil’s Bolete’s toxicity is not cumulative; repeated exposure does not build tolerance. Its primary toxins remain poorly understood, but their rapid onset and intensity underscore the importance of accurate identification. Foraging groups and mycological societies often emphasize the "when in doubt, throw it out" rule, which is particularly crucial when dealing with boletus species.

To avoid accidental poisoning, follow these practical steps: First, always cut mushrooms in half lengthwise to examine their internal structure. *Boletus satanas* has a white to pale yellow flesh that bruises blue-green, while edible boletes typically do not exhibit this reaction. Second, note the spore color by placing the cap on a white surface overnight; *B. satanas* produces olive-green spores, whereas edible boletes often produce brown or yellowish spores. Third, consult multiple field guides or apps, but never rely solely on digital tools. Finally, if you suspect ingestion of a toxic boletus, seek medical attention immediately, bringing a sample of the mushroom for identification.

The takeaway is clear: while boletus mushrooms offer some of the most prized edible species, their deadly counterparts demand respect and caution. *Boletus satanas* is not just a name—it’s a warning. By mastering its identification and understanding its risks, foragers can safely enjoy the bounty of the forest without falling victim to its dangers.

Are Lawn Mushrooms Poisonous? Identifying Safe and Toxic Varieties

You may want to see also

Look-Alike Dangers: Toxic species mimicking edible boletus, such as Rubroboletus pulcherrimus

While many boletus mushrooms are prized for their culinary value, foragers must remain vigilant against toxic look-alikes. One particularly deceptive species is *Rubroboletus pulcherrimus*, often mistaken for edible boletus due to its striking red pores and robust stature. This imposter, however, contains toxins that can cause severe gastrointestinal distress, including nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, typically within 30 minutes to 2 hours of ingestion. Unlike its edible counterparts, *R. pulcherrimus* has a bitter taste and a reticulated (netted) stem, but these features are often overlooked by inexperienced foragers.

To avoid falling victim to such mimicry, foragers should employ a multi-step identification process. First, examine the pore color: edible boletus species typically have white, yellow, or olive pores, while *R. pulcherrimus* boasts bright red pores that bruise blue-green. Second, inspect the stem for reticulation—a net-like pattern absent in most edible boletus. Third, perform a taste test: a small nibble (not swallowed) of the cap can reveal bitterness, a red flag for toxicity. If in doubt, discard the mushroom entirely, as even small amounts of toxins can cause discomfort.

The danger of *R. pulcherrimus* lies not only in its toxicity but also in its geographic range, overlapping with popular foraging areas in North America. It thrives in coniferous and mixed forests, often appearing alongside edible species like *Boletus edulis* or *Boletus regius*. Foragers should be especially cautious during late summer and fall, when these species fruit concurrently. Carrying a reliable field guide or using a mushroom identification app can provide critical support, but no tool replaces hands-on knowledge and careful observation.

A comparative analysis highlights the importance of understanding subtle differences. For instance, while both *R. pulcherrimus* and *B. edulis* have stout stems, the former’s reticulation and red pores are unmistakable upon close inspection. Additionally, *R. pulcherrimus* often emits a faint, unpleasant odor when cut, contrasting with the mild scent of edible boletus. These distinctions, though minor, are lifesavers for those who prioritize accuracy over haste.

In conclusion, the allure of edible boletus mushrooms must be tempered by awareness of toxic mimics like *R. pulcherrimus*. By combining careful observation, sensory tests, and geographic knowledge, foragers can safely enjoy their harvest while avoiding the pitfalls of look-alike species. Remember: when in doubt, throw it out—no meal is worth the risk of poisoning.

Are Toadstool Mushrooms Poisonous? Unveiling the Truth Behind the Myth

You may want to see also

Symptoms of Poisoning: Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and liver damage from toxic boletus ingestion

Toxic boletus mushrooms, though less infamous than their deadly Amanita cousins, can still wreak havoc on the human body. Ingesting species like *Boletus satanas* or *Boletus luridus* often triggers a cascade of gastrointestinal symptoms within hours. Nausea strikes first, a queasy warning sign that something is amiss. This quickly escalates to vomiting and diarrhea, the body’s desperate attempt to expel the toxin. While these symptoms are uncomfortable, they’re often mistaken for food poisoning, delaying proper treatment. What sets toxic boletus poisoning apart is its potential for liver damage, a silent threat that may not manifest until days later.

The severity of symptoms depends on the species ingested and the amount consumed. A single cap of *Boletus satanas*, for instance, can cause severe distress in adults, while even smaller quantities may endanger children or pets. Vomiting and diarrhea can lead to dehydration, especially in vulnerable populations, requiring immediate rehydration with oral electrolyte solutions. Over-the-counter antiemetics may alleviate nausea, but self-medication should never replace professional medical advice. Liver damage, though rare, is the most serious complication, often requiring hospitalization and monitoring of liver enzymes like ALT and AST.

To mitigate risks, always cook boletus mushrooms thoroughly, as heat can break down some toxins. However, this method is not foolproof, particularly with species like *Boletus luridus*, whose toxins remain stable even after cooking. If symptoms appear after consumption, seek medical attention promptly. Bring a sample of the mushroom for identification, as this aids in diagnosis and treatment. Remember, early intervention can prevent long-term liver damage and ensure a full recovery.

While not all boletus mushrooms are toxic, misidentification is common, even among experienced foragers. Species like *Boletus edulis* (porcini) are prized delicacies, but their toxic look-alikes can be deceiving. Always cross-reference findings with reliable guides or consult a mycologist. When in doubt, discard the mushroom—the risk is never worth the reward. Understanding the symptoms of toxic boletus poisoning empowers foragers to act swiftly, turning a potentially dangerous situation into a manageable one.

Are All Wild Mushrooms in NC Poisonous? A Forager's Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$22.04 $29.99

Safe Identification Tips: Check pore color, bruising reactions, and habitat to avoid poisonous types

Pore color is your first clue in distinguishing safe boletus mushrooms from their toxic counterparts. Most edible boletus species, like the prized porcini (Boletus edulis), have white or cream-colored pores when young, gradually turning yellowish or greenish-brown with age. In contrast, poisonous varieties often display red, pink, or bright orange pores. For instance, the red-pored *Boletus flammans* and *Boletus rubroflammeus* are known to cause gastrointestinal distress. Always examine the pore color carefully, noting any unusual hues that deviate from the typical spectrum of edible species.

Bruising reactions are another critical indicator. When you handle a boletus mushroom, pay attention to how its flesh reacts. Edible boletus mushrooms typically bruise blue or brown when cut or damaged, a harmless chemical reaction. However, some toxic species, like *Boletus sensibilis*, turn bright red or orange upon bruising. This vivid color change is a red flag, signaling potential toxicity. Test by gently pressing the cap or stem; if it reacts with an intense, unnatural color, discard it immediately.

Habitat plays a subtle yet significant role in identification. Edible boletus mushrooms are often found in specific ecosystems, such as coniferous or deciduous forests, where they form mycorrhizal relationships with trees like oak, pine, or spruce. Poisonous species, however, may appear in less typical environments, such as disturbed soils or urban areas. For example, *Boletus satanas*, a toxic species, is sometimes found in richer, calcareous soils. Always note the surrounding vegetation and soil type when foraging, as these details can help narrow down the species and its safety.

To safely identify boletus mushrooms, combine these observations systematically. Start with pore color, then test for bruising reactions, and finally consider the habitat. For beginners, carry a reliable field guide or use a mushroom identification app for cross-referencing. Remember, even experienced foragers double-check their findings. When in doubt, leave the mushroom untouched—misidentification can have serious consequences. By mastering these specific traits, you’ll enhance your ability to distinguish safe boletus species from their poisonous look-alikes.

Wild Mushrooms and Dogs: Poisonous Risks and Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Regional Toxic Varieties: Local boletus species that are poisonous in specific geographic areas

While many Boletus mushrooms are prized for their culinary value, certain species exhibit toxicity restricted to specific geographic regions. This phenomenon underscores the importance of local knowledge in mushroom foraging. For instance, *Boletus satanas*, commonly known as the Devil’s Bolete, is widely regarded as poisonous across Europe, causing gastrointestinal distress such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. However, in some Eastern European regions, experienced foragers claim it can be safely consumed after thorough cooking, though this practice is not recommended due to inconsistent results and potential risks.

In North America, *Boletus frostii* (the Frost’s Bolete) serves as another example of regional toxicity. While generally considered edible, it has been associated with adverse reactions in certain areas, particularly when consumed raw or undercooked. Symptoms include mild gastrointestinal upset, which can be avoided by ensuring the mushroom is fully cooked. This highlights the need for regional foraging guides and consultation with local mycological experts to accurately identify and assess risk.

A more extreme case is *Boletus luridiformis*, found in parts of Europe and Asia. This species contains toxins that can cause severe gastrointestinal symptoms, including prolonged diarrhea and dehydration, particularly in children and the elderly. Unlike *B. satanas*, there is no known method to neutralize its toxins through preparation, making it a species to avoid entirely in affected regions. Dosage plays a critical role here; even small quantities can lead to discomfort, emphasizing the importance of precise identification.

Practical tips for foragers include documenting the exact location of collected specimens and cross-referencing with regional toxicity databases. For example, in the Pacific Northwest of the United States, certain Boletus species may resemble their edible counterparts but contain toxins not present in other regions. Always err on the side of caution: if a species’ edibility is uncertain or known to be regionally toxic, discard it. Carrying a local field guide and a small notebook to record findings can be lifesaving tools for any forager navigating these geographic nuances.

Are Yard Mushrooms Poisonous to Dogs? Essential Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all boletus mushrooms are safe. While many species in the *Boletus* genus are edible, some can be poisonous or cause adverse reactions. Always identify with certainty before consuming.

Look for key indicators like a reddish or dark bruising when cut, a bitter taste, or an unpleasant odor. Some toxic species, like *Boletus satanas*, have distinctive features, but proper identification is crucial.

While no *Boletus* species are known to be deadly, some can cause severe gastrointestinal distress. For example, *Boletus huronensis* and *Boletus roxanae* are known to be toxic.

Blue bruising is common in many edible boletus species, but its absence doesn’t guarantee safety. Always cross-reference other characteristics and consult a reliable guide or expert.

No, tasting is not a reliable method to determine if a boletus mushroom is poisonous. Some toxic species can cause harm even in small amounts, and symptoms may be delayed. Always identify with certainty before consuming.