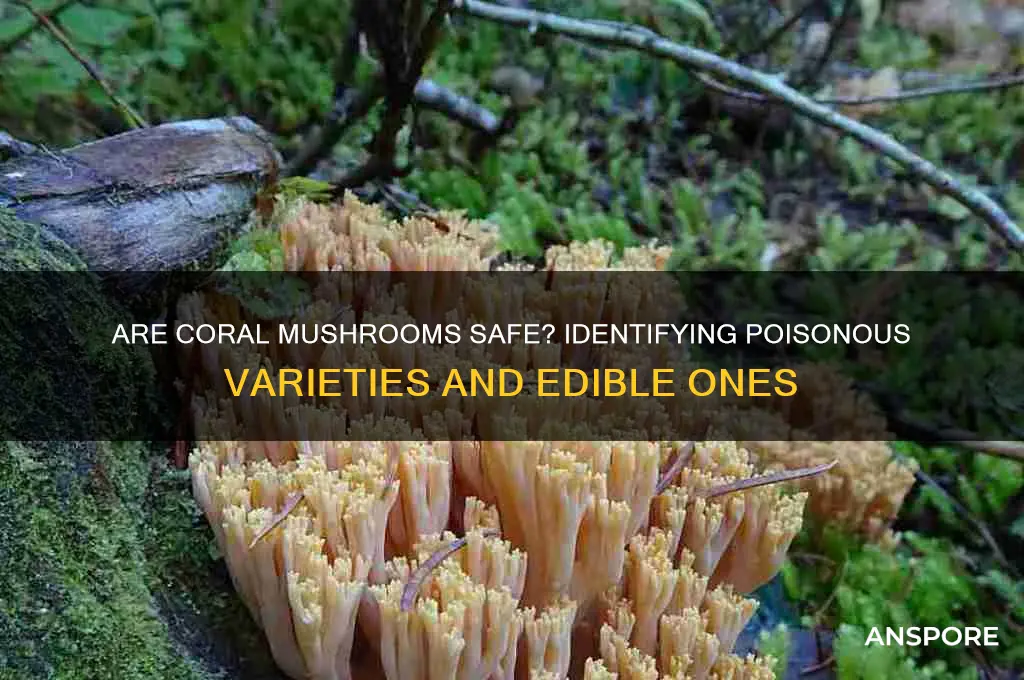

Coral mushrooms, known for their distinctive branching structures resembling underwater coral, are a fascinating group of fungi that often attract the attention of foragers and nature enthusiasts. While many species of coral mushrooms are considered edible and even prized for their mild flavor, it is crucial to approach them with caution, as not all varieties are safe to consume. Some coral mushrooms contain toxins that can cause gastrointestinal distress or more severe reactions, making accurate identification essential. Understanding which species are poisonous and which are safe is vital for anyone interested in foraging these unique fungi, as misidentification can lead to unpleasant or even dangerous consequences.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Identifying Poisonous Coral Mushrooms

Coral mushrooms, with their distinctive branching structures, often captivate foragers and nature enthusiasts. However, not all are safe to consume. While many species in the *Ramaria* genus are edible, some contain toxins that can cause gastrointestinal distress or more severe reactions. Identifying poisonous varieties requires careful observation of specific traits, as no single rule applies universally.

One key characteristic to examine is color. Poisonous coral mushrooms often display vivid, unnatural hues, such as bright red, orange, or yellow. For instance, *Ramaria formosa*, commonly known as the "Pinkish Coral," starts with pale tips that darken to a striking pink or red. While its appearance is alluring, it contains a toxin that causes sweating, vomiting, and diarrhea if ingested. In contrast, edible species like *Ramaria botrytis* (the "Cauliflower Coral") typically have more subdued, earthy tones.

Texture and spore color also provide clues. Poisonous corals often have brittle, easily breakable branches, whereas edible varieties tend to be more flexible. Examining the spore print can be insightful: toxic species often produce ochre or rusty-colored spores, while edible ones may yield lighter shades. For example, *Ramaria pallida*, a toxic species, leaves a distinct ochre spore print, distinguishing it from its safer counterparts.

Habitat and seasonality play a role too. Poisonous corals frequently grow in coniferous forests or areas with rich, acidic soil. Foraging during late summer or fall increases the likelihood of encountering toxic species, as this is their peak season. Always cross-reference multiple identification guides and, when in doubt, avoid consumption entirely. Misidentification can have serious consequences, as even small amounts of certain toxins can cause discomfort.

Finally, rely on expert guidance or local mycological societies for verification. While field guides and apps are helpful, they are not infallible. A single misidentified mushroom can ruin a meal—or worse. Prioritize caution over curiosity, and remember that the beauty of coral mushrooms lies in their observation, not necessarily their consumption.

Are Toadstool Mushrooms Poisonous? Unveiling the Truth Behind the Myth

You may want to see also

Symptoms of Coral Mushroom Poisoning

Coral mushrooms, with their vibrant, branching structures, often attract foragers, but not all are safe to consume. While many species, like the edible *Ramaria botrytis* (cauliflower mushroom), are harmless, others can cause severe poisoning. For instance, *Ramaria formosa* (the poisonous coral mushroom) contains a toxin that leads to gastrointestinal distress. Recognizing the symptoms of coral mushroom poisoning is crucial for prompt treatment and prevention of long-term harm.

Symptoms typically appear within 30 minutes to 2 hours after ingestion, depending on the amount consumed and individual sensitivity. The most common initial signs are gastrointestinal in nature: nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. These symptoms can be severe and may lead to dehydration, particularly in children or the elderly. Unlike some mushroom toxins that affect the nervous system, coral mushroom poisoning primarily targets the digestive tract, making it less likely to cause hallucinations or seizures. However, prolonged or severe cases can lead to electrolyte imbalances, requiring medical intervention.

In rare instances, individuals may experience allergic reactions, such as hives, swelling, or difficulty breathing. These symptoms suggest an immune response rather than direct toxicity and require immediate medical attention. It’s important to note that the severity of symptoms often correlates with the quantity consumed. A small bite may cause mild discomfort, while a larger portion can result in acute distress. If you suspect poisoning, induce vomiting only if advised by a poison control center or healthcare professional, as it may not always be appropriate.

Prevention is key when foraging for coral mushrooms. Always carry a reliable field guide or consult an expert to identify species accurately. Avoid consuming any mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity. If poisoning occurs, document the mushroom’s appearance (take a photo if possible) to aid in treatment. Seek medical help immediately, bringing a sample of the mushroom for identification. Early intervention can mitigate symptoms and prevent complications, ensuring a swift recovery.

Are Puff Mushrooms Poisonous? A Guide to Identifying and Safety

You may want to see also

Safe Coral Mushroom Species

Coral mushrooms, with their branching, colorful structures, often captivate foragers and nature enthusiasts. While some species are toxic, several are not only safe but also prized for their culinary and medicinal qualities. Identifying these edible varieties requires careful observation of characteristics like color, texture, and habitat. Among the safest are the Crimson Coral Mushroom (Ramaria sanguinea) and the Yellow Coral Mushroom (Ramaria flava), both known for their vibrant hues and lack of toxicity. However, always cross-reference findings with a reliable field guide or expert, as misidentification can lead to serious consequences.

Foraging for safe coral mushrooms begins with understanding their preferred environments. Most edible species thrive in woodland areas, particularly under coniferous trees. The Pine-Spined Coral (Ramaria araiospora) is a prime example, often found in pine forests and easily identified by its yellowish branches with reddish tips. When harvesting, use a sharp knife to cut the base, leaving the underground mycelium intact to encourage future growth. Avoid specimens growing near polluted areas or roadsides, as they may accumulate toxins. Proper preparation is equally crucial; always cook coral mushrooms thoroughly, as raw consumption can cause mild digestive discomfort even in non-toxic species.

One standout among safe coral mushrooms is the Waxy Cap Coral (Hygrophorus hypothejus), though it’s technically not a true coral mushroom, it shares a similar branching structure and is often grouped with them. This species is highly regarded in European cuisine for its nutty flavor and firm texture. To prepare, sauté in butter with garlic and herbs, or dry for long-term storage. Unlike some edible mushrooms, the Waxy Cap Coral retains its flavor well after drying, making it a versatile ingredient. However, its rarity in certain regions means foragers should prioritize sustainability, collecting only what they need.

For beginners, the Golden Coral Mushroom (Ramaria aurea) is an excellent starting point. Its bright yellow to orange branches and lack of toxic look-alikes make it relatively easy to identify. Found in deciduous and mixed forests, it often fruits in large clusters, providing a bountiful harvest. When cooking, pair it with robust flavors like thyme or rosemary to complement its mild, earthy taste. Always start with a small portion to test for individual sensitivities, as even safe mushrooms can occasionally cause reactions in certain people. With proper identification and preparation, these safe coral mushroom species offer both culinary delight and a deeper connection to the natural world.

Are Brown Mushrooms Poisonous? Identifying Safe and Toxic Varieties

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$7.62 $14.95

Common Toxic Look-Alikes

Coral mushrooms, with their branching, colorful structures, often attract foragers due to their unique appearance. However, not all coral-like fungi are safe to consume. Among the most notorious toxic look-alikes is the false coral (*Clavulinopsis species*), which mimics the vibrant hues of edible corals but lacks their delicate, brittle texture. Unlike true corals, false corals are often rubbery and may cause gastrointestinal distress if ingested. Always test for brittleness by snapping a small piece; if it bends, avoid it.

Another deceptive doppelgänger is the deadly coral (*Ramaria formosa*), found in North America and Europe. Its yellow to greenish branches resemble edible species like *Ramaria botrytis*, but it contains toxins that cause severe nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. A key identifier is its sharp, unpleasant odor, which contrasts with the mild or fruity scent of safe corals. If in doubt, perform a spore print test; *R. formosa* produces ochre spores, while edible corals typically produce white or yellow ones.

Foraging novices often mistake snake's head (*Aseroe rubra*) for coral mushrooms due to its reddish, branching structure. However, this fungus is not only toxic but also emits a putrid odor, earning it the nickname "anemone stinkhorn." Ingesting it can lead to immediate gastrointestinal symptoms, including cramps and diarrhea. Its slimy texture and foul smell are clear warnings, but misidentification in poor lighting or from a distance can still occur.

To avoid toxic look-alikes, follow these steps: 1) Research regional coral species and their toxic counterparts. 2) Carry a field guide or use a trusted mushroom identification app. 3) Never consume a mushroom unless 100% certain of its identity. 4) When in doubt, consult an expert or discard the specimen. Remember, while coral mushrooms can be a forager’s delight, their toxic mimics demand caution and respect.

Is Psilocybin Poisonous? Debunking Myths About Magic Mushrooms

You may want to see also

Prevention Tips for Foragers

Coral mushrooms, with their striking, branching forms, often tempt foragers with their beauty. However, not all are safe to eat. Some species, like *Ramaria formosa* (the pinkish-white coral), contain toxins that can cause gastrointestinal distress. Knowing which corals are edible requires more than a casual glance—it demands careful study and, ideally, expert guidance. For those venturing into foraging, prevention is paramount to avoid a potentially unpleasant or dangerous experience.

One of the most effective prevention strategies is to never rely on color or shape alone to identify coral mushrooms. While some edible species, like *Ramaria botrytis* (the cauliflower coral), are relatively safe, their toxic counterparts can resemble them closely. Always carry a detailed field guide or use a trusted mushroom identification app. Better yet, forage with an experienced mycologist who can provide real-time verification. If in doubt, leave it out—the risk of misidentification is never worth the reward.

Another critical prevention tip is to start small and test for tolerance. Even if you’re confident in your identification, some individuals may react adversely to edible coral mushrooms due to personal sensitivities. Begin by consuming a small amount (no more than a teaspoon) and wait 24 hours to monitor for any adverse effects. Symptoms like nausea, vomiting, or dizziness should prompt immediate medical attention. This cautious approach applies to all foraged mushrooms, not just corals.

Foraging in the right environment also minimizes risk. Avoid areas contaminated by pollutants, such as roadsides or industrial zones, as mushrooms readily absorb toxins from their surroundings. Opt for pristine, undisturbed habitats like forests or meadows. Additionally, always cut the mushroom at the base instead of uprooting it. This preserves the mycelium, ensuring the species can continue to grow and thrive in its ecosystem.

Finally, document your finds meticulously. Take clear photos from multiple angles, note the habitat, and record details like soil type, nearby trees, and weather conditions. This practice not only aids in accurate identification but also builds your foraging knowledge over time. Sharing these records with local mycological clubs can further enhance your skills and contribute to collective understanding. Prevention in foraging is as much about respect for nature as it is about personal safety.

Are Shiitake Mushrooms Poisonous? Debunking Myths and Facts

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, some coral mushrooms are poisonous. While many species in the *Ramaria* genus are edible, others contain toxins that can cause gastrointestinal distress or other adverse reactions.

Poisonous coral mushrooms often have a bitter taste or cause a stinging sensation on the tongue. However, taste alone is not a reliable method, so proper identification through field guides or expert advice is essential.

No, not all coral mushrooms are safe to eat. Some species, like *Ramaria formosa* (the pinkish-orange coral mushroom), are known to be toxic and should be avoided.

Symptoms can include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and in severe cases, dehydration. If you suspect poisoning, seek medical attention immediately.

Foraging for coral mushrooms as a beginner is risky due to the difficulty in distinguishing edible from poisonous species. It’s best to consult an experienced forager or mycologist before consuming any wild mushrooms.