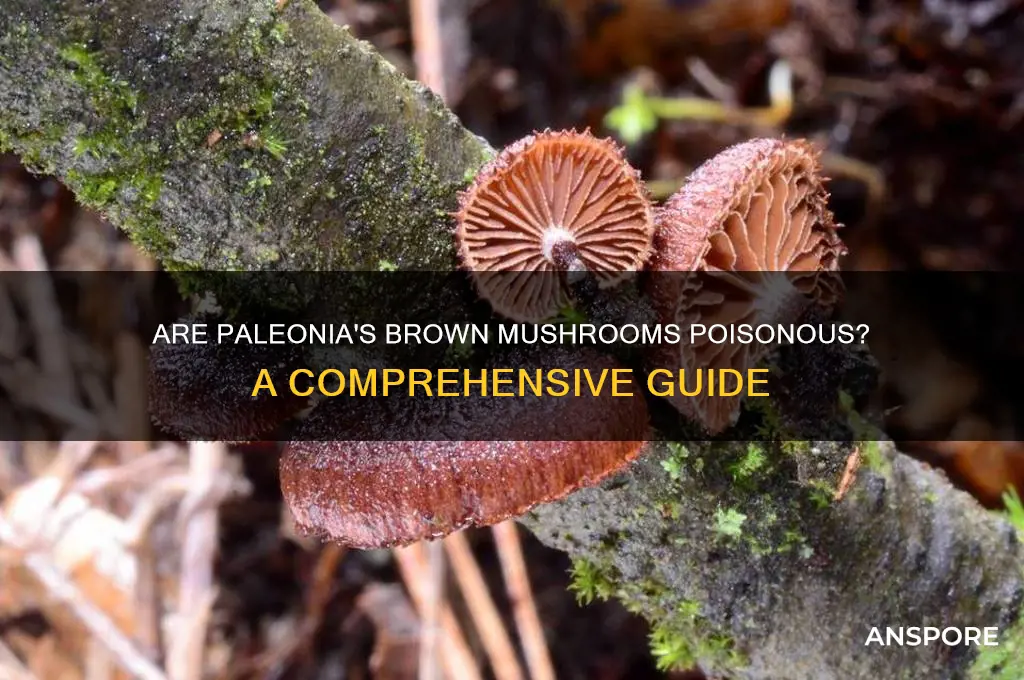

Brown mushrooms in Paleonia, a region known for its diverse fungal species, raise concerns about their edibility due to the potential presence of toxic varieties. While not all brown mushrooms in this area are poisonous, identifying them accurately is crucial, as some species can cause severe health issues or even be fatal if consumed. Common toxic varieties, such as the Paleonian Death Cap or the Fool’s Brown, resemble edible mushrooms, making proper identification essential. Consulting local mycological experts or using reliable field guides is highly recommended to avoid accidental poisoning when foraging in Paleonia.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Mushroom Type | Brown Mushrooms (Paleonia) |

| Toxicity | Generally considered non-toxic, but some species may cause mild gastrointestinal discomfort if consumed in large quantities. |

| Edibility | Most brown mushrooms in Paleonia are edible, but proper identification is crucial as some toxic species resemble edible ones. |

| Common Species | Paleonia Brown Cap, Forest Brown Mushroom, Paleonia Wood Mushroom |

| Toxic Species | None widely documented, but misidentification with toxic species (e.g., Galerina marginata) is a risk. |

| Symptoms (if toxic) | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain (if a toxic species is mistakenly consumed). |

| Habitat | Found in forested areas, often near decaying wood or soil rich in organic matter. |

| Identification Tips | Look for specific features like gill color, spore print, and stem characteristics to avoid confusion with toxic species. |

| Precaution | Always consult a mycologist or use a reliable field guide before consuming wild mushrooms. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Identifying Brown Mushrooms in Paleonia

Brown mushrooms in Paleonia present a unique challenge for foragers due to their diverse appearances and varying toxicity levels. Unlike regions with well-documented mycological profiles, Paleonia’s fungal ecosystem remains understudied, leaving many species unidentified or misclassified. This ambiguity necessitates a cautious, methodical approach to identification. For instance, the *Paleonia brunescens*, a common brown mushroom, shares morphological traits with both edible and toxic species, such as the *Amanita fuliginea*. Key distinguishing features include gill spacing, spore color, and the presence of a volva or ring on the stem. Without precise knowledge, even experienced foragers risk misidentification, underscoring the importance of cross-referencing multiple characteristics.

To safely identify brown mushrooms in Paleonia, follow a structured process that minimizes risk. Begin by examining the habitat—brown mushrooms often thrive in deciduous forests with high humidity, but specific species may prefer unique microenvironments. Next, assess the mushroom’s cap texture: is it smooth, scaly, or viscid? The *Boletus paleonicus*, for example, has a distinct velvety cap, while the toxic *Cortinarius paleoliensis* features a slimy surface. Smell is another critical factor; some brown mushrooms emit a fruity aroma, while others may smell pungent or earthy. Always carry a spore print kit to determine spore color, a reliable identifier. For instance, a brown mushroom with white spores is more likely to belong to the *Lactarius* genus, some of which are edible in small doses (up to 50 grams per adult).

Despite these methods, reliance on visual and sensory cues alone is insufficient. Chemical tests can provide additional clarity. Applying a drop of potassium hydroxide (KOH) to the mushroom’s cap or stem can induce color changes indicative of specific compounds. For example, the *Paleonia brunescens* turns reddish-brown when exposed to KOH, a trait not shared by its toxic lookalike, the *Amanita fuliginea*. However, such tests require precision and should be performed by individuals with prior training. Foraging guides specific to Paleonia, though rare, can also aid in identification. If in doubt, avoid consumption entirely—even a small bite of a toxic species can cause severe symptoms, including gastrointestinal distress, hallucinations, or organ failure, depending on the toxin involved.

Comparative analysis of brown mushrooms in Paleonia reveals patterns that can aid in identification. For instance, mushrooms with a central stem and gills are more likely to belong to the Agaricales order, which includes both edible and toxic species. In contrast, those with pores or tubes under the cap typically fall under the Boletales order, many of which are safe for consumption. However, exceptions abound; the *Boletus satanoides*, found in neighboring regions, resembles Paleonia’s brown boletes but is toxic when raw. Cooking neutralizes its toxins, but this knowledge is region-specific and cannot be assumed for Paleonian species. Such nuances highlight the need for localized research and caution.

In conclusion, identifying brown mushrooms in Paleonia demands a blend of observational skill, scientific rigor, and humility. While certain features—like spore color, habitat, and chemical reactions—offer valuable clues, no single characteristic guarantees safety. Foraging should be approached as an educational endeavor, not a culinary gamble. Documenting findings, consulting local experts, and avoiding consumption unless absolutely certain are essential practices. As Paleonia’s fungal diversity continues to be explored, foragers must prioritize safety over curiosity, ensuring that the region’s mushrooms remain a subject of study rather than a source of harm.

Home Remedies for Mushroom Poisoning: Quick and Safe Treatment Tips

You may want to see also

Common Toxic Species in the Region

In the Paleonia region, several brown mushroom species pose significant health risks, making accurate identification crucial for foragers. Among these, the Paleonia Brown Hood (Stropharia paleonica) stands out due to its deceptive resemblance to edible varieties. Its cap, ranging from 5 to 10 cm in diameter, often fools collectors into mistaking it for the benign Meadow Mushroom. However, ingestion of even a small portion (approximately 30 grams) can lead to severe gastrointestinal symptoms, including vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain, within 1-2 hours. Long-term effects, though rare, may include liver irritation if consumed repeatedly.

Another notorious species is the Spotted Paleonia Conifer (Amanita paleoniensis), characterized by its brown cap speckled with white flakes. This mushroom contains amatoxins, potent toxins that can cause life-threatening liver and kidney damage. Symptoms may not appear until 6-24 hours after consumption, delaying treatment and increasing risk. A single cap, roughly 8-12 cm wide, contains enough toxin to induce organ failure in adults, while children are at higher risk due to their lower body mass. Immediate medical attention is essential if ingestion is suspected.

Foraging safely requires adherence to specific guidelines. Always carry a detailed field guide or consult a mycologist when uncertain. Avoid mushrooms with white gills and a bulbous base, as these traits are common in toxic species like the Paleonia Conifer. Cooking does not neutralize toxins in these mushrooms, so visual inspection alone is insufficient. Additionally, cross-reference findings with multiple sources, as regional variations in appearance can complicate identification.

Comparatively, the Hairy Brown Paleonia (Hypholoma paleonicum) is less lethal but still dangerous. Its brown cap, covered in fine hairs, distinguishes it from smoother edible species. Consumption typically results in mild to moderate symptoms, such as nausea and dizziness, within 30 minutes to 2 hours. While rarely fatal, its effects can be prolonged, lasting up to 48 hours. This species often grows in clusters on decaying wood, a habitat foragers should approach with caution.

In conclusion, the Paleonia region’s toxic brown mushrooms demand respect and vigilance. By familiarizing oneself with key identifiers—such as cap patterns, gill colors, and growth habitats—foragers can minimize risk. When in doubt, err on the side of caution and discard questionable specimens. Education and preparedness are the most effective tools in avoiding the dangers these species present.

Are Yard Mushrooms Poisonous to Dogs? Essential Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Symptoms of Mushroom Poisoning

Mushroom poisoning symptoms can manifest within minutes or hours after ingestion, depending on the toxin involved. Amatoxins, found in deadly species like the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*), cause a delayed onset, often 6-24 hours after consumption. Initially, symptoms mimic gastroenteritis—severe abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea—which can lead to dehydration. Unlike typical food poisoning, this phase is followed by a false "recovery" period, only to worsen into liver and kidney failure within 48-72 hours. Even small doses (as little as 30mg of amatoxins) can be fatal without immediate medical intervention.

In contrast, muscarine poisoning, associated with certain *Clitocybe* and *Inocybe* species, acts rapidly, often within 15-30 minutes. Symptoms include excessive salivation, sweating, tear production, and gastrointestinal distress. While rarely fatal, the cholinergic effects—muscle spasms, blurred vision, and bronchial secretions—can be alarming. Treatment focuses on supportive care, such as atropine administration to counteract muscarinic effects. Unlike amatoxin poisoning, muscarine toxicity typically resolves within 24 hours without long-term damage.

Orellanine, found in mushrooms like the Fool’s Webcap (*Cortinarius orellanus*), causes a unique delayed nephrotoxicity. Symptoms appear 2-3 days post-ingestion, starting with nonspecific complaints like fatigue, thirst, and joint pain. Progressive kidney failure follows, often requiring dialysis. Misidentification of these brown mushrooms is common due to their nondescript appearance, emphasizing the need for expert verification before consumption. Even cooking does not destroy orellanine, making avoidance the only safe strategy.

Children and pets are particularly vulnerable to mushroom poisoning due to their lower body mass and tendency to ingest unknown substances. For instance, ibotenic acid in *Amanita muscaria* (fly agaric) causes hallucinations, confusion, and seizures in small doses (1-2 mushrooms). While rarely lethal, the psychoactive effects can be terrifying for both children and adults. Immediate decontamination—inducing vomiting or administering activated charcoal—can reduce toxin absorption, but professional medical evaluation is essential.

Practical tips for prevention include avoiding wild mushroom foraging without expert guidance, teaching children and pets to steer clear of fungi, and storing mushrooms out of reach. If poisoning is suspected, document the mushroom’s appearance (photographs are ideal) and contact a poison control center immediately. Time is critical, especially with amatoxin or orellanine exposure, where early intervention can mean the difference between recovery and organ failure. When in doubt, throw it out—no meal is worth the risk.

Are Brown Mushrooms Poisonous? Identifying Safe and Toxic Varieties

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Safe Foraging Practices in Paleonia

In Paleonia, where the forests teem with a variety of fungi, distinguishing between edible and poisonous brown mushrooms is a skill honed through knowledge and caution. The region’s damp, shaded environments foster species like the *Paleonian Brown Cap*, which resembles the toxic *False Paleonian Brown* but lacks its distinctive black gills. Misidentification can lead to severe gastrointestinal distress or worse, making proper identification critical. Always carry a reliable field guide or consult local mycologists before harvesting.

Foraging safely begins with understanding habitat cues. Brown mushrooms in Paleonia often thrive near deciduous trees, particularly oak and beech, but toxic varieties may prefer coniferous areas. Time of year matters too; late summer to early autumn is peak season, yet some poisonous species emerge earlier. Avoid mushrooms growing near polluted areas or roadsides, as they can accumulate toxins. A clean, untainted environment is a good initial indicator, but never a guarantee of safety.

Children under 12 and pets should never handle or consume wild mushrooms, as their systems are more susceptible to toxins. For adults, start with a small sample—no more than 1 ounce (28 grams) of a new species—and wait 24 hours to check for adverse reactions. Cooking mushrooms thoroughly can reduce certain toxins, but this is not a foolproof method for poisonous varieties. If in doubt, discard the specimen entirely.

One practical tip is the "spore print test." Place the cap gills-down on white paper overnight. The *Paleonian Brown Cap* produces a brown spore print, while the *False Paleonian Brown* yields a dark green one. This method, combined with examining gill color, cap texture, and stem features, increases accuracy. However, rely on multiple identifiers, as no single trait is definitive.

Finally, join local foraging groups or workshops to learn from experienced foragers. Paleonia’s mycological societies often host guided walks, offering hands-on practice in safe identification. Documenting finds with photos and notes can also build personal expertise over time. Remember, the goal is not just to find mushrooms, but to ensure every harvest is both safe and sustainable.

Are White Mushrooms Poisonous to Dogs? Essential Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Edible vs. Poisonous Look-Alikes

In the world of fungi, appearances can be deceiving. The brown mushrooms of Paleonia, often admired for their earthy tones and forest-floor charm, are a prime example of nature's trickery. Among these, the edible varieties like the Paleonian Brown Cap (*Paleonia brunneola*) offer a delightful culinary experience, but their doppelgängers, such as the Toxic Twin (*Veneficus similatus*), can be deadly. The key to safe foraging lies in understanding the subtle differences between these look-alikes, which often require more than a casual glance to distinguish.

Take, for instance, the gill structure. The *Paleonia brunneola* boasts gills that are closely spaced and have a slightly serrated edge, while the *Veneficus similatus* has gills that are farther apart and uniformly smooth. Another critical feature is the spore print. Edible brown mushrooms typically produce a creamy white or light brown spore print, whereas their poisonous counterparts often yield a darker, greenish-brown print. Foragers should always carry a spore print kit and a magnifying glass to examine these details, as they can be the difference between a gourmet meal and a trip to the emergency room.

Beyond physical characteristics, habitat plays a crucial role in identification. Edible brown mushrooms in Paleonia are commonly found in well-drained, deciduous forests, often near oak or beech trees. Poisonous look-alikes, however, tend to favor damp, shadowy areas with decaying matter. Foraging in the wrong location can increase the risk of misidentification. Always note the environment where the mushroom is growing and cross-reference it with known habitats for both edible and toxic species.

A practical tip for beginners is to start with a mentor or a guided foraging group. Even experienced foragers can fall victim to look-alikes, so sharing knowledge and observations can provide an extra layer of safety. Additionally, avoid consuming any mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity. If in doubt, throw it out. Symptoms of poisoning can appear anywhere from 20 minutes to 24 hours after ingestion, depending on the toxin, and may include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and in severe cases, organ failure.

Finally, consider the role of technology in modern foraging. Smartphone apps and online databases can be useful tools, but they should never replace hands-on knowledge and critical thinking. Apps like *Mushroom ID* or *PictureThis* can provide quick references, but always verify their findings with multiple sources. Remember, the forest is a beautiful but unforgiving teacher, and the price of a mistake can be steep. Approach foraging with respect, caution, and a commitment to continuous learning.

Are Bitter Mushrooms Poisonous? Unraveling the Truth About Toxic Fungi

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all brown mushrooms in Paleonia are poisonous. Some are edible, but proper identification is crucial as many toxic species also exist.

Identifying edible brown mushrooms requires knowledge of specific characteristics like cap shape, gill color, and spore print. Consulting a mycologist or using a reliable field guide is recommended.

Yes, some common poisonous brown mushrooms in Paleonia include species resembling the Deadly Galerina or the False Morel. Always avoid consumption unless certain of identification.

Symptoms can range from mild gastrointestinal distress to severe organ failure, depending on the species. Seek medical attention immediately if poisoning is suspected.

Foraging without expert guidance is risky due to the presence of toxic species. It’s best to learn from experienced foragers or join a mycological society before attempting to collect mushrooms.