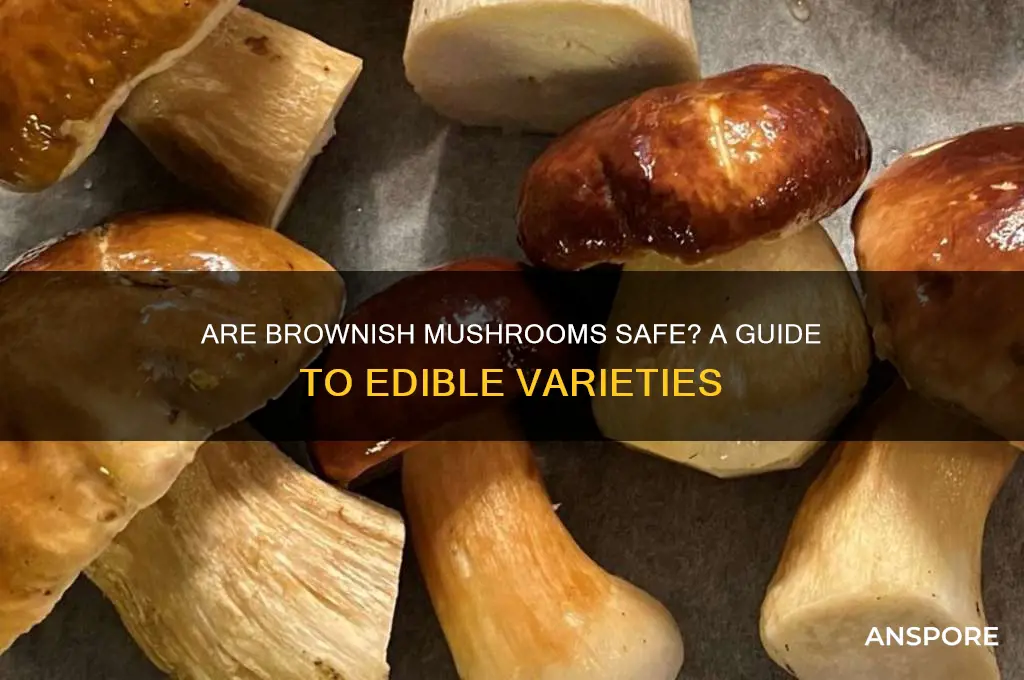

When encountering brownish mushrooms in the wild or at the market, it’s natural to wonder whether they are safe to eat. The color brown itself is not a reliable indicator of edibility, as both toxic and edible mushrooms can exhibit this hue. Factors such as species, habitat, and physical characteristics play a crucial role in determining safety. For instance, the common button mushroom is brown and widely consumed, while the deadly galerina, also brown, is highly poisonous. Without proper identification, consuming brownish mushrooms can pose serious risks, including severe illness or even fatality. Always consult a mycologist or use a reputable field guide to ensure accurate identification before consuming any wild mushrooms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Color | Brownish mushrooms can vary in shade, from light tan to dark brown. Color alone is not a reliable indicator of safety. |

| Gill Attachment | Check if the gills are attached or free from the stem. Some toxic mushrooms have attached gills, but this is not exclusive. |

| Spore Print | Take a spore print by placing the cap on paper overnight. Brownish mushrooms may have white, brown, or black spores, but spore color alone is not definitive. |

| Bruising | Some toxic mushrooms bruise blue, brown, or black when handled, but not all safe mushrooms avoid bruising. |

| Ring or Volva | The presence of a ring (annulus) or volva (cup-like base) can indicate toxicity in some species, but not all toxic mushrooms have these features. |

| Smell and Taste | Avoid tasting or smelling mushrooms for identification. Some toxic species have pleasant odors or tastes, while safe ones may have strong, unpleasant smells. |

| Habitat | Note where the mushroom grows. Some toxic species prefer specific environments, but habitat alone is not a reliable indicator. |

| Common Species | Examples of safe brownish mushrooms include Porcini (Boletus edulis) and Chanterelles (Cantharellus cibarius). Toxic examples include Galerina marginata and Amanita species. |

| Expert Identification | Always consult a mycologist or use a reliable field guide for accurate identification. Misidentification can be fatal. |

| General Rule | When in doubt, throw it out. Do not consume any mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Identifying edible vs. poisonous brownish mushrooms

When identifying edible vs. poisonous brownish mushrooms, it's crucial to approach the task with caution and knowledge. Brownish mushrooms encompass a wide variety of species, some of which are safe to eat, while others can be toxic or even deadly. The first step is to understand that color alone is not a reliable indicator of edibility. Many poisonous mushrooms, such as the deadly Galerina marginata, have brownish hues, while edible varieties like the chanterelle also fall within this color range. Therefore, a comprehensive examination of physical characteristics, habitat, and other identifying features is essential.

One key aspect to consider is the cap and stem structure. Edible brownish mushrooms often have distinct features like a central stem, gills that are not attached to the stem (free gills), and a cap that may be convex or vase-shaped. For example, the edible Lion's Mane mushroom has a shaggy, brownish cap with dangling spines. In contrast, poisonous mushrooms like the Amanita species often have a bulbous base, a skirt-like ring on the stem, and gills that are tightly attached. Observing these structural details can help differentiate between safe and toxic varieties.

Another critical factor is the spore print. This involves placing the cap of the mushroom on a piece of paper or glass overnight to capture the color of its spores. Edible brownish mushrooms like the Porcini (Cep) typically produce a brown spore print, while some poisonous species may have white, green, or black spores. However, spore color alone is not definitive, as some toxic mushrooms also produce brown spores. This method should be used in conjunction with other identification techniques.

The habitat and season of the mushroom also provide valuable clues. Edible brownish mushrooms often grow in specific environments, such as under certain trees (e.g., chanterelles near oak or birch) or in particular soil types. Poisonous mushrooms, on the other hand, may appear in less predictable locations. Additionally, knowing the typical season for a mushroom's growth can help narrow down its identity. For instance, the edible Honey Mushroom (Armillaria mellea) is commonly found in the fall, while some toxic species may appear earlier in the year.

Lastly, smell and taste tests can offer additional insights, but they should never be the sole method of identification. Some edible brownish mushrooms, like the Shaggy Mane, have a pleasant, earthy aroma, while others may smell fruity or nutty. Poisonous mushrooms can have foul odors or no smell at all. However, tasting a mushroom to test its edibility is extremely dangerous, as even a small amount of a toxic species can cause severe harm. Always rely on visual and environmental cues first and consult expert guides or mycologists when in doubt.

In summary, identifying edible vs. poisonous brownish mushrooms requires a meticulous examination of physical traits, spore prints, habitat, and seasonal patterns. While some features may suggest edibility, no single characteristic guarantees safety. Always exercise caution, avoid consuming wild mushrooms without certainty, and seek guidance from experienced foragers or mycological resources to ensure a safe and enjoyable mushroom-hunting experience.

Do Crickets Eat Mushrooms? Unveiling Their Dietary Habits and Preferences

You may want to see also

Common safe brownish mushroom species

When considering whether brownish mushrooms are safe to eat, it’s essential to identify specific species, as not all brown mushrooms are edible. Among the common safe brownish mushroom species, the Porcini (Boletus edulis) stands out as a highly prized edible mushroom. Porcini mushrooms are characterized by their brown caps, stout stems, and spongy pores under the cap instead of gills. They are widely found in Europe, North America, and Asia and are celebrated for their rich, nutty flavor. Always ensure the mushroom has a porous underside and lacks any red or yellow stains when cut, as these could indicate a toxic look-alike.

Another safe brownish mushroom is the Chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius), known for its golden-brown color and wavy, forked gills. Chanterelles have a fruity aroma and are commonly found in forests across North America, Europe, and Asia. They are easily identifiable by their trumpet-like shape and false gills that run down the stem. When foraging for chanterelles, avoid confusing them with the toxic Jack-O-Lantern mushroom, which has true gills and a sharper, unpleasant odor.

The Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) is a common safe brownish species, though it can also appear in shades of gray or white. Named for its oyster shell-like shape, this mushroom grows on wood and has a mild, savory flavor. Oyster mushrooms are easy to identify due to their fan-like caps, decurrent gills (gills that run down the stem), and lack of a distinct ring or volva. They are a popular choice for both foragers and cultivators.

The Lion’s Mane Mushroom (Hericium erinaceus) is a unique safe brownish species, known for its shaggy, icicle-like spines instead of gills. This mushroom grows on hardwood trees and has a mild, seafood-like flavor, often compared to crab or lobster. Lion’s Mane is easily distinguishable from other mushrooms due to its distinctive appearance and is gaining popularity for its culinary and potential health benefits.

Lastly, the Shaggy Mane (Coprinus comatus) is a safe brownish mushroom with a tall, cylindrical cap covered in shaggy scales. It is typically found in grassy areas and has a delicate, earthy flavor. However, it must be harvested young, as mature specimens autodigest and become inky and unsafe to eat. Always ensure the cap is still shaggy and white at the base when foraging for this species.

When foraging for these common safe brownish mushroom species, always follow proper identification guidelines, consult field guides or experts, and avoid consuming any mushroom unless you are absolutely certain of its identity. Misidentification can lead to serious poisoning, so caution is paramount.

Yard Mushrooms: Safe to Eat or Toxic Threat?

You may want to see also

Toxic brownish mushrooms to avoid

When foraging for mushrooms, it's crucial to be aware of toxic brownish varieties that can cause severe health issues or even be fatal if consumed. One notorious example is the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*), which has a brownish or yellowish-brown cap. Despite its unassuming appearance, it contains amatoxins that can cause liver and kidney failure. The Death Cap is often mistaken for edible mushrooms like the Paddy Straw mushroom, making proper identification essential. Always avoid any brownish mushroom with a bulbous base and a skirt-like ring on the stem, as these are hallmark features of this deadly species.

Another toxic brownish mushroom to avoid is the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera* and related species). Its light brown to white cap and delicate appearance belie its extreme toxicity. Like the Death Cap, it contains amatoxins, and even a small bite can lead to severe poisoning. The Destroying Angel often grows in wooded areas and can resemble edible button mushrooms, making it a dangerous look-alike. If you encounter a brownish mushroom with a cup-like base and a smooth cap, it's best to leave it undisturbed.

The Galerina species, often brown in color, are another group of toxic mushrooms to steer clear of. These small, unassuming fungi contain the same deadly amatoxins found in the Death Cap and Destroying Angel. Galerinas are commonly found growing on wood and can easily be mistaken for edible mushrooms like the Honey Mushroom. Their brownish caps and slender stems make them difficult to identify without careful examination. If you're unsure, it's safer to avoid any brownish mushrooms growing on wood or stumps.

Lastly, the False Morel (*Gyromitra esculenta*) is a brownish mushroom that poses significant risks. While some foragers cook and consume it, it contains gyromitrin, a toxin that can cause severe gastrointestinal symptoms and, in extreme cases, organ failure. False Morels have a brain-like, wrinkled cap that distinguishes them from true morels. Their brownish color and unique appearance can be enticing, but their toxicity makes them a poor choice for consumption. Always opt for true morels, which have a honeycomb-like cap and are safe when properly prepared.

In summary, toxic brownish mushrooms like the Death Cap, Destroying Angel, Galerina, and False Morel should be avoided at all costs. Their deceptive appearances and deadly toxins make accurate identification critical. When in doubt, follow the rule: "There are old foragers and bold foragers, but no old, bold foragers." Stick to well-known edible species and consult expert guides or mycologists if you're unsure. Your safety is paramount when exploring the world of mushrooms.

Delicious Ways to Enjoy Lion's Mane Mushroom in Your Daily Meals

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$5.49 $6.49

Symptoms of brownish mushroom poisoning

Brownish mushrooms can vary widely in terms of edibility, and consuming the wrong type can lead to severe poisoning. Symptoms of brownish mushroom poisoning depend on the specific toxins present in the mushroom species ingested. Generally, these symptoms can manifest within minutes to several hours after consumption, depending on the type of toxin involved. It is crucial to recognize these symptoms early to seek immediate medical attention.

One common group of toxins found in poisonous brownish mushrooms is amatoxins, which are present in species like the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*). Symptoms of amatoxin poisoning typically appear in two phases. Initially, within 6 to 24 hours after ingestion, individuals may experience severe gastrointestinal distress, including nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. This phase may subside temporarily, giving a false sense of recovery. However, within 24 to 48 hours, the toxins begin to cause severe liver and kidney damage, leading to symptoms such as jaundice, confusion, seizures, and in severe cases, liver failure and death.

Another toxin to be aware of is orellanine, found in mushrooms like the Fool’s Webcap (*Cortinarius orellanus*). Orellanine poisoning symptoms usually appear 2 to 3 days after ingestion and primarily affect the kidneys. Early signs include thirst, frequent urination, and fatigue, followed by acute kidney injury, which can manifest as reduced urine output, swelling, and in severe cases, kidney failure requiring dialysis. Unlike amatoxin poisoning, orellanine toxicity does not typically cause gastrointestinal symptoms initially, making it harder to diagnose early.

Some brownish mushrooms contain muscarine, a toxin found in species like the Inky Cap mushrooms (*Clitocybe* genus). Muscarine poisoning symptoms appear quickly, often within 15 to 30 minutes after ingestion. These symptoms include excessive salivation, sweating, tearing, blurred vision, abdominal cramps, and diarrhea. In severe cases, it can lead to difficulty breathing, low blood pressure, and even respiratory failure. These symptoms are due to the toxin’s stimulation of the parasympathetic nervous system.

Lastly, gyromitrin toxicity, found in mushrooms like the False Morel (*Gyromitra esculenta*), causes symptoms that typically appear within 6 to 12 hours after ingestion. Initial symptoms include gastrointestinal distress, such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, followed by neurological symptoms like dizziness, headache, and confusion. Severe cases can lead to seizures, coma, and even death. Gyromitrin is converted into a toxic compound in the body, which damages cells and disrupts normal metabolic processes.

If you suspect brownish mushroom poisoning, it is essential to seek medical help immediately. Bring a sample of the mushroom or a photograph for identification, as this can aid in treatment. Do not wait for symptoms to worsen, as some toxins can cause irreversible damage within hours. Always exercise caution and consult a mycologist or use a reliable field guide before consuming wild mushrooms.

Mastering Morel Mushrooms: A Step-by-Step Guide to Preparation and Cooking

You may want to see also

Safe cooking methods for brownish mushrooms

When it comes to cooking brownish mushrooms, safety is paramount. While many brownish mushrooms, such as cremini, portobello, and shiitake, are safe to eat, proper preparation is essential to eliminate any potential risks. The first step in safe cooking is to ensure the mushrooms are thoroughly cleaned. Use a damp cloth or brush to gently remove dirt and debris, as soaking them in water can cause them to absorb excess moisture, affecting their texture during cooking. Cleaning them properly reduces the risk of ingesting harmful contaminants that might be present on the surface.

After cleaning, it’s crucial to cook brownish mushrooms at the right temperature and for an adequate duration. Heat plays a vital role in breaking down potentially harmful compounds and killing any bacteria or parasites. Sautéing, grilling, roasting, or boiling are effective methods to ensure the mushrooms reach a safe internal temperature. For example, sautéing brownish mushrooms in a pan with oil or butter over medium-high heat for at least 5-7 minutes ensures they are cooked through. Similarly, roasting them in an oven at 375°F (190°C) for 20-25 minutes guarantees even cooking and eliminates any risks associated with undercooking.

Another safe cooking method is boiling or simmering brownish mushrooms in soups, stews, or sauces. This method not only cooks the mushrooms thoroughly but also allows their flavors to infuse into the dish. When boiling, ensure the mushrooms are submerged in the liquid and cook for at least 10-15 minutes. This prolonged exposure to heat ensures any potential toxins or microorganisms are neutralized. Boiling is particularly useful for tougher varieties of brownish mushrooms, as it helps tenderize them while ensuring safety.

Grilling is another excellent option for cooking brownish mushrooms, especially larger varieties like portobello. Preheat the grill to medium-high heat and brush the mushrooms with oil to prevent sticking. Grill them for 4-6 minutes on each side, ensuring they develop grill marks and become tender. Grilling not only enhances their flavor but also ensures they are cooked thoroughly, reducing any risks associated with raw or undercooked mushrooms. Always use a food thermometer to check the internal temperature, which should reach at least 160°F (71°C) for safety.

Lastly, proper storage and handling are integral to safe cooking. Fresh brownish mushrooms should be stored in the refrigerator in a paper bag or loosely wrapped in a cloth to maintain their freshness. Avoid storing them in plastic bags, as this can trap moisture and accelerate spoilage. Cooked mushrooms should be consumed within 3-4 days or frozen for longer storage. Reheat cooked mushrooms to an internal temperature of 165°F (74°C) before consuming to ensure any bacteria that may have developed are eliminated. By following these safe cooking methods, you can enjoy brownish mushrooms without compromising on health or flavor.

Are Brown Spotted Mushrooms Safe to Eat? A Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all brownish mushrooms are safe to eat. While some edible mushrooms, like chanterelles and porcini, have brownish hues, others, such as the deadly galerina or poisonous cortinarius species, are also brown. Always identify mushrooms accurately before consuming.

Identifying safe brownish mushrooms requires knowledge of specific characteristics like cap shape, gill structure, spore color, and habitat. Consulting a field guide, using a mushroom identification app, or seeking advice from an expert mycologist is recommended.

Yes, store-bought brownish mushrooms, such as cremini or portobello, are safe to eat as they are commercially cultivated and regulated for consumption. However, wild-harvested mushrooms should be identified with caution.

If you suspect mushroom poisoning, seek immediate medical attention. Bring a sample of the mushroom or a photo for identification. Symptoms can range from mild gastrointestinal issues to severe toxicity, so prompt action is crucial.

![Parmalat: Italian "Panna Chef ai Funghi Porcini", UHT Long Life Cooking Cream with brown edible mushroom 6.7 Fluid Ounce (200ml) Packages (Pack of 3) [ Italian Import ]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71Z+-qSvbIL._AC_UL320_.jpg)