The question of whether *Coprinus* mushrooms are part of a tissue requires an understanding of both fungal biology and the definition of biological tissues. In multicellular organisms, tissues are groups of cells that work together to perform a specific function. However, fungi, including *Coprinus* mushrooms, have a unique structure composed of thread-like filaments called hyphae, which collectively form the mycelium. While the fruiting body of a *Coprinus* mushroom (the visible mushroom) consists of specialized hyphal structures, it does not fit the conventional definition of a tissue as seen in plants or animals. Instead, fungal structures are often described in terms of their hyphal organization and function, making the concept of tissue less applicable in the fungal kingdom. Thus, *Coprinus* mushrooms are not considered part of a tissue in the traditional biological sense.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Coprinus mushroom structure overview: Examines the basic anatomy of Coprinus mushrooms, including their fruiting bodies

- Tissue classification in fungi: Explores how fungal tissues are categorized and defined in mycology

- Coprinus cellular composition: Analyzes the cell types and arrangement in Coprinus mushrooms

- Tissue vs. non-tissue debate: Discusses whether Coprinus mushrooms meet the criteria for being considered tissue

- Comparative fungal tissue analysis: Compares Coprinus tissue structure with other mushroom species

Coprinus mushroom structure overview: Examines the basic anatomy of Coprinus mushrooms, including their fruiting bodies

Coprinus mushrooms, commonly known as inky caps, exhibit a distinctive structure that is both fascinating and complex. Their anatomy is primarily characterized by their fruiting bodies, which are the visible, above-ground parts of the fungus. These fruiting bodies play a crucial role in the mushroom's life cycle, serving as the reproductive structures that release spores. Unlike some other mushrooms, Coprinus species often have delicate, short-lived fruiting bodies that undergo autodigestion, a process where the gills dissolve into a black, inky liquid, giving them their colloquial name.

The fruiting body of a Coprinus mushroom consists of several key components. The pileus (cap) is the umbrella-like structure at the top, which varies in shape from conical to bell-shaped depending on the species and maturity. Beneath the cap lies the gills, which are thin, closely spaced structures where spores are produced. The gills of Coprinus mushrooms are particularly notable for their deliquescent nature, meaning they self-digest as part of the mushroom's spore dispersal mechanism. This unique feature is a defining characteristic of the genus.

Another essential part of the Coprinus mushroom structure is the stipe (stem), which supports the cap and gills. The stipe is typically slender and fragile, often hollow, and may be ringed or smooth depending on the species. It anchors the fruiting body to the substrate, such as soil or decaying wood, where the mushroom's mycelium (the vegetative part of the fungus) resides. The mycelium itself is a network of thread-like hyphae that absorb nutrients from the environment, though it is not part of the fruiting body tissue.

The veil is another noteworthy feature in young Coprinus mushrooms. It is a thin membrane that covers the gills during the mushroom's early development stages, protecting the developing spores. As the cap expands, the veil tears, often leaving remnants as a ring on the stipe or fragments on the cap's edge. This veil is a temporary tissue that disintegrates as the mushroom matures, highlighting the dynamic nature of Coprinus anatomy.

In summary, the structure of Coprinus mushrooms is intricately designed to support their reproductive function. The fruiting body, comprising the cap, gills, stipe, and veil, works in harmony to produce and disperse spores. While the fruiting body is a tissue-like structure, it is distinct from the mycelium, which forms the bulk of the fungus's biomass. Understanding the anatomy of Coprinus mushrooms provides insight into their unique adaptations and ecological roles, making them a compelling subject for mycological study.

Psychedelic Mushroom Visions: What Do You See?

You may want to see also

Tissue classification in fungi: Explores how fungal tissues are categorized and defined in mycology

Fungal tissues, unlike those of plants and animals, are uniquely structured and serve distinct functions in the growth, reproduction, and survival of fungi. Mycology, the study of fungi, categorizes these tissues based on their composition, organization, and role within the fungal organism. Fungi are primarily composed of eukaryotic cells that form filamentous structures called hyphae, which aggregate to create more complex arrangements known as mycelium. These structures are the foundation for classifying fungal tissues. The primary tissues in fungi include vegetative and reproductive types, each with specialized functions that contribute to the organism's life cycle.

Vegetative tissues in fungi are responsible for growth, nutrient absorption, and structural support. The mycelium, a network of hyphae, is the primary vegetative tissue. Hyphae can be further classified into septate (with cross-walls) or coenocytic (without cross-walls) types, depending on the fungal species. In some fungi, like the Coprinus mushroom, the mycelium forms the bulk of the organism and is crucial for nutrient uptake and colonization of substrates. This tissue is often categorized based on its cellular organization, wall composition (e.g., chitin), and metabolic activity. Understanding the structure of vegetative tissues is essential for identifying fungal species and their ecological roles.

Reproductive tissues in fungi are specialized for the production and dispersal of spores, the primary means of fungal reproduction. These tissues are often differentiated from vegetative tissues and include structures like fruiting bodies, sporocarps, and spore-bearing surfaces. In the case of Coprinus mushrooms, the fruiting body is a reproductive tissue that develops from the mycelium under specific environmental conditions. This tissue is transient and serves solely to produce and release spores. Mycologists classify reproductive tissues based on their morphology, spore type (e.g., basidiospores in Coprinus), and developmental processes, which are critical for fungal taxonomy and identification.

The classification of fungal tissues also considers their ecological and functional roles. For instance, some fungi form symbiotic associations with plants (mycorrhizae), where specialized tissues facilitate nutrient exchange between the organisms. In Coprinus and other saprotrophic fungi, tissues are adapted for decomposing organic matter, playing a vital role in nutrient cycling. Tissue classification in mycology thus integrates structural, functional, and ecological criteria to provide a comprehensive understanding of fungal biology. This approach helps researchers and mycologists study fungal diversity, evolution, and applications in fields like medicine, agriculture, and biotechnology.

In exploring whether Coprinus mushrooms are part of a tissue, it is clear that they represent reproductive tissues (fruiting bodies) arising from the vegetative mycelium. This distinction highlights the dynamic nature of fungal tissues and their adaptability to different life cycle stages. Mycological classification emphasizes the importance of both vegetative and reproductive tissues in defining fungal organisms, offering insights into their complex biology and ecological significance. By studying tissue categorization, scientists can better understand fungi's roles in ecosystems and their potential for human use.

Mushroom Leather: Eco-Friendly and Biodegradable?

You may want to see also

Coprinus cellular composition: Analyzes the cell types and arrangement in Coprinus mushrooms

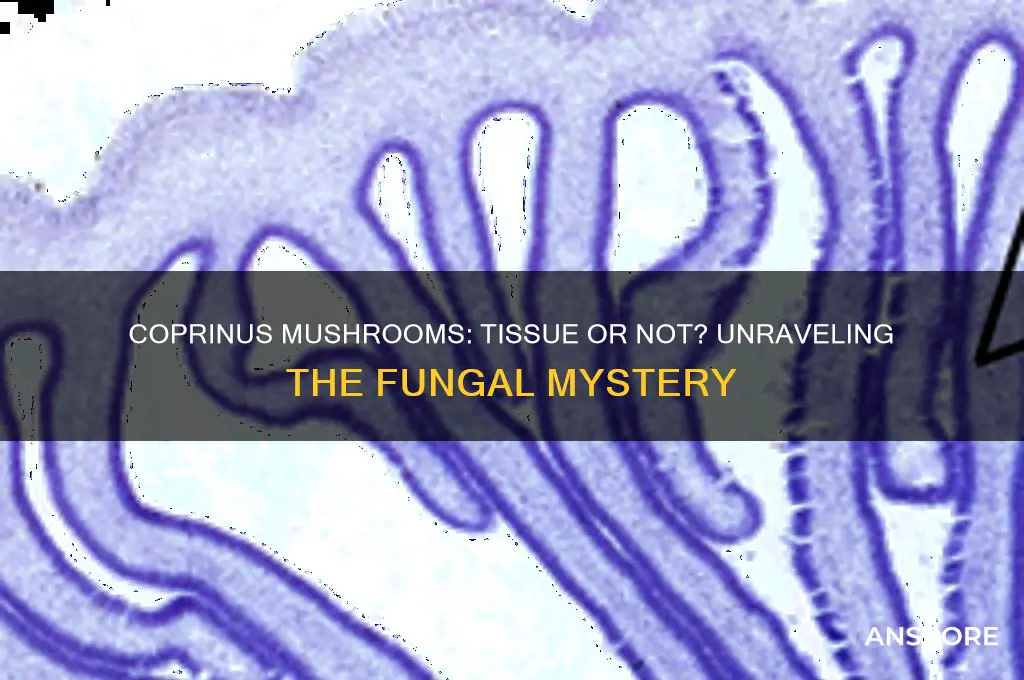

Coprinus mushrooms, commonly known as inky caps, exhibit a cellular composition that reflects their fungal nature and ecological role. Unlike plants and animals, fungi like Coprinus are composed of eukaryotic cells with distinct features. The primary cell type in Coprinus is the hyphal cell, which forms long, thread-like structures called hyphae. These hyphae are the building blocks of the mushroom's tissue and are organized into a network called the mycelium. The hyphal cells are characterized by their tubular shape, flexible cell walls composed of chitin, and the presence of septa (cross-walls) with pores that allow for the flow of cytoplasm and organelles between cells. This arrangement facilitates nutrient absorption and distribution throughout the organism.

Within the fruiting body of Coprinus mushrooms, different cell types and arrangements are observed. The pileus (cap) and stipe (stem) are primarily composed of densely packed hyphae, which provide structural support. In the gills (lamellae) beneath the cap, basidia—specialized reproductive cells—are prominently found. Basidia are club-shaped cells that produce spores, the fungal equivalent of seeds. Each basidium typically bears four spores, which are externally released and dispersed to propagate the species. The arrangement of basidia on the gills is crucial for efficient spore dispersal, a key aspect of Coprinus' life cycle.

Another important cell type in Coprinus is the parenchymatous cell, found in the trama (fleshy tissue) of the mushroom. These cells are thinner-walled and less specialized than hyphae, contributing to the overall structure and nutrient storage. In Coprinus, the rapid autolysis (self-digestion) of the gills, a unique feature of this genus, is facilitated by the breakdown of parenchymatous and hyphal cells. This process, known as deliquescence, is mediated by enzymes within the cells and highlights the dynamic nature of Coprinus' cellular composition.

The cellular arrangement in Coprinus mushrooms is highly organized to support their functions. Hyphae in the mycelium grow extensively in the substrate, absorbing nutrients through their cell walls. In the fruiting body, hyphae differentiate into specific structures like gills and the cap, demonstrating plasticity in cell arrangement. The septate hyphae allow for compartmentalization, preventing the spread of damage or infection throughout the organism. This modularity is a key adaptation that contributes to the resilience of Coprinus in its environment.

In summary, the cellular composition of Coprinus mushrooms is characterized by hyphal cells, basidia, and parenchymatous cells, each playing distinct roles in structure, reproduction, and nutrient management. The arrangement of these cells into hyphae, mycelium, and specialized fruiting body structures underscores the tissue-like organization of Coprinus, despite fungi not possessing true tissues as seen in plants or animals. Analyzing these cell types and their organization provides insights into the unique biology and ecological significance of Coprinus mushrooms.

Mushrooms: Are They Legal or Not?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$47.45

Tissue vs. non-tissue debate: Discusses whether Coprinus mushrooms meet the criteria for being considered tissue

The debate surrounding whether Coprinus mushrooms qualify as tissue hinges on the fundamental definition and characteristics of biological tissues. In biology, tissue is defined as a group of connected cells that have a similar function and structure, working together as a unit to perform a specific task. Animal and plant tissues are prime examples, where cells are organized into layers or structures like epithelium, muscle, or xylem. Coprinus mushrooms, being fungi, present a unique case because their cellular organization differs significantly from that of plants and animals. Fungi are composed of thread-like structures called hyphae, which form a network known as the mycelium. While this network is complex and functional, it does not align with the traditional layered or structured arrangement seen in animal or plant tissues. This raises the question: does the mycelial network of Coprinus mushrooms meet the criteria for being considered tissue?

One argument in favor of classifying Coprinus mushrooms as tissue is their functional specialization. The mycelium performs essential roles such as nutrient absorption, growth, and reproduction, analogous to the functions of tissues in other organisms. Additionally, the hyphae are interconnected, forming a cohesive system that operates as a unified entity, similar to how cells in tissues work together. However, critics argue that the lack of distinct layers or differentiated cell types in the mycelium sets it apart from traditional tissues. Unlike epithelial or muscular tissues, which have clear structural hierarchies, the mycelium of Coprinus mushrooms appears more homogeneous, with less obvious specialization at the cellular level. This distinction challenges the direct application of the tissue concept to fungi.

Another point of contention is the cellular composition and organization. Tissues typically consist of eukaryotic cells with specific shapes and arrangements tailored to their function. In Coprinus mushrooms, the hyphae are elongated, tubular cells with septa (cross-walls) that allow for compartmentalization but lack the diversity in cell types seen in tissues. Furthermore, the mycelium’s growth pattern is more diffuse and less structured compared to the organized layers of plant or animal tissues. Proponents of the tissue classification might argue that the mycelium’s functional integration compensates for its structural differences, while opponents emphasize that these differences are too significant to ignore.

From an evolutionary perspective, the tissue vs. non-tissue debate also considers the origins and adaptations of fungi. Fungi evolved independently from plants and animals, developing unique structures like hyphae and mycelia to thrive in their ecological niches. While these structures serve tissue-like functions, they arose through distinct evolutionary pathways. This raises the question of whether the tissue concept, originally defined for plants and animals, can be universally applied to fungi. Some biologists suggest that fungi represent an alternative form of multicellularity, one that does not fit neatly into the tissue framework but is equally sophisticated and functional.

In conclusion, the debate over whether Coprinus mushrooms are part of a tissue highlights the complexities of biological classification. While the mycelium of Coprinus mushrooms exhibits tissue-like functions and integration, its structural and organizational differences challenge its inclusion under the traditional tissue definition. This discussion underscores the need for a more inclusive and nuanced understanding of multicellular organization across diverse life forms. Whether Coprinus mushrooms are ultimately classified as tissue or not, their unique biology offers valuable insights into the diversity of life’s structural and functional strategies.

Identifying Oyster Mushroom Spore Times

You may want to see also

Comparative fungal tissue analysis: Compares Coprinus tissue structure with other mushroom species

The question of whether Coprinus mushrooms are part of a tissue necessitates a comparative analysis of their tissue structure with other mushroom species. Fungal tissues, unlike animal or plant tissues, are composed primarily of hyphae, which are filamentous structures forming the mycelium. In Coprinus spp., such as *Coprinus comatus* (shaggy mane), the tissue organization is characterized by a loosely arranged hyphal network with thin-walled, septate hyphae. This contrasts with the denser, more compact hyphal arrangement found in basidiocarp tissues of Agaricus bisporus (button mushroom), where thicker-walled hyphae provide structural rigidity. The comparative analysis reveals that while both species exhibit septate hyphae, the wall thickness and hyphal density contribute to differences in tissue resilience and growth form.

A key aspect of comparative fungal tissue analysis is the examination of fruiting body development. Coprinus mushrooms are known for their deliquescent gills, a feature linked to autolytic enzymes breaking down tissue during spore maturation. This tissue degradation is unique compared to non-deliquescent species like Pleurotus ostreatus (oyster mushroom), where gills remain intact post-maturity. The tissue composition in Coprinus, rich in hydrolytic enzymes, highlights a specialized adaptation for spore dispersal, contrasting with the more persistent tissue structures in other mushrooms. This comparison underscores the functional diversity of fungal tissues in relation to ecological roles.

Cellular organization within fungal tissues also varies significantly. In Coprinus, the hyphae are predominantly monomitic, consisting of generative cells. In contrast, species like Trametes versicolor (turkey tail) exhibit dimitic or trimitic tissues, incorporating skeletal and binding hyphae for enhanced structural support. This comparative analysis demonstrates that Coprinus tissues prioritize rapid growth and ephemeral structures, whereas other species invest in durable tissues for long-term survival. Such differences are critical in understanding tissue function and evolutionary adaptations in fungi.

Another critical factor in comparative analysis is the role of tissue composition in nutrient uptake and transport. Coprinus mycelium tissues are optimized for rapid substrate colonization, with thin-walled hyphae facilitating efficient nutrient absorption. In contrast, mycorrhizal fungi like Amanita muscaria (fly agaric) develop complex tissue interfaces with plant roots, featuring Hartig net structures for symbiotic nutrient exchange. This comparison highlights how tissue specialization in Coprinus aligns with saprotrophic lifestyles, while other species evolve tissues for mutualistic interactions.

Finally, the comparative study of fungal tissues must consider environmental responses. Coprinus tissues exhibit rapid degradation under stress, a trait linked to their short-lived fruiting bodies. In contrast, species like Schizophyllum commune (split gill) develop resilient tissues capable of withstanding desiccation. This analysis reveals that Coprinus tissues are part of a broader fungal tissue spectrum, where structural and biochemical properties are tailored to specific ecological niches. Understanding these differences is essential for advancing fungal biology and biotechnological applications.

Chinese Takeout: Mushroom Delights to Try

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, Coprinus mushrooms are not part of a tissue; they are individual fungi organisms.

No, Coprinus mushrooms are multicellular fungi and do not belong to any animal or plant tissue system.

No, the structure of Coprinus mushrooms, composed of hyphae and fruiting bodies, is distinct from plant or animal tissues.

No, Coprinus mushrooms are complete fungi organisms, not a type of tissue; their body is called mycelium, which is a network of hyphae.

No, parts of Coprinus mushrooms (like caps, gills, or stems) are not classified as tissue; they are fungal structures.