The death cap mushroom, scientifically known as *Amanita phalloides*, is one of the most toxic fungi in the world, responsible for the majority of fatal mushroom poisonings globally. Despite its unassuming appearance, this mushroom contains potent toxins, including amatoxins, which can cause severe liver and kidney damage, often leading to organ failure and death if ingested. Commonly found in Europe, North America, and other parts of the world, the death cap resembles edible mushrooms, making it particularly dangerous for foragers who mistake it for harmless varieties. Symptoms of poisoning typically appear 6 to 24 hours after consumption, starting with gastrointestinal distress and progressing to life-threatening complications if left untreated. Awareness and accurate identification are crucial to avoiding this deadly fungus.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Scientific Name | Amanita phalloides |

| Common Name | Death Cap Mushroom |

| Toxicity Level | Extremely Poisonous |

| Toxins Present | Amatoxins (e.g., α-Amanitin, β-Amanitin) |

| Symptoms of Poisoning | Initial: Gastrointestinal (vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain); Later: Liver and kidney failure, jaundice, seizures, coma |

| Onset of Symptoms | 6–24 hours after ingestion |

| Fatality Rate | 10–50% without treatment; higher without liver transplant |

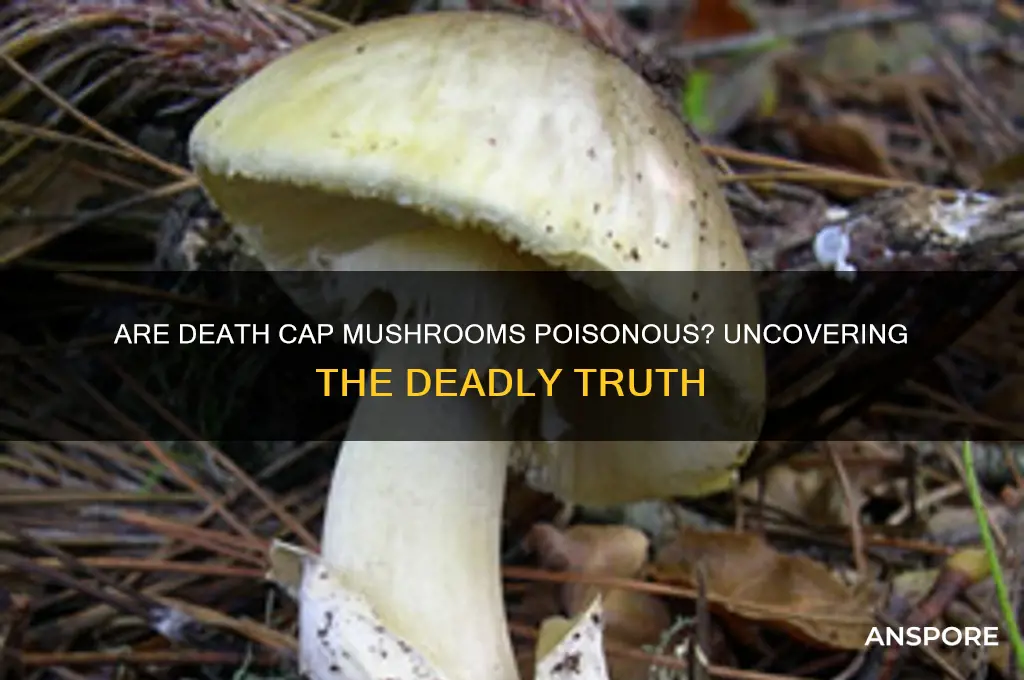

| Appearance | Olive-green to yellowish-green cap, white gills, bulbous base with volva |

| Habitat | Often found near oak, beech, and pine trees in Europe, North America, and other regions |

| Edible Lookalikes | Young Amanita phalloides can resemble edible mushrooms like Agaricus species (e.g., button mushrooms) |

| Treatment | Immediate medical attention, activated charcoal, supportive care, liver transplant in severe cases |

| Prevention | Avoid foraging without expert knowledge; always cook mushrooms thoroughly (though cooking does not detoxify death caps) |

| Historical Significance | Responsible for numerous fatal poisonings worldwide, including notable cases like the death of Roman Emperor Claudius (allegedly) |

| Detection | No simple field test; requires laboratory analysis for toxin confirmation |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Toxicity Levels: Death caps contain amatoxins, causing severe liver, kidney damage, often fatal if untreated

- Symptoms of Poisoning: Delayed onset (6-24 hours), includes vomiting, diarrhea, dehydration, organ failure

- Misidentification Risks: Resembles edible mushrooms like paddy straw, leading to accidental ingestion

- Treatment Options: Immediate medical care, activated charcoal, liver transplant in severe cases

- Geographic Distribution: Found in Europe, North America, Australia, often near oak, beech trees

Toxicity Levels: Death caps contain amatoxins, causing severe liver, kidney damage, often fatal if untreated

Death cap mushrooms, scientifically known as *Amanita phalloides*, are notorious for their extreme toxicity, primarily due to the presence of amatoxins. These toxins are cyclic octapeptides that evade digestion, allowing them to enter the bloodstream and wreak havoc on internal organs. Amatoxins are not destroyed by cooking, drying, or freezing, making death caps dangerous regardless of preparation. A single mushroom contains enough toxin to kill an adult, with as little as 30 grams (approximately half a cap) posing a severe threat. This lethal potential underscores the critical need for accurate identification and avoidance in the wild.

The toxicity of death caps manifests through their devastating impact on the liver and kidneys. Amatoxins target hepatocytes, the primary liver cells, disrupting protein synthesis and causing rapid cell death. Symptoms often appear 6–24 hours after ingestion, beginning with gastrointestinal distress (vomiting, diarrhea) that can misleadingly suggest a benign food poisoning. However, this is followed by a more severe phase 24–48 hours later, characterized by liver and kidney failure, jaundice, seizures, and coma. Without immediate medical intervention, the mortality rate exceeds 50%, even in otherwise healthy individuals. Children are particularly vulnerable due to their lower body mass, with smaller doses proving fatal.

Treatment for death cap poisoning is a race against time, emphasizing the importance of early detection. Gastric decontamination (activated charcoal or lavage) is effective only if administered within hours of ingestion. Silibinin, a milk thistle extract, is the primary antidote, acting as a liver protectant by inhibiting amatoxin uptake. In severe cases, liver transplantation may be necessary, though this is not always feasible due to the rapid progression of organ failure. Survival often hinges on prompt recognition of symptoms and access to specialized medical care, highlighting the need for public awareness and education.

Practical precautions are essential for anyone foraging wild mushrooms. Death caps resemble edible species like the straw mushroom (*Volvariella volvacea*) and young puffballs, increasing the risk of accidental ingestion. Key identifiers include a greenish-yellow cap, white gills, and a volva (cup-like base). However, reliance on morphology alone is risky, as variations exist. If uncertain, avoid consumption entirely. Foragers should carry a field guide, consult experts, and never taste or smell mushrooms for identification. In case of suspected poisoning, immediately contact emergency services or a poison control center, providing details of the mushroom’s appearance and time of ingestion. Time is critical—delaying treatment reduces survival odds exponentially.

Are Black Trumpet Mushrooms Poisonous? Unveiling the Truth About This Wild Fungus

You may want to see also

Symptoms of Poisoning: Delayed onset (6-24 hours), includes vomiting, diarrhea, dehydration, organ failure

The insidious danger of death cap mushrooms lies not only in their toxicity but in the deceptive delay of symptoms. Unlike many poisons that act swiftly, the amatoxins in these mushrooms take their time, often 6 to 24 hours, to reveal their deadly effects. This delay can be particularly treacherous, as it may lead victims to believe they’ve escaped harm, only to be blindsided by severe symptoms later. Understanding this timeline is crucial for anyone who suspects ingestion, as immediate medical intervention can mean the difference between life and death.

Once the symptoms do appear, they are relentless and unforgiving. Vomiting and diarrhea are the body’s initial attempts to expel the toxin, but these reactions often lead to rapid dehydration, compounding the danger. For children, the elderly, or those with pre-existing health conditions, dehydration can escalate quickly, requiring urgent rehydration strategies such as oral electrolyte solutions or, in severe cases, intravenous fluids. However, rehydration alone is not enough; the toxin’s primary target is the liver, and organ failure can follow within 48 to 72 hours without treatment.

The progression from gastrointestinal distress to organ failure underscores the importance of recognizing the delayed onset of symptoms. A single death cap mushroom contains enough amatoxins to kill an adult, but even a small bite can be lethal. If ingestion is suspected, time is of the essence. Activated charcoal, administered within the first hour, can help bind the toxin in the stomach, but its effectiveness diminishes rapidly. Beyond this window, medical professionals may use silibinin, a compound derived from milk thistle, to protect liver cells, alongside supportive care like dialysis for kidney failure.

Comparing the symptoms of death cap poisoning to those of other mushroom toxicities highlights its unique severity. While some mushrooms cause immediate gastrointestinal upset, the delayed onset and systemic damage of amatoxin poisoning set it apart. This distinction is vital for foragers and healthcare providers alike, as misdiagnosis can lead to fatal delays in treatment. Education and awareness are key—knowing the symptoms and acting swiftly can save lives. Always remember: when in doubt, seek medical help immediately, even if symptoms haven’t yet appeared.

Is Psilocybin Poisonous? Debunking Myths About Magic Mushrooms

You may want to see also

Misidentification Risks: Resembles edible mushrooms like paddy straw, leading to accidental ingestion

The death cap mushroom, *Amanita phalloides*, is a silent assassin in the forest, often mistaken for its benign cousin, the paddy straw mushroom (*Volvariella volvacea*). This misidentification is not merely a trivial error—it can be fatal. Both mushrooms share a similar cap color and size, and the death cap’s volva (a cup-like structure at the base) can resemble the paddy straw’s delicate veil remnants. Foragers, especially those unfamiliar with mycology, may overlook critical differences, such as the death cap’s greenish gills or persistent ring on the stem. A single death cap contains enough amatoxins to cause severe liver and kidney failure in an adult, with symptoms appearing 6–24 hours after ingestion, often too late for effective intervention.

To avoid this deadly mistake, follow a systematic identification process. First, examine the mushroom’s gills—paddy straw mushrooms have pinkish gills that turn brown with age, while death caps have white to greenish gills. Second, check the stem—paddy straw mushrooms lack a ring, whereas death caps have a distinct, skirt-like ring. Third, inspect the base—paddy straw mushrooms grow in clusters on paddy straw or wood chips, while death caps often have a bulbous, sack-like volva at the base. If in doubt, discard the mushroom entirely. Remember, no meal is worth risking your life.

The persuasive argument here is clear: education and caution are paramount. Foraging without proper knowledge is akin to playing Russian roulette with nature. Workshops, field guides, and expert-led mushroom hunts can equip foragers with the skills to distinguish between species. Apps and online resources, while helpful, should never replace hands-on learning. For families, teaching children to avoid touching or tasting wild mushrooms is critical, as even a small bite of a death cap can be lethal to a child. The takeaway is simple: when in doubt, throw it out.

Comparatively, the misidentification risk of death caps is not unique but is particularly insidious due to their striking resemblance to edible varieties. Unlike other toxic mushrooms, such as the fly agaric (*Amanita muscaria*), which has a distinct red cap with white spots, the death cap’s unassuming appearance makes it a hidden danger. Its ability to thrive in urban areas, such as parks and gardens, further increases the likelihood of accidental ingestion. Unlike paddy straw mushrooms, which are cultivated and sold commercially, death caps are exclusively wild, yet their presence near human habitats amplifies the risk. This juxtaposition of accessibility and danger underscores the need for heightened awareness.

Descriptively, the death cap’s allure lies in its deceptive beauty. Its smooth, olive-green to yellowish cap, often tinged with brown, can appear innocuous, even inviting. Its robust stem and volva give it an almost regal presence, making it easy to mistake for a prized edible. However, this beauty masks a deadly payload. Amatoxins, the primary toxins in death caps, are heat-stable and cannot be neutralized by cooking. Even experienced foragers have fallen victim to its charms, highlighting the importance of meticulous identification. The lesson is clear: nature’s most dangerous creations often hide behind a facade of harmlessness.

Spotting Deadly Fungi: A Guide to Identifying Poisonous Mushrooms Safely

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Treatment Options: Immediate medical care, activated charcoal, liver transplant in severe cases

Death cap mushrooms, scientifically known as *Amanita phalloides*, are notoriously toxic, containing amatoxins that can cause severe liver damage and, if untreated, death. If ingestion is suspected, immediate medical care is non-negotiable. Time is critical; symptoms like nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea may appear 6–24 hours after consumption, but by then, toxins are already at work. Hospitals will likely administer intravenous fluids to stabilize hydration and electrolytes, and gastric lavage (stomach pumping) may be performed if the patient presents within hours of ingestion. Delaying treatment increases the risk of irreversible liver damage, making swift action essential.

Once in medical care, activated charcoal may be administered to bind residual toxins in the gastrointestinal tract and prevent further absorption. While not a cure, it serves as a crucial adjunct therapy. The typical adult dose is 50–100 grams, mixed with water, given within 1–2 hours of ingestion for maximum effectiveness. However, its utility diminines significantly after 4–6 hours, underscoring the urgency of early intervention. Children and the elderly may require adjusted dosages, emphasizing the need for professional oversight.

In severe cases, where amatoxins have caused critical liver failure, a liver transplant may be the only life-saving option. This drastic measure is reserved for patients with acute liver necrosis, coagulopathy, or hepatic encephalopathy. The decision to transplant is complex, balancing the risks of surgery with the inevitability of organ failure. Notably, some patients may require temporary liver support systems, such as MARS therapy, while awaiting a donor organ. Survival rates post-transplant are encouraging, but the procedure is not without long-term complications, including immunosuppression and rejection risks.

Comparatively, while treatments like silibinin (milk thistle extract) and N-acetylcysteine have shown promise in reducing liver damage, they are adjunctive and not substitutes for the above interventions. The key takeaway is that death cap poisoning demands a tiered approach: immediate medical stabilization, toxin mitigation with activated charcoal, and, in dire cases, liver transplantation. Public awareness and rapid response remain the most effective tools in combating this silent killer.

Are California Mushrooms Poisonous? A Guide to Safe Foraging

You may want to see also

Geographic Distribution: Found in Europe, North America, Australia, often near oak, beech trees

The death cap mushroom, *Amanita phalloides*, thrives in temperate regions across Europe, North America, and Australia, often forming symbiotic relationships with oak and beech trees. This mycorrhizal association allows the fungus to extract nutrients from the soil while aiding the tree’s root system, creating a mutually beneficial partnership. For foragers, this ecological link is critical: spotting these trees in wooded areas should immediately raise caution, as death caps frequently appear at their bases or nearby. Understanding this habitat preference is the first step in avoiding accidental poisoning, particularly during autumn when fruiting bodies are most visible.

Geographically, the death cap’s spread aligns with human migration and trade. Originally native to Europe, it has naturalized in regions like California and Australia through the importation of oak and beech saplings, often with soil containing its spores. This unintentional introduction highlights how human activity can disrupt ecosystems, turning a local hazard into a global one. In California, for instance, death caps are now commonly found in residential areas with ornamental oak trees, posing risks to children and pets who may mistake them for edible species.

Foraging safely in these regions requires vigilance and knowledge. Death caps resemble edible mushrooms like straw mushrooms (*Volvariella volvacea*) or young puffballs, but key identifiers include a bulbous base, greenish cap, and white gills. However, relying solely on visual cues is risky; even experienced foragers have been poisoned. A practical tip: carry a field guide specific to your region and use a knife to examine the mushroom’s base and gills before collecting. If in doubt, discard it—no meal is worth the risk of ingesting amatoxins, which can cause liver failure within 48 hours.

Comparatively, the death cap’s distribution contrasts with other toxic fungi, such as the destroying angel (*Amanita bisporigera*), which is primarily found in North America. While both are deadly, their geographic ranges limit exposure for certain populations. However, the death cap’s broader reach, combined with its ability to thrive in urban and suburban areas, makes it a more pervasive threat. For travelers or immigrants unfamiliar with local fungi, education is key: workshops or apps like iNaturalist can help identify species, but always consult a mycologist when uncertain.

Finally, prevention is paramount. In regions where death caps are endemic, public health campaigns should emphasize their danger, particularly targeting gardeners, hikers, and immigrant communities who may recognize similar-looking mushrooms from their home countries. Schools and community centers can play a role by incorporating mushroom safety into environmental education programs. For households, keep the Poison Control hotline number (1-800-222-1222 in the U.S.) readily accessible, as prompt treatment—often involving activated charcoal and liver transplants in severe cases—can be life-saving. Awareness of the death cap’s habitat and distribution is not just academic; it’s a practical tool for survival.

Are Toadstools Poisonous? Unveiling the Truth About Fungal Toxicity

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, death cap mushrooms (Amanita phalloides) are extremely poisonous and can be fatal if ingested.

Symptoms include severe abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, dehydration, liver and kidney failure, and potentially death within days if untreated.

Symptoms typically appear 6–24 hours after ingestion, making it initially seem harmless, but the toxins cause severe damage later.

No, cooking, drying, or boiling does not eliminate the toxins in death cap mushrooms; they remain deadly even after preparation.

Only consume mushrooms that are positively identified by an expert, avoid foraging unless highly knowledgeable, and never eat wild mushrooms unless certain of their safety.