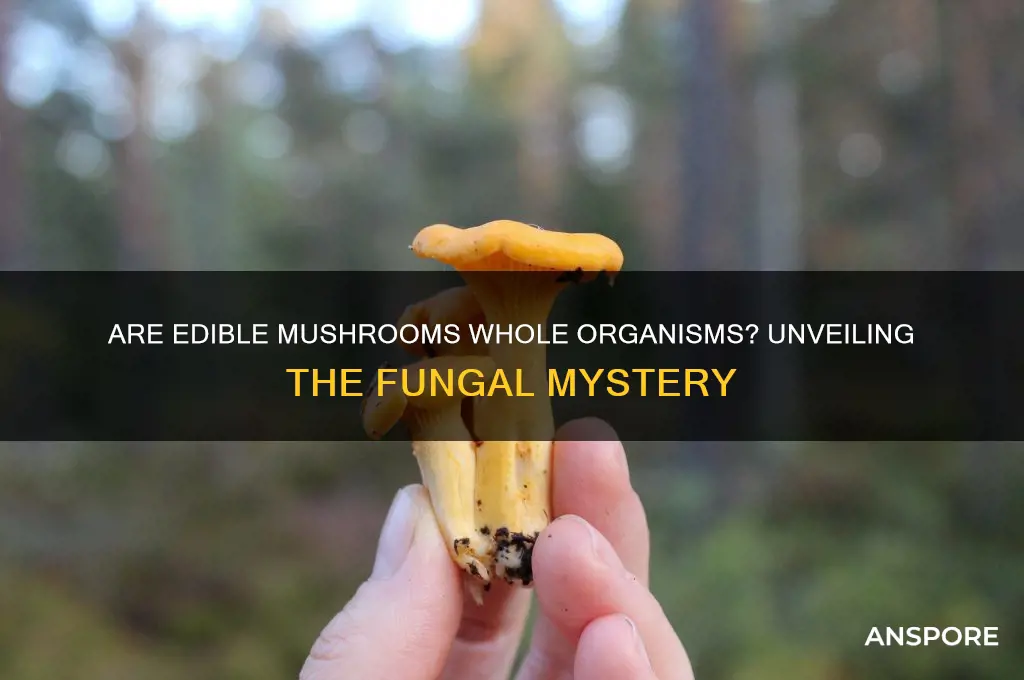

Edible mushrooms, often perceived as simple fungi, are indeed whole organisms, belonging to the kingdom Fungi, distinct from plants and animals. Unlike plants, they lack chlorophyll and do not perform photosynthesis, instead obtaining nutrients by decomposing organic matter. A mushroom is the fruiting body of a fungus, which emerges above ground to release spores for reproduction, while the bulk of the organism lies beneath the surface as a network of thread-like structures called mycelium. This mycelium is the primary body of the fungus, responsible for nutrient absorption and growth. Therefore, when we consume edible mushrooms, we are eating a part of a complex, multicellular organism that plays a vital role in ecosystems as decomposers and symbionts.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Edible mushrooms are the fruiting bodies of fungi, which are eukaryotic organisms. |

| Organism Type | Fungi (Kingdom: Fungi) |

| Whole Organism | No, the mushroom is only the reproductive structure (fruiting body) of the fungus. The main body (mycelium) remains underground or in substrate. |

| Function of Mushroom | Produces and disperses spores for reproduction. |

| Mycelium | The vegetative part of the fungus, consisting of a network of thread-like structures called hyphae, which absorbs nutrients. |

| Visibility | Mushrooms are visible above ground, while mycelium is typically hidden. |

| Role in Ecosystem | Decomposers, recyclers of organic matter, and symbiotic partners with plants (e.g., mycorrhizal fungi). |

| Edibility | Only specific mushroom species are edible; many are toxic or inedible. |

| Nutritional Value | Rich in protein, vitamins (B, D), minerals (selenium, potassium), and antioxidants. |

| Examples of Edible Mushrooms | Button, shiitake, oyster, portobello, chanterelle, porcini. |

| Misconception | Mushrooms are often mistakenly considered plants, but they are a separate kingdom of life. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Mycelium vs. Fruiting Body: Understanding the mushroom's life cycle and its edible parts

- Nutritional Composition: Analyzing vitamins, minerals, and proteins in edible mushrooms

- Toxic Look-Alikes: Identifying poisonous species that resemble edible mushrooms

- Cultivation Methods: Techniques for growing whole, safe, edible mushrooms at home

- Ecological Role: How mushrooms contribute to ecosystems as decomposers and symbionts

Mycelium vs. Fruiting Body: Understanding the mushroom's life cycle and its edible parts

Mushrooms, often perceived as singular entities, are merely the visible tip of a complex biological iceberg. The fruiting body—what we commonly recognize as a mushroom—is just one phase in the life cycle of a fungus. Beneath the surface lies the mycelium, a network of thread-like structures called hyphae, which constitutes the organism’s primary form. This distinction is crucial for understanding what parts of a mushroom are edible and why. While the fruiting body is the part typically consumed, the mycelium plays a vital role in nutrient absorption and growth, though it is rarely eaten directly.

Consider the analogy of an apple tree: the tree itself (mycelium) sustains life and produces apples (fruiting bodies) seasonally. Just as we eat the fruit, not the tree, we consume the mushroom’s fruiting body, not its mycelium. However, the mycelium’s health directly impacts the fruiting body’s quality. For instance, mycelium grown in nutrient-rich substrates can yield more robust, flavorful mushrooms. This relationship highlights why cultivators focus on optimizing mycelium growth, even though it’s the fruiting body that ends up on our plates.

From a nutritional standpoint, the fruiting body is the star. It contains higher concentrations of bioactive compounds like beta-glucans, antioxidants, and vitamins compared to mycelium. For example, a 100-gram serving of shiitake mushroom caps provides approximately 3.1 grams of protein and 121 mg of ergothioneine, a potent antioxidant. In contrast, mycelium-based supplements, often grown on grain, may contain lower levels of these compounds due to the substrate’s dilution effect. Thus, while mycelium is essential for the fungus’s survival, the fruiting body is the more nutrient-dense choice for consumption.

Foraging enthusiasts must also understand this distinction for safety. The fruiting body’s visibility makes it easier to identify, but misidentification can be fatal. Mycelium, being subterranean, is less accessible and less likely to be confused with toxic species. However, consuming wild mushrooms without proper knowledge of their life cycle and growth conditions can lead to poisoning. For instance, mushrooms growing in polluted soil may accumulate toxins in their fruiting bodies, while the mycelium remains unaffected. Always consult a field guide or expert when foraging, and focus on the fruiting body’s characteristics for accurate identification.

In cultivation, the mycelium’s role is indispensable. It can be propagated through techniques like spore inoculation or tissue culture, allowing growers to produce consistent, high-quality fruiting bodies. For home growers, maintaining sterile conditions during mycelium colonization is critical to prevent contamination. Once established, the mycelium will fruit under the right environmental triggers—humidity, temperature, and light. This process underscores the symbiotic relationship between mycelium and fruiting body, where one cannot thrive without the other.

In summary, while the fruiting body is the edible, nutrient-rich part of a mushroom, the mycelium is its lifeblood. Understanding this duality not only enhances culinary and nutritional choices but also ensures safer foraging and more successful cultivation. Whether you’re a chef, forager, or grower, recognizing the roles of mycelium and fruiting body in a mushroom’s life cycle is key to appreciating these fascinating organisms in their entirety.

Are All Psilocybe Mushrooms Edible? Safety and Risks Explained

You may want to see also

Nutritional Composition: Analyzing vitamins, minerals, and proteins in edible mushrooms

Edible mushrooms are not just culinary delights; they are nutritional powerhouses, offering a unique blend of vitamins, minerals, and proteins that set them apart from other plant-based foods. Unlike plants, mushrooms are fungi, and their nutritional profile reflects their distinct biological role as decomposers. This uniqueness raises the question: how do their nutrient contents contribute to human health, and what makes them a valuable addition to our diets?

Analyzing their vitamin content reveals a standout feature: mushrooms are one of the few non-animal sources of vitamin D, a nutrient critical for bone health and immune function. When exposed to ultraviolet light, mushrooms naturally produce vitamin D2, offering up to 200 IU per 100 grams in varieties like maitake and portobello. This is particularly beneficial for vegans and those with limited sun exposure. Additionally, mushrooms are rich in B vitamins, especially riboflavin (B2), niacin (B3), and pantothenic acid (B5), which support energy metabolism and skin health. For instance, a 100-gram serving of shiitake mushrooms provides 25% of the daily recommended intake of B5.

Minerals in mushrooms further enhance their nutritional value. They are excellent sources of selenium, a potent antioxidant that supports thyroid function and reduces oxidative stress. A single cup of crimini mushrooms contains approximately 12 mcg of selenium, nearly 20% of the daily requirement. Mushrooms also boast high levels of potassium, copper, and phosphorus, essential for heart health, red blood cell formation, and bone strength. Notably, their low sodium content makes them an ideal food for managing blood pressure.

Protein is another area where mushrooms shine, especially for plant-based diets. While not as protein-dense as animal products, mushrooms offer a complete amino acid profile in some varieties, such as oyster mushrooms, which contain 3 grams of protein per 100 grams. This makes them a valuable meat alternative, particularly when combined with other plant proteins like legumes. For example, pairing mushroom-based dishes with lentils or quinoa ensures a balanced intake of essential amino acids.

Incorporating mushrooms into your diet is simple and versatile. Sautéing, grilling, or adding them to soups and stir-fries preserves their nutrients while enhancing flavor. For vitamin D optimization, choose UV-exposed varieties or expose fresh mushrooms to sunlight for 15–30 minutes before cooking. For those monitoring mineral intake, combining mushrooms with vitamin C-rich foods like bell peppers or citrus enhances iron absorption, as mushrooms contain non-heme iron. Whether you’re a health enthusiast or simply seeking variety, mushrooms offer a nutrient-dense option that complements any meal plan.

Are Earthball Mushrooms Edible? A Guide to Safety and Identification

You may want to see also

Toxic Look-Alikes: Identifying poisonous species that resemble edible mushrooms

Edible mushrooms, despite their culinary allure, are not whole organisms in the way animals or plants are. They are the fruiting bodies of fungi, which primarily consist of a vast underground network called mycelium. This distinction is crucial when considering the dangers of toxic look-alikes, as misidentification can lead to severe poisoning or even death. For instance, the deadly Amanita phalloides, or Death Cap, closely resembles the edible Paddy Straw mushroom (Volvariella volvacea), but contains amatoxins that can cause liver failure within 24–48 hours after ingestion. Even a small bite—as little as 50 grams—can be fatal if left untreated.

To avoid such peril, foragers must adopt a meticulous approach. Start by learning the key features of both edible and poisonous species. For example, the Death Cap often has a volva (a cup-like structure at the base) and a skirt-like ring on the stem, whereas the Paddy Straw mushroom lacks these features. Always carry a reliable field guide or use a trusted mushroom identification app, but never rely solely on digital tools. Physical characteristics like spore color, gill attachment, and smell can be decisive identifiers. For instance, the toxic Galerina marginata, a look-alike of the edible Honey Mushroom (Armillaria mellea), has a rusty brown spore print, while the Honey Mushroom’s spores are white.

A critical caution is to never consume a mushroom based on a single identifying feature. Some toxic species, like the Destroying Angel (Amanita bisporigera), share multiple traits with edible varieties but contain lethal toxins. Always cross-reference multiple characteristics and, when in doubt, consult an expert. Cooking or boiling does not neutralize most mushroom toxins, so proper identification is non-negotiable. For beginners, it’s advisable to forage with an experienced guide or join a mycological society to gain hands-on knowledge.

Finally, understanding the habitat can provide additional clues. Toxic species often thrive in specific environments. For example, the Death Cap is commonly found near oak trees, while edible Chanterelles (Cantharellus cibarius) prefer coniferous or mixed forests. However, habitat alone is not a foolproof identifier. Always prioritize morphological traits and, if possible, perform a spore print test. Remember, the goal is not just to find edible mushrooms but to exclude the deadly ones. Misidentification is a risk no forager can afford.

Are Shaggy Mane Mushrooms Edible? A Forager's Guide to Safety

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Cultivation Methods: Techniques for growing whole, safe, edible mushrooms at home

Edible mushrooms, unlike single-celled organisms, are indeed whole organisms composed of a network of thread-like structures called mycelium, which eventually forms the fruiting body we recognize as a mushroom. Growing these whole organisms at home requires understanding their unique biology and creating an environment that mimics their natural habitat. Here’s how to cultivate safe, edible mushrooms using proven techniques.

Step 1: Choose the Right Mushroom Species

Not all mushrooms are created equal. For beginners, oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) are ideal due to their fast growth (2–3 weeks) and tolerance for minor environmental fluctuations. Shiitake (*Lentinula edodes*) and lion’s mane (*Hericium erinaceus*) are also popular but require more precise conditions. Avoid wild spores unless you’re an experienced mycologist, as misidentification can lead to toxic varieties. Purchase certified spawn (mycelium-inoculated substrate) from reputable suppliers to ensure safety.

Step 2: Prepare the Growing Medium

Mushrooms thrive on organic matter. For oyster mushrooms, pasteurize straw by soaking it in 160°F (71°C) water for 1–2 hours, then drain and cool. Mix the spawn into the straw at a ratio of 1:10 (spawn to substrate). For shiitake, hardwood sawdust or logs are preferred. Sterilize sawdust in a pressure cooker at 15 psi for 1.5 hours to eliminate competitors. Inoculate with spawn and seal in autoclavable bags. Proper substrate preparation is critical to prevent contamination by molds or bacteria.

Step 3: Control Environmental Conditions

Mushrooms require specific humidity (70–90%), temperature (60–75°F or 15–24°C), and indirect light. Use a humidifier or mist the growing area twice daily. Maintain airflow with a small fan to prevent mold. Fruiting initiates when mycelium colonizes the substrate, often signaled by a white, cobweb-like growth. Trigger fruiting by exposing the mycelium to cooler temperatures (55–60°F or 13–15°C) and higher humidity, simulating autumn conditions.

Cautions and Troubleshooting

Contamination is the primary risk. Sterilize all tools and work in a clean environment. If mold appears, remove the affected area immediately. Slow growth may indicate insufficient humidity or improper substrate preparation. If mushrooms deform or fail to fruit, adjust temperature or light exposure. Always wear gloves when handling substrates to avoid introducing pathogens.

Harvesting and Consumption

Harvest mushrooms when the caps are fully open but before the gills release spores. Twist gently at the base to avoid damaging the mycelium, allowing for multiple flushes. Cook mushrooms thoroughly to break down chitin, a hard-to-digest cell wall component. Store harvested mushrooms in paper bags in the refrigerator for up to a week. Growing mushrooms at home not only provides a sustainable food source but also deepens your connection to the fascinating world of fungi.

Are Pheasant Back Mushrooms Edible? A Comprehensive Guide to Safety

You may want to see also

Ecological Role: How mushrooms contribute to ecosystems as decomposers and symbionts

Mushrooms, often celebrated for their culinary versatility, are far more than just edible delights. They are the visible fruiting bodies of fungi, which play a pivotal role in ecosystem health. As decomposers, fungi break down dead organic matter, recycling nutrients back into the soil. This process is essential for maintaining soil fertility and supporting plant growth. Without fungi, forests and other ecosystems would be buried under layers of undecomposed material, stifling new life. For instance, the common oyster mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) excels at decomposing wood, turning fallen trees into nutrient-rich humus. This ability not only sustains the ecosystem but also highlights why mushrooms are integral to the natural world, not just our plates.

Beyond decomposition, mushrooms act as symbionts, forming mutualistic relationships with plants through mycorrhizal networks. These networks, often referred to as the "wood wide web," allow plants to exchange nutrients and signals, enhancing their resilience to stressors like drought or disease. For example, truffles (*Tuber* species) form mycorrhizal associations with tree roots, providing them with hard-to-reach nutrients like phosphorus in exchange for carbohydrates. This symbiotic relationship underscores the interconnectedness of life and demonstrates how mushrooms are not isolated organisms but rather key players in ecological harmony.

Consider the practical implications of these roles for gardeners and farmers. Incorporating mycorrhizal fungi into soil amendments can improve crop yields and reduce the need for synthetic fertilizers. A study found that inoculating soil with *Glomus intraradices* increased plant biomass by up to 30%. Similarly, using decomposer fungi like *Stropharia rugosoannulata* (wine cap mushrooms) in compost piles accelerates organic matter breakdown, producing richer soil in less time. These applications illustrate how understanding mushrooms’ ecological roles can directly benefit sustainable agriculture.

However, it’s crucial to approach these practices with caution. Not all fungi are beneficial; some can be pathogenic to plants or even toxic to humans. For instance, *Armillaria* species, while decomposers, can cause root rot in living trees. Always identify fungi accurately before introducing them to your ecosystem. Additionally, while edible mushrooms like chanterelles (*Cantharellus cibarius*) are safe for consumption, their wild counterparts may resemble poisonous species. Proper identification is paramount—a mistake could have severe consequences.

In conclusion, mushrooms are not just whole organisms in the sense of being complete life forms; they are whole in their ecological impact. Their roles as decomposers and symbionts are indispensable, shaping the health and productivity of ecosystems. By harnessing their abilities responsibly, we can foster more sustainable and resilient environments. Whether in the wild or in our gardens, mushrooms remind us of the intricate balance of nature and our role in preserving it.

Are Dead Man's Fingers Mushrooms Edible? A Safety Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, edible mushrooms are whole organisms. They are the fruiting bodies of fungi, which are multicellular eukaryotic organisms.

Mushrooms are composed of several parts, including the cap (pileus), gills or pores (hymenium), stem (stipe), and a network of thread-like structures called mycelium underground.

The part of the mushroom we eat (the fruiting body) is only a visible portion of the organism. The majority of the fungus exists as mycelium beneath the surface, which is not typically consumed.

Mushrooms are independent organisms that obtain nutrients by decomposing organic matter. However, some species form symbiotic relationships with plants (mycorrhizal fungi) or rely on specific conditions to grow.

Not all parts of a mushroom are edible. While the cap and stem are commonly consumed, other parts like the base of the stem or mycelium are often tough or unpalatable. Always identify mushrooms correctly before eating.