Endospores and fungal spores are both specialized structures produced by certain microorganisms, but they serve distinct purposes and exhibit different reproductive capabilities. Endospores, formed by some bacteria like *Clostridium* and *Bacillus*, are highly resistant, dormant forms that allow the organism to survive harsh environmental conditions. They are not reproductive structures themselves but rather a means of survival, as they can germinate into vegetative cells when conditions improve. In contrast, fungal spores are reproductive units produced by fungi, such as molds and yeasts, and are directly involved in reproduction and dispersal. Fungal spores can germinate under favorable conditions to grow into new fungal organisms, making them a key part of the fungal life cycle. Thus, while both structures are adaptive, only fungal spores are inherently reproductive, whereas endospores are primarily protective.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproductive Capability | Endospores: Not directly reproductive; they are dormant, resilient structures that can germinate into vegetative cells under favorable conditions. Fungal Spores: Directly reproductive; they can germinate and grow into new fungal organisms. |

| Origin | Endospores: Formed within bacterial cells (primarily in Gram-positive bacteria) as a survival mechanism. Fungal Spores: Produced externally or internally by fungal organisms as part of their reproductive cycle. |

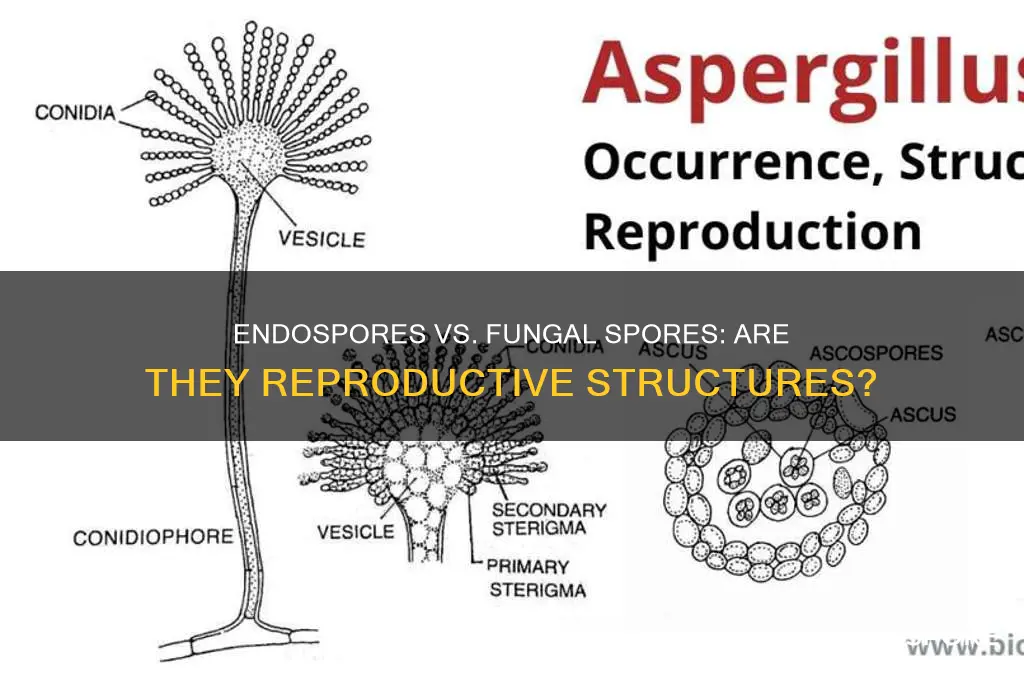

| Structure | Endospores: Single-celled, highly resistant, and contain DNA, RNA, and enzymes. Fungal Spores: Varied structures (e.g., conidia, asci, basidiospores) depending on the fungal species. |

| Resistance | Endospores: Extremely resistant to heat, radiation, desiccation, and chemicals. Fungal Spores: Generally less resistant than endospores but can survive harsh conditions depending on the type. |

| Function | Endospores: Primarily for survival in adverse environments. Fungal Spores: Primarily for reproduction and dispersal. |

| Location | Endospores: Formed inside the bacterial cell. Fungal Spores: Produced on specialized structures (e.g., hyphae, fruiting bodies) or directly on the fungus. |

| Germination | Endospores: Require specific triggers (e.g., nutrients, temperature) to germinate into vegetative cells. Fungal Spores: Germinate directly into hyphae or other fungal structures under suitable conditions. |

| Taxonomic Group | Endospores: Exclusive to certain bacteria (e.g., Bacillus, Clostridium). Fungal Spores: Found across diverse fungal groups (e.g., Ascomycetes, Basidiomycetes, Zygomycetes). |

| Dispersal | Endospores: Dispersed passively through environmental means. Fungal Spores: Actively or passively dispersed via air, water, or vectors. |

| Size | Endospores: Typically smaller (0.5–1.5 μm). Fungal Spores: Vary widely in size (e.g., 2–100 μm) depending on the species. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Endospore Formation Process

Endospores, unlike fungal spores, are not reproductive structures but rather dormant, highly resistant survival forms produced by certain bacteria, primarily within the Firmicute phylum. The endospore formation process, or sporulation, is a complex, multi-stage mechanism triggered by nutrient deprivation, particularly the lack of carbon and nitrogen sources. This process begins with the asymmetric division of the bacterial cell, forming a smaller forespore and a larger mother cell. The forespore is engulfed by the mother cell, which then synthesizes a multi-layered protective coat around it, including a cortex rich in peptidoglycan and a proteinaceous outer coat. This structure provides resistance to heat, radiation, desiccation, and chemicals, ensuring the endospore’s longevity in harsh environments.

The sporulation process is tightly regulated by a network of genes, primarily the *spo0A* operon, which activates in response to environmental stress. As the mother cell degrades its own DNA and cytoplasmic contents, it transfers nutrients and protective proteins to the developing endospore. This altruistic behavior ensures the endospore’s viability, even at the cost of the mother cell’s demise. Notably, the cortex layer is dehydrated during maturation, increasing the endospore’s mechanical strength and resistance. This stage is critical, as improperly formed spores may fail to withstand extreme conditions, rendering them non-viable.

Practical applications of understanding endospore formation include food safety and sterilization protocols. For instance, *Clostridium botulinum* endospores can survive boiling temperatures, necessitating pressure cooking at 121°C for 3 minutes to ensure destruction. In laboratory settings, sporulation assays are used to study bacterial stress responses and develop antimicrobial strategies. Researchers also explore genetic engineering of sporulation pathways to enhance endospore stability for biotechnological uses, such as vaccine delivery or environmental cleanup.

Comparatively, fungal spores are reproductive structures designed for dispersal and colonization, whereas endospores are purely survival mechanisms. This distinction is crucial in microbiology, as it influences how we address contamination and infection. For example, while fungal spores can be controlled with fungicides, endospores require more aggressive methods like autoclaving. Understanding the endospore formation process not only highlights bacterial adaptability but also informs strategies to combat spore-forming pathogens in clinical and industrial settings.

In summary, the endospore formation process is a remarkable example of bacterial resilience, involving asymmetric cell division, protective coat synthesis, and genetic regulation. Its unique characteristics differentiate it from fungal spores, emphasizing its role as a survival rather than reproductive structure. By studying this process, scientists can develop targeted interventions to manage spore-forming bacteria, ensuring safety in food, healthcare, and environmental contexts. Practical tips include using spore-specific sterilization techniques and monitoring nutrient levels in bacterial cultures to prevent sporulation in unwanted scenarios.

Exploring the Microscopic World: What Do Spores Really Look Like?

You may want to see also

Fungal Spore Germination Steps

Fungal spores are nature's tiny survivalists, capable of enduring harsh conditions until the right moment to sprout into new life. Unlike endospores, which are bacterial structures primarily for survival, fungal spores are reproductive units designed to disperse and germinate under favorable conditions. Understanding the steps of fungal spore germination is crucial for fields ranging from agriculture to medicine, as it reveals how fungi propagate and how we might control them.

Step 1: Dormancy Breaking

Fungal spores enter a dormant state to withstand adverse environments, such as extreme temperatures or nutrient scarcity. To initiate germination, dormancy must be broken. This often requires external triggers like water availability, specific temperature ranges (typically 20–30°C for common fungi), or exposure to light. For example, *Aspergillus* spores require moisture and warmth, while some plant pathogens like *Fusarium* respond to host-derived chemicals. Practical tip: To prevent fungal growth in stored grains, maintain humidity below 65% and temperatures under 15°C.

Step 2: Isotropic Growth and Metabolism Resumption

Once dormancy is broken, the spore absorbs water, swelling and reactivating metabolic processes. This phase, known as isotropic growth, involves the repair of cellular components and the synthesis of enzymes needed for further development. Nutrient availability is critical here; spores often require simple sugars or amino acids to fuel this process. Caution: In laboratory settings, spores should be provided with a minimal medium containing 2% glucose and essential salts to ensure successful germination.

Step 3: Germ Tube Emergence

The most visible step is the emergence of the germ tube, a small hyphal extension that marks the beginning of vegetative growth. This stage is highly sensitive to environmental cues, such as pH and oxygen levels. For instance, *Candida albicans* spores germinate more efficiently in neutral pH environments, while some soil fungi prefer slightly acidic conditions. Instruction: To observe germ tube formation, inoculate spores onto potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates and incubate at 25°C for 12–24 hours.

Step 4: Hyphal Elongation and Colony Formation

As the germ tube elongates, it develops into a network of hyphae, forming a colony. This stage requires sustained nutrient availability and optimal conditions. Fungi like *Penicillium* can rapidly colonize surfaces, while others, such as *Trichoderma*, are used in biocontrol due to their ability to outcompete pathogens. Takeaway: Understanding this step is key to developing antifungal strategies, as disrupting hyphal growth can prevent fungal spread.

Cautions and Practical Considerations

While fungal spore germination is a natural process, it can have detrimental effects in certain contexts. For example, indoor mold growth poses health risks, and crop pathogens can devastate yields. To mitigate these issues, monitor humidity levels, ensure proper ventilation, and use fungicides judiciously. Comparative analysis shows that chemical fungicides like fluconazole target specific germination stages, while biological controls, such as *Bacillus subtilis*, inhibit spore activation altogether.

In conclusion, fungal spore germination is a multi-step process influenced by environmental and nutritional factors. By dissecting these steps, we gain insights into fungal biology and develop strategies to harness or hinder their growth, depending on the context. Whether in a lab, field, or home, understanding this process empowers us to coexist with fungi more effectively.

Unveiling the Mystery: Where is the G Spot Located?

You may want to see also

Reproductive Capabilities Comparison

Endospores and fungal spores are both survival structures, but their reproductive capabilities differ significantly. Endospores, produced by certain bacteria like *Clostridium* and *Bacillus*, are not reproductive units themselves. Instead, they are dormant, highly resistant forms that allow bacteria to endure extreme conditions such as heat, radiation, and desiccation. When conditions improve, an endospore germinates, reverting to a vegetative bacterial cell capable of reproduction. In contrast, fungal spores are directly involved in reproduction. Produced by fungi through asexual (e.g., conidia) or sexual (e.g., asci, basidiospores) processes, these spores disperse and germinate under favorable conditions to form new fungal individuals. This fundamental distinction highlights their roles: endospores ensure bacterial survival, while fungal spores drive fungal propagation.

To illustrate, consider the lifecycle of *Bacillus anthracis*, the bacterium causing anthrax. When nutrients are scarce, it forms an endospore that can remain viable in soil for decades. Upon encountering a host, the endospore germinates, allowing the bacterium to multiply and cause infection. Fungal spores, such as the conidia of *Aspergillus*, are released in vast quantities into the air. When they land on a suitable substrate, they germinate and grow into hyphae, forming a new fungal colony. This direct reproductive function contrasts with the endospore’s role as a survival mechanism rather than a reproductive agent.

From a practical standpoint, understanding these differences is crucial for control strategies. Endospores require extreme measures for eradication, such as autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes, due to their resistance. Fungal spores, while resilient, are more susceptible to standard disinfection methods like fungicides or UV light. For instance, in healthcare settings, surfaces contaminated with *Clostridioides difficile* spores demand specialized cleaning protocols, whereas mold spores in indoor environments can often be managed with routine cleaning and humidity control.

A comparative analysis reveals that while both structures are resilient, their purposes diverge. Endospores are a bacterial hedge against environmental adversity, ensuring long-term survival without immediate reproductive intent. Fungal spores, however, are explicitly reproductive, enabling fungi to colonize new habitats rapidly. This distinction is vital in fields like microbiology, medicine, and agriculture, where managing these structures dictates outcomes ranging from infection control to crop health.

In summary, endospores and fungal spores exemplify nature’s ingenuity in ensuring survival and propagation, but their reproductive capabilities are not interchangeable. Endospores act as bacterial time capsules, awaiting optimal conditions to resume growth, while fungal spores are the lifeblood of fungal reproduction. Recognizing these differences informs effective strategies for their management, whether in a laboratory, hospital, or field setting.

Exploring Nature's Strategies: How Spores Travel and Disperse Effectively

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$14.08 $14.99

Environmental Survival Mechanisms

Endospores and fungal spores are not directly reproductive entities but rather highly specialized survival structures. They represent a remarkable adaptation to harsh environmental conditions, allowing microorganisms to persist in dormancy until favorable conditions return. This distinction is crucial: while they do not reproduce themselves, they ensure the survival of the species by protecting genetic material during extreme stress.

Consider the environment these spores endure—desiccation, extreme temperatures, UV radiation, and chemical exposure. Endospores, produced by certain bacteria like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, are arguably the most resilient. Their multi-layered structure includes a thick spore coat and a cortex rich in peptidoglycan, providing mechanical strength and chemical resistance. Fungal spores, such as those from *Aspergillus* or *Penicillium*, rely on a chitinous cell wall and melanin pigmentation to withstand environmental assaults. Both structures are metabolically inactive, minimizing energy expenditure while maximizing durability.

To illustrate their survival prowess, endospores can remain viable for centuries. For instance, *Bacillus* endospores have been revived from 25-million-year-old amber, showcasing their longevity. Fungal spores are equally impressive; *Aspergillus* spores can survive temperatures exceeding 60°C, making them resistant to pasteurization. This resilience is not just a biological curiosity—it has practical implications. In healthcare, endospores of *Clostridioides difficile* can persist on surfaces for months, necessitating rigorous disinfection protocols with sporicidal agents like chlorine bleach (5,000–10,000 ppm).

From an ecological perspective, these survival mechanisms ensure microbial persistence across generations. Fungal spores dispersed by wind or water colonize new habitats, maintaining biodiversity in ecosystems. Endospores in soil act as a reservoir, ready to revive and contribute to nutrient cycling when conditions improve. This adaptability underscores their role as environmental sentinels, thriving in niches where other life forms cannot.

In summary, endospores and fungal spores are not reproductive units but environmental survival masters. Their structural ingenuity and metabolic quiescence enable them to withstand extremes, ensuring microbial continuity. Understanding these mechanisms not only deepens our appreciation of microbial life but also informs strategies for disinfection, conservation, and biotechnology. Whether in a hospital, forest, or laboratory, these spores remind us of life’s tenacity in the face of adversity.

Are All Anaerobic Bacteria Spore-Forming? Unraveling the Microbial Mystery

You may want to see also

Genetic Material Transfer Methods

Endospores and fungal spores are not directly reproductive in the sense of producing offspring, but they serve as highly resilient survival structures that can disperse and germinate under favorable conditions. While endospores are formed by certain bacteria to withstand extreme environments, fungal spores are the primary means of reproduction and dispersal in fungi. Both structures, however, play indirect roles in genetic material transfer through their ability to survive, disperse, and interact with their environments. Understanding the mechanisms by which genetic material is transferred in these organisms reveals the complexity of their survival strategies and evolutionary adaptations.

Analytical Perspective:

Genetic material transfer in spore-forming organisms often occurs through horizontal gene transfer (HGT) mechanisms, such as transformation, conjugation, and transduction, rather than traditional reproduction. For instance, bacterial endospores, once germinated, can participate in transformation by taking up free DNA from their environment, incorporating it into their genome. Fungal spores, particularly in basidiomycetes and ascomycetes, can engage in parasexual cycles, where genetic recombination occurs without meiosis through processes like somatic hybridization. These methods allow spores to adapt rapidly to changing environments by acquiring new genetic traits, even though the spores themselves are not directly involved in reproduction.

Instructive Approach:

To facilitate genetic material transfer in spore-forming organisms, researchers often employ laboratory techniques such as protoplast fusion and gene editing tools like CRISPR-Cas9. For fungal spores, protoplast fusion involves removing cell walls, fusing cells, and regenerating hybrid organisms with combined genetic material. In bacteria, endospores can be induced to germinate in controlled conditions, making them susceptible to genetic manipulation. For example, exposing bacterial spores to nutrient-rich media at 37°C for 2–4 hours triggers germination, allowing for subsequent transformation with plasmids carrying foreign DNA. These methods are crucial for biotechnological applications, such as engineering fungi for biofuel production or bacteria for antibiotic resistance studies.

Comparative Analysis:

While both endospores and fungal spores contribute to genetic diversity, the mechanisms differ significantly. Bacterial endospores rely on HGT, which is often mediated by environmental DNA or bacteriophages. In contrast, fungal spores participate in sexual and parasexual cycles, involving the fusion of hyphae or gametes. For example, in *Aspergillus*, spores can undergo heterokaryosis, where genetically distinct nuclei coexist in a single cell, leading to recombination. This contrasts with bacterial endospores, which do not fuse but instead acquire genetic material externally. Despite these differences, both systems highlight the importance of spores as vehicles for genetic innovation and adaptation.

Descriptive Insight:

In natural settings, genetic material transfer involving spores often occurs through environmental interactions. Fungal spores, carried by wind or water, can land in new habitats where they encounter genetically diverse populations, facilitating hybridization. Bacterial endospores, resistant to harsh conditions like UV radiation and desiccation, can persist in soil for decades before germinating and potentially acquiring DNA from neighboring organisms. For instance, in agricultural soils, bacterial spores of *Bacillus* species may take up antibiotic resistance genes from other bacteria, contributing to the spread of resistance. These processes underscore the role of spores as passive yet effective agents of genetic exchange in ecosystems.

Practical Takeaway:

For those studying or manipulating spore-forming organisms, understanding genetic material transfer methods is essential. Researchers can enhance gene transfer efficiency by optimizing conditions such as temperature, pH, and nutrient availability during spore germination. For fungal spores, co-culturing genetically distinct strains on agar plates promotes hybridization, while for bacterial endospores, pre-treating with lysozyme to weaken the spore coat can increase transformation success rates. By leveraging these techniques, scientists can unlock the potential of spores for applications ranging from biotechnology to environmental remediation, ensuring their resilience and adaptability continue to benefit humanity.

Can You Use Bonemeal on Spore Blossoms? A Minecraft Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, both endospores and fungal spores are reproductive structures, but they serve different purposes and are produced by different organisms.

No, endospores are not capable of independent reproduction. They are dormant, resilient structures produced by certain bacteria to survive harsh conditions, while fungal spores are directly involved in fungal reproduction.

Yes, when endospores and fungal spores germinate, they can both develop into new organisms. Endospores grow into bacterial cells, while fungal spores grow into new fungal structures like hyphae or yeast cells.

No, endospores are produced by certain bacteria (e.g., *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*), while fungal spores are produced by fungi, such as molds, yeasts, and mushrooms. They belong to entirely different biological kingdoms.