Flat mushrooms, often found in various environments, can be a source of confusion for foragers and nature enthusiasts due to their diverse appearances and potential toxicity. While some flat mushrooms, like the common oyster mushroom, are edible and prized in culinary traditions, others, such as certain species of Amanita, can be highly poisonous and even life-threatening if consumed. Identifying flat mushrooms accurately is crucial, as their morphology alone is not always a reliable indicator of safety. Factors such as habitat, spore color, and the presence of specific characteristics like a ring or bulbous base can help distinguish between edible and toxic varieties. Therefore, it is essential to consult expert guides or mycologists before consuming any wild mushrooms to avoid accidental poisoning.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Toxicity | Some flat mushrooms are toxic, while others are edible. Common toxic species include the Amanita ocreata (Death Angel) and Galerina marginata (Deadly Galerina). |

| Edible Species | Edible flat mushrooms include Agaricus bisporus (Button Mushroom), Pleurotus ostreatus (Oyster Mushroom), and Lentinula edodes (Shiitake). |

| Physical Traits | Flat mushrooms often have a cap with a flat or slightly convex shape. Toxic species may have white gills, a ring on the stem, or a bulbous base. |

| Habitat | Found in various environments, including forests, grasslands, and gardens. Toxic species often grow near trees or in decaying wood. |

| Symptoms of Poisoning | Symptoms from toxic flat mushrooms can include gastrointestinal distress, hallucinations, organ failure, and in severe cases, death. |

| Identification | Accurate identification requires expertise. Relying on color, shape, or habitat alone is insufficient; consult a mycologist or field guide. |

| Prevention | Avoid consuming wild mushrooms unless positively identified by an expert. Cooking does not always neutralize toxins. |

| Seasonality | Many flat mushrooms, both edible and toxic, are more common in late summer to fall, depending on the species and region. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Identifying poisonous flat mushrooms: key features to look for in toxic species

- Common flat mushroom varieties: which are safe and which are dangerous to consume

- Symptoms of flat mushroom poisoning: recognizing signs of toxicity after ingestion

- Safe foraging practices: how to avoid poisonous flat mushrooms in the wild

- Edible flat mushroom look-alikes: distinguishing between toxic and non-toxic species accurately

Identifying poisonous flat mushrooms: key features to look for in toxic species

Flat mushrooms, often found in forests and gardens, can be deceivingly innocuous. While many are edible, several toxic species share a similar flattened cap structure, making identification crucial. One key feature to look for is the presence of white gills that bruise brown—a hallmark of the deadly Amanita genus, including the notorious Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*). This subtle discoloration, often occurring within minutes of handling, signals the presence of amatoxins, which can cause severe liver damage even in small doses (as little as 30 grams can be fatal for an adult). Always inspect the gill color and response to pressure before considering any flat mushroom safe.

Another critical characteristic is the partial veil remnants, often seen as a skirt-like ring on the stem or volva at the base. Poisonous species like the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*) retain these structures, which are rarely found in edible varieties. The volva, in particular, is a red flag—it resembles a cup-like structure at the mushroom’s base and is a telltale sign of toxicity. If you encounter a flat mushroom with these features, avoid handling it without gloves, as even skin contact can transfer toxins.

Texture and odor also play a role in identification. Toxic flat mushrooms often have a slimy or sticky cap, especially in humid conditions, whereas edible varieties like the Oyster mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) typically have a dry, velvety surface. Additionally, a sharp, unpleasant odor—described as chemical or bleach-like—is common in poisonous species. For instance, the Ivory Funnel (*Clitocybe dealbata*) emits a distinct fruity smell but contains muscarine, a toxin causing sweating, salivation, and blurred vision within 15–30 minutes of ingestion. Trust your senses; if a mushroom smells off, it’s best left untouched.

Lastly, consider the habitat and seasonality. Poisonous flat mushrooms often thrive in specific environments, such as under oak or birch trees, where they form mycorrhizal relationships. The Death Cap, for example, is frequently found near oak trees in late summer to fall. Edible species like the Chanterelle (*Cantharellus cibarius*) prefer similar habitats but have distinct forked gills and a fruity aroma. Always cross-reference location and season with known toxic species in your region, and when in doubt, consult a field guide or mycologist. Remember, no single feature guarantees safety—a combination of observations is essential for accurate identification.

Are Brown Cone Head Mushrooms Poisonous? A Safety Guide

You may want to see also

Common flat mushroom varieties: which are safe and which are dangerous to consume

Flat mushrooms, often found in forests and fields, come in a variety of shapes and sizes, but their thin, delicate caps can make identification challenging. Among these, the Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) stands out as a safe and popular choice for foragers and chefs alike. Its distinctive fan-like shape and creamy texture make it a favorite in culinary dishes worldwide. Rich in protein, vitamins, and minerals, this mushroom is not only safe but also highly nutritious. However, it’s crucial to ensure proper cooking, as consuming raw oyster mushrooms can cause digestive discomfort due to their tough cell walls.

In contrast, the Deadly Galerina (Galerina marginata) is a flat mushroom that poses a severe threat. Often mistaken for edible species like the honey mushroom, it contains amatoxins, which can cause liver and kidney failure if ingested. Symptoms may not appear for 6–24 hours, making it particularly dangerous. Foragers should avoid any small, brown, flat mushrooms growing on wood unless they are absolutely certain of the identification. Even experienced mushroom hunters have fallen victim to this deadly look-alike, underscoring the importance of caution.

Another safe option is the Shaggy Mane (Coprinus comatus), recognizable by its elongated, cylindrical cap that flattens with age. This mushroom is not only edible but also a delicacy when young, with a flavor reminiscent of seafood. However, it has a unique characteristic: it autodigests within hours of being picked, turning into a black, inky mess. Foragers should consume or cook it immediately after harvesting. While it’s safe for most people, those sensitive to alcohol should avoid it, as it can cause a reaction similar to drinking wine due to its natural fermentation process.

For a comparative perspective, the Flat-Capped Milkling (Lactarius obsoletus) is a flat mushroom that exudes a milky latex when cut. While not deadly, it is considered inedible due to its extremely bitter taste and potential to cause gastrointestinal distress. Its resemblance to other milk-cap mushrooms can be misleading, but its strong, unpleasant flavor usually deters accidental consumption. Foragers should focus on identifying key features like spore color and habitat to avoid confusion with similar species.

In conclusion, while some flat mushrooms like the oyster and shaggy mane are safe and delicious, others like the deadly galerina can be lethal. Proper identification is paramount, and when in doubt, it’s best to consult an expert or avoid consumption altogether. Practical tips include carrying a field guide, using a spore print test, and never eating a mushroom based solely on its appearance. Remember, the line between a gourmet meal and a trip to the hospital can be as thin as a mushroom’s cap.

Are Chanterelle Mushrooms Safe for Dogs? A Toxicity Guide

You may want to see also

Symptoms of flat mushroom poisoning: recognizing signs of toxicity after ingestion

Flat mushrooms, often found in various environments, can be deceivingly innocuous. While some species are edible and even prized in culinary traditions, others harbor toxins that can lead to severe health consequences. Recognizing the symptoms of flat mushroom poisoning is crucial for timely intervention, as delays can exacerbate toxicity and complicate treatment. The onset of symptoms typically occurs within 6 to 24 hours after ingestion, depending on the species and the amount consumed. Early signs may be subtle, such as mild gastrointestinal discomfort, but they can rapidly escalate to life-threatening conditions if left unaddressed.

Analyzing the symptoms, gastrointestinal distress is often the first indicator of flat mushroom poisoning. This includes nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain, which can be mistaken for food poisoning or a viral infection. However, unlike common stomach bugs, these symptoms are persistent and may worsen over time. For instance, the *Amanita phalloides* (Death Cap) and *Galerina marginata* (Deadly Galerina) are flat mushrooms notorious for causing severe liver and kidney damage. In such cases, initial gastrointestinal symptoms are followed by a latent phase where the individual may feel temporarily better, only to experience jaundice, seizures, or organ failure within 24 to 48 hours.

Instructively, it’s essential to monitor for neurological symptoms, which can manifest as confusion, dizziness, or hallucinations. These signs suggest that the toxin has affected the central nervous system, a hallmark of poisoning by certain flat mushrooms like the *Conocybe filaris* (Cone-bearing Conocybe). Children and the elderly are particularly vulnerable due to their lower body mass and potentially weaker immune systems. If a child exhibits sudden behavioral changes or loses consciousness after being in an area with flat mushrooms, immediate medical attention is imperative. Dosage matters here—even a small bite of a toxic species can be fatal for a child.

Comparatively, flat mushroom poisoning differs from other types of mushroom toxicity in its latency and severity. For example, while *Psathyrella candolleana* (Candolle’s Psathyrella) may cause mild gastrointestinal upset, it is far less dangerous than the *Lepiota brunneoincarnata* (Fatal Lepiota), which can lead to acute liver failure. Practical tips include avoiding consumption of wild mushrooms unless positively identified by an expert, and always cooking mushrooms thoroughly, though this does not neutralize all toxins. Carrying a portable mushroom identification guide or using a reliable app can also reduce risk.

Descriptively, the progression of symptoms can be likened to a storm gathering on the horizon. What begins as a few rumblings of discomfort can quickly escalate into a full-blown crisis. For instance, a family in Oregon experienced this firsthand after mistaking *Amanita ocreata* (Destroying Angel) for edible mushrooms. Within hours, they developed severe vomiting and diarrhea, followed by extreme lethargy and dark urine—signs of liver damage. Their swift admission to the hospital, where they received activated charcoal and supportive care, likely saved their lives. This underscores the importance of recognizing symptoms early and seeking medical help without delay.

Are Washington State's Bolete Mushrooms Safe to Eat?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Safe foraging practices: how to avoid poisonous flat mushrooms in the wild

Flat mushrooms, often found in forests and fields, can be both a forager’s delight and a hidden danger. While some species, like the edible *Agaricus bisporus* (button mushroom), are safe and nutritious, others, such as the deadly *Amanita phalloides* (death cap), can cause severe poisoning or even fatalities. The key to safe foraging lies in precise identification and cautious practices. Always carry a reliable field guide or use a trusted mushroom identification app, but remember: technology is no substitute for hands-on knowledge. If in doubt, leave it out—no meal is worth risking your health.

One critical step in avoiding poisonous flat mushrooms is understanding their distinguishing features. Poisonous species often have subtle but consistent markers: white gills, a bulbous base, or a ring on the stem. For instance, the death cap resembles the edible paddy straw mushroom but has a cup-like volva at its base. Another red flag is coloration; while not all brightly colored mushrooms are toxic, many poisonous flat mushrooms have unassuming hues, blending into their surroundings. Always examine the mushroom’s underside for gill structure and spore color, as these traits are less variable than cap appearance.

Foraging should never be a solo activity, especially for beginners. Join a local mycological society or attend guided foraging walks to learn from experienced foragers. They can teach you the "rule of six" for safe identification: note the mushroom’s cap shape, color, size, gill attachment, stem features, and habitat. Practice makes perfect—start by identifying common edible species before attempting to distinguish toxic look-alikes. Children under 12 should never handle wild mushrooms, as their developing immune systems are more susceptible to toxins.

Finally, adopt a "forage-to-cook" mindset. Never consume a wild mushroom raw, as some toxins are neutralized by heat. Even edible species can cause digestive upset if not properly prepared. If you suspect poisoning, seek medical attention immediately. Symptoms like nausea, vomiting, or abdominal pain can appear within 6–24 hours, depending on the toxin. Keep a sample of the consumed mushroom for identification, as this can aid treatment. Safe foraging is a blend of knowledge, caution, and respect for nature’s complexities—master these, and the wild’s bounty can be yours to enjoy.

Are Shrooms Poisonous? Uncovering the Truth About Magic Mushrooms

You may want to see also

Edible flat mushroom look-alikes: distinguishing between toxic and non-toxic species accurately

Flat mushrooms, often found in forests and fields, can be deceivingly similar in appearance, making it crucial to distinguish between edible and toxic species. One of the most notorious examples is the Amanita muscaria, a toxic mushroom with a flat cap, often mistaken for the edible Agaricus bisporus due to its similar shape and color. The key difference lies in the gills and stem base: the Amanita has white gills and a bulbous base with a ring, while the Agaricus has pinkish-brown gills and a smooth, even stem. Misidentification can lead to severe gastrointestinal symptoms or, in extreme cases, organ failure. Always examine the mushroom’s underside and stem closely before consumption.

To accurately identify edible flat mushrooms, follow a systematic approach. First, document the mushroom’s habitat—edible species like the Oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) grow on wood, while toxic look-alikes like the Jack-O’-Lantern (Omphalotus olearius) also favor woody substrates but emit a bioluminescent glow in the dark. Second, test for spore color by placing the cap gill-side down on a white sheet of paper overnight. Edible species typically produce white or brown spores, while toxic ones may produce green or black spores. Lastly, smell and touch the mushroom—edible varieties often have a pleasant, earthy aroma, whereas toxic species may smell pungent or chemical.

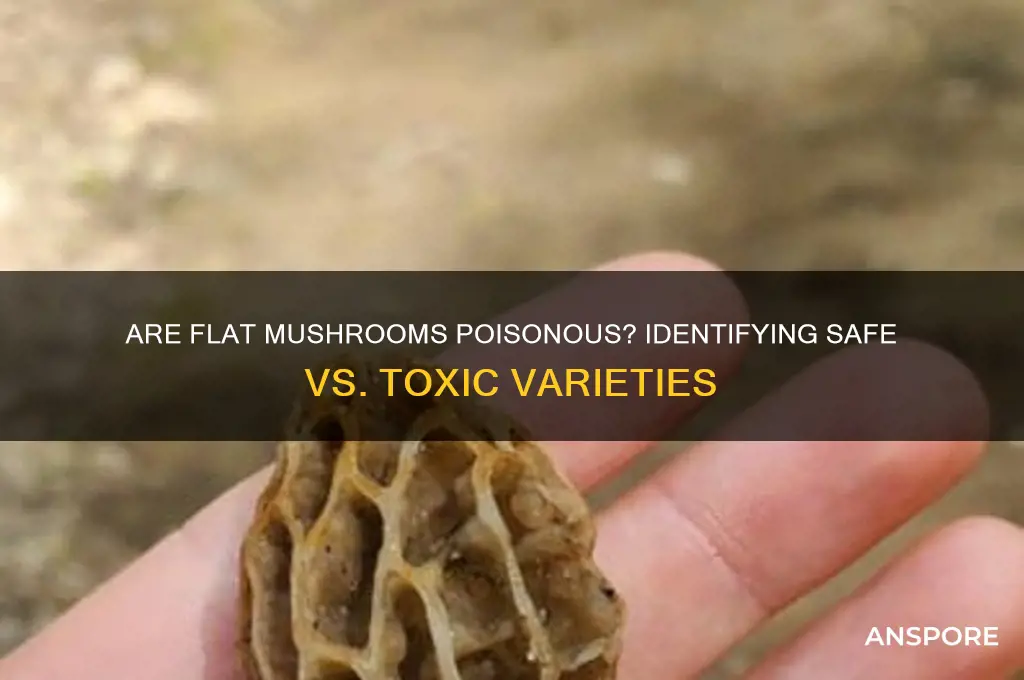

A persuasive argument for caution arises when considering the False Morel (Gyromitra esculenta), a toxic look-alike of the edible True Morel (Morchella spp.). Both have a honeycomb-like cap, but the False Morel’s cap is brain-like and brittle, while the True Morel’s is more spongy and elastic. Ingesting False Morels can cause severe poisoning, even after cooking, due to the toxin gyromitrin. To avoid risk, always consult a field guide or mycologist, especially if foraging for the first time. Remember, no meal is worth risking your health.

Comparing the Chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius) and its toxic doppelgänger, the Jack-O’-Lantern, highlights the importance of detail. Chanterelles have forked gills that run down the stem, a fruity aroma, and a golden-yellow color, while Jack-O’-Lanterns have true gills and a brighter orange hue. A practical tip: tear a piece of the mushroom—Chanterelles will have a fibrous texture, whereas Jack-O’-Lanterns will be more brittle. This simple test can save lives, as Jack-O’-Lanterns contain toxins that cause severe cramps and dehydration.

In conclusion, distinguishing between edible flat mushrooms and their toxic look-alikes requires careful observation, knowledge of key characteristics, and a willingness to err on the side of caution. Always cross-reference multiple features—habitat, spore color, texture, and smell—before making a decision. For beginners, start with easily identifiable species like Oyster mushrooms and avoid those with dangerous doppelgängers like Amanitas or False Morels. When in doubt, throw it out—the forest will always offer another opportunity, but your health is irreplaceable.

Are White Mushrooms Poisonous to Dogs? Essential Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all flat mushrooms are poisonous. Some flat mushrooms, like the Oyster mushroom, are edible and safe to consume.

Identifying poisonous flat mushrooms requires knowledge of specific characteristics, such as color, gills, and spore print. Consulting a field guide or expert is recommended.

No, flat mushrooms with white gills are not always poisonous. However, some toxic species, like the Destroying Angel, have white gills, so caution is advised.

No, cooking does not remove toxins from poisonous flat mushrooms. It’s crucial to avoid consuming any mushroom unless you are certain it is safe.