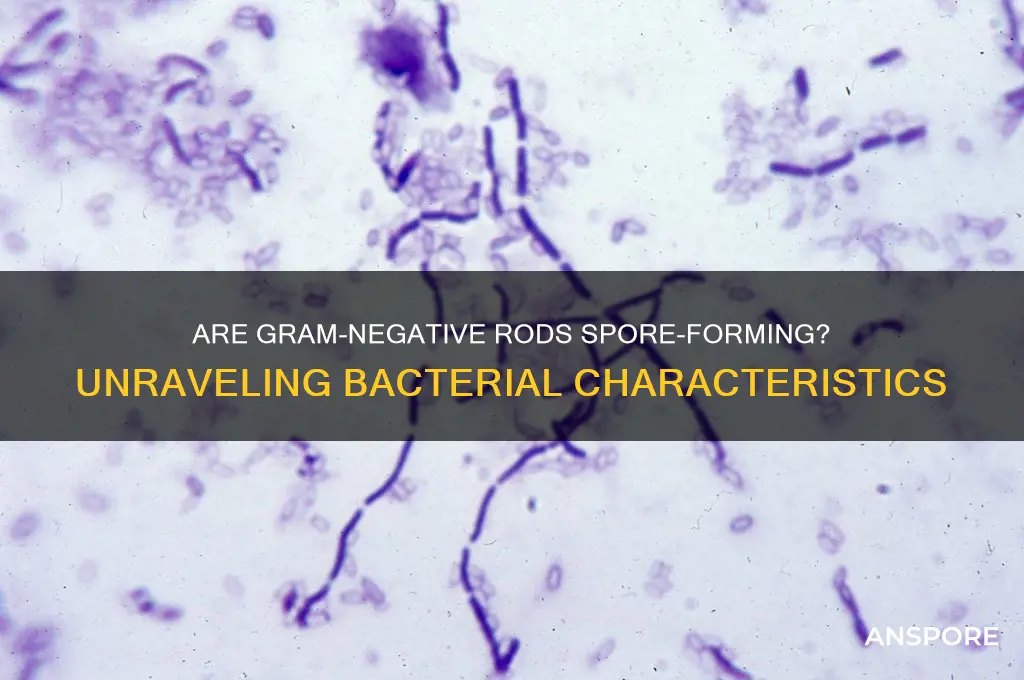

The question of whether Gram-negative rods are spore-forming is a critical one in microbiology, as it directly impacts our understanding of bacterial survival, pathogenicity, and treatment strategies. Gram-negative rods, characterized by their thin peptidoglycan layer and outer membrane, are a diverse group of bacteria that include both commensal and pathogenic species. While spore formation is a well-known survival mechanism in certain Gram-positive bacteria, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, it is generally rare among Gram-negative rods. However, there are exceptions, such as *Xenorhabdus* and *Photorhabdus*, which are known to produce spores under specific conditions. Understanding the spore-forming capabilities of Gram-negative rods is essential for fields like medicine, environmental science, and biotechnology, as it influences their resistance to antibiotics, environmental persistence, and potential applications in industrial processes.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Identification Methods: Techniques to detect spore-forming Gram-negative rods in clinical and environmental samples

- Pathogenic Species: Known Gram-negative rod pathogens capable of forming spores and causing infections

- Sporulation Process: Mechanisms and conditions required for Gram-negative rods to form spores

- Clinical Significance: Impact of spore-forming Gram-negative rods on human and animal health

- Antimicrobial Resistance: Challenges in treating infections caused by spore-forming Gram-negative rods

Identification Methods: Techniques to detect spore-forming Gram-negative rods in clinical and environmental samples

Spore-forming Gram-negative rods are rare but clinically significant, with *Stenotrophomonas maltophilia* and *Chryseobacterium* spp. being notable examples. Identifying these organisms in clinical and environmental samples requires a combination of traditional microbiological techniques and advanced molecular methods. Here’s a structured approach to their detection and confirmation.

Cultivation and Staining: The Foundation of Identification

Begin with selective media to isolate Gram-negative rods, such as MacConkey agar, which inhibits Gram-positive bacteria. For spore detection, heat-shock samples at 80°C for 10–15 minutes to activate spore germination. Subculture onto nutrient agar and observe for colony morphology—*S. maltophilia*, for instance, forms mucoid colonies. Perform Gram staining to confirm rod morphology and negative staining. While this step is preliminary, it narrows the search and guides further testing.

Spore Confirmation: Microscopy and Biochemical Tests

To confirm spore formation, employ the Schaeffer-Fulton stain, which differentiates spores (green) from vegetative cells (red). This method is critical for distinguishing spore-formers from non-spore-forming rods. Supplement this with biochemical tests: *S. maltophilia* is oxidase-negative and produces a yellow pigment, while *Chryseobacterium* is oxidase-positive. Automated systems like VITEK 2 can streamline identification but may require manual confirmation for uncommon species.

Molecular Techniques: Precision in Detection

For definitive identification, use polymerase chain reaction (PCR) targeting 16S rRNA genes or species-specific markers. Real-time PCR assays can detect *S. maltophilia* with primers targeting the *smeD* gene, offering sensitivity and specificity. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) provides the highest resolution, allowing for strain typing and antimicrobial resistance profiling. These methods are particularly useful in complex samples or when traditional methods yield ambiguous results.

Environmental Sampling: Practical Considerations

In environmental settings, focus on water and soil samples, as spore-forming Gram-negative rods can persist in these matrices. Filter large volumes (e.g., 100 mL) of water through 0.45 μm membranes, then incubate on R2A agar, which supports the growth of stressed or slow-growing bacteria. For soil, use a 1:10 dilution in sterile saline and serially dilute before plating. Regular monitoring is essential in healthcare settings to prevent nosocomial infections, especially in water systems and medical devices.

Challenges and Takeaways

Misidentification is common due to the rarity of spore-forming Gram-negative rods and their overlapping biochemical profiles. Always correlate phenotypic and genotypic results for accuracy. While *S. maltophilia* is inherently resistant to multiple antibiotics, early detection can guide appropriate therapy, such as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) at 15–20 mg/kg/day for adults. In environmental contexts, eradication may require disinfection with chlorine-based agents or UV treatment. Mastery of these techniques ensures timely and accurate identification, critical for both clinical management and public health.

Are Black Mold Spores Black? Unveiling the Truth Behind the Color

You may want to see also

Pathogenic Species: Known Gram-negative rod pathogens capable of forming spores and causing infections

Gram-negative rod bacteria are typically known for their outer membrane structure and resistance to antibiotics, but their ability to form spores is less common. However, certain pathogenic species within this group do possess the unique capability of sporulation, enabling them to survive harsh conditions and cause infections under specific circumstances. One such example is *Bacillus cereus*, often misclassified due to its gram-variable nature but primarily considered gram-positive. Yet, its pathogenicity and spore-forming ability make it a critical reference point for understanding similar gram-negative threats.

Among true gram-negative spore-formers, *Clostridioides difficile* stands out, though it is gram-positive. However, *Stenotrophomonas maltophilia* and *Chryseobacterium* spp. are gram-negative rods that, while not classically spore-forming, exhibit resilience akin to spore-formers. These species are increasingly recognized as opportunistic pathogens, particularly in immunocompromised individuals or healthcare settings. For instance, *S. maltophilia* is often isolated from respiratory tract infections in cystic fibrosis patients, with treatment requiring high-dose trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (15–20 mg/kg/day of trimethoprim component) due to its multidrug resistance.

A lesser-known but clinically significant pathogen is *Brevundimonas diminuta*, a gram-negative rod occasionally associated with bloodstream infections in hospitalized patients. While not spore-forming, its environmental persistence mirrors spore-formers, highlighting the need for rigorous infection control measures. Similarly, *Achromobacter xylosoxidans* is an emerging pathogen in cystic fibrosis patients, often requiring combination therapy with ceftazidime (100–150 mg/kg/day) and ticarcillin-clavulanate due to its intrinsic resistance profile.

Understanding these pathogens requires a comparative approach. Unlike gram-positive spore-formers like *Clostridium botulinum*, gram-negative rods lack the classical sporulation machinery but compensate with mechanisms like biofilm formation and intrinsic antibiotic resistance. For instance, *Burkholderia cepacia* complex (Bcc) species, though not spore-forming, are notorious for their environmental persistence and ability to cause severe infections in cystic fibrosis patients. Treatment often involves ceftazidime (2 g every 8 hours) combined with aminoglycosides, but outcomes remain challenging due to their multidrug resistance.

In practical terms, healthcare providers must remain vigilant for these pathogens, particularly in high-risk populations. Diagnostic labs should employ extended culture techniques to detect slow-growing or environmentally resilient species. Infection prevention strategies, such as hand hygiene and surface disinfection with sporicidal agents like hydrogen peroxide or bleach, are critical to controlling outbreaks. For patients, education on recognizing early infection symptoms—fever, respiratory distress, or wound discharge—can lead to timely intervention, reducing morbidity and mortality associated with these unique gram-negative pathogens.

Understanding Spores: Definition, Function, and Significance in Nature

You may want to see also

Sporulation Process: Mechanisms and conditions required for Gram-negative rods to form spores

Gram-negative rods are traditionally classified as non-spore forming bacteria, a characteristic that distinguishes them from their Gram-positive counterparts like *Clostridium* and *Bacillus*. However, recent research has challenged this dogma, revealing that certain Gram-negative species, such as *Xanthomonas campestris* and *Achromobacter* spp., exhibit sporulation-like mechanisms under specific environmental stresses. These findings underscore the need to explore the sporulation process in Gram-negative rods, focusing on the mechanisms and conditions that enable this rare phenomenon.

The sporulation process in Gram-negative rods is not as well-defined as in Gram-positive bacteria, but it involves similar stress-induced responses. Key mechanisms include the activation of sigma factors, which regulate gene expression in response to environmental cues such as nutrient depletion, desiccation, or extreme temperatures. For instance, *Xanthomonas campestris* initiates a sporulation-like process through the upregulation of genes involved in exopolysaccharide production and cell wall restructuring, forming a protective cyst-like structure. This process, while not true sporulation, shares functional similarities with spore formation in terms of survival and resilience.

To induce sporulation-like mechanisms in Gram-negative rods, specific conditions must be met. These include prolonged exposure to suboptimal growth environments, such as nutrient-limited media or high salinity. For example, *Achromobacter* spp. have been observed to form cyst-like structures when cultured in media with reduced carbon sources and elevated NaCl concentrations (up to 5%). Additionally, temperature shifts, particularly from optimal growth temperatures (e.g., 37°C) to lower temperatures (e.g., 4°C), can trigger stress responses that mimic sporulation. Practical tips for researchers include maintaining consistent stress conditions for at least 72 hours and monitoring cellular morphology using phase-contrast microscopy to detect structural changes.

Comparatively, the sporulation process in Gram-negative rods differs significantly from that of Gram-positive bacteria. While Gram-positive spores are characterized by a thick protein coat and cortex layer, Gram-negative "spores" lack these structures, relying instead on modified cell walls and extracellular matrices for protection. This distinction highlights the evolutionary divergence in survival strategies between the two groups. However, understanding these mechanisms in Gram-negative rods could provide insights into their persistence in harsh environments, such as soil or water treatment systems, and inform strategies for their control in industrial or clinical settings.

In conclusion, while true sporulation remains rare in Gram-negative rods, emerging evidence suggests that these bacteria employ sporulation-like mechanisms to survive adverse conditions. By studying the specific triggers and molecular pathways involved, researchers can gain a deeper understanding of bacterial resilience and potentially develop targeted interventions to combat Gram-negative pathogens in various contexts. This knowledge bridges the gap between traditional classifications and the dynamic capabilities of bacterial survival strategies.

Understanding Mold Spores Lifespan: How Long Do They Survive?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Clinical Significance: Impact of spore-forming Gram-negative rods on human and animal health

Spore-forming Gram-negative rods are a rare but clinically significant subset of bacteria, blending the resilience of spore formation with the inherent challenges of treating Gram-negative infections. Unlike their more common counterparts, these organisms can survive extreme conditions, including heat, desiccation, and disinfectants, by forming spores. This dual threat—sporulation and Gram-negative characteristics—amplifies their potential to cause severe, hard-to-treat infections in both humans and animals. Understanding their impact is critical for targeted prevention, diagnosis, and treatment strategies.

One of the most notorious examples is *Bacillus cereus*, a Gram-variable rod that occasionally exhibits Gram-negative staining and forms spores. While primarily associated with foodborne illness, its spores can contaminate medical devices, leading to nosocomial infections. In animals, *B. cereus* can cause necrotic enteritis in poultry, resulting in significant economic losses. Treatment is complicated by spore resistance to antibiotics and the bacterium’s ability to produce toxins. For instance, in humans, doses of contaminated food as small as 10^5–10^6 CFU/g can trigger symptoms like diarrhea and vomiting within 6–15 hours. In veterinary settings, prophylactic measures such as feed supplementation with probiotics or organic acids are often employed to mitigate outbreaks.

Another example is *Stenotrophomonas maltophilia*, a non-spore-forming Gram-negative rod that highlights the broader challenges of treating such bacteria. While it does not form spores, its intrinsic resistance to multiple antibiotics mirrors the clinical complexity of spore-forming counterparts. In immunocompromised patients, *S. maltophilia* can cause pneumonia, bacteremia, and meningitis, with mortality rates exceeding 30%. Similarly, in animals, it has been isolated from respiratory infections in cattle and poultry, though its impact is less studied. Treatment often relies on combination therapy, such as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) at 8–10 mg/kg every 12 hours for humans, adjusted for renal function. In animals, dosage varies by species and weight, emphasizing the need for precise veterinary guidance.

The clinical significance of spore-forming Gram-negative rods extends beyond direct infection to their role in environmental persistence. Spores can contaminate water, soil, and healthcare facilities, serving as reservoirs for transmission. For instance, *Bacteroides fragilis*, while not spore-forming, exemplifies the challenges of anaerobic Gram-negative rods in clinical settings. Its ability to cause abscesses and resist beta-lactam antibiotics parallels the treatment hurdles posed by spore-formers. In animals, such infections often require surgical drainage and prolonged antibiotic therapy, such as metronidazole at 15 mg/kg every 8 hours for dogs. Practical tips for prevention include rigorous sterilization of medical equipment and use of spore-specific disinfectants like hydrogen peroxide vapor.

In conclusion, the impact of spore-forming Gram-negative rods on human and animal health is profound, driven by their dual resilience and pathogenicity. Clinicians and veterinarians must remain vigilant, employing targeted diagnostics, such as spore staining and molecular assays, to identify these organisms. Treatment strategies should combine antimicrobial therapy with environmental decontamination to break the cycle of transmission. For high-risk populations, such as immunocompromised patients or livestock in crowded conditions, proactive measures like vaccination (where available) and biosecurity protocols are essential. By addressing both the clinical and ecological dimensions, we can mitigate the unique threats posed by these bacteria.

Are Cubensis Spores Legal? Exploring the Legal Landscape

You may want to see also

Antimicrobial Resistance: Challenges in treating infections caused by spore-forming Gram-negative rods

Gram-negative rods are typically non-spore-forming bacteria, but exceptions like *Stenotrophomonas maltophilia* and *Chryseobacterium* species blur this line, complicating treatment strategies. These organisms, though rare, pose significant challenges due to their intrinsic resistance mechanisms and ability to form biofilms, which exacerbate antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Unlike their more common counterparts, spore-forming Gram-negative rods can survive harsh conditions, including exposure to antibiotics, making eradication difficult. This unique characteristic demands tailored therapeutic approaches, particularly in immunocompromised patients where infections are more severe and recurrent.

Treating infections caused by these bacteria requires a multi-pronged strategy. First, accurate identification is critical. Conventional methods may misidentify these organisms, so advanced techniques like matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) are essential for precise diagnosis. Once identified, empiric therapy often involves broad-spectrum antibiotics such as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), which is typically dosed at 160 mg/800 mg every 12 hours for adults. However, resistance to TMP-SMX is increasingly reported, necessitating combination therapy with agents like ticarcillin-clavulanate or minocycline. Dosage adjustments are crucial for pediatric populations, with TMP-SMX dosed at 5 mg/kg/day of trimethoprim component, divided every 12 hours.

The challenges extend beyond treatment selection. These bacteria often colonize medical devices, forming biofilms that shield them from antibiotics. For instance, *S. maltophilia* is a notorious contaminant in respiratory equipment, leading to ventilator-associated pneumonia. Decontamination protocols must be rigorous, involving 70% ethanol or hydrogen peroxide-based disinfectants. Additionally, prolonged antibiotic use in these cases increases the risk of selecting for resistant strains, underscoring the need for antimicrobial stewardship programs to monitor and optimize therapy.

A comparative analysis reveals that spore-forming Gram-negative rods share some resistance mechanisms with Gram-positive spore-formers like *Clostridioides difficile*, such as efflux pumps and β-lactamase production. However, their Gram-negative outer membrane provides an additional barrier to antibiotics, making them inherently more resistant. This duality complicates treatment, as strategies effective against Gram-positive spores, like spore germinants, are ineffective here. Instead, novel approaches such as phage therapy or antimicrobial peptides hold promise but remain experimental.

In conclusion, addressing AMR in spore-forming Gram-negative rods requires a combination of precise diagnostics, targeted therapy, and infection control measures. Clinicians must remain vigilant, adapting strategies to combat these resilient pathogens. Practical tips include avoiding unnecessary antibiotic use, optimizing dosing based on patient factors, and collaborating with microbiologists to track resistance patterns. As these infections become more prevalent, a proactive, evidence-based approach is essential to mitigate their impact.

Effective Ways to Eliminate Mold Spores in Your Home Safely

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Most gram-negative rods are not spore-forming. However, there are rare exceptions, such as *Adenosina vagae* and *Oceanobacillus iheyensis*, which are gram-variable or atypical cases.

There are no well-known or typical examples of spore-forming gram-negative rods. Spore formation is primarily associated with gram-positive bacteria like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*.

Under normal conditions, gram-negative rods do not produce spores. Sporulation is a characteristic feature of certain gram-positive bacteria, not gram-negative bacteria.

Gram-negative rods lack the genetic and structural mechanisms required for sporulation, which are present in some gram-positive bacteria. Their cell wall structure and metabolic pathways differ significantly.

No, true gram-negative bacteria do not form spores. Sporulation is exclusive to certain gram-positive bacteria, and any reported cases of gram-negative spore-formers are rare, atypical, or misclassified.