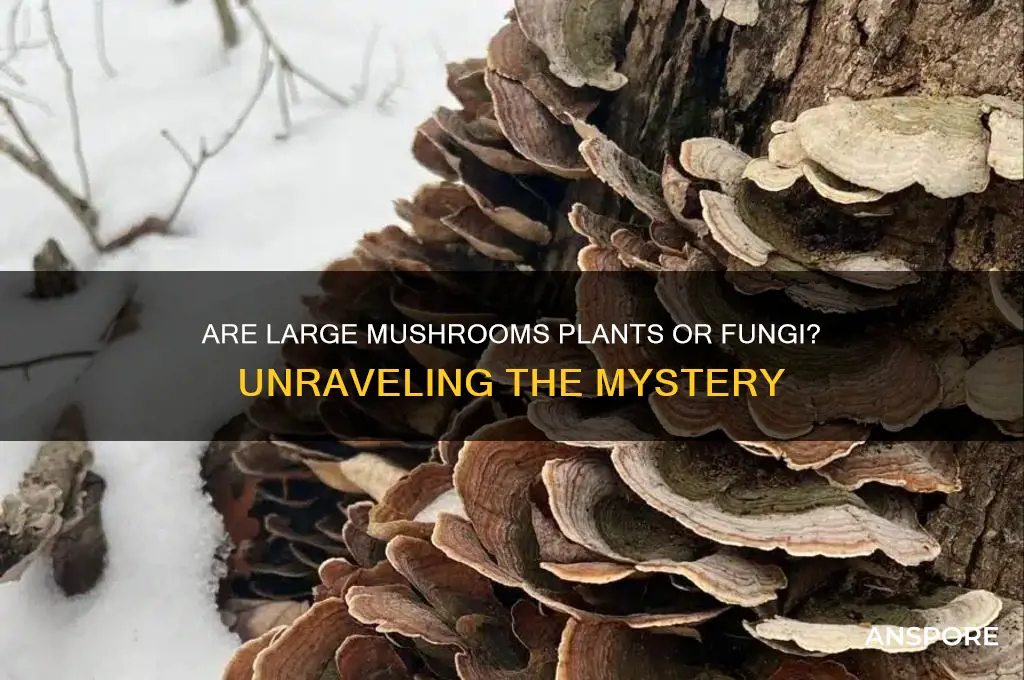

Mushrooms, often mistaken for plants due to their stationary nature and visible fruiting bodies, are actually a type of fungus. Unlike plants, which produce their own food through photosynthesis, fungi like mushrooms obtain nutrients by decomposing organic matter. This fundamental difference in biology places mushrooms in the kingdom Fungi, separate from the plant kingdom. Their unique structure, which includes mycelium—a network of thread-like cells—further distinguishes them from plants. Understanding whether large mushrooms are plants or fungi not only clarifies their classification but also highlights their vital role in ecosystems as decomposers and nutrient recyclers.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Kingdom | Fungi (not Plantae) |

| Cell Walls | Chitin (not cellulose like plants) |

| Nutrition | Heterotrophic (absorb nutrients from organic matter) |

| Chlorophyll | Absent (cannot perform photosynthesis) |

| Reproduction | Spores (not seeds or pollen) |

| Growth Medium | Decomposing organic material (not soil directly) |

| Vascular Tissue | Absent (no xylem or phloem) |

| Size | Varies; large mushrooms are fruiting bodies of fungi |

| Ecological Role | Decomposers (break down organic matter) |

| Taxonomy | Separate kingdom (Fungi) distinct from plants |

Explore related products

$14.99

What You'll Learn

Mushroom Classification Basics

Mushrooms have long been a subject of curiosity, often mistaken for plants due to their stationary nature and visible fruiting bodies. However, a fundamental understanding of mushroom classification reveals that they are not plants but fungi. Fungi constitute their own kingdom in the biological classification system, distinct from plants, animals, and bacteria. This distinction is rooted in several key differences: fungi lack chlorophyll and cannot perform photosynthesis, relying instead on absorbing nutrients from their environment. Additionally, their cell walls are composed of chitin, unlike the cellulose found in plant cell walls. These characteristics place mushrooms squarely in the fungal kingdom, making them more closely related to yeast and mold than to plants.

The classification of mushrooms begins with their placement in the phylum Basidiomycota or Ascomycota, the two primary groups within the fungal kingdom that include most mushroom-producing species. Basidiomycota, often referred to as "club fungi," produce spores on structures called basidia, while Ascomycota, or "sac fungi," produce spores in sac-like structures called asci. Most of the large, familiar mushrooms, such as button mushrooms, shiitakes, and portobellos, belong to the Basidiomycota phylum. Understanding these phyla is essential for grasping the broader taxonomy of mushrooms, as they represent the first major branching points in fungal classification.

Within these phyla, mushrooms are further classified into orders, families, genera, and species based on morphological, ecological, and genetic traits. For example, the order Agaricales includes many common gilled mushrooms, while the family Amanitaceae contains the well-known Amanita genus, which includes both edible and highly toxic species. Key features used in classification include the structure of the fruiting body (e.g., gills, pores, or spines), spore color, and microscopic characteristics like spore shape and size. These details are critical for accurate identification, as mushrooms can vary widely in appearance despite sharing a common fungal lineage.

One of the most important aspects of mushroom classification is distinguishing between edible and poisonous species, as misidentification can have severe consequences. While some mushrooms, like the Amanita muscaria (fly agaric), are easily recognizable by their bright red caps and white spots, others may closely resemble edible varieties. For instance, the deadly Amanita phalloides (death cap) bears a striking resemblance to edible straw mushrooms. This highlights the need for rigorous classification methods, often involving field guides, spore prints, and even DNA analysis, to ensure safe foraging and consumption.

In summary, mushroom classification is a detailed and scientific process that firmly places mushrooms within the fungal kingdom, separate from plants. By understanding their taxonomic hierarchy—from phyla like Basidiomycota to specific species—enthusiasts and researchers can accurately identify mushrooms and appreciate their ecological roles. Whether for culinary, medicinal, or conservation purposes, mastering mushroom classification basics is essential for anyone interested in these fascinating organisms.

Mushrooms: A Natural Remedy to Prevent Scurvy

You may want to see also

Fungal vs. Plant Characteristics

Mushrooms, including large ones, are not plants but fungi, belonging to a distinct kingdom in the biological classification system. This distinction is rooted in fundamental differences in their cellular structure, nutritional modes, and life cycles. Understanding these differences is crucial to appreciating why mushrooms are classified as fungi rather than plants.

Cellular Structure: One of the most significant differences between fungi and plants lies in their cellular composition. Plant cells are characterized by the presence of chloroplasts, rigid cell walls made of cellulose, and a large central vacuole. Chloroplasts enable plants to perform photosynthesis, converting sunlight into energy. In contrast, fungal cells, including those of mushrooms, lack chloroplasts and have cell walls composed of chitin, a substance not found in plants. Fungi are heterotrophs, meaning they obtain nutrients by breaking down organic matter externally and then absorbing it, whereas plants are autotrophs, producing their own food through photosynthesis.

Nutritional Modes: The way fungi and plants acquire nutrients highlights another key difference. Plants, as autotrophs, synthesize their food using sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide. This process not only sustains the plant but also forms the base of most food chains. Fungi, however, are primarily saprophytic, decomposing dead organic material to extract nutrients. Some fungi form symbiotic relationships with plants (mycorrhizae) or become parasitic, but none produce their own food like plants do. Mushrooms, as the fruiting bodies of fungi, play a role in spore dispersal rather than nutrient acquisition, further distinguishing them from plants.

Life Cycles and Reproduction: The life cycles and reproductive strategies of fungi and plants also differ markedly. Plants typically have a life cycle that includes alternation of generations, with distinct sporophyte and gametophyte phases. Reproduction can be sexual or asexual, often involving seeds or spores produced by the parent plant. Fungi, on the other hand, reproduce primarily through spores, which are dispersed into the environment to grow into new fungal organisms. The mushroom itself is a reproductive structure, producing and releasing spores to propagate the fungus. Unlike plants, fungi do not have a generational alternation, and their life cycle is generally simpler, focusing on spore production and dispersal.

Ecological Roles: While both fungi and plants play critical roles in ecosystems, their functions differ. Plants are primary producers, forming the foundation of food webs by converting inorganic materials into organic compounds. Fungi, particularly mushrooms, are decomposers, breaking down complex organic materials into simpler substances that can be recycled within the ecosystem. This decomposition process is vital for nutrient cycling and soil health. Additionally, fungi form extensive underground networks (mycelium) that can connect plants, facilitating nutrient exchange and communication between them, a role that plants do not play.

In summary, the classification of mushrooms as fungi rather than plants is based on clear biological distinctions, including differences in cellular structure, nutritional modes, life cycles, and ecological roles. Recognizing these differences not only clarifies the taxonomic placement of mushrooms but also highlights the unique contributions of fungi to the natural world.

Mushrooms: A Profitable and Sustainable Crop

You may want to see also

Cell Structure Differences

Mushrooms, often mistaken for plants due to their visible above-ground structures, are actually fungi. This distinction is primarily based on their cellular and structural differences. Unlike plants, which have complex, multicellular structures with specialized tissues for photosynthesis, fungi like mushrooms have a simpler cellular organization. The most fundamental difference lies in the cell walls: plant cells have cell walls made of cellulose, while fungal cells, including those of mushrooms, have cell walls composed of chitin, a substance also found in the exoskeletons of insects and crustaceans.

Another critical cell structure difference is the absence of chloroplasts in fungal cells. Plants contain chloroplasts, which are essential for photosynthesis, allowing them to produce energy from sunlight. Mushrooms, being fungi, lack chloroplasts and are heterotrophic, meaning they obtain nutrients by breaking down organic matter in their environment. This fundamental difference in energy acquisition highlights the distinct evolutionary paths of plants and fungi.

The internal organization of cells also differs significantly. Plant cells are eukaryotic and contain membrane-bound organelles, including a large central vacuole for storage and structural support. Fungal cells, while also eukaryotic, have a different arrangement of organelles and typically lack a large central vacuole. Instead, fungi often have smaller vacuoles and a more dispersed cytoplasm, reflecting their role in absorbing nutrients from their surroundings rather than storing resources internally.

Furthermore, the mode of cell division varies between plants and fungi. Plants primarily undergo cell division through mitosis, which involves the formation of a cell plate to separate daughter cells. Fungi, including mushrooms, divide through a process called septation, where a septum forms between cells, or through budding, where a new cell grows out of an existing one. This difference in cell division mechanisms underscores the unique growth patterns observed in fungi compared to plants.

Lastly, the structure of the plasma membrane differs between plant and fungal cells. Plant cell membranes are characterized by the presence of sterols like sitosterol, which contribute to membrane stability. In contrast, fungal cell membranes contain ergosterol, a unique sterol that plays a crucial role in maintaining membrane fluidity and function. This distinction in membrane composition is a key factor in the classification of mushrooms as fungi rather than plants.

In summary, the cell structure differences between large mushrooms and plants are profound and multifaceted. From the composition of cell walls and the absence of chloroplasts to variations in organelle arrangement, cell division, and membrane composition, these differences clearly delineate mushrooms as fungi rather than plants. Understanding these cellular distinctions is essential for appreciating the unique biology and ecological roles of mushrooms in contrast to their plant counterparts.

Alcohol and Microdosing: A Risky Mix?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Nutrient Acquisition Methods

Mushrooms, including large varieties, are not plants but fungi, belonging to the kingdom Fungi. Unlike plants, which produce their own food through photosynthesis, fungi lack chlorophyll and must acquire nutrients externally. This fundamental difference drives the unique nutrient acquisition methods of mushrooms. Fungi have evolved specialized structures and processes to obtain nutrients from their environment, primarily through absorption rather than ingestion. Understanding these methods is crucial to appreciating the ecological role of mushrooms and their distinct biological classification.

One of the primary nutrient acquisition methods of mushrooms is through their extensive network of thread-like structures called hyphae, which collectively form the mycelium. The mycelium acts as the "root system" of the fungus, secreting enzymes that break down complex organic matter, such as dead plant material, into simpler compounds. These compounds are then absorbed directly through the cell walls of the hyphae. This process, known as extracellular digestion, allows mushrooms to extract nutrients like carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus from their surroundings. The efficiency of this system enables fungi to thrive in diverse environments, from forest floors to decaying wood.

Another key method of nutrient acquisition in mushrooms is their symbiotic relationships with other organisms, particularly plants. In mycorrhizal associations, fungal hyphae form a mutualistic bond with plant roots, enhancing the plant’s ability to absorb water and nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen. In return, the fungus receives carbohydrates produced by the plant through photosynthesis. This symbiotic relationship is essential for the health of many ecosystems, as it supports plant growth and nutrient cycling. Large mushrooms, such as those in the genus *Amanita* or *Boletus*, often participate in these mycorrhizal networks, highlighting their ecological significance.

Saprotrophic fungi, which include many mushroom species, play a critical role in nutrient acquisition by decomposing dead organic material. These fungi secrete enzymes that break down complex substances like cellulose and lignin, which are indigestible to most organisms. By recycling nutrients from decaying matter, saprotrophic mushrooms contribute to the nutrient cycle, making essential elements available to other organisms in the ecosystem. This process is particularly important in forests, where mushrooms help return nutrients to the soil, supporting the growth of new plants.

In addition to these methods, some mushrooms acquire nutrients through parasitic or predatory means. Parasitic fungi infect living hosts, such as plants or insects, and extract nutrients directly from their tissues. Predatory fungi, though less common, trap and digest small organisms like nematodes using specialized structures. While these methods are less prevalent among large mushrooms, they demonstrate the versatility of fungal nutrient acquisition strategies. Overall, the diverse and efficient methods by which mushrooms acquire nutrients underscore their classification as fungi, distinct from plants, and their vital role in ecosystem functioning.

Mushroom Allergies: Fact or Fiction?

You may want to see also

Reproduction Mechanisms Compared

Mushrooms, often mistaken for plants due to their stationary nature and visible structures, are actually fungi. Unlike plants, which belong to the kingdom Plantae, mushrooms are part of the kingdom Fungi. This fundamental difference is rooted in their cellular structure, nutritional methods, and, most notably, their reproduction mechanisms. While plants primarily reproduce through seeds and flowers, fungi like mushrooms employ spores as their main reproductive units. Understanding these reproductive mechanisms highlights the distinct biological processes that separate mushrooms from plants.

Plants reproduce through a combination of sexual and asexual methods. Sexual reproduction involves the fusion of male and female gametes, typically facilitated by pollinators, leading to the formation of seeds within fruits. Asexual reproduction in plants occurs through methods like vegetative propagation, where new plants grow from roots, stems, or leaves of the parent plant. These processes are dependent on specialized structures like flowers, seeds, and roots, which are absent in fungi. In contrast, mushrooms lack these structures and rely entirely on spores for reproduction.

Fungi, including mushrooms, reproduce primarily through spores, which are microscopic, single-celled structures produced in vast quantities. These spores are dispersed through air, water, or animals and can remain dormant until conditions are favorable for growth. Mushroom spores are generated in the gills or pores located on the underside of the cap. When mature, the spores are released and can travel great distances, germinating to form new fungal colonies. This method of reproduction is highly efficient and allows fungi to thrive in diverse environments, from forest floors to decaying matter.

Another key difference lies in the life cycles of plants and fungi. Plants follow a sporophyte-gametophyte alternation of generations, where the sporophyte (diploid) phase is dominant, and the gametophyte (haploid) phase is reduced. In contrast, most fungi, including mushrooms, exhibit a haploid-dominant life cycle, where the majority of the life cycle is spent in the haploid phase. The diploid phase in fungi is brief and occurs only during the fusion of haploid cells (gametes) to form a zygote, which then undergoes meiosis to return to the haploid state. This fundamental difference in life cycles underscores the unique reproductive strategies of fungi compared to plants.

Furthermore, while plants require sunlight for photosynthesis to produce energy, fungi like mushrooms are heterotrophs, obtaining nutrients by decomposing organic matter. This distinction influences their reproductive strategies, as fungi do not need to invest energy in structures like leaves or flowers. Instead, they allocate resources to producing spores, which are lightweight and easily dispersed. This efficiency in reproduction allows fungi to colonize environments where plants cannot survive, such as dark, nutrient-poor substrates.

In summary, the reproduction mechanisms of mushrooms and plants reveal their distinct biological identities. Plants rely on seeds, flowers, and vegetative propagation, while mushrooms depend on spores and a haploid-dominant life cycle. These differences not only clarify why mushrooms are classified as fungi rather than plants but also highlight the evolutionary adaptations that enable fungi to thrive in diverse ecosystems. Understanding these mechanisms provides valuable insights into the unique roles fungi play in the natural world.

Mushroom Mystery: Are Outback Mushrooms Keto-Friendly?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Large mushrooms are classified as fungi, not plants. They belong to the kingdom Fungi, which is distinct from the kingdom Plantae.

Mushrooms are not considered plants because they lack chlorophyll and cannot perform photosynthesis. Instead, they obtain nutrients by decomposing organic matter, a characteristic of fungi.

While mushrooms and plants both grow in soil, they differ fundamentally. Plants produce their own food through photosynthesis, whereas mushrooms rely on absorbing nutrients from their environment.

Yes, large mushrooms, mold, and yeast are all part of the kingdom Fungi. They share common traits, such as cell walls made of chitin and a heterotrophic mode of nutrition.

Biologically, large mushrooms are not vegetables since they are fungi. However, in culinary contexts, they are often treated as vegetables due to their texture and versatility in cooking.