Morels, often hailed as a delicacy in the culinary world, are a subject of intrigue among mycologists and enthusiasts alike, particularly when it comes to their classification. The question of whether morels are a true mushroom hinges on the definition of the term. In a broad sense, morels are indeed fungi, characterized by their distinctive honeycomb-like caps and hollow stems. However, in a stricter taxonomic context, the term true mushroom typically refers to members of the order Agaricales, which includes common mushrooms like button mushrooms and portobellos. Morels, belonging to the order Pezizales, fall outside this category. Despite this technical distinction, morels are widely recognized and celebrated as mushrooms in both culinary and cultural contexts, blurring the lines between scientific classification and common usage.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Scientific Classification | Kingdom: Fungi, Phylum: Ascomycota, Class: Pezizomycetes, Order: Pezizales, Family: Morchellaceae, Genus: Morchella |

| True Mushroom Status | Yes, morels are considered true mushrooms as they belong to the Fungi kingdom and produce fruiting bodies (ascocarps) that are distinct from other fungal structures like molds or yeasts. |

| Fruiting Body Type | Ascomata (sac-like structures containing asci, which in turn contain ascospores) |

| Cap Shape | Conical or oval with a honeycomb-like appearance due to ridges and pits |

| Cap Color | Varies from yellow, tan, brown, to black, depending on the species |

| Stem Structure | Hollow, often lighter in color than the cap, and typically longer than the cap |

| Spore Type | Ascospores (produced within asci) |

| Spore Color | Cream to yellow, depending on the species |

| Habitat | Found in wooded areas, often near deciduous trees like ash, elm, and oak |

| Season | Typically spring, depending on geographic location |

| Edibility | Edible and highly prized when cooked properly; raw or undercooked morels can cause gastrointestinal distress |

| Toxicity | Some species may cause allergic reactions in sensitive individuals; proper identification is crucial |

| Ecological Role | Saprotrophic or symbiotic, depending on the species and environment |

| Common Species | Morchella esculenta (yellow morel), Morchella elata (black morel), and others |

| Conservation Status | Not typically listed as endangered, but overharvesting can impact local populations |

| Culinary Use | Used in gourmet cooking for their unique flavor and texture |

| Foraging Difficulty | Moderate; requires knowledge to distinguish from false morels (Gyromitra species), which are toxic |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Morel Classification: Are morels fungi or something else Their taxonomic placement explained

- True Mushroom Criteria: Defining true mushrooms: gills, spores, and mycelium structure

- Morel Anatomy: Examining morel features: honeycomb caps, hollow stems, and spore release

- Edibility vs. True Mushroom: Being edible doesn’t define a true mushroom; biology does

- Morels vs. False Mushrooms: Comparing morels to look-alikes like false morels and verpa

Morel Classification: Are morels fungi or something else? Their taxonomic placement explained

Morels, with their honeycomb caps and earthy flavor, are undeniably fungi. But where exactly do they fit in the fungal family tree? The answer lies in their taxonomic classification, a system that groups organisms based on shared characteristics and evolutionary relationships.

Morels belong to the kingdom Fungi, a diverse group of organisms distinct from plants and animals. Within this kingdom, they fall under the phylum Ascomycota, characterized by their method of spore production. Ascomycetes, as they're called, form spores within sac-like structures called asci. This places morels in a group that includes truffles, cup fungi, and even common molds like Penicillium.

Narrowing it down further, morels belong to the order Pezizales, known for their cup-like or saddle-shaped fruiting bodies. Finally, they are classified within the family Morchellaceae, a group of fungi sharing similar morphological and genetic traits. This precise classification reflects our growing understanding of fungal diversity and evolutionary history.

Understanding morel classification isn't just academic. It has practical implications for foragers and enthusiasts. Knowing their taxonomic placement helps identify morels accurately, distinguishing them from potentially toxic lookalikes. It also sheds light on their ecological role as decomposers, breaking down organic matter and contributing to nutrient cycling in forests.

While morels may seem like a culinary delicacy, their classification reveals a fascinating story of evolution and ecological interconnectedness. By understanding their place in the fungal kingdom, we gain a deeper appreciation for these enigmatic mushrooms and their vital role in the natural world.

Denver Decriminalizes Magic Mushrooms: Law and Future

You may want to see also

True Mushroom Criteria: Defining true mushrooms: gills, spores, and mycelium structure

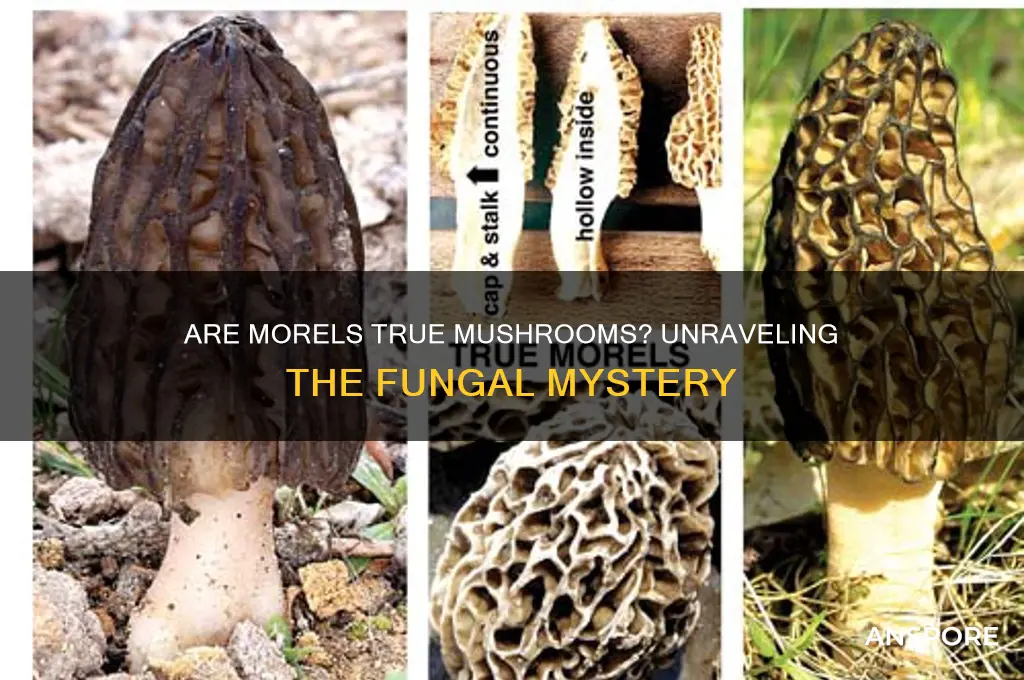

Morels, with their honeycomb caps and earthy flavor, are often celebrated as a culinary delicacy. But do they meet the strict criteria to be classified as true mushrooms? To answer this, we must examine three key anatomical features: gills, spores, and mycelium structure. These elements are the cornerstone of fungal taxonomy, distinguishing true mushrooms from look-alikes.

Gills: The Absence of a Defining Feature

True mushrooms typically possess gills—thin, blade-like structures beneath the cap where spores are produced. Morels, however, lack gills entirely. Instead, they have a network of ridges and pits (called "ascocarps") that serve a similar spore-dispersal function. This absence of gills might initially disqualify morels, but it’s not the sole criterion. For example, truffles also lack gills yet are classified as fungi, albeit not mushrooms. The takeaway? Gills are a common but not mandatory trait for true mushrooms.

Spores: A Microscopic Signature

Spores are the reproductive units of fungi, and their structure is critical for classification. True mushrooms produce spores externally on gills or pores. Morels, however, produce spores internally within their ascocarps, releasing them through tiny openings. This method, known as "ascospore" production, is unique to the Ascomycota phylum, while most mushrooms belong to the Basidiomycota phylum. Despite this difference, morels’ spore-producing mechanism is highly efficient, ensuring their survival in diverse environments. Thus, while their spore structure differs, it doesn’t disqualify them from being considered true mushrooms.

Mycelium Structure: The Hidden Foundation

Beneath the soil, the mycelium—a network of thread-like filaments—is the lifeblood of any fungus. True mushrooms have a mycelium that forms a symbiotic relationship with their environment, often decomposing organic matter. Morels’ mycelium behaves similarly, breaking down wood and soil nutrients. This shared function aligns morels with true mushrooms, despite differences in above-ground structures. Practical tip: Cultivating morels requires mimicking their natural mycelium habitat, such as using wood chips or soil rich in organic matter.

While morels lack gills and produce spores differently, their mycelium structure and ecological role mirror those of true mushrooms. Taxonomy is not rigid but evolves with scientific understanding. Morels, though distinct, fit the broader definition of mushrooms as fleshy, spore-producing fungi. For foragers and chefs alike, this means morels remain a prized find, both in the wild and on the plate.

Mushroom Hunting Season: When to Start Foraging

You may want to see also

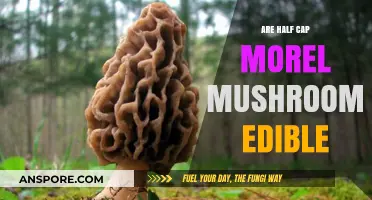

Morel Anatomy: Examining morel features: honeycomb caps, hollow stems, and spore release

Morels, with their distinctive honeycomb caps, are often the centerpiece of discussions about whether they qualify as "true mushrooms." Unlike the smooth, gill-laden caps of button mushrooms, morels feature a network of ridges and pits that resemble a natural honeycomb. This unique structure isn’t just aesthetic—it serves a critical function in spore dispersal. The ridges increase surface area, allowing spores to be released more efficiently into the air. This adaptation highlights morels’ evolutionary sophistication, aligning them firmly within the fungal kingdom despite their unconventional appearance.

The hollow stem of a morel is another defining feature that sets it apart from other fungi. While many mushrooms have solid or fleshy stems, morels’ stems are hollow from base to cap, creating a lightweight yet sturdy structure. This design reduces the mushroom’s energy expenditure while maintaining its form, a testament to nature’s efficiency. For foragers, this characteristic is a key identifier, though caution is advised: false morels often have partially filled stems, a critical distinction to avoid toxic lookalikes.

Spore release in morels is a fascinating process tied directly to their anatomy. As the honeycomb cap matures, it produces spores within its pits. When disturbed by wind, rain, or even passing animals, these spores are dislodged and carried away, ensuring the species’ propagation. Unlike mushrooms with gills that release spores passively, morels rely on external forces, making their spore-bearing structures both fragile and functional. Foraging at the right time—when caps are fully developed but not yet dry—maximizes the chances of witnessing this natural mechanism in action.

Understanding morel anatomy isn’t just academic—it’s practical for foragers and chefs alike. The honeycomb cap, for instance, can trap dirt and debris, requiring thorough cleaning before cooking. Submerging morels in cold water for 10–15 minutes allows sediment to settle without compromising their texture. Similarly, the hollow stem’s delicate structure means morels should be handled gently to avoid breakage. Whether sautéing, drying, or preserving, respecting these anatomical features ensures both safety and culinary excellence.

In the debate over whether morels are "true mushrooms," their anatomy provides compelling evidence. The honeycomb cap, hollow stem, and spore release mechanism are not anomalies but adaptations that underscore their fungal identity. These features distinguish morels not as outliers, but as specialized members of the mushroom family, offering both ecological and culinary value. By examining their structure, we gain not only knowledge but also a deeper appreciation for these elusive forest treasures.

Mushrooms: Carb and Sugar Content Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Edibility vs. True Mushroom: Being edible doesn’t define a true mushroom; biology does

Morels, with their honeycomb caps and earthy flavor, are prized by foragers and chefs alike. Yet, their classification as "true mushrooms" often hinges on a common misconception: if it’s edible, it must be a mushroom. This oversimplification ignores the biological complexity that defines fungi. True mushrooms belong to the phylum Basidiomycota and produce spores under a gill structure, among other criteria. Morels, scientifically classified as *Morchella*, indeed meet these criteria, making them true mushrooms despite the widespread confusion. Edibility, while a valuable trait, is a culinary concern, not a taxonomic one.

Consider the case of the false morel (*Gyromitra esculenta*), a toxic look-alike often mistaken for its edible counterpart. While both are fungi, only the true morel fits the biological definition of a mushroom. False morels contain gyromitrin, a toxin that breaks down into monomethylhydrazine, a component of rocket fuel. Ingesting even small amounts—as little as 100 grams—can lead to severe symptoms like nausea, dizziness, and, in extreme cases, organ failure. This example underscores the danger of conflating edibility with classification. Foraging guides and mycologists stress the importance of identifying mushrooms based on spore structure, habitat, and other biological markers, not just their culinary potential.

To illustrate the distinction further, compare morels to another edible fungus, the lion’s mane (*Hericium erinaceus*). Lion’s mane is not a true mushroom because it lacks the typical cap-and-stem structure and produces spores on teeth-like projections. Yet, it’s highly prized for its health benefits, including potential neuroprotective effects when consumed in doses of 500–3,000 mg daily in supplement form. This example highlights how edibility and biological classification are independent factors. A fungus can be both non-mushroom and edible, just as a true mushroom can be inedible or toxic.

For foragers, the takeaway is clear: biology, not edibility, defines a true mushroom. Always verify spore-bearing structures—gills, pores, or ridges—and consult field guides or experts. Morel hunters, for instance, should look for the hollow stem and ridged, honeycomb cap characteristic of *Morchella*. Avoid relying on taste or smell, as toxic species can mimic these traits. Remember, while morels are both edible and true mushrooms, not all edible fungi meet the biological criteria, and not all true mushrooms are safe to eat. The distinction is not just academic—it’s a matter of safety and scientific accuracy.

Mushroom Lovers: How Many of Us Are There?

You may want to see also

Morels vs. False Mushrooms: Comparing morels to look-alikes like false morels and verpa

Morels, with their honeycomb caps and earthy flavor, are a forager’s prize, but not all mushrooms that resemble them are safe to eat. False morels, particularly species like *Gyromitra esculenta*, contain gyromitrin, a toxin that breaks down into monomethylhydrazine, a component of rocket fuel. Ingesting even small amounts can lead to symptoms like nausea, dizziness, and in severe cases, organ failure. Verpa bohemica, another look-alike, has a cap that hangs freely from the stem, unlike the morel’s attached cap, and its hollow stem is a giveaway. Knowing these distinctions is critical, as misidentification can turn a gourmet meal into a medical emergency.

To safely distinguish morels from their dangerous doppelgängers, start by examining the cap and stem structure. True morels have a sponge-like cap with pits and ridges that attach directly to the stem, while false morels often have a wrinkled, brain-like cap that sits atop the stem. Verpa species have a distinct cap that hangs like an umbrella, unattached to the stem. Another key feature is the stem: morels have a completely hollow stem, whereas false morels and verpa have stems that are either partially filled or completely solid. Always cut the mushroom in half lengthwise to confirm these characteristics before consumption.

If you’re new to foraging, start by joining a local mycological society or attending a guided mushroom hunt. Experienced foragers can provide hands-on training and help you build confidence in identifying morels. Avoid relying solely on online images, as lighting and angles can distort features. Instead, invest in a field guide specific to your region, such as *Mushrooms of the Northeast* by Teresa Marrone, which includes detailed descriptions and comparisons of morels and their look-alikes. Remember, when in doubt, throw it out—no meal is worth risking your health.

Cooking morels properly is another layer of safety. While true morels are safe to eat when cooked, false morels require additional steps to remove toxins, though even this is not foolproof. To prepare morels, soak them in cold water for 10–15 minutes to remove dirt and debris, then sauté them in butter or oil until they’re fully cooked. Avoid eating large quantities in one sitting, as even true morels can cause mild digestive upset in some individuals. Pairing them with rich sauces or incorporating them into dishes like risotto or omelets can enhance their flavor while ensuring a balanced meal.

Finally, consider the ethical and environmental aspects of foraging. Morels are a springtime delicacy, often found in wooded areas with deciduous trees like elm, ash, and poplar. Harvest sustainably by using a knife to cut the mushroom at the base, leaving the mycelium intact to regrow. Avoid over-harvesting from a single area, and always ask for permission when foraging on private land. By respecting nature and honing your identification skills, you can enjoy the thrill of finding morels while minimizing risks to yourself and the ecosystem.

Mastering Mushroom Identification: A Guide to Recognizing Genera

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, morels are classified as true mushrooms. They belong to the phylum Basidiomycota and are part of the kingdom Fungi, meeting the criteria for true mushrooms.

Morels are true mushrooms because they produce spores from club-like structures called basidia, a defining characteristic of the Basidiomycota group, which includes most edible mushrooms.

While morels are true mushrooms, there are false morels (Gyromitra species) that resemble them but belong to the Ascomycota phylum. These are not considered true mushrooms and can be toxic if not properly prepared.