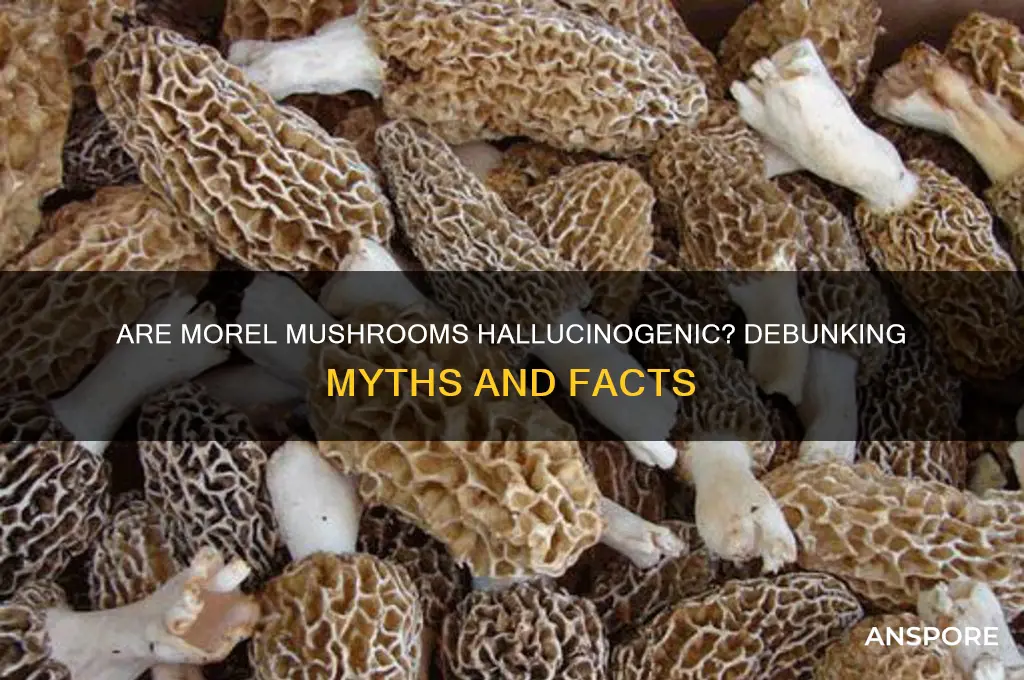

Morel mushrooms, prized for their earthy flavor and distinctive honeycomb appearance, are a delicacy in culinary circles, but questions often arise about their potential hallucinogenic properties. While morels are generally considered safe to eat and are not classified as hallucinogenic, there is some confusion due to their distant relation to certain psychoactive fungi, such as the *False Morel* (*Gyromitra esculenta*), which contains toxins that can cause severe illness if not properly prepared. True morels (*Morchella* species) do not contain hallucinogenic compounds like psilocybin, found in magic mushrooms, but it’s crucial to accurately identify them to avoid consuming toxic look-alikes. Always consult a knowledgeable forager or guide when harvesting wild mushrooms to ensure safety and clarity.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Hallucinogenic Properties | No, morel mushrooms are not hallucinogenic. |

| Psychoactive Compounds | Morels do not contain psilocybin, psilocin, or other known hallucinogenic compounds. |

| Edibility | Generally considered edible and highly prized in culinary use. |

| Toxicity | Some species can cause gastrointestinal upset if not cooked properly or consumed in large quantities. |

| Confusion with Other Mushrooms | Occasionally mistaken for false morels (Gyromitra species), which can be toxic if not prepared correctly. |

| Scientific Classification | Kingdom: Fungi, Division: Ascomycota, Genus: Morchella. |

| Common Uses | Culinary ingredient in soups, sauces, and other dishes. |

| Foraging Caution | Proper identification is crucial to avoid toxic look-alikes. |

| Medicinal Properties | Limited research, but some studies suggest potential antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. |

| Legal Status | Legal to forage and consume in most regions, but regulations vary by location. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Morel vs. False Morel Identification

Morels and false morels may share a resemblance, but their differences are critical, especially when considering the question of hallucinogenic properties. While true morels (Morchella spp.) are prized for their earthy flavor and safe consumption, false morels (Gyromitra spp.) contain a toxin called gyromitrin, which can cause severe gastrointestinal distress, neurological symptoms, and even death if ingested in sufficient quantities. Contrary to popular belief, neither true nor false morels are hallucinogenic in the traditional sense, though gyromitrin poisoning can cause disorientation and confusion, which might be misconstrued as hallucinogenic effects.

Identification begins with structure. True morels have a honeycomb-like cap with pits and ridges, resembling a sponge, while false morels have a brain-like, wrinkled, or folded cap with a more convoluted appearance. When sliced, a true morel’s hollow stem connects directly to the cap, forming a seamless, hollow chamber. False morels, however, often have a cottony or substantial interior and may not be entirely hollow. This structural difference is a key field identifier, but it’s not foolproof—always cross-reference with other characteristics.

Color and habitat play secondary roles. True morels are typically brown, gray, or yellow, while false morels can be reddish-brown, purplish, or dark brown. True morels often grow in wooded areas, particularly near ash, elm, or poplar trees, whereas false morels are more commonly found in coniferous forests. However, habitat alone is insufficient for identification; false morels can occasionally appear in similar environments, making visual inspection essential.

Preparation methods are crucial for false morels. If misidentified, false morels must be thoroughly cooked to hydrolyze gyromitrin into monomethylhydrazine, a toxic compound. Boiling in water for at least 20 minutes, discarding the liquid, and repeating the process can reduce toxicity, but even then, consumption is risky. True morels, on the other hand, require minimal preparation—a quick sauté or blanch suffices to retain their delicate flavor.

The takeaway is clear: certainty saves lives. If there’s any doubt, discard the mushroom. Relying on apps or inexperienced foragers can be dangerous; instead, consult a mycologist or a detailed field guide. While neither morel nor false morel is hallucinogenic, the consequences of misidentification are far more severe than a psychedelic experience—they can be fatal. Always prioritize safety over curiosity in the world of wild mushrooms.

Mushrooms and Sun-Dried Tomatoes: A Flavorful Culinary Match?

You may want to see also

Psychoactive Compounds in Mushrooms

Morel mushrooms, prized for their earthy flavor and distinctive honeycomb caps, are not known to contain psychoactive compounds. Unlike their distant relatives, psilocybin mushrooms, morels lack the chemical constituents that induce hallucinations. However, the broader world of fungi is rich with psychoactive compounds, each with unique effects and risks. Understanding these substances is crucial for anyone exploring the intersection of mushrooms and altered states of consciousness.

Among the most well-known psychoactive compounds in mushrooms is psilocybin, found in over 200 species of the genus *Psilocybe*. When ingested, psilocybin is metabolized into psilocin, which binds to serotonin receptors in the brain, producing hallucinations, altered perception, and profound emotional experiences. A typical recreational dose ranges from 1 to 3 grams of dried mushrooms, though effects vary widely based on individual tolerance and mushroom potency. Psilocybin’s therapeutic potential is currently under study for treating depression, anxiety, and PTSD, with clinical trials showing promise in controlled settings.

Another psychoactive compound, amanitin, found in the deadly *Amanita* species, is not hallucinogenic but highly toxic. Mistaking these mushrooms for edible varieties can lead to severe liver and kidney damage, often fatal. This underscores the importance of accurate identification when foraging. Unlike psilocybin, amanitin has no therapeutic value and serves as a stark reminder of the dangers lurking in the fungal kingdom.

Beyond psilocybin and amanitin, other compounds like muscimol (found in *Amanita muscaria*) and ibotenic acid produce sedative and hallucinogenic effects, though their use is less common due to unpredictable outcomes and potential toxicity. Muscimol acts on GABA receptors, causing drowsiness, confusion, and vivid dreams. A safe dosage is difficult to determine, as potency varies widely between specimens, making experimentation risky.

For those interested in exploring psychoactive mushrooms, education and caution are paramount. Misidentification can lead to poisoning, and even known species like psilocybin mushrooms carry legal and psychological risks. Always consult reliable guides, avoid foraging unless expertly trained, and consider the legal and ethical implications of use. While morels remain a culinary delight, their psychoactive cousins demand respect and informed decision-making.

Magic Mushrooms: The Science Behind Hallucinogens

You may want to see also

Toxicity Risks of Misidentification

Morel mushrooms, prized for their earthy flavor and distinctive honeycomb caps, are not hallucinogenic. However, their allure often leads foragers into perilous territory. Misidentification is a critical risk, as morels resemble toxic species like the false morel (*Gyromitra esculenta*) and the early false morel (*Verpa bohemica*). These look-alikes contain gyromitrin, a toxin that breaks down into monomethylhydrazine, a compound used in rocket fuel. Ingesting even small amounts can cause severe symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and in extreme cases, liver failure or death.

To avoid misidentification, foragers must adhere to strict guidelines. First, examine the mushroom’s cap structure: true morels have a honeycomb pattern with pits and ridges, while false morels have a wrinkled, brain-like appearance. Second, inspect the stem: morels have a hollow stem that fuses seamlessly with the cap, whereas false morels often have a skirt-like ring or a distinct cap-stem separation. Third, always cook morels thoroughly, as heat breaks down any trace toxins. However, cooking does not neutralize gyromitrin in false morels, making proper identification non-negotiable.

The consequences of misidentification are not limited to physical toxicity. Psychological distress can arise from the fear of poisoning, especially for novice foragers. A single mistake can tarnish the reputation of mushroom hunting, deterring others from this rewarding activity. To mitigate this, foragers should consult field guides, join local mycological societies, and cross-reference findings with expert resources. Smartphone apps, while convenient, are not infallible and should supplement, not replace, traditional methods.

Children and pets are particularly vulnerable to misidentification risks. Their smaller body mass means even a tiny dose of toxins can be lethal. Foragers with children or pets should never collect mushrooms in areas accessible to them and should educate family members about the dangers of wild mushrooms. If ingestion is suspected, seek immediate medical attention, bringing a sample of the mushroom for identification. Time is critical, as symptoms can appear within hours.

In conclusion, while morels are not hallucinogenic, their toxic doppelgängers pose a grave threat. Misidentification is avoidable with careful observation, education, and caution. Foraging should be a mindful practice, balancing the thrill of discovery with the responsibility of safety. By respecting these principles, enthusiasts can enjoy morels without falling prey to their dangerous look-alikes.

Chipotle Peppers in Sauce: A Perfect Match for Mushrooms?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Historical Use of Hallucinogenic Fungi

Morel mushrooms, prized for their earthy flavor and distinctive honeycomb caps, are not hallucinogenic. Their historical use lies firmly in the culinary realm, not the psychedelic. However, the question of hallucinogenic fungi opens a door to a rich and complex history of human interaction with mind-altering substances.

While morels offer a gourmet experience, other fungi have been revered and feared for their ability to alter consciousness.

Consider the *Psilocybe* genus, containing species like *Psilocybe cubensis* and *Psilocybe semilanceata*, commonly known as "magic mushrooms." These fungi have been used for millennia in various cultures for spiritual, divinatory, and healing purposes. Anthropological evidence suggests that indigenous peoples in Mesoamerica, such as the Aztecs and Mayans, consumed psilocybin mushrooms in sacred rituals, believing they facilitated communication with deities and provided access to hidden knowledge.

The dosage for these experiences was often carefully controlled, with shamans or spiritual leaders guiding the ceremony and interpreting the visions.

The historical use of hallucinogenic fungi wasn't limited to the Americas. In Siberia, the Koryak people traditionally consumed *Amanita muscaria*, a brightly colored mushroom containing muscimol and ibotenic acid. Their rituals involved ingesting the mushroom to induce a trance-like state, believed to connect them with the spirit world and enhance hunting prowess. It's important to note that *Amanita muscaria* is highly toxic and requires careful preparation to minimize its harmful effects.

Unlike the more controlled doses of psilocybin mushrooms, *Amanita* consumption often resulted in unpredictable and potentially dangerous experiences.

The historical record also hints at the use of hallucinogenic fungi in ancient Europe. Rock art and archaeological findings suggest that certain mushroom species may have played a role in the spiritual practices of Neolithic cultures. However, the specific species and their methods of use remain shrouded in mystery. This ambiguity highlights the challenges of reconstructing ancient practices based on limited evidence.

The historical use of hallucinogenic fungi offers a fascinating glimpse into the diverse ways humans have sought to alter their consciousness and connect with the world around them. While morels remain firmly in the culinary domain, the study of these other fungi provides valuable insights into the cultural, spiritual, and potentially therapeutic aspects of psychoactive substances.

Finding Magic Mushrooms in Timber Sales

You may want to see also

Edible Morel Safety Guidelines

Morel mushrooms, prized for their earthy flavor and unique honeycomb appearance, are generally considered safe to eat when properly identified and prepared. However, confusion with toxic look-alikes, such as false morels, can lead to severe illness. To ensure safety, always cross-reference your find with multiple reliable guides or consult an experienced forager. Misidentification is the primary risk, not hallucinogenic properties, as true morels do not contain psychoactive compounds.

Proper preparation is equally critical. Morels should be thoroughly cooked before consumption to eliminate any trace toxins or harmful microorganisms. Raw morels can cause gastrointestinal distress, even if correctly identified. Sauté, fry, or boil them for at least 10–15 minutes to neutralize potential irritants. Avoid consuming large quantities in one sitting, as some individuals may experience mild sensitivity even to true morels. Start with a small portion to test tolerance, especially if it’s your first time eating them.

Storage practices also play a role in safety. Fresh morels should be consumed within a few days of harvesting or properly preserved. Drying is a popular method, as it extends shelf life and concentrates flavor. To dry morels, spread them out in a well-ventilated area or use a dehydrator at low heat. Once dried, store them in an airtight container in a cool, dark place. Rehydrate by soaking in warm water for 20–30 minutes before cooking, and always discard the soaking liquid to avoid potential contaminants.

Foraging responsibly is another key aspect of morel safety. Avoid collecting mushrooms near polluted areas, such as roadsides or industrial sites, as they can absorb toxins. Additionally, never consume alcohol while foraging, as impaired judgment increases the risk of misidentification. If you’re unsure about a find, err on the side of caution and leave it behind. Remember, the goal is to enjoy morels safely, not to take unnecessary risks.

Finally, educate yourself and others about morel safety. Attend local foraging workshops, join mycological societies, or invest in reputable field guides. Teaching proper identification and preparation techniques to fellow enthusiasts helps foster a safer foraging community. By combining knowledge, caution, and respect for nature, you can confidently enjoy the culinary delights of morels without compromising your health.

Steaming Mushrooms: The Art of Seasoning

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, morel mushrooms are not hallucinogenic. They are edible and prized for their unique flavor and texture, but they do not contain psychoactive compounds.

No, consuming true morel mushrooms will not cause hallucinations. However, misidentifying a toxic look-alike could lead to illness, so proper identification is crucial.

No, morel mushrooms do not contain psilocybin or any other hallucinogenic substances. They are safe to eat when correctly identified and prepared.

No, none of the true morel mushroom species (Morchella genus) are hallucinogenic. Hallucinogenic mushrooms belong to different genera, such as Psilocybe.