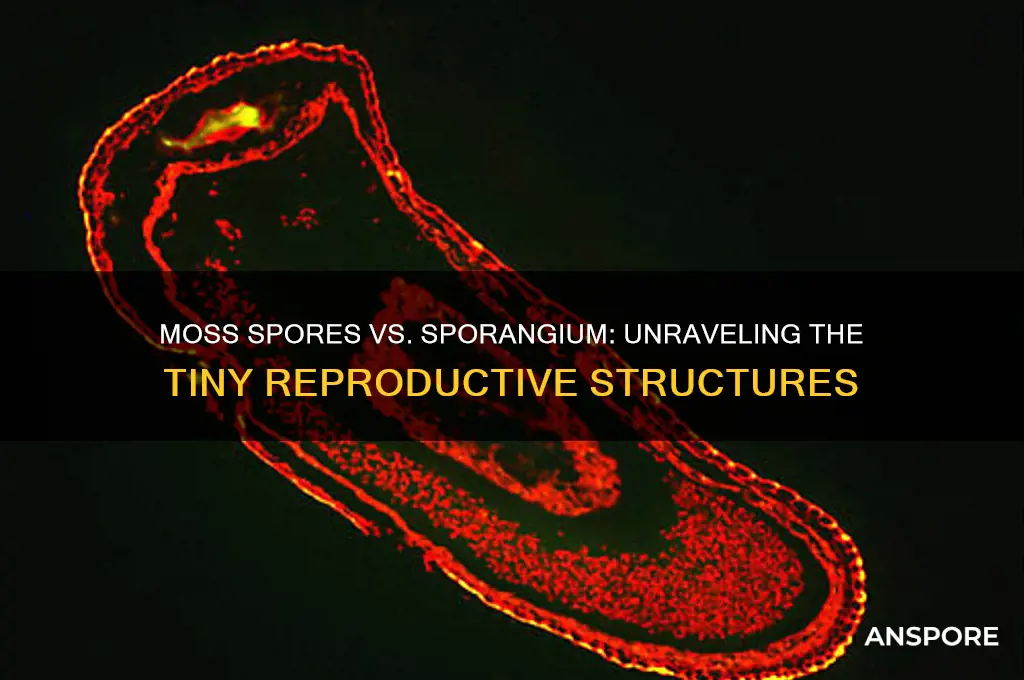

Mosses are non-vascular plants that reproduce both sexually and asexually, with their life cycle involving alternation of generations. One key aspect of their sexual reproduction is the production of spores within a structure called the sporangium. The sporangium is a capsule-like organ located at the tip of the moss's sporophyte, which develops after fertilization. Inside the sporangium, spores are formed through meiosis, and once mature, they are released into the environment to grow into new gametophyte plants. While the spores themselves are the reproductive units, the sporangium is the protective and dispersive structure that houses them. Therefore, moss spores are not the sporangium but rather the products contained within it, highlighting the distinction between the reproductive cells and the organ that produces and disperses them.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Moss spores are the reproductive units produced by moss plants, while a sporangium is the structure in which spores are produced and stored. |

| Location | Spores are found inside the sporangium, which is typically located at the tip of the seta (stalk) in moss plants. |

| Function | Spores are the means of asexual reproduction and dispersal in mosses, while the sporangium is the organ responsible for spore production and protection. |

| Structure | Spores are unicellular and often have a protective outer wall. The sporangium is a multicellular structure with a wall that opens to release spores. |

| Development | Spores develop within the sporangium through meiosis. Once mature, the sporangium dries and splits open to release the spores. |

| Dispersal | Spores are dispersed by wind, water, or animals after being released from the sporangium. |

| Life Cycle | In the moss life cycle, spores germinate into protonema (a thread-like structure), which then develops into the gametophyte (the dominant green plant body). |

| Taxonomy | Mosses belong to the division Bryophyta, and their sporangia are characteristic of non-vascular plants. |

| Size | Spores are microscopic (typically 10-50 μm), while the sporangium is visible to the naked eye (often 1-5 mm in length). |

| Shape | Spores are usually spherical or oval, while the sporangium is often capsule-like or spherical in shape. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporangium Structure: Moss sporangium is a capsule-like structure that produces and contains spores

- Spore Release Mechanism: Spores are released through a peristome or teeth-like structures in the sporangium

- Sporophyte Generation: The sporangium develops on the sporophyte, the diploid phase of moss

- Spore Dispersal Methods: Wind, water, and animals aid in dispersing moss spores from the sporangium

- Sporangium vs. Gametangia: Sporangium produces spores, while gametangia produce gametes in moss life cycles

Sporangium Structure: Moss sporangium is a capsule-like structure that produces and contains spores

The moss sporangium is a marvel of botanical engineering, a capsule-like structure that serves as the spore factory of the plant. This organ, typically found at the tip of the seta (stalk) in the sporophyte generation, is where the life cycle of mosses pivots from dependent to independent. Its structure is both simple and ingenious: a protective outer wall encases the spore-producing tissue, ensuring that the next generation is shielded until optimal dispersal conditions arise. This design is not just functional but also a testament to the evolutionary precision of non-vascular plants.

To understand the sporangium’s role, consider its developmental process. After fertilization, the sporophyte grows, and the sporangium differentiates into distinct layers: the jacket (outer protective layer), the amphithecium (middle layer), and the endothecium (inner spore-producing layer). Within the endothecium, spore mother cells undergo meiosis, producing haploid spores. These spores are not merely contained but are also strategically positioned for dispersal. The sporangium’s capsule-like shape, often reinforced with a lid-like operculum and a ring of teeth (the peristome), facilitates spore release through mechanisms like wind or raindrop impact.

Practical observation of moss sporangia can be a rewarding exercise for botanists and hobbyists alike. To examine one, collect a mature moss sporophyte with a visible sporangium, preferably from a species like *Sphagnum* or *Polytrichum*. Use a magnifying glass or low-power microscope to observe the capsule’s structure, noting the peristome teeth or operculum. For a deeper analysis, section the sporangium with a razor blade and mount it on a slide to view the internal layers under higher magnification. This hands-on approach not only reinforces theoretical knowledge but also highlights the sporangium’s role as a microcosm of moss reproduction.

Comparatively, the moss sporangium contrasts sharply with the sporangia of ferns or fungi, both in structure and function. While fern sporangia are often clustered on the underside of leaves, moss sporangia are terminal and singular, reflecting their simpler, non-vascular architecture. Fungal sporangia, on the other hand, are typically sac-like structures that release spores en masse, whereas moss sporangia release spores gradually through a regulated mechanism. This comparison underscores the sporangium’s specialization in mosses, tailored to their small size and habitat requirements.

In conclusion, the moss sporangium is more than a spore container; it is a sophisticated reproductive organ that encapsulates the plant’s survival strategy. Its capsule-like structure, layered organization, and dispersal mechanisms are adaptations honed over millennia, ensuring that mosses thrive in diverse environments. By studying the sporangium, we gain not just insight into moss biology but also a deeper appreciation for the ingenuity of nature’s designs. Whether for academic research or personal curiosity, understanding this structure opens a window into the intricate world of bryophytes.

Exploring the Microscopic World: What Does a Spore Really Look Like?

You may want to see also

Spore Release Mechanism: Spores are released through a peristome or teeth-like structures in the sporangium

Mosses, unlike vascular plants, rely on a unique and intricate mechanism for spore dispersal. At the heart of this process lies the sporangium, a capsule-like structure that houses the spores. However, the release of these spores is not a simple matter of the sporangium bursting open. Instead, mosses have evolved specialized structures known as peristomes or teeth-like appendages that regulate the release of spores in response to environmental conditions.

Consider the peristome, a ring of triangular teeth surrounding the sporangium opening. These teeth are hygroscopic, meaning they respond to changes in humidity. When the air is dry, the teeth curl inward, closing the sporangium and preventing spore release. Conversely, in humid conditions, the teeth swell and straighten, opening the sporangium and allowing spores to escape. This mechanism ensures that spores are dispersed when conditions are favorable for germination, such as after rainfall.

Teeth-like structures, found in some moss species, operate similarly but with a more rigid design. These structures act like a ratchet, gradually releasing spores as the sporangium dries out. For example, in the genus *Polytrichum*, the sporangium features a ring of teeth that open and close in response to moisture changes, releasing spores in small, controlled bursts. This gradual release increases the chances of spores landing in suitable habitats.

To observe this mechanism in action, collect a mature moss sporangium and place it under a microscope. Gradually increase the humidity around the sample using a spray bottle or damp paper towel. Note how the peristome or teeth respond, opening to reveal the spores within. For a more hands-on approach, collect moss samples from different environments (e.g., shaded vs. sunny areas) and compare the structure and behavior of their sporangia. This simple experiment highlights the adaptability of mosses to their surroundings.

Understanding the spore release mechanism through peristomes or teeth-like structures not only sheds light on moss biology but also has practical applications. For instance, this knowledge can inform conservation efforts by identifying optimal conditions for moss propagation. Additionally, the hygroscopic properties of peristomes inspire biomimetic designs in engineering, such as humidity-responsive materials. By studying these tiny structures, we gain insights into both the natural world and potential technological innovations.

Understanding Spore Production: Locations and Processes in Fungi and Plants

You may want to see also

Sporophyte Generation: The sporangium develops on the sporophyte, the diploid phase of moss

Mosses, often overlooked in the plant kingdom, exhibit a fascinating life cycle that hinges on the sporophyte generation. This phase is crucial for their reproduction, and it begins with the development of the sporangium on the sporophyte, the diploid stage of the moss. Unlike the gametophyte, which is haploid and more commonly observed as the green, carpet-like structure, the sporophyte is less conspicuous but equally vital. It arises from the fusion of gametes during fertilization, marking the start of a new reproductive journey.

The sporangium, a capsule-like structure, forms at the tip of the sporophyte. Its primary function is to produce and disperse spores, ensuring the continuation of the species. This process is highly regulated, with environmental cues such as humidity and light influencing the timing of spore release. For instance, in *Sphagnum* mosses, the sporangium, or capsule, dries out and splits open, ejecting spores with remarkable force. This mechanism highlights the adaptability of mosses to their often harsh environments, such as bogs and tundra.

Understanding the sporophyte generation is essential for anyone cultivating mosses, whether for conservation, landscaping, or scientific study. To encourage sporophyte development, maintain consistent moisture and provide adequate light, as these factors stimulate gametophyte maturation and fertilization. Once the sporophyte emerges, avoid physical disturbance, as the sporangium is delicate and easily damaged. For optimal spore collection, monitor the sporangium’s color change from green to brown, signaling maturity.

Comparatively, the sporophyte generation in mosses is shorter-lived than in ferns or flowering plants, reflecting their evolutionary position. While ferns and angiosperms rely on long-lived sporophytes for reproduction, mosses prioritize gametophytes, with sporophytes dependent on them for nutrients. This distinction underscores the unique ecological niche of mosses, thriving in environments where larger plants cannot survive. By studying this phase, we gain insights into plant evolution and the resilience of bryophytes in diverse ecosystems.

In practical terms, observing the sporophyte generation can be a rewarding experience for hobbyists and educators alike. To witness this stage, collect moss samples from their natural habitat and place them in a terrarium with controlled conditions. Mist the moss regularly to mimic its natural environment, and within weeks, you may observe the emergence of sporophytes. This hands-on approach not only deepens appreciation for moss biology but also fosters a connection to the intricate processes that sustain life on Earth.

Best Places to Buy Shroom Spores Online and Locally

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Spore Dispersal Methods: Wind, water, and animals aid in dispersing moss spores from the sporangium

Moss spores, housed within the sporangium, rely on external forces for dispersal, ensuring the survival and propagation of these ancient plants. Wind, water, and animals each play distinct roles in this process, showcasing the adaptability of mosses to diverse environments. Wind, the most common disperser, carries lightweight spores over vast distances, often aided by the sporangium’s elevated position on the seta. This method is particularly effective in open habitats where air currents are strong and consistent. For instance, *Sphagnum* mosses, thriving in peatlands, release spores that can travel kilometers, colonizing new areas and maintaining their dominance in wetland ecosystems.

Water, though less universal, is a critical disperser in aquatic and riparian environments. Moss spores, often hydrophobic, float on water surfaces, allowing them to reach new substrates downstream. This method is especially vital for species like *Fontinalis antipyretica*, which grows submerged in freshwater streams. The spores’ buoyancy and water’s flow combine to ensure colonization of suitable habitats, even in areas inaccessible by wind. However, this method is limited to mosses in or near water bodies, highlighting the niche-specific nature of this dispersal strategy.

Animals, including insects and larger fauna, contribute to spore dispersal through indirect means. As creatures traverse moss-covered surfaces, spores adhere to their bodies, later deposited elsewhere. For example, slugs and snails, common in damp woodland habitats, inadvertently carry spores on their mucus trails. Similarly, birds and mammals may transport spores in their feathers or fur, facilitating long-distance dispersal. This method, while less predictable than wind or water, adds a layer of ecological interconnectedness, demonstrating how mosses leverage existing animal movements for survival.

Each dispersal method has its advantages and limitations, shaping the distribution and diversity of moss species. Wind maximizes reach but lacks specificity, while water ensures targeted delivery in aquatic systems. Animal-mediated dispersal, though sporadic, bridges gaps between isolated habitats. Understanding these mechanisms not only sheds light on moss ecology but also informs conservation efforts, particularly in fragmented landscapes where natural dispersal pathways may be disrupted. By mimicking these processes—such as introducing spore-laden substrates near water sources—humans can aid in restoring moss populations in degraded ecosystems.

Practical applications of this knowledge extend to horticulture and habitat restoration. For instance, gardeners cultivating mosses can enhance spore dispersal by placing sporangium-bearing plants in windy or water-adjacent locations. In restoration projects, strategically introducing animal pathways, like log piles or brush piles, can facilitate spore movement. These methods, grounded in the natural dispersal strategies of mosses, ensure the successful establishment of these resilient plants in diverse settings. Ultimately, the interplay of wind, water, and animals in spore dispersal underscores the intricate balance between mosses and their environment, a relationship honed over millions of years of evolution.

Discovering Timmask Spores: A Comprehensive Guide to Sourcing and Harvesting

You may want to see also

Sporangium vs. Gametangia: Sporangium produces spores, while gametangia produce gametes in moss life cycles

Mosses, like all plants, have a life cycle that alternates between a gametophyte (n) and a sporophyte (2n) generation. Central to understanding this cycle is distinguishing between sporangia and gametangia, structures that often confuse beginners in botany. Sporangia are the spore-producing organs found on the sporophyte, the diploid phase of the moss. These structures release spores that develop into the gametophyte, the haploid phase. In contrast, gametangia—specifically antheridia (male) and archegonia (female)—are found on the gametophyte and produce gametes (sperm and eggs) for sexual reproduction. This fundamental difference in function is key to grasping moss reproduction.

Consider the lifecycle stages to clarify their roles. After a moss spore germinates, it grows into a gametophyte, which is typically the dominant, long-lasting phase in mosses. On this gametophyte, antheridia and archegonia develop. Sperm from the antheridia swim to the archegonia to fertilize the egg, resulting in a zygote that grows into the sporophyte. The sporophyte, often seen as a small stalk with a capsule-like structure, then produces sporangia. Within these sporangia, spores are formed through meiosis, completing the cycle. This alternation highlights the distinct roles: sporangia drive the transition from sporophyte to gametophyte, while gametangia facilitate the reverse.

A practical tip for identifying these structures in the field is to examine mature moss plants under a hand lens. The sporophyte, with its sporangium, is usually visible as a capsule atop a slender seta (stalk). Gametangia, however, are microscopic and require closer inspection of the gametophyte. Look for small, swollen structures (archegonia) or clusters of cells (antheridia) on the gametophyte’s surface, often near the base or on specialized branches. Understanding these differences not only aids in identification but also deepens appreciation for the intricate reproductive strategies of mosses.

From an evolutionary perspective, the separation of spore and gamete production into distinct structures reflects adaptation to terrestrial environments. Sporangia protect developing spores from desiccation, ensuring successful dispersal. Gametangia, meanwhile, are optimized for localized fertilization, reducing reliance on water for sperm motility. This division of labor underscores the efficiency of moss life cycles, which have remained largely unchanged for millions of years. By studying sporangia and gametangia, we gain insight into the resilience and diversity of these ancient plants.

In educational settings, teaching the distinction between sporangia and gametangia can be enhanced through hands-on activities. For instance, students can dissect moss sporophytes to observe sporangia under a microscope, noting their spore-filled interiors. Contrasting this with the gametophyte’s gametangia, visible as tiny bumps or clusters, reinforces their unique functions. Such activities not only clarify concepts but also foster curiosity about plant biology. Whether for research, education, or personal interest, understanding sporangia and gametangia is essential for unraveling the fascinating world of moss reproduction.

Can Dehydrated Morel Spores Still Grow Mushrooms? Viability Explored

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A sporangium is a structure in plants, fungi, and some other organisms that produces and contains spores.

Yes, moss spores are produced within a sporangium, which is located at the tip of the seta (stalk) in the sporophyte generation of the moss life cycle.

Moss spores develop through meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, inside the sporangium. Once mature, the spores are released through an opening called the stoma.

Moss spores are typically found inside the sporangium until they are released into the environment. Once released, they disperse and can germinate under suitable conditions to form a new moss plant.

After releasing the spores, the sporangium usually withers and deteriorates, as its primary function is to produce and disperse spores. The moss plant then relies on the gametophyte generation to continue its life cycle.