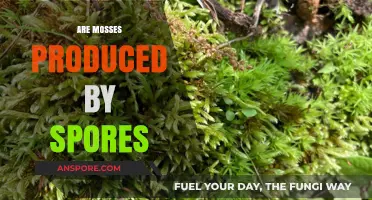

Mosses are a diverse group of non-vascular plants that belong to the division Bryophyta, and they are indeed spore-bearing organisms. Unlike vascular plants that produce seeds, mosses reproduce through spores, which are haploid, single-celled structures dispersed into the environment. These spores develop into gametophytes, the dominant phase in the moss life cycle, which are the green, leafy structures commonly seen in moist environments. The gametophytes produce reproductive organs—male antheridia and female archegonia—where sperm and eggs are formed, respectively. After fertilization, a diploid sporophyte grows, typically as a small stalk with a capsule at the tip, where spores are produced via meiosis. This alternation of generations between gametophyte and sporophyte stages is a defining characteristic of mosses and other bryophytes, highlighting their unique and ancient reproductive strategy.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproduction | Mosses are spore-bearing plants, reproducing via spores rather than seeds. |

| Life Cycle | Exhibit an alternation of generations (sporophyte and gametophyte phases), typical of spore-bearing plants. |

| Sporophyte Structure | Produce spores in a capsule (sporangium) atop a stalk, which grows from the gametophyte. |

| Gametophyte Dominance | The gametophyte stage is the dominant, long-lived, and independent phase in mosses. |

| Spore Dispersal | Spores are dispersed by wind, water, or animals to colonize new areas. |

| Classification | Belong to the division Bryophyta, which includes non-vascular, spore-bearing plants. |

| Lack of Seeds | Do not produce flowers, fruits, or seeds, distinguishing them from seed-bearing plants. |

| Habitat | Thrive in moist, shady environments where spores can germinate successfully. |

| Ecological Role | Play a key role in ecosystems as pioneers in soil formation and moisture retention. |

| Evolutionary Significance | Considered early land plants, providing insights into the evolution of spore-bearing organisms. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Moss Life Cycle: Alternation of generations, sporophyte dependent on gametophyte, spores develop in capsules

- Spore Dispersal: Wind-dispersed spores, lightweight and numerous, ensure wide colonization

- Capsule Structure: Sporophyte capsule releases spores through peristome teeth mechanism

- Gametophyte Dominance: Gametophyte is the dominant, long-lived, photosynthetic stage in mosses

- Sporophyte Dependence: Sporophyte relies on gametophyte for nutrients and water supply

Moss Life Cycle: Alternation of generations, sporophyte dependent on gametophyte, spores develop in capsules

Mosses are indeed spore-bearing plants, and their life cycle is a fascinating example of alternation of generations, a reproductive strategy shared by many plants but particularly pronounced in mosses. This cycle involves two distinct phases: the gametophyte and the sporophyte. The gametophyte, which is the dominant and more visible stage, is a haploid organism that produces gametes (sex cells). In mosses, this is the green, carpet-like structure we typically see covering rocks or soil. The sporophyte, on the other hand, is a diploid organism that develops from the fertilized egg and produces spores. Unlike vascular plants, the moss sporophyte remains physically attached to and dependent on the gametophyte for nutrients and water throughout its life.

The dependency of the sporophyte on the gametophyte is a defining feature of mosses. The sporophyte grows as a slender stalk with a capsule at its tip, emerging directly from the gametophyte. This capsule is where spores develop through meiosis, a process that reduces the chromosome number, preparing the spores for dispersal. The capsule is not just a passive container; it is a highly specialized structure with a lid (operculum) that eventually falls off, and a ring of teeth (peristome) that helps regulate spore release. This intricate design ensures that spores are dispersed efficiently, often with the aid of wind or water.

To understand the practical implications of this life cycle, consider the following steps for observing spore development in mosses. First, locate a mature moss plant with visible sporophytes. These appear as small, stalked structures rising from the gametophyte. Using a magnifying glass or microscope, examine the capsule at the top of the sporophyte. If the capsule is mature, you may observe the operculum beginning to separate or the peristome teeth opening. Gently tapping the capsule can release spores, which are typically microscopic and may require a microscope to see clearly. This hands-on approach not only illustrates the alternation of generations but also highlights the sporophyte’s reliance on the gametophyte for support and resources.

Comparatively, the life cycle of mosses contrasts sharply with that of vascular plants like ferns or flowering plants. In vascular plants, the sporophyte is the dominant generation, and the gametophyte is often reduced to a tiny, short-lived stage. Mosses, however, retain a gametophyte-centric life cycle, a trait believed to be ancestral among land plants. This difference underscores the evolutionary significance of mosses and their role in understanding plant evolution. By studying mosses, scientists gain insights into how early land plants may have reproduced and adapted to terrestrial environments.

In conclusion, the moss life cycle is a remarkable demonstration of alternation of generations, with the sporophyte entirely dependent on the gametophyte and spores developing in specialized capsules. This unique relationship not only ensures the survival and dispersal of mosses but also provides a window into the evolutionary history of plants. Whether observed in the wild or under a microscope, the moss life cycle offers both scientific value and a deeper appreciation for the complexity of these seemingly simple organisms.

Understanding Dangerous Mold Spore Levels: Health Risks and Safety Thresholds

You may want to see also

Spore Dispersal: Wind-dispersed spores, lightweight and numerous, ensure wide colonization

Mosses, as spore-bearing plants, have mastered the art of dispersal through the production of lightweight, wind-carried spores. These spores, often measuring just a few micrometers in diameter, are designed for efficiency. Their minuscule size and dry, resilient structure allow them to travel vast distances on even the gentlest breeze. This adaptation ensures that mosses can colonize diverse habitats, from damp forest floors to rocky outcrops, without relying on external vectors like animals or water.

Consider the mechanics of wind dispersal: when a moss sporophyte matures, it releases spores from its capsule in staggering quantities—sometimes millions per plant. This sheer volume increases the likelihood that at least some spores will land in suitable environments. The process is passive yet highly effective, as wind currents can carry spores across kilometers, even over geographical barriers like rivers or hills. For gardeners or ecologists aiming to propagate moss, mimicking this natural dispersal by scattering dried moss fragments in windy conditions can yield successful colonization.

A comparative analysis highlights the advantage of wind dispersal over other methods. Unlike seeds, which often require specific conditions or carriers, spores are self-sufficient. Their lightweight nature and aerodynamic shape make them ideal for wind transport, while their hard outer walls protect them from desiccation and predation during transit. This contrasts with water-dispersed spores, which are limited by proximity to water bodies, or animal-dispersed seeds, which rely on unpredictable interactions with fauna. Wind dispersal, therefore, maximizes both range and adaptability.

Practical applications of this knowledge abound. For instance, in moss gardening, positioning moss patches in open, breezy areas can encourage natural spread. Similarly, conservation efforts in degraded ecosystems can leverage wind dispersal by introducing moss spores in strategic locations to facilitate rapid colonization. However, caution is necessary: while wind ensures wide distribution, it also risks depositing spores in inhospitable areas. Pairing dispersal with habitat assessment—such as ensuring adequate moisture and shade—optimizes success rates.

Ultimately, the wind-dispersed spores of mosses exemplify nature’s ingenuity in solving the challenge of colonization. Their lightweight, numerous, and resilient design ensures that mosses thrive in environments where other plants might struggle. By understanding and harnessing this mechanism, we can not only appreciate the biology of mosses but also apply their strategies to restore, propagate, and conserve these vital organisms in diverse ecosystems.

Are Spores on Potatoes Safe to Eat? A Complete Guide

You may want to see also

Capsule Structure: Sporophyte capsule releases spores through peristome teeth mechanism

Mosses, as spore-bearing plants, rely on a sophisticated mechanism to disperse their spores: the sporophyte capsule and its peristome teeth. This structure is a marvel of evolutionary adaptation, ensuring efficient spore release under varying environmental conditions. The capsule, typically positioned atop a slender seta, houses the spores and is capped by a lid-like operculum. As the capsule matures, it dries, creating tension that eventually forces the operculum to detach. This exposes the peristome, a ring of specialized teeth that regulate spore release.

The peristome teeth are not merely static structures but dynamic, hygroscopic elements that respond to changes in humidity. When the air is dry, the teeth curl inward, closing the capsule to prevent premature spore release. In humid conditions, they unfurl, widening the capsule opening and allowing spores to escape gradually. This mechanism ensures that spores are dispersed during optimal conditions, increasing their chances of germination. For instance, in *Funaria hygrometrica*, the peristome teeth exhibit a pronounced hygroscopic response, making it a prime example of this adaptation.

To observe this mechanism in action, collect a mature moss sporophyte capsule and place it under a stereoscope. Gradually increase the humidity around the capsule using a spray bottle or damp paper towel. Note how the peristome teeth respond, transitioning from a closed to an open state. This simple experiment highlights the functional elegance of the peristome and its role in spore dispersal. For educators, this activity can be a practical way to teach students about plant adaptations and life cycles.

While the peristome teeth mechanism is highly effective, it is not without limitations. In extremely dry environments, the teeth may remain closed for extended periods, delaying spore release. Conversely, in overly wet conditions, spores may clump together, reducing dispersal efficiency. Understanding these constraints is crucial for conservation efforts, particularly in habitats where mosses play a key role in ecosystem stability. For instance, in peatlands, where mosses like *Sphagnum* dominate, disruptions to spore dispersal could have cascading ecological effects.

In conclusion, the sporophyte capsule and peristome teeth represent a finely tuned system for spore release in mosses. By balancing environmental responsiveness with structural precision, this mechanism ensures the survival and propagation of moss species across diverse habitats. Whether for scientific study, educational purposes, or conservation efforts, understanding this structure provides valuable insights into the biology of spore-bearing plants. Practical observations and experiments can further illuminate its function, making it a compelling subject for exploration.

Understanding Spore-Forming Bacteria: Survival Mechanisms and Health Implications

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Gametophyte Dominance: Gametophyte is the dominant, long-lived, photosynthetic stage in mosses

Mosses, unlike most plants, exhibit a unique life cycle where the gametophyte stage takes center stage. This green, leafy structure that we commonly recognize as moss is not just a fleeting part of its life cycle but the dominant, long-lived phase. In contrast to vascular plants, where the sporophyte is the more prominent and enduring stage, mosses invert this hierarchy. The gametophyte in mosses is not only persistent but also fully photosynthetic, enabling it to sustain itself independently. This characteristic is crucial for understanding why mosses thrive in diverse environments, from damp forests to rocky outcrops, without relying on extensive root systems.

To appreciate gametophyte dominance, consider the moss life cycle. It begins with a spore germinating into a protonema, a thread-like structure that eventually develops into the gametophyte. This gametophyte produces gametes (sperm and eggs) through specialized structures, leading to fertilization and the formation of a sporophyte. However, the sporophyte remains dependent on the gametophyte for nutrients and water, highlighting the latter’s central role. For instance, the sporophyte of a moss like *Sphagnum* grows directly from the gametophyte and relies on it for survival, even as it produces spores for the next generation.

From a practical standpoint, understanding gametophyte dominance is essential for cultivating mosses in gardens or for conservation efforts. Mosses prefer shaded, moist environments where their gametophytes can thrive without competition from larger plants. To grow moss intentionally, ensure the substrate is consistently damp but not waterlogged, and avoid direct sunlight, which can desiccate the delicate gametophyte tissues. For example, mixing moss fragments with buttermilk or yogurt and spreading the mixture on soil or stone can encourage gametophyte establishment, as the acidity and nutrients in these substances promote growth.

Comparatively, the dominance of the gametophyte in mosses contrasts sharply with ferns and seed plants, where the sporophyte is the independent, long-lived stage. This difference underscores the evolutionary divergence of bryophytes (mosses and their relatives) from other plant groups. While ferns and seed plants developed vascular tissues to support larger sporophytes, mosses retained a simpler structure, with the gametophyte remaining the primary photosynthetic and reproductive unit. This evolutionary choice allows mosses to colonize niches inaccessible to more complex plants, such as bare rock or tree bark.

In conclusion, gametophyte dominance in mosses is a fascinating adaptation that defines their ecology and life cycle. By focusing on this stage, mosses have evolved to thrive in environments where other plants struggle. Whether you’re a gardener, botanist, or simply an enthusiast, recognizing the significance of the gametophyte offers valuable insights into moss cultivation and conservation. Its persistence, photosynthetic capability, and central role in reproduction make it a cornerstone of moss biology, illustrating the diversity of plant life cycles in the natural world.

Mastering Mushroom Cultivation: A Step-by-Step Guide to Using Spore Syringes

You may want to see also

Sporophyte Dependence: Sporophyte relies on gametophyte for nutrients and water supply

Mosses, as spore-bearing plants, exhibit a unique life cycle where the sporophyte generation is fundamentally dependent on the gametophyte for survival. Unlike vascular plants, where the sporophyte is the dominant and independent phase, moss sporophytes lack true roots, stems, and leaves. This anatomical simplicity means they cannot absorb water or nutrients directly from the environment. Instead, they rely entirely on the gametophyte—the moss’s leafy, photosynthetic structure—for these essential resources. This interdependence is a defining feature of bryophytes and highlights the gametophyte’s central role in their life cycle.

Consider the practical implications of this dependence for moss cultivation. If you’re growing moss in a terrarium or garden, ensuring the health of the gametophyte is critical. The gametophyte not only anchors the sporophyte but also supplies it with water and nutrients via specialized structures called the foot and seta. To support this process, maintain consistent moisture levels; mosses thrive in humid environments where water can be readily absorbed by the gametophyte. Avoid overwatering, as this can lead to rot, but ensure the substrate remains damp to facilitate nutrient transfer to the sporophyte.

From an evolutionary perspective, this dependence sheds light on why mosses are often confined to moist, shaded habitats. Without the ability to independently access resources, sporophytes are vulnerable in dry or nutrient-poor environments. This limitation has shaped their distribution and underscores the gametophyte’s role as the primary photosynthetic and absorptive organ. In contrast, vascular plants’ sporophytes have evolved independence, allowing them to colonize diverse ecosystems. Mosses, however, remain tied to their gametophytes, a trait that both constrains and defines their ecological niche.

For educators or enthusiasts studying mosses, observing this relationship firsthand can be enlightening. Collect a moss sample with sporophytes and examine it under a magnifying glass or microscope. Notice how the sporophyte is physically attached to and supported by the gametophyte. Experiment with varying moisture levels to observe how the gametophyte’s health directly impacts the sporophyte’s viability. This hands-on approach not only reinforces the concept of sporophyte dependence but also fosters a deeper appreciation for the intricate biology of these ancient plants.

Basidiomycete Pathogens Without Spores: Monocyclic or Not?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, mosses are spore-bearing plants. They belong to the group of non-vascular plants called bryophytes and reproduce via spores rather than seeds.

Mosses produce spores in structures called sporangia, located at the tips of their gametophytes (the leafy, green part). Spores are dispersed by wind or water once the sporangium matures and dries out.

No, mosses do not produce seeds. They are primitive plants that rely on spores for reproduction, unlike more advanced plants like flowering plants or gymnosperms, which produce seeds.