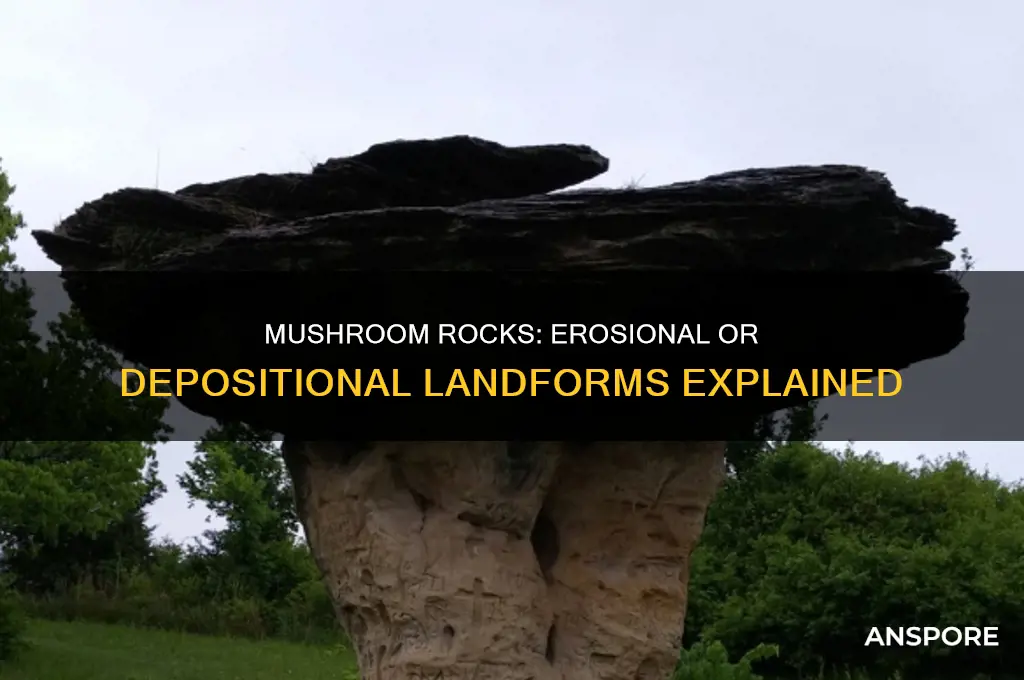

Mushroom rocks, characterized by their distinctive cap-like shapes, are fascinating geological formations that raise questions about their origin. The debate centers on whether these structures are primarily the result of erosional or depositional processes. Erosion, driven by wind, water, or ice, can selectively wear away softer materials, leaving behind harder, more resistant rock to form the cap. Conversely, depositional processes, such as the accumulation of sediments or minerals, could theoretically create similar shapes under specific conditions. Understanding the dominant process behind mushroom rocks not only sheds light on their formation but also provides insights into the broader geological history of their environments.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Formation Process | Erosional |

| Shape | Mushroom-like, with a wider top and narrower base |

| Primary Cause | Differential erosion, where softer rock is eroded faster than harder rock |

| Rock Type | Typically formed in sandstone, limestone, or other layered sedimentary rocks |

| Erosion Mechanism | Wind, water, or ice erosion that preferentially removes softer material |

| Cap Formation | Harder, more resistant rock forms the cap, protecting the softer rock beneath |

| Stem Formation | Softer rock beneath the cap is eroded more slowly, creating a narrower stem |

| Common Locations | Arid or semi-arid regions with exposed rock formations |

| Examples | Pedra do Camelo in Brazil, Mushroom Rocks State Park in Kansas, USA |

| Significance | Provides insights into erosion patterns, rock layering, and geological history |

| Preservation | Often protected as natural landmarks or geological features due to their unique shape |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Erosional Processes Shaping Mushroom Rocks

Mushroom rocks, characterized by their distinctive cap-like shapes atop narrower stems, are primarily the result of erosional processes rather than depositional ones. These unique geological formations are shaped by the differential erosion of rocks with varying resistance to weathering. The process begins with the presence of a harder, more resistant rock layer capping a softer, less resistant layer beneath. Over time, wind, water, and other erosional agents wear away the softer material more rapidly, leaving behind the harder cap that creates the mushroom-like appearance. This phenomenon is a clear example of how erosion can sculpt landscapes into fascinating forms.

One of the key erosional processes involved in shaping mushroom rocks is physical weathering, particularly through the action of wind and sand abrasion. In arid or semi-arid environments, wind-driven sand particles act like natural sandpaper, gradually wearing away the softer rock. The softer rock at the base erodes more quickly, while the harder cap remains relatively intact, forming the stem and cap structure. This process is particularly evident in desert regions, where wind erosion is a dominant force. The constant bombardment by sand grains creates a smooth, rounded shape, further enhancing the mushroom-like appearance.

Another critical erosional process is chemical weathering, which often works in tandem with physical weathering. Chemical reactions, such as oxidation or dissolution, break down the softer rock more rapidly than the harder cap. For instance, if the softer rock contains minerals that are more susceptible to chemical breakdown, it will erode faster, leaving the more resistant cap behind. Water, especially in areas with seasonal rainfall, can accelerate this process by carrying acids or dissolved minerals that enhance chemical weathering. Over time, this differential erosion carves out the characteristic mushroom shape.

Water erosion also plays a significant role in shaping mushroom rocks, particularly in areas with flowing water or periodic flooding. Streams or rivers can carry sediment that abrades the softer rock, while the harder cap remains largely unaffected. Additionally, the undercutting effect of water can weaken the base of the rock, causing it to narrow and form a distinct stem. This process is often observed in riverbeds or areas with intermittent water flow, where the combination of abrasion and undercutting creates the mushroom-like morphology.

Finally, biological activity can contribute to the erosional processes shaping mushroom rocks, though it is less dominant than physical and chemical weathering. Plant roots, burrowing animals, or microbial activity can weaken the softer rock, making it more susceptible to erosion. As the softer material is gradually removed, the harder cap remains, further accentuating the mushroom shape. While biological factors are secondary, they can still play a role in the overall erosional process, particularly in environments where biological activity is high.

In summary, mushroom rocks are primarily shaped by erosional processes that exploit the differential resistance of rock layers. Physical weathering, chemical weathering, water erosion, and biological activity all contribute to the gradual formation of these unique structures. Understanding these processes not only highlights the dynamic nature of Earth’s landscapes but also underscores the importance of erosion in sculpting geological wonders like mushroom rocks.

Quickly Rehydrating Mushrooms: A Simple Guide

You may want to see also

Depositional Factors in Mushroom Rock Formation

Mushroom rocks, characterized by their distinctive cap-like shapes, are primarily the result of depositional processes rather than purely erosional ones. While erosion plays a role in shaping these formations, the initial creation of the rock structures is fundamentally tied to depositional factors. These factors involve the accumulation and lithification of sediments under specific environmental conditions, setting the stage for the subsequent erosional processes that refine the mushroom-like morphology.

One key depositional factor in mushroom rock formation is the type and layering of sediments. Mushroom rocks often form in areas where fine-grained sediments, such as silt, clay, or fine sand, are deposited in layers. These layers may alternate with more resistant materials like coarser sand, gravel, or cemented sediments. The differential resistance of these layers to erosion is crucial. The harder, more resistant material forms the "cap" of the mushroom, while the softer material beneath is gradually eroded, creating the characteristic stem. This layering is typically the result of deposition in environments like river deltas, lake beds, or shallow marine settings, where sediment types vary over time due to changes in water flow, sediment supply, or environmental conditions.

Another important depositional factor is the process of lithification, which consolidates loose sediments into solid rock. Lithification occurs through compaction and cementation, often facilitated by minerals dissolved in groundwater. In mushroom rock formations, the cap material is usually more cemented or compacted than the stem material, making it more resistant to erosion. This differential lithification can be influenced by variations in sediment composition, pore water chemistry, or the presence of organic matter. For example, calcium carbonate or silica cementation may strengthen certain layers, enhancing their durability against erosive forces.

The depositional environment also plays a critical role in mushroom rock formation. These structures are commonly found in arid or semi-arid regions where erosion rates are relatively high, but the initial deposition occurred in wetter conditions. Ancient riverbeds, floodplains, or coastal areas are typical settings where layered sediments accumulate. Over time, as the climate changes or the landscape evolves, these areas may become exposed to wind and water erosion, which preferentially removes the softer materials, leaving behind the harder, mushroom-shaped remnants.

Finally, the spatial distribution of sediments during deposition influences the eventual formation of mushroom rocks. Sediment deposition is often uneven, with thicker accumulations in certain areas due to factors like topography, water flow patterns, or sediment transport mechanisms. These thicker sections are more likely to develop into the caps of mushroom rocks, as they provide a greater volume of resistant material. The surrounding areas, where sediment deposition was thinner or composed of less resistant material, are more susceptible to erosion, contributing to the isolation and shaping of the mushroom structures.

In summary, depositional factors are foundational to mushroom rock formation, involving the layering of sediments, lithification processes, the nature of the depositional environment, and the spatial distribution of materials. These factors create the initial conditions necessary for the subsequent erosional processes that sculpt the iconic mushroom shapes. Understanding these depositional mechanisms provides critical insights into the geological history and environmental conditions that give rise to these unique landforms.

Select Mushrooms: Freshness and Quality Guide

You may want to see also

Role of Wind and Water in Erosion

Wind and water are two of the most powerful agents of erosion, shaping landscapes over time through their relentless forces. Erosion is the process by which natural elements wear away rocks and soil, and both wind and water play distinct yet complementary roles in this geological phenomenon. Mushroom rocks, also known as pedestal rocks or hoodoos, are fascinating landforms that result from differential erosion, where harder rock layers protect softer layers beneath, creating a mushroom-like shape. Understanding the role of wind and water in erosion is crucial to comprehending how these unique structures form and persist.

Water Erosion: The Sculptor of Landscapes

Water is a primary erosional force, acting through processes such as rainfall, rivers, waves, and glaciers. In the context of mushroom rocks, water erosion often begins with the dissolution or weakening of softer rock layers. Rainwater, especially when slightly acidic, can chemically weather rocks by breaking down minerals. As water flows over the surface, it carries sediment, gradually wearing away the softer materials. This process leaves behind harder, more resistant rock layers, which act as protective caps over the softer rock below. Over time, the softer rock is eroded, creating the characteristic stem of the mushroom rock. Water’s ability to transport sediment also contributes to the smoothing and shaping of these structures, as finer particles are removed, leaving behind the more durable forms.

Wind Erosion: The Carver of Delicate Features

Wind erosion, while less dominant than water erosion in many environments, plays a significant role in arid and semi-arid regions where mushroom rocks often form. Wind carries sand and dust particles, which act like natural sandpaper, abrading exposed rock surfaces. This process, known as deflation, removes loose particles and gradually wears down softer rock. Wind erosion is particularly effective in shaping the finer details of mushroom rocks, such as their smooth, rounded edges and undercut bases. In areas where water erosion initiates the formation of these structures, wind erosion often refines them, enhancing their distinctive shapes. The combination of wind and water erosion ensures that the harder cap rock remains intact while the softer layers are progressively removed.

The Synergy of Wind and Water

The formation of mushroom rocks is rarely the result of a single erosional agent; instead, it is the synergy of wind and water that creates these remarkable landforms. Water often initiates the process by weakening and removing softer materials, while wind accelerates the erosion of exposed surfaces, particularly in dry climates. This interplay highlights the dynamic nature of erosional processes and how different agents can work together to shape the Earth’s surface. For example, in regions with seasonal rainfall, water erosion may dominate during wet periods, while wind erosion takes over in dry seasons, creating a cyclical process that gradually carves out mushroom rocks.

Preservation and Vulnerability

While wind and water are responsible for the creation of mushroom rocks, they also pose a threat to their long-term preservation. Continued erosion can eventually wear away even the hardest cap rocks, leading to the collapse of these structures. Additionally, human activities, such as tourism and land development, can accelerate erosion by disturbing the delicate balance of these natural processes. Understanding the role of wind and water in erosion is not only essential for explaining the formation of mushroom rocks but also for implementing conservation efforts to protect these unique geological features for future generations.

In conclusion, mushroom rocks are undeniably erosional features, shaped by the combined forces of wind and water. These agents work in tandem to remove softer materials, leaving behind the distinctive mushroom-like structures. By studying their role in erosion, we gain valuable insights into the processes that sculpt our planet’s landscapes and the importance of preserving these natural wonders.

Mushroom Bhaji: Spicy, Savory, and Delicious

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Sediment Accumulation and Deposition Mechanisms

Mushroom rocks, characterized by their distinctive cap-like shapes, are primarily formed through erosional processes rather than depositional ones. However, understanding the broader context of sediment accumulation and deposition mechanisms is crucial to appreciating how such unique landforms come into existence. Sediment accumulation and deposition are fundamental geological processes that involve the settling and layering of particles transported by wind, water, ice, or gravity. These processes occur in various environments, including rivers, lakes, oceans, and deserts, and are influenced by factors such as particle size, transport medium, and environmental conditions.

In the case of mushroom rocks, the formation begins with the differential erosion of rock layers. Softer materials are worn away more quickly, leaving behind harder, more resistant rocks that eventually take on the mushroom-like shape. While erosion is the dominant process here, deposition plays a secondary role in the broader landscape. For instance, sediments eroded from surrounding areas may accumulate at the base of mushroom rocks, contributing to the stability of the structure or forming a protective layer that influences further erosion patterns. This interplay between erosion and deposition highlights the complexity of geological processes.

Sediment deposition typically occurs when the transporting medium (e.g., water or wind) loses energy, causing particles to settle out. In fluvial environments, such as rivers, sediments accumulate in areas where flow velocity decreases, such as behind obstacles or in wider sections of the channel. Similarly, in aeolian environments, wind-borne sediments are deposited when wind speed diminishes, often forming dunes or loess deposits. These depositional processes can create layers of sediment that, over time, may lithify into sedimentary rocks, which can later be subjected to erosional forces.

The mechanisms of sediment accumulation are closely tied to the characteristics of the sediment particles themselves. Finer particles, such as silt and clay, tend to travel farther and settle in quieter environments, while coarser particles like sand and gravel are deposited closer to their source. This sorting of sediments by size and weight is a key aspect of depositional systems. In the context of mushroom rocks, the sediments accumulating at their base are often a mix of locally derived materials and particles transported from upstream or upwind, reflecting the dynamic nature of sediment transport and deposition.

Understanding sediment accumulation and deposition mechanisms is essential for interpreting the geological history of an area. For example, the presence of well-sorted, layered sediments suggests a stable depositional environment, whereas poorly sorted sediments may indicate high-energy conditions or rapid deposition. In the case of mushroom rocks, the surrounding sedimentary layers can provide clues about past environmental conditions, such as ancient river systems or wind patterns, that influenced both deposition and subsequent erosion.

In summary, while mushroom rocks are primarily erosional features, their formation and preservation are influenced by sediment accumulation and deposition mechanisms operating in the broader landscape. These processes, driven by the transport and settling of sediments, shape the Earth's surface and create the diverse geological features we observe today. By studying these mechanisms, geologists can gain insights into the complex interactions between erosion and deposition that have sculpted our planet over millions of years.

Mushrooms: Superfood or Medicine?

You may want to see also

Differentiating Erosional vs. Depositional Features

Mushroom rocks, also known as pedestal rocks or rock mushrooms, are fascinating geological formations that often spark curiosity about their origin—whether they are the result of erosional or depositional processes. To differentiate between erosional and depositional features, it's essential to understand the mechanisms behind each process. Erosional features are formed by the removal of material through agents like wind, water, or ice, while depositional features result from the accumulation of sediment or other materials. Mushroom rocks primarily exhibit erosional characteristics, as they are shaped by the differential erosion of harder and softer rock layers.

Erosional features like mushroom rocks typically develop in environments where resistant caprocks protect the underlying softer material. The caprock, often composed of harder materials such as sandstone or limestone, erodes more slowly than the softer base, creating a distinctive mushroom-like shape. This process is driven by physical weathering, where wind, water, or temperature changes gradually wear away the exposed surfaces. In contrast, depositional features, such as dunes or alluvial fans, are formed by the accumulation of sediments transported by wind, water, or ice and deposited in new locations. Mushroom rocks lack the layered or stratified appearance commonly associated with depositional processes.

Another key distinction lies in the spatial distribution and orientation of these features. Erosional formations like mushroom rocks are often found in arid or semi-arid regions where wind and sparse rainfall dominate the landscape. The isolated nature of these rocks highlights the localized removal of material rather than the addition of new sediments. Depositional features, on the other hand, are usually part of larger systems, such as river deltas or sand dunes, where sediments are actively being transported and deposited over broader areas.

To further differentiate, examine the texture and composition of the rocks. Erosional features often display smooth, rounded surfaces due to prolonged abrasion, while depositional features may show distinct layers or sorting of sediments. Mushroom rocks, with their weathered caps and eroded stems, clearly indicate prolonged exposure to erosive forces rather than the accumulation of new material.

In summary, mushroom rocks are primarily erosional features shaped by differential weathering and the protective effect of harder caprocks. By contrasting the processes of material removal (erosion) and material accumulation (deposition), one can confidently classify these formations. Understanding these distinctions not only clarifies the origin of mushroom rocks but also enhances the broader study of geological landscapes and their evolutionary processes.

Burger King's Mushroom Burger: Does it Exist?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mushroom rocks are primarily formed through erosional processes. The distinctive mushroom shape is created by differential erosion, where harder rock layers resist erosion more than softer layers, resulting in a cap-like structure.

Deposition plays a minimal role in the formation of mushroom rocks. While sediments may accumulate around the base, the mushroom shape itself is primarily the result of erosion, not deposition.

Mushroom rocks are predominantly erosional features, but depositional processes can contribute to their surroundings. For example, sediment deposition may occur at the base, but the mushroom shape is still primarily due to erosion.