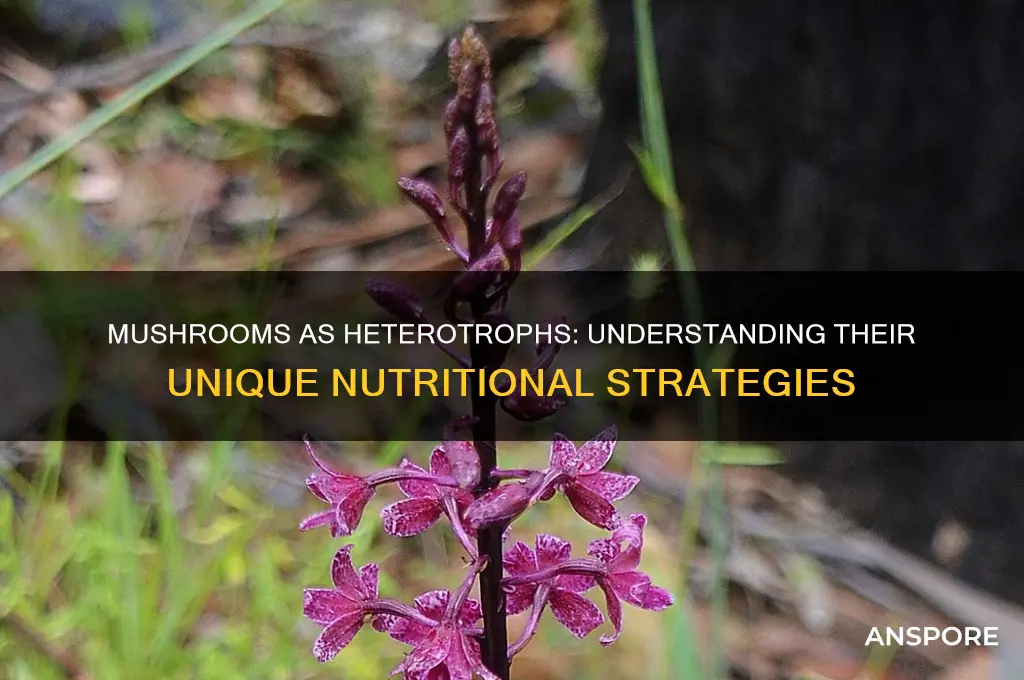

Mushrooms, often mistaken for plants, are actually fungi and serve as a prime example of heterotrophs, organisms that cannot produce their own food and must obtain nutrients from external sources. Unlike plants, which use photosynthesis to convert sunlight into energy, mushrooms lack chlorophyll and instead rely on absorbing organic matter from their environment, typically through the decomposition of dead plant and animal material. This process, known as saprotrophy, highlights their heterotrophic nature, as they break down complex organic compounds into simpler forms to meet their nutritional needs. Understanding mushrooms as heterotrophs not only clarifies their ecological role as decomposers but also underscores their distinct classification within the biological kingdom Fungi.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition of Heterotrophs | Organisms that cannot produce their own food and rely on other organisms for nutrition. |

| Mushroom Classification | Fungi (Kingdom Fungi). |

| Nutritional Mode | Heterotrophic; mushrooms obtain nutrients by decomposing organic matter (saprotrophic) or forming symbiotic relationships (mycorrhizal or parasitic). |

| Photosynthesis Ability | Absent; mushrooms lack chlorophyll and cannot perform photosynthesis. |

| Energy Source | Organic compounds from dead or living organisms. |

| Cell Wall Composition | Chitin, not cellulose (unlike plants). |

| Examples of Heterotrophic Fungi | All mushrooms, yeasts, and molds. |

| Role in Ecosystem | Decomposers, breaking down complex organic materials into simpler substances. |

| Contrast with Autotrophs | Unlike plants (autotrophs), mushrooms do not produce their own food via photosynthesis. |

| Scientific Consensus | Universally accepted that mushrooms are heterotrophs. |

Explore related products

$7.62 $14.95

What You'll Learn

- Mushroom Nutrition Sources: Mushrooms absorb organic matter, not photosynthesis, fitting heterotroph definition

- Saprotrophic Nature: They decompose dead organisms, a key heterotrophic trait

- Mycorrhizal Relationships: Symbiotic with plants, still rely on external carbon sources

- Lack of Chlorophyll: No chlorophyll means no photosynthesis, confirming heterotrophy

- Energy Acquisition: Mushrooms obtain energy from pre-formed organic compounds, not sunlight

Mushroom Nutrition Sources: Mushrooms absorb organic matter, not photosynthesis, fitting heterotroph definition

Mushrooms are a fascinating example of heterotrophs, organisms that cannot produce their own food through photosynthesis and instead rely on external sources of organic matter for nutrition. Unlike plants, which use sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide to synthesize nutrients, mushrooms lack chlorophyll and the necessary cellular machinery for photosynthesis. This fundamental difference in energy acquisition places mushrooms firmly in the heterotrophic category. Their nutritional strategy involves absorbing organic compounds from their environment, a process that underscores their dependence on pre-existing organic matter.

The primary method by which mushrooms obtain nutrients is through absorption. They secrete enzymes into their surroundings, breaking down complex organic materials such as dead plant and animal matter, wood, or even soil particles. These enzymes decompose the organic substrates into simpler compounds, which the mushrooms then absorb directly through their hyphae, the thread-like structures that make up their body (mycelium). This absorptive mechanism is highly efficient and allows mushrooms to thrive in diverse ecosystems, from forest floors to decaying logs. The inability to photosynthesize and the reliance on external organic matter clearly align mushrooms with the definition of heterotrophs.

Another critical aspect of mushroom nutrition is their symbiotic relationships with other organisms. Many mushrooms form mutualistic associations, such as mycorrhizae, where they partner with plant roots. In these relationships, the mushroom provides the plant with essential nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen, which it absorbs from the soil, while the plant supplies the mushroom with carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis. This interdependence highlights the heterotrophic nature of mushrooms, as they still depend on organic compounds derived from other organisms, even in symbiotic scenarios.

It is important to note that while some mushrooms are saprotrophic, feeding on dead or decaying matter, others are parasitic, obtaining nutrients from living hosts. Regardless of their specific lifestyle, all mushrooms share the common trait of absorbing organic matter rather than producing it themselves. This distinguishes them from autotrophs like plants and cyanobacteria, which generate their own food. The diversity of mushroom species and their ecological roles further emphasizes their adaptability as heterotrophs, thriving in various environments by exploiting available organic resources.

In summary, mushrooms are quintessential heterotrophs because they lack the ability to photosynthesize and instead absorb organic matter from their environment. Their nutritional strategies, whether saprotrophic, parasitic, or symbiotic, all revolve around obtaining pre-formed organic compounds. This reliance on external sources of organic matter firmly places mushrooms within the heterotrophic domain, making them a unique and instructive example of this biological classification. Understanding their nutrition sources not only clarifies their heterotrophic nature but also highlights their ecological importance in nutrient cycling and ecosystem dynamics.

Psychedelic Brick Caps: Hallucinogenic or Not?

You may want to see also

Saprotrophic Nature: They decompose dead organisms, a key heterotrophic trait

Mushrooms, as fungi, exhibit a saprotrophic nature, which is a defining heterotrophic trait. Unlike autotrophs that produce their own food through processes like photosynthesis, heterotrophs rely on external sources of organic matter for nutrition. Saprotrophs, a subset of heterotrophs, specialize in breaking down dead and decaying organic material. Mushrooms play a crucial role in ecosystems by decomposing dead organisms, such as plants and animals, as well as other organic debris like fallen leaves and wood. This process not only allows mushrooms to obtain the nutrients they need to survive but also contributes to nutrient cycling in the environment.

The saprotrophic nature of mushrooms is facilitated by their secretion of enzymes that break down complex organic compounds into simpler forms. These enzymes are released into the substrate, where they degrade materials like cellulose, lignin, and proteins, which are abundant in dead plant and animal matter. The fungi then absorb the resulting nutrients, such as sugars and amino acids, directly through their hyphal networks. This efficient decomposition process highlights the heterotrophic reliance of mushrooms on external organic sources, as they lack the ability to synthesize their own food internally.

Mushrooms' role as decomposers is essential for ecosystem health and sustainability. By breaking down dead organisms, they prevent the accumulation of organic waste, which could otherwise lead to nutrient lockout and hinder plant growth. The nutrients released during decomposition are recycled back into the soil, where they become available to other organisms, including plants. This saprotrophic activity underscores the heterotrophic nature of mushrooms, as they are fundamentally dependent on the organic matter produced by other living or once-living organisms.

Furthermore, the saprotrophic behavior of mushrooms contrasts with other heterotrophic modes, such as parasitism or predation. While some fungi are parasitic, obtaining nutrients from living hosts, and others form mutualistic relationships (e.g., mycorrhizae), saprotrophic mushrooms focus exclusively on non-living organic material. This specialization makes them key players in the carbon cycle, as they help convert organic carbon from dead organisms into forms that can be reused by other life forms. Their reliance on external organic matter for energy and growth firmly establishes mushrooms as heterotrophs.

In summary, the saprotrophic nature of mushrooms—their ability to decompose dead organisms—is a quintessential heterotrophic trait. Through enzymatic breakdown of organic material, mushrooms obtain nutrients while simultaneously contributing to ecosystem processes like nutrient cycling and waste decomposition. This reliance on external organic sources for sustenance distinguishes them from autotrophs and highlights their role as primary decomposers in various habitats. Thus, mushrooms exemplify heterotrophy through their saprotrophic lifestyle, making them a vital component of the natural world.

Mushroom's Spoilage: How Long Do They Last?

You may want to see also

Mycorrhizal Relationships: Symbiotic with plants, still rely on external carbon sources

Mushrooms, like most fungi, are heterotrophs, meaning they cannot produce their own food through photosynthesis and must obtain organic compounds from external sources. This fundamental characteristic is central to understanding mycorrhizal relationships, where fungi form symbiotic associations with plant roots. In these relationships, fungi enhance the plant’s ability to absorb water and nutrients, particularly phosphorus and nitrogen, from the soil. However, despite this mutualistic partnership, the fungi still rely on external carbon sources, primarily derived from the plant itself. The plant provides carbohydrates produced via photosynthesis to the fungus, which in turn supports the fungus’s metabolic needs.

Mycorrhizal relationships are categorized into several types, including arbuscular, ectomycorrhizal, and ericoid mycorrhizae, each differing in structure and function. In all cases, the fungus extends its hyphal network into the soil, increasing the surface area for nutrient absorption. This network is far more efficient than plant roots alone, allowing the plant to access nutrients that would otherwise be unavailable. In exchange, the fungus receives carbon-rich compounds from the plant, typically in the form of sugars or lipids. This exchange highlights the heterotrophic nature of the fungus, as it depends on the plant for its carbon requirements.

The reliance on external carbon sources underscores the fungus’s inability to synthesize its own organic compounds. While the mycorrhizal relationship is symbiotic, with both parties benefiting, the fungus is still fundamentally dependent on the plant for survival. This dependency is particularly evident in ectomycorrhizal fungi, which often form sheaths around plant roots and are less capable of surviving independently. Even in cases where fungi can decompose organic matter or absorb nutrients from the environment, their primary carbon source in mycorrhizal relationships remains the plant.

The heterotrophic nature of fungi in mycorrhizal relationships also has ecological implications. These associations play a critical role in nutrient cycling within ecosystems, as fungi facilitate the transfer of nutrients from the soil to plants. However, this process is energy-intensive for the fungus, necessitating a steady supply of carbon from the plant. Without this external carbon source, the fungus would be unable to sustain its metabolic activities or support the mycorrhizal partnership. Thus, the heterotrophic lifestyle of fungi is a key factor in the dynamics of mycorrhizal relationships.

In summary, mycorrhizal relationships exemplify the heterotrophic nature of mushrooms and fungi, as they rely on external carbon sources provided by their plant partners. While these symbiotic associations are mutually beneficial, the fungus’s inability to produce its own carbon compounds underscores its dependency on the plant. This relationship is essential for nutrient uptake in plants and nutrient cycling in ecosystems, highlighting the ecological significance of fungal heterotrophy. Understanding this dynamic provides valuable insights into the role of fungi as heterotrophs in both plant biology and environmental processes.

Mushrooms: Nature's Source of Vitamin D

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Lack of Chlorophyll: No chlorophyll means no photosynthesis, confirming heterotrophy

Mushrooms, like all fungi, lack chlorophyll, the green pigment found in plants and some algae that is essential for photosynthesis. Chlorophyll plays a critical role in capturing sunlight and converting it into chemical energy through the process of photosynthesis. This energy is then used to synthesize organic compounds, such as glucose, from carbon dioxide and water. Since mushrooms do not possess chlorophyll, they are incapable of performing photosynthesis, which immediately distinguishes them from autotrophic organisms like plants and certain bacteria. This fundamental absence of chlorophyll is a key indicator of their heterotrophic nature, as it forces them to rely on external sources for their nutritional needs.

The lack of chlorophyll in mushrooms directly confirms their heterotrophic lifestyle because it eliminates their ability to produce their own food. Heterotrophs are organisms that cannot synthesize their own organic nutrients and must obtain them by consuming other organic matter. In the case of mushrooms, they achieve this through the secretion of enzymes that break down complex organic materials, such as dead plant and animal matter, into simpler substances that can be absorbed. This process, known as extracellular digestion, is a hallmark of heterotrophic fungi. Without the capacity for photosynthesis, mushrooms are entirely dependent on this mechanism to acquire the energy and nutrients necessary for growth and survival.

Furthermore, the absence of chlorophyll in mushrooms highlights their ecological role as decomposers. In ecosystems, fungi play a vital role in breaking down organic debris, recycling nutrients back into the environment, and facilitating nutrient cycling. This decomposer role is a direct consequence of their heterotrophic nature, as they must derive their energy from pre-existing organic matter. Unlike autotrophs, which contribute to the primary production of ecosystems by converting inorganic compounds into organic ones, heterotrophic fungi like mushrooms are involved in secondary production, relying on the organic compounds produced by other organisms.

The structural adaptations of mushrooms also reflect their heterotrophic lifestyle and lack of chlorophyll. Unlike plants, which have leaves and other structures optimized for light absorption, mushrooms have mycelium—a network of thread-like hyphae—that spreads through substrates to absorb nutrients. This mycelium is highly efficient at extracting organic compounds from the environment, further emphasizing their dependence on external sources of nutrition. The fruiting bodies of mushrooms, which are the visible parts we commonly see, are primarily reproductive structures rather than photosynthetic organs, reinforcing the idea that fungi are not capable of photosynthesis.

In summary, the lack of chlorophyll in mushrooms is a definitive confirmation of their heterotrophic nature. Without chlorophyll, they cannot perform photosynthesis, which necessitates their reliance on external organic matter for energy and nutrients. This characteristic not only distinguishes them from autotrophic organisms but also defines their ecological role as decomposers. The structural and functional adaptations of mushrooms, such as their mycelium and extracellular digestion processes, further underscore their heterotrophic lifestyle, making them a clear example of organisms that depend on other sources for their nutritional needs.

Reconstituting Wild Mushrooms: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Energy Acquisition: Mushrooms obtain energy from pre-formed organic compounds, not sunlight

Mushrooms, like all fungi, are heterotrophs, meaning they cannot produce their own food through photosynthesis. Unlike plants, which use sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide to synthesize organic compounds, mushrooms lack chlorophyll and the necessary cellular machinery for this process. Instead, mushrooms acquire energy by breaking down and absorbing pre-formed organic compounds from their environment. This fundamental difference in energy acquisition distinguishes mushrooms from autotrophs like plants and underscores their classification as heterotrophs.

The primary mechanism by which mushrooms obtain energy involves the secretion of enzymes into their surroundings. These enzymes break down complex organic materials, such as dead plant matter, wood, or even animal remains, into simpler molecules like sugars and amino acids. This process, known as extracellular digestion, allows mushrooms to access nutrients that are already present in their environment. The resulting nutrients are then absorbed directly through the fungal hyphae, the thread-like structures that make up the mushroom's body. This method of energy acquisition highlights the mushroom's reliance on external organic sources rather than internal synthesis.

Mushrooms are particularly efficient at decomposing lignin and cellulose, two tough components of plant cell walls that many other organisms cannot break down. This ability makes them key players in nutrient cycling within ecosystems, as they help return organic matter to the soil in a form that other organisms can use. However, this process also reinforces their status as heterotrophs, as they depend entirely on the organic materials produced by other organisms, either living or dead, to meet their energy needs.

Another important aspect of mushroom energy acquisition is their symbiotic relationships with other organisms. For example, mycorrhizal fungi form mutualistic associations with plant roots, where the fungus helps the plant absorb water and minerals from the soil, while the plant provides the fungus with carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis. In this case, the mushroom still relies on pre-formed organic compounds (from the plant) rather than sunlight for energy. Similarly, some mushrooms are parasitic, obtaining nutrients from living hosts, but again, they are dependent on external organic sources.

In summary, mushrooms obtain energy exclusively from pre-formed organic compounds, not sunlight, which firmly establishes them as heterotrophs. Their inability to photosynthesize, combined with their reliance on extracellular digestion and symbiotic or parasitic relationships, underscores their unique mode of energy acquisition. This characteristic not only defines their ecological role as decomposers and symbionts but also highlights their distinct place in the biological classification of organisms. Understanding this aspect of mushroom biology is essential for appreciating their contributions to ecosystems and their differences from other life forms.

Microwave Mushrooms: Unveiling the Flashing Phenomenon and Its Causes

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, mushrooms are heterotrophs. They cannot produce their own food through photosynthesis like plants (autotrophs) and instead obtain nutrients by breaking down organic matter in their environment.

Mushrooms obtain nutrients by secreting enzymes into their surroundings to break down dead or decaying organic material, such as wood, leaves, or soil, and then absorbing the released nutrients.

Yes, all fungi, including mushrooms, are heterotrophs. They rely on external sources of organic matter for energy and nutrients, as they lack chlorophyll and cannot perform photosynthesis.