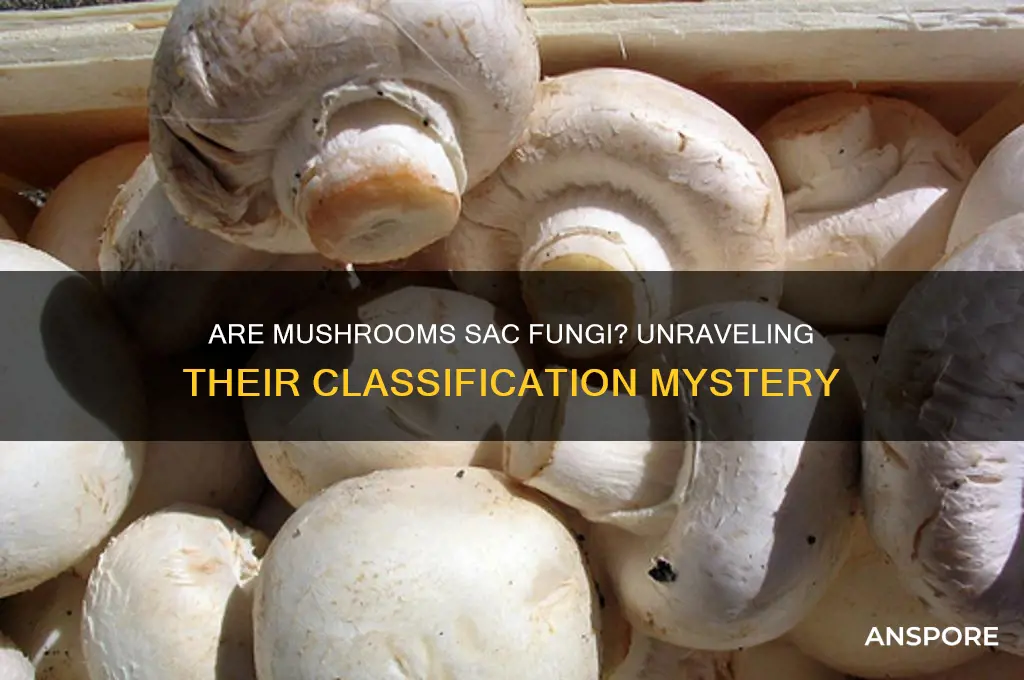

Mushrooms are often a subject of curiosity when it comes to their classification in the fungal kingdom. While many people associate mushrooms with the familiar umbrella-shaped fruiting bodies, their taxonomic placement is more nuanced. Mushrooms are indeed classified within the group known as Basidiomycota, commonly referred to as club fungi, due to the club-shaped structures (basidia) where their spores develop. This distinguishes them from Ascomycota, or sac fungi, which produce spores in sac-like structures called asci. Although mushrooms and sac fungi both belong to the broader kingdom of Fungi, they are separate taxonomic groups with distinct reproductive mechanisms and morphological characteristics. Understanding this classification helps clarify why mushrooms are not considered sac fungi, despite both being integral parts of the fungal world.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Classification | Mushrooms are not classified as sac fungi (Ascomycota). They belong to the phylum Basidiomycota, commonly known as club fungi. |

| Reproductive Structures | Mushrooms produce spores in club-like structures called basidia, whereas sac fungi produce spores in sac-like structures called asci. |

| Spore Formation | Mushrooms release spores externally from basidia, while sac fungi release spores from within asci. |

| Examples | Mushrooms (Agaricus, Amanita) vs. Sac Fungi (yeasts, morels, truffles). |

| Ecological Roles | Mushrooms often form mycorrhizal relationships with plants, while sac fungi include decomposers, parasites, and symbionts. |

| Economic Importance | Mushrooms are widely cultivated for food, while sac fungi include important species like baker's yeast and penicillin-producing molds. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Mushroom vs. Sac Fungi: Key Differences

Mushrooms and sac fungi (Ascomycota) are both members of the fungal kingdom, but they belong to different taxonomic groups and exhibit distinct characteristics. Mushrooms primarily fall under the Basidiomycota phylum, while sac fungi are classified under the Ascomycota phylum. This fundamental difference in classification highlights their unique evolutionary paths and biological features. Although both groups are fungi, their reproductive structures, ecological roles, and physical attributes set them apart.

One of the key differences between mushrooms and sac fungi lies in their reproductive mechanisms. Mushrooms, as basidiomycetes, produce spores on structures called basidia, which are club-shaped cells typically found on the gills or pores of the mushroom cap. In contrast, sac fungi produce spores within sac-like structures called asci (singular: ascus), which are often arranged in fruiting bodies such as cups, flasks, or powdery masses. This distinction in spore-bearing structures is a defining feature used to differentiate between the two groups.

Morphologically, mushrooms are easily recognizable by their fruiting bodies, which consist of a cap (pileus), stem (stipe), and gills or pores underneath the cap. These structures are adapted for spore dispersal and are often visible above ground. Sac fungi, however, exhibit a wider variety of forms, ranging from cup fungi (e.g., Peziza) to powdery mildews and truffles. Their fruiting bodies are often less conspicuous and may be embedded in substrates like soil, wood, or plant tissues. This diversity in form reflects the varied ecological niches occupied by sac fungi.

Ecologically, mushrooms and sac fungi play different roles in their environments. Many mushrooms are decomposers, breaking down organic matter such as wood and leaves, while others form mutualistic relationships with plants (e.g., mycorrhizal fungi). Sac fungi also include decomposers, but they are more prominently known for their roles as parasites (e.g., causing diseases in plants and animals) and symbionts (e.g., lichens). Additionally, sac fungi are responsible for producing many industrially important compounds, such as penicillin and other antibiotics.

In summary, while mushrooms and sac fungi share a common fungal ancestry, they differ significantly in their classification, reproductive structures, morphology, and ecological roles. Mushrooms, as basidiomycetes, are characterized by their basidia and familiar fruiting bodies, whereas sac fungi, as ascomycetes, produce spores in asci and exhibit a broader range of forms and functions. Understanding these differences is essential for appreciating the diversity and complexity of the fungal kingdom.

Medicinal Mushrooms: Nutritional Supplement or Functional Food?

You may want to see also

Taxonomic Classification of Mushrooms

The taxonomic classification of mushrooms is a complex and fascinating subject, rooted in the biological organization of fungi. Mushrooms, which are the fruiting bodies of certain fungi, belong to the kingdom Fungi, a distinct group of eukaryotic organisms separate from plants, animals, and bacteria. Within the kingdom Fungi, mushrooms are classified under the division Basidiomycota, often referred to as the "club fungi." This classification is based on their method of sexual reproduction, which involves the formation of basidiospores on club-like structures called basidia. However, the question of whether mushrooms are classified as sac fungi (which belong to the division Ascomycota) is a common point of confusion. The answer is no—mushrooms are not sac fungi. Sac fungi reproduce via asci, sac-like structures that contain ascospores, whereas mushrooms reproduce via basidia.

The taxonomic hierarchy of mushrooms begins with the domain Eukarya, as they possess membrane-bound organelles and a nucleus. Within the kingdom Fungi, mushrooms are further categorized into the subkingdom Dikarya, which includes fungi that produce dikaryotic mycelium (cells with two haploid nuclei). As mentioned, mushrooms fall under the division Basidiomycota, one of the two major divisions of fungi that undergo sexual reproduction. This division is then subdivided into classes, such as Agaricomycetes, which encompasses the majority of mushroom-forming species, including familiar genera like *Agaricus* (button mushrooms) and *Boletus*. These classes are further divided into orders, families, genera, and finally species, each level providing greater specificity in classification.

The distinction between mushrooms and sac fungi is crucial for understanding their taxonomic placement. Sac fungi, belonging to the division Ascomycota, include a wide range of organisms such as yeasts, truffles, and molds like *Penicillium*. Their reproductive structures (asci) are fundamentally different from those of mushrooms. While both groups are fungi, their evolutionary paths and reproductive strategies have led to their classification into separate divisions. This highlights the diversity within the fungal kingdom and the importance of precise taxonomic categorization.

In the context of mushrooms, their classification within Basidiomycota is supported by molecular and morphological evidence. For example, DNA sequencing has confirmed the evolutionary relationships between different mushroom species, reinforcing their placement in this division. Additionally, the presence of basidia and basidiospores is a defining characteristic that distinguishes mushrooms from other fungal groups. Understanding this classification is essential for fields like mycology, ecology, and biotechnology, as it provides a framework for studying fungal diversity and function.

Finally, it is worth noting that the taxonomic classification of fungi, including mushrooms, is continually evolving as new research emerges. Advances in molecular biology and genomics have led to revisions in fungal taxonomy, sometimes reclassifying species or clarifying relationships between groups. Despite these changes, the core distinction between mushrooms (Basidiomycota) and sac fungi (Ascomycota) remains a fundamental concept in fungal taxonomy. This clarity ensures that discussions about mushrooms and their classification remain accurate and scientifically grounded.

The Mushroom House: A Magical Space with Many Rooms

You may want to see also

Sac Fungi (Ascomycota) Characteristics

Sac Fungi, formally known as Ascomycota, represent one of the largest and most diverse groups within the fungal kingdom. They are characterized by the production of asci, which are microscopic, sac-like structures that contain spores. These asci are a defining feature of the phylum and play a crucial role in the reproductive cycle of these fungi. Unlike mushrooms, which belong to the Basidiomycota phylum and produce spores on club-like structures called basidia, Ascomycota fungi enclose their spores within asci, typically arranged in fruiting bodies such as ascocarps. This fundamental difference in spore-bearing structures is a key factor in distinguishing sac fungi from mushrooms.

The life cycle of Ascomycota is complex and involves both sexual and asexual reproduction. During sexual reproduction, compatible hyphae (filamentous structures) fuse, leading to the formation of a zygote that develops into an ascus. Each ascus typically contains eight spores, known as ascospores, which are released upon maturity to disperse and colonize new environments. Asexual reproduction in sac fungi often involves the production of conidia, which are spores formed at the tips or sides of specialized hyphae. This dual reproductive strategy allows Ascomycota to adapt to a wide range of ecological niches, from soil and decaying matter to symbiotic relationships with plants and animals.

Morphologically, Ascomycota exhibit a wide variety of forms, ranging from unicellular yeasts to multicellular molds and cup-like or flask-shaped fruiting bodies. Examples of sac fungi include morels, truffles, and cup fungi, which produce visible fruiting bodies, as well as microscopic species like powdery mildew and baker's yeast. Their fruiting bodies, or ascocarps, can vary in structure and are often classified into types such as perithecia (flask-shaped), apothecia (cup-shaped), and cleistothecia (closed spheres). These structures protect the asci and facilitate spore dispersal, ensuring the survival and propagation of the species.

Ecologically, Ascomycota play vital roles in nutrient cycling, decomposition, and symbiotic relationships. Many species are saprobes, breaking down organic matter and recycling nutrients in ecosystems. Others form mutualistic associations, such as mycorrhizae with plant roots, enhancing nutrient uptake for their hosts. Some sac fungi are also pathogens, causing diseases in plants, animals, and humans, while others are economically important in industries like food production (e.g., yeast in baking and brewing) and biotechnology.

In summary, sac fungi (Ascomycota) are distinguished by their ascus-producing reproductive structures, diverse morphologies, and ecological significance. While mushrooms belong to a different phylum (Basidiomycota), Ascomycota encompass a vast array of species with unique characteristics and functions. Understanding these features is essential for appreciating the role of sac fungi in biology, ecology, and human endeavors.

Keep Mushrooms Away: Healthy Lawn, Happy Garden

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Mushrooms in Basidiomycota Phylum

Mushrooms are a diverse group of fungi, and their classification is primarily within the Basidiomycota phylum, not the Ascomycota (sac fungi) phylum. While some fungi, like yeasts and morels, belong to the Ascomycota and are indeed classified as sac fungi due to their sac-like structures (asci) that produce spores, mushrooms typically fall under Basidiomycota. This phylum is characterized by the production of spores on club-like structures called basidia, which give the group its name. Understanding this distinction is crucial for anyone studying fungi or foraging for mushrooms, as it highlights the unique reproductive and structural features of these organisms.

The Basidiomycota phylum encompasses a wide range of fungi, including most of the mushrooms commonly encountered in forests, fields, and gardens. These mushrooms are distinguished by their life cycle, which involves the formation of a basidiocarp (the fruiting body, or mushroom) that produces basidiospores. These spores are externally borne on basidia, unlike the enclosed spores of sac fungi. Examples of Basidiomycota mushrooms include the familiar button mushrooms (*Agaricus bisporus*), shiitakes (*Lentinula edodes*), and the iconic fly agaric (*Amanita muscaria*). Each of these mushrooms plays a unique ecological role, such as decomposing organic matter or forming symbiotic relationships with plants.

One of the most fascinating aspects of mushrooms in the Basidiomycota phylum is their ecological importance. Many basidiomycetes are decomposers, breaking down complex organic materials like wood and leaf litter, which recycles nutrients back into ecosystems. Others form mutualistic relationships with plants, such as mycorrhizal associations, where the fungus helps the plant absorb water and nutrients in exchange for carbohydrates. This symbiotic relationship is vital for the health of forests and agricultural systems. Additionally, some basidiomycetes are parasites, causing diseases in plants and even insects, showcasing the phylum's diverse ecological roles.

Morphologically, mushrooms in Basidiomycota exhibit a wide range of forms and structures. The fruiting bodies can vary from the typical umbrella-shaped caps and stems to more unusual forms like shelf-like brackets (e.g., *Ganoderma*) or coral-like structures (e.g., *Clavulina*). The gills, pores, or spines underneath the cap are where basidia and spores develop, and these features are key for identification. For instance, mushrooms in the genus *Agaricus* have gills, while those in *Boletus* have pores. These characteristics, along with spore color and microscopic features, are essential for classifying mushrooms within the Basidiomycota phylum.

In summary, mushrooms in the Basidiomycota phylum are distinct from sac fungi due to their reproductive structures and ecological roles. Their classification is based on the presence of basidia and basidiospores, which set them apart from the asci and ascospores of Ascomycota. Whether decomposing matter, forming symbiotic relationships, or producing edible fruiting bodies, basidiomycetes are integral to ecosystems worldwide. Understanding their unique features not only aids in identification but also highlights their importance in biological processes and human applications, such as food, medicine, and environmental restoration.

Mushrooms: Veggies or Not?

You may want to see also

Why Mushrooms Are Not Sac Fungi

Mushrooms and sac fungi (Ascomycota) are both members of the fungal kingdom, but they belong to distinct taxonomic groups with unique characteristics. Mushrooms are primarily classified under the Basidiomycota phylum, commonly known as basidiomycetes or club fungi. In contrast, sac fungi belong to the Ascomycota phylum, characterized by the formation of sac-like structures called asci, which contain their spores. This fundamental difference in spore-bearing structures is the first clue to why mushrooms are not classified as sac fungi. While both groups are fungi, their reproductive mechanisms and morphological features set them apart.

One of the most significant distinctions between mushrooms and sac fungi lies in their spore production. Basidiomycetes, including mushrooms, produce spores on club-shaped structures called basidia, typically located on the gills or pores of the mushroom cap. These spores are externally released and dispersed. In contrast, sac fungi produce spores inside asci, which are sac-like cells that rupture to release the spores. This internal spore formation and release mechanism is exclusive to Ascomycota and does not occur in mushrooms. Therefore, the absence of asci in mushrooms is a clear indicator that they do not belong to the sac fungi group.

Morphologically, mushrooms and sac fungi also differ in their fruiting bodies. Mushrooms typically have a well-defined cap and stem structure, which is a characteristic feature of basidiomycetes. Sac fungi, on the other hand, often produce fruiting bodies that are more diverse in form, such as cup-like structures (e.g., morels) or powdery masses (e.g., powdery mildews). While some sac fungi may superficially resemble mushrooms, their internal structures and spore-bearing mechanisms confirm their classification as Ascomycota rather than Basidiomycota.

Another key difference is the ecological roles and habitats of mushrooms and sac fungi. Mushrooms are often associated with decomposing organic matter, mycorrhizal relationships with plants, or parasitic interactions. Sac fungi, however, exhibit a broader range of lifestyles, including saprophytic, parasitic, and symbiotic relationships. For example, many sac fungi are plant pathogens, such as those causing apple scab or ergot, while others are essential in food production, like yeast used in baking and brewing. These diverse ecological roles further emphasize the distinction between mushrooms and sac fungi.

In summary, mushrooms are not classified as sac fungi due to their distinct taxonomic placement in the Basidiomycota phylum, their unique spore-bearing structures (basidia vs. asci), and their morphological and ecological differences. While both groups are fungi, their reproductive strategies and characteristics clearly differentiate mushrooms from sac fungi. Understanding these distinctions is essential for accurate classification and appreciation of the diversity within the fungal kingdom.

Alcohol and Shrooms: A Risky Mix?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, mushrooms are not classified as sac fungi. Mushrooms belong to the phylum Basidiomycota, while sac fungi belong to the phylum Ascomycota.

Sac fungi (Ascomycota) are characterized by their spore-producing structures called asci, which release spores through a small pore. Mushrooms, on the other hand, belong to Basidiomycota and produce spores on club-like structures called basidia.

Yes, both mushrooms and sac fungi can be found in similar environments, such as forests, soil, and decaying organic matter. However, their reproductive structures and life cycles differ significantly.

Yes, some sac fungi are edible, such as morels (Morchella spp.) and truffles (Tuber spp.), which are highly prized in culinary traditions. However, many sac fungi are not edible and can be toxic or inedible.