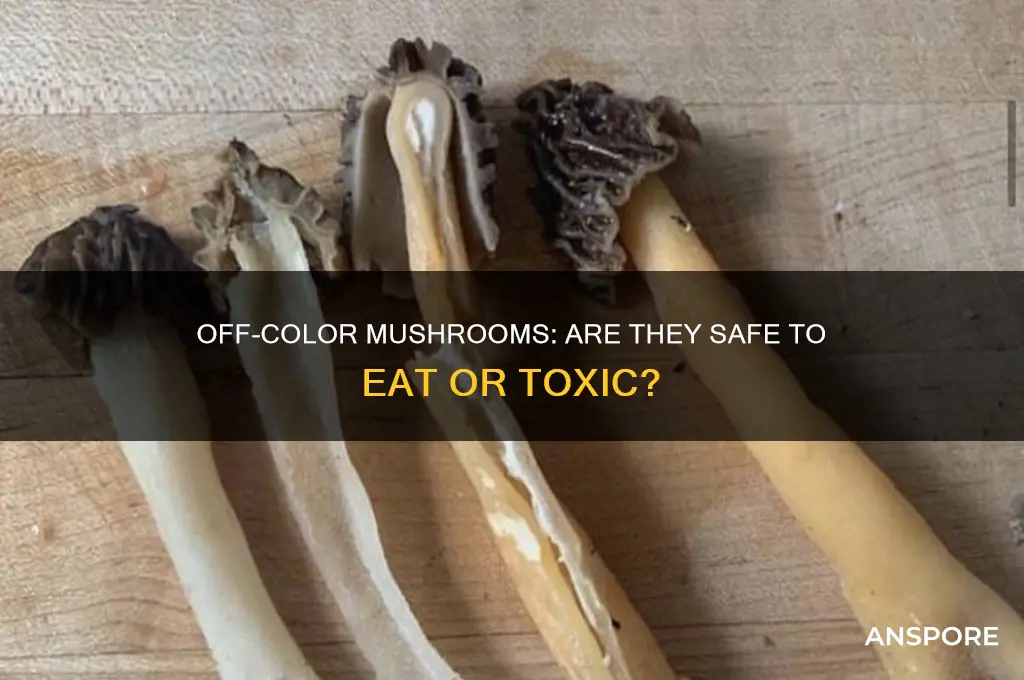

When encountering mushrooms with unusual or off-color appearances, it’s natural to question their safety. While some off-color mushrooms may simply be the result of environmental factors like sunlight exposure, bruising, or aging, others could indicate spoilage, toxicity, or the presence of harmful molds. For instance, vibrant greens or blues might signal the presence of toxins, while slimy textures or foul odors often suggest decay. Without proper identification, consuming off-color mushrooms can pose serious health risks, including poisoning or allergic reactions. Therefore, it’s crucial to rely on expert guidance or avoid them altogether, as the adage goes: When in doubt, throw it out.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Edibility | Off-color mushrooms can be edible or poisonous. Color alone is not a reliable indicator of edibility. |

| Causes of Off-Color | Environmental factors (soil, humidity, light), genetic variations, bruising, aging, or contamination. |

| Common Off-Colors | Yellow, brown, blue, green, or reddish hues compared to typical species color. |

| Toxicity Risk | Some poisonous mushrooms have unusual colors, but many edible mushrooms also exhibit color variations. |

| Identification | Requires examination of other features: cap shape, gill structure, spore color, smell, habitat, and expert consultation. |

| General Advice | Avoid consuming mushrooms with unusual colors unless positively identified by an expert. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Identifying Safe vs. Toxic Mushrooms

Mushroom color alone isn’t a reliable indicator of safety, but unusual hues often signal caution. For instance, bright green or yellow mushrooms might contain toxins like batrachotoxin, found in certain poisonous species like the infamous Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*). While some edible mushrooms, like the Lion’s Mane, have off-white or yellowish tones, their textures and habitats differentiate them from toxic lookalikes. The key takeaway? Color should prompt further investigation, not immediate dismissal or consumption.

To identify safe mushrooms, start with habitat and seasonality. Edible species like chanterelles thrive in wooded areas under specific trees, while toxic varieties often grow near decaying matter or in unusual locations. For example, the Jack-O’-Lantern mushroom, with its bright orange glow, resembles chanterelles but grows on wood and causes severe gastrointestinal distress if ingested. Always cross-reference color with other characteristics like gill structure, spore print, and smell. A spore print—obtained by placing the cap on paper overnight—can reveal critical differences: white or brown prints are common in edible species, while green or black prints often indicate toxicity.

Children and pets are particularly vulnerable to mushroom poisoning, as they’re more likely to ingest unfamiliar fungi. Teach kids to avoid touching or tasting wild mushrooms, and keep pets on leashes in areas where mushrooms grow. If accidental ingestion occurs, note the mushroom’s color, size, and location for identification. Immediate symptoms like nausea, vomiting, or dizziness warrant a call to poison control or a veterinarian. Remember, even small doses of certain toxins can be fatal—the Death Cap, for instance, contains amatoxins that cause liver failure within 24–48 hours.

Foraging safely requires a multi-step approach. First, use field guides or apps like iNaturalist to match findings with known species. Second, consult local mycological societies or experts for verification. Third, cook mushrooms thoroughly, as heat can neutralize some toxins. However, avoid tasting or cooking mushrooms of uncertain identity—some toxins remain active even after cooking. Finally, start with easily identifiable species like morels or oyster mushrooms before attempting more complex varieties. Off-color mushrooms, while intriguing, should be left to the experts unless positively identified as safe.

Mushrooms and Pets: Are They a Dangerous Combination?

You may want to see also

Common Off-Color Varieties Explained

Mushrooms with unusual colors often spark curiosity and concern, but not all off-color varieties are harmful. For instance, the Albino Penis Envy mushroom, a rare strain of Psilocybe cubensis, lacks pigmentation due to a genetic mutation. Its pale appearance doesn’t indicate toxicity; instead, it’s prized for its potency, containing up to 2% psilocybin. However, its strength requires caution—start with a microdose (0.1–0.3 grams) to assess tolerance before consuming larger amounts. Always verify the species, as some white mushrooms, like the deadly Amanita bisporigera, are lethal.

In contrast, blue-staining mushrooms like Psilocybe cyanescens develop a bluish hue when bruised due to psilocin oxidation. This color change is a natural defense mechanism, not a sign of spoilage. While these mushrooms are safe for consumption, their potency varies widely. A single gram can contain 0.5–2% psilocybin, so beginners should start with half a gram to avoid overwhelming effects. Always harvest from uncontaminated areas, as environmental toxins can accumulate in wild mushrooms.

Yellow or brown discoloration in mushrooms like Agaricus bisporus (button mushrooms) often results from enzymatic browning or aging. While these mushrooms are still edible, their texture and flavor degrade over time. To preserve freshness, store them in a paper bag in the refrigerator for up to 5 days. Avoid consuming slimy or foul-smelling specimens, as these signs indicate bacterial growth. For culinary use, lightly sauté discolored button mushrooms to enhance flavor and mask imperfections.

Finally, red or orange mushrooms like Lactarius deliciosus (Saffron Milk Cap) are prized for their vibrant color and nutty flavor. However, not all red mushrooms are safe—some, like Amanita muscaria, are toxic. Always cook Lactarius deliciosus thoroughly, as raw consumption can cause digestive discomfort. Pair it with hearty dishes like risotto or stews to highlight its earthy taste. When foraging, carry a field guide and consult an expert to avoid misidentification, as even experienced foragers can mistake toxic species for edible ones.

Mushrooms and Illness: Are They Safe When You're Feeling Sick?

You may want to see also

Color Changes Due to Aging

Mushrooms, like all living organisms, undergo changes as they age, and one of the most noticeable transformations is in their color. This phenomenon is not merely a cosmetic alteration but can serve as a critical indicator of a mushroom's freshness, safety, and nutritional value. For instance, the vibrant white caps of button mushrooms may darken to a tan or brown as they mature, a process often accompanied by a firmer texture and more pronounced flavor. Understanding these changes is essential for both culinary enthusiasts and foragers, as it can help distinguish between a perfectly aged mushroom and one that has begun to spoil.

From an analytical perspective, the color changes in aging mushrooms are primarily due to enzymatic browning, a chemical reaction that occurs when enzymes in the mushroom cells interact with oxygen. This process, similar to what happens when an apple slice turns brown, is accelerated by factors such as exposure to air, light, and temperature fluctuations. For example, shiitake mushrooms may develop darker, more pronounced gills and caps as they age, which can enhance their umami flavor but also signal that they are past their prime for certain recipes. Monitoring these changes can help chefs and home cooks determine the best use for mushrooms at different stages of their lifecycle.

For those who forage wild mushrooms, recognizing age-related color changes is a skill that can mean the difference between a safe meal and a risky one. Take the chanterelle, a prized edible mushroom known for its golden-yellow hue. As it ages, its color may fade to a pale yellow or even white, and its flesh may become softer and more susceptible to decay. While an older chanterelle might still be edible, its texture and flavor will be less desirable, and there’s an increased risk of confusion with toxic look-alikes. Foragers should always err on the side of caution and avoid mushrooms with ambiguous color changes or signs of deterioration.

Practical tips for managing aging mushrooms include proper storage to slow down the color-changing process. Store mushrooms in a paper bag in the refrigerator, as this allows them to breathe while absorbing excess moisture, which can prolong their freshness. Avoid washing mushrooms until just before use, as excess water accelerates spoilage and color changes. If you notice mushrooms beginning to darken, consider using them in cooked dishes rather than raw applications, as cooking can mitigate textural changes and enhance flavors. For example, slightly aged portobello mushrooms, with their deeper brown caps, are ideal for grilling or stuffing, as the intensified flavor complements hearty recipes.

In conclusion, while off-color mushrooms are not always bad, understanding the natural color changes due to aging is crucial for making informed decisions. Whether you’re selecting mushrooms at the market, foraging in the wild, or storing them at home, recognizing these changes can help you maximize their culinary potential while ensuring safety. By combining scientific knowledge with practical techniques, you can appreciate the full lifecycle of mushrooms and use them at their best, regardless of their age.

Are Mushroom Drugs Harmful? Exploring Psilocybin's Risks and Benefits

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$23.49 $39.95

Environmental Factors Affecting Pigment

Mushrooms, like all living organisms, are influenced by their environment, and this influence extends to their pigmentation. The color of a mushroom is not just a matter of aesthetics; it can be a crucial indicator of its species, maturity, and even safety. Environmental factors play a significant role in determining the pigment of mushrooms, and understanding these factors can help foragers and enthusiasts make informed decisions.

Light Exposure and Pigment Development

One of the most direct environmental influences on mushroom pigmentation is light exposure. Many mushroom species require specific light conditions to develop their characteristic colors. For instance, *Coprinus comatus* (the shaggy mane mushroom) produces darker pigments when exposed to higher light levels. Conversely, some species may bleach or fade in intense sunlight. For foragers, this means that mushrooms found in shaded areas might differ in color from those in open fields, even if they are the same species. To preserve pigment accuracy for identification, store freshly picked mushrooms in a cool, dark place until examination.

Temperature and Humidity: The Hidden Drivers

Temperature and humidity are silent architects of mushroom pigmentation. Cooler temperatures often slow down metabolic processes, leading to more intense colors as pigments accumulate over time. For example, *Amanita muscaria* (the fly agaric) tends to display brighter reds in colder climates. Humidity, on the other hand, affects the mushroom’s ability to retain moisture, which can impact pigment distribution. High humidity environments may result in more vibrant, evenly colored caps, while drier conditions can cause uneven or faded hues. For optimal pigment observation, collect mushrooms during periods of stable weather, avoiding extreme temperature fluctuations.

Soil Composition and Nutrient Availability

The soil in which mushrooms grow is a treasure trove of nutrients that directly influence pigment production. Minerals like iron, copper, and manganese are essential cofactors for enzymes involved in pigment synthesis. For instance, *Boletus edulis* (porcini) often exhibits richer browns in soil rich in organic matter. Conversely, nutrient-poor soil may lead to paler or atypical colors. Foragers should note that mushrooms growing near industrial areas or polluted soil may have abnormal pigments due to heavy metal contamination, a red flag for potential toxicity. Always avoid mushrooms from areas with known environmental contaminants.

Practical Tips for Foragers

When assessing off-color mushrooms, consider the environmental context. A mushroom with unusual pigmentation might be a rare variant, a sign of stress, or an indicator of toxicity. For example, *Agaricus bisporus* (button mushrooms) can turn greenish when bruised due to enzymatic reactions, not necessarily indicating spoilage. However, a normally white mushroom turning yellow without bruising could signal decay. Always cross-reference color changes with other factors like texture, smell, and habitat. If in doubt, discard the mushroom—misidentification can have serious health consequences.

By understanding how environmental factors shape mushroom pigmentation, foragers can make safer and more informed decisions. While off-color mushrooms aren’t always bad, their appearance should prompt careful scrutiny rather than assumption.

Spotting Spoiled White Mushrooms: Signs of Badness and Freshness Tips

You may want to see also

Health Risks of Consuming Discolored Mushrooms

Mushrooms that deviate from their typical color can signal underlying issues, ranging from harmless environmental factors to dangerous toxins. While some discoloration, like browning from oxidation, is benign, others—such as green, yellow, or black hues—may indicate bacterial contamination or mold growth. For instance, *Clitocybe dealbata*, a mushroom with a greenish tint, contains muscarine, a toxin causing sweating, salivation, and blurred vision. Recognizing these color changes is the first step in assessing potential health risks.

Analyzing the cause of discoloration requires understanding mushroom biology. Environmental stressors like excessive moisture or sunlight can alter pigmentation without introducing toxins. However, internal discoloration often stems from microbial invasion or toxin production. For example, the *Galerina* species, which can resemble harmless mushrooms, may develop yellow or brown spots due to the presence of amatoxins—deadly compounds causing liver failure within 24–48 hours of ingestion. Even small doses (as little as 0.1 mg/kg of body weight) can be fatal if untreated.

To minimize risks, follow these practical steps: inspect mushrooms for uniform color and texture, avoid those with slimy surfaces or unusual odors, and discard any with visible mold or discoloration. Cooking does not always neutralize toxins; amatoxins, for instance, remain potent even after boiling. If unsure, consult a mycologist or use a reliable field guide. For foragers, stick to well-known edible varieties like *Agaricus bisporus* (button mushrooms) and avoid experimenting with unfamiliar species.

Comparing discolored mushrooms to their safe counterparts highlights the importance of vigilance. While a slightly off-color *Boletus edulis* (porcini) might still be edible, a discolored *Amanita phalloides* (death cap) is a ticking time bomb. The latter’s greenish or yellowish hues often coincide with peak toxin levels. Even experienced foragers have mistaken toxic species for edible ones due to misleading coloration, underscoring the need for caution.

In conclusion, discolored mushrooms are not inherently dangerous, but their altered appearance warrants scrutiny. By understanding the causes of discoloration, recognizing high-risk species, and adopting safe handling practices, consumers can mitigate health risks. When in doubt, err on the side of caution—the consequences of misidentification can be severe, particularly for children or the elderly, who are more susceptible to toxin-induced complications. Always prioritize certainty over curiosity in mushroom consumption.

Are Mushrooms Safe for Dogs? Risks and Precautions Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Not necessarily. Some mushrooms naturally vary in color due to species, age, or environmental factors. However, unusual discoloration can sometimes indicate spoilage, contamination, or toxicity, so it’s best to avoid them if unsure.

Yes, off-color mushrooms can be a sign of spoilage, mold, or toxicity, which can cause illness. If a mushroom looks discolored, slimy, or has an off smell, it’s safer to discard it.

Trust your instincts. If the mushroom smells bad, feels slimy, or has an unnatural color (e.g., bright green, black, or excessive brown spots), it’s likely unsafe. When in doubt, consult a mushroom expert or avoid consuming it.