Peckerhead mushrooms, also known as *Phallus impudicus*, are a type of fungus commonly found in woodland areas across Europe and North America. While their distinctive phallic shape and foul odor make them easily recognizable, many people wonder whether these mushrooms are safe to eat. Despite their unappetizing appearance and smell, peckerhead mushrooms are not considered toxic to humans, but they are generally not recommended for consumption due to their unpleasant taste and texture. Instead, they play a crucial role in forest ecosystems by aiding in decomposition and nutrient cycling. Foraging enthusiasts are advised to avoid consuming them and focus on more palatable and well-documented edible mushroom species.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Common Name | Peckerhead Mushroom |

| Scientific Name | Mutinus caninus |

| Edibility | Not recommended for consumption |

| Reason for Non-Edibility | Lack of culinary value, unpleasant taste, and potential for confusion with toxic species |

| Taste | Unpleasant, often described as foul or bitter |

| Texture | Slimy and unappealing |

| Appearance | Phallic shape, reddish-brown to pinkish cap, slimy outer layer (gleba) |

| Habitat | Found in wooded areas, often near decaying wood or leaf litter |

| Season | Summer to fall |

| Similar Edible Species | None closely resembling Peckerhead Mushroom |

| Potential Risks | Misidentification with toxic mushrooms, gastrointestinal discomfort if consumed |

| Conservation Status | Not evaluated, but generally considered common |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Identifying Peckerhead Mushrooms

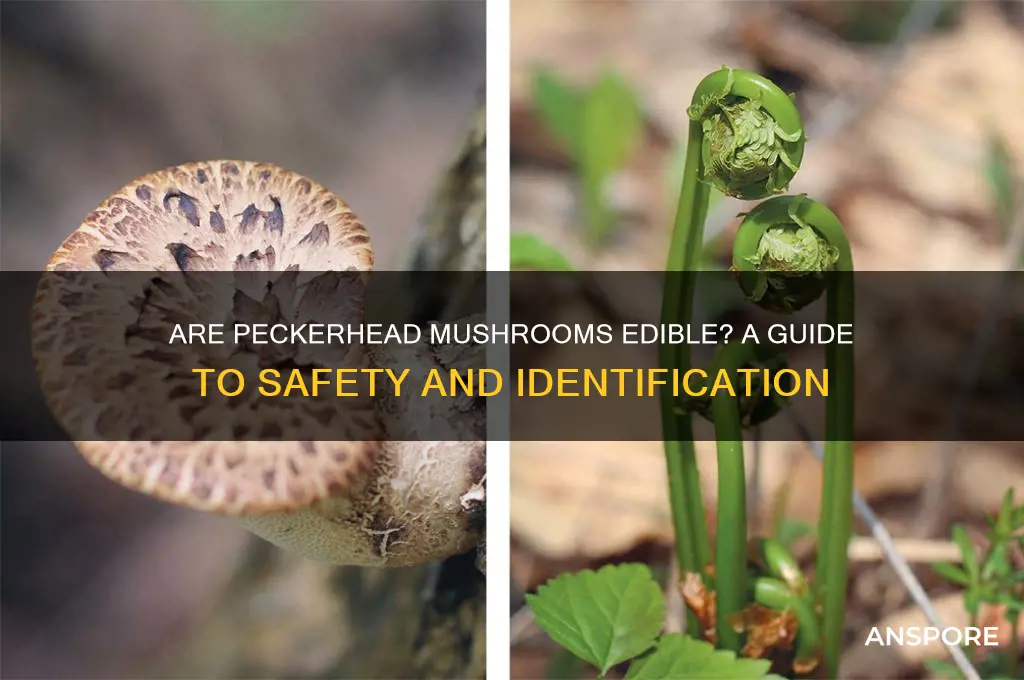

Peckerhead mushrooms, scientifically known as *Mutinus caninus*, are a peculiar sight in the forest, often sparking curiosity due to their distinctive phallic shape. Identifying these mushrooms correctly is crucial, as misidentification can lead to confusion with toxic species. While peckerhead mushrooms are generally considered non-toxic, their edibility is questionable due to their unappealing texture and mild laxative effects. To safely explore their identification, start by examining their unique morphology: a slender, cylindrical cap that tapers to a point, often covered in a greenish-brown spore-bearing slime. This slime, or gleba, is a key feature that distinguishes them from look-alikes.

When venturing into the woods to spot peckerhead mushrooms, focus on their habitat. They thrive in deciduous forests, particularly under oak and beech trees, where they grow singly or in small clusters. Their season typically peaks in late summer to early fall, making this the ideal time for identification. A hand lens can be a valuable tool to observe the fine details, such as the reticulated (net-like) pattern on the stalk, which is a hallmark of this species. Avoid touching the gleba excessively, as it can stain clothing and skin, and always wear gloves if handling them for study.

One common mistake in identifying peckerhead mushrooms is confusing them with *Clathrus archeri*, the octopus stinkhorn, which shares a similar habitat but has a more complex, tentacle-like structure. To differentiate, note that peckerhead mushrooms lack the branching arms and have a smoother, more uniform stalk. Another look-alike is the dog stinkhorn (*Mutinus elegans*), which is slightly larger and has a more pronounced volva at the base. Careful observation of these distinctions ensures accurate identification and reduces the risk of misadventure.

Foraging for peckerhead mushrooms should be approached with caution, as their edibility is not widely endorsed. While some sources suggest they can be consumed in small quantities after thorough cooking, their slimy texture and potential laxative effects make them unappealing. If you choose to experiment, limit consumption to a single mushroom and monitor for adverse reactions. Always consult a mycologist or a reliable field guide before ingesting any wild mushroom. Identification should be the primary goal, as understanding these fungi contributes to a deeper appreciation of their ecological role rather than their culinary value.

In conclusion, identifying peckerhead mushrooms requires attention to detail, from their phallic shape and slimy gleba to their forest habitat and seasonal appearance. Armed with this knowledge, enthusiasts can confidently distinguish them from similar species and contribute to the broader understanding of these fascinating fungi. Whether for academic interest or casual observation, the process of identification is a rewarding endeavor that fosters respect for the natural world.

Are Russula Mushrooms Edible? A Guide to Identification and Safety

You may want to see also

Edibility and Safety Concerns

Peckerhead mushrooms, scientifically known as *Mutinus caninus*, are often mistaken for their more notorious look-alike, the dog stinkhorn (*Mutinus elegans*). While both are part of the Phallaceae family, their edibility and safety profiles differ significantly. Peckerhead mushrooms are generally considered edible when young, but their mature stage renders them unpalatable due to their slimy, spore-covered gleba. Consuming them at this stage may cause gastrointestinal discomfort, though severe toxicity is rare. The key to safe consumption lies in precise timing: harvest only the firm, immature specimens, and avoid those with visible spore masses.

From a comparative perspective, peckerhead mushrooms pale in culinary value when stacked against popular edible varieties like button or shiitake mushrooms. Their fleeting edibility window and lack of robust flavor make them a less appealing choice for most foragers. However, their unique phallic shape and rapid growth cycle have earned them a place in mycological curiosity rather than gourmet cuisine. For those determined to experiment, blanching the immature mushrooms to remove any traces of gleba can mitigate potential irritation, though this step is often more trouble than it’s worth.

Safety concerns extend beyond edibility to proper identification. Misidentification is a significant risk, as peckerhead mushrooms resemble toxic species like the deadly amanitas in their early stages. Novice foragers should avoid harvesting without expert guidance or a reliable field guide. Additionally, the mushrooms’ habitat—often decaying wood or mulch—raises concerns about contamination from pesticides or pollutants. Always source them from clean, undisturbed environments and inspect thoroughly for signs of decay or infestation.

For those considering peckerhead mushrooms as a novelty ingredient, moderation is key. Even when prepared correctly, their consumption should be limited to small quantities due to their laxative properties in some individuals. Children, pregnant women, and those with sensitive digestive systems should avoid them altogether. As with any wild mushroom, cross-contamination during preparation is a risk; use separate utensils and surfaces to prevent spore transfer to other foods. While peckerhead mushrooms may not be a culinary staple, their edibility—when approached with caution—highlights the fascinating diversity of the fungal kingdom.

Are Birch Mushrooms Edible? A Guide to Safe Foraging

You may want to see also

Common Look-Alike Species

Peckerhead mushrooms, scientifically known as *Mycena lux-coeli*, are bioluminescent fungi that often captivate foragers with their ethereal glow. However, their allure can be misleading, as several look-alike species share similar habitats and appearances but pose varying risks. Identifying these doppelgängers is critical, as misidentification can lead to gastrointestinal distress or worse. Below, we dissect the most common imposters and provide actionable guidance for safe foraging.

The Luminous Deceiver: *Mycena chlorophos*

While both *M. lux-coeli* and *M. chlorophos* emit a green glow, their edibility differs. *M. chlorophos* is generally considered non-toxic but lacks culinary value due to its bitter taste and fibrous texture. Distinguishing features include its brighter, almost neon glow and a slightly taller, more slender stipe. Foragers should avoid consumption unless explicitly verifying the species through spore print analysis (typically white for *M. lux-coeli* vs. pale yellow for *M. chlorophos*).

The Toxic Twin: *Galerina marginata*

Often found in similar decaying wood environments, *Galerina marginata* is a deadly look-alike. Its brown cap and slender build can mimic non-luminous peckerhead varieties. The key differentiator is the absence of bioluminescence in *Galerina*. However, in low-light conditions, this distinction may be missed. Always perform a gill inspection: *Galerina* has rusty-brown spores, while peckerheads have white. Ingesting *Galerina* can cause severe liver damage within 6–12 hours, requiring immediate medical attention.

The Edible Confidant: *Panellus stipticus*

This bioluminescent species is occasionally mistaken for peckerheads due to its glowing properties. However, *P. stipticus* grows in fan-like clusters on wood, whereas peckerheads are solitary or in small groups. While *P. stipticus* is non-toxic, it is tough and unpalatable. Foragers should note its orange-brown cap and lack of a distinct stipe, features absent in *Mycena* species.

Practical Tips for Safe Foraging

- Habitat Check: Peckerheads prefer decaying hardwood; verify the substrate before harvesting.

- Glow Test: Crush a small portion of the mushroom; true peckerheads glow brighter when damaged.

- Spore Print: Always collect a spore print overnight to confirm white spores.

- Avoid Dusk Harvesting: Low light increases the risk of confusing bioluminescent species.

In conclusion, while peckerhead mushrooms are edible and safe, their look-alikes demand meticulous scrutiny. Combining habitat knowledge, morphological analysis, and bioluminescent behavior ensures accurate identification, safeguarding both culinary exploration and personal health.

Are Black Mushrooms Edible? A Guide to Safe Foraging and Consumption

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$7.61 $8.95

Culinary Uses and Recipes

Peckerhead mushrooms, also known as *Phallus impudicus*, are not typically considered edible due to their foul odor and unappetizing appearance. However, in the realm of culinary experimentation, even the most unlikely ingredients can find their place. For the daring forager or chef, incorporating peckerhead mushrooms into recipes requires a delicate balance of creativity and caution. While not a staple in traditional cuisine, their unique characteristics can be leveraged in specific, controlled ways.

One unconventional approach is to use the mushroom's potent aroma as a flavor enhancer rather than a primary ingredient. Infusing oils or broths with a small, carefully measured amount of the mushroom can add an earthy, umami depth to dishes. For instance, simmering a single, young peckerhead mushroom in a liter of vegetable broth for 15 minutes can create a base for soups or risottos. Strain the broth thoroughly to remove any remnants, ensuring the final product is both safe and palatable. This method is best suited for experienced cooks who understand the risks and can monitor the process closely.

For those interested in fermentation, peckerhead mushrooms can be an intriguing addition to homemade sauerkrauts or kimchi. Their natural bacteria can contribute to the fermentation process, though this requires precise control to avoid spoilage. Start by finely chopping a small portion of the mushroom (no more than 10 grams per kilogram of vegetables) and mix it with cabbage, salt, and other traditional ingredients. Allow the mixture to ferment for 7–10 days, monitoring daily for off-putting odors or signs of decay. This technique is not for the faint of heart but can yield a uniquely flavored, probiotic-rich dish.

It’s crucial to emphasize that these culinary uses are experimental and come with significant risks. Peckerhead mushrooms are not traditionally consumed, and their edibility remains questionable. Always consult expert sources or mycologists before attempting to cook with them. Foraging should only be done with absolute certainty of identification, as misidentification can lead to severe illness or worse. If you’re curious about incorporating unusual ingredients into your cooking, start with safer, well-documented alternatives before venturing into uncharted territory.

Are Mushroom Edibles Legal? Understanding Psilocybin Laws and Regulations

You may want to see also

Habitat and Growing Conditions

Peckerhead mushrooms, scientifically known as *Mutinus caninus*, thrive in specific environments that cater to their unique life cycle. These fungi are commonly found in deciduous woodlands, where they form symbiotic relationships with trees like oak, beech, and maple. Their preference for rich, organic matter means they often appear in areas with well-rotted wood chips, leaf litter, or compost piles. This habitat provides the necessary nutrients for their growth, particularly during late summer and early autumn when conditions are ideal.

To cultivate peckerhead mushrooms successfully, mimic their natural habitat by creating a moist, shaded environment. Start by preparing a substrate of deciduous wood chips mixed with compost or well-aged manure. Keep the substrate consistently damp but not waterlogged, as excessive moisture can lead to rot. A shaded area with indirect sunlight is ideal, as direct sunlight can dry out the substrate too quickly. Patience is key, as these mushrooms take several weeks to fruit, and their growth is highly dependent on temperature and humidity levels.

While peckerhead mushrooms are edible when young, their habitat and growing conditions play a critical role in their safety for consumption. Avoid harvesting them from areas treated with pesticides or near roadsides, as they can absorb toxins. Instead, focus on pristine woodland environments or controlled cultivation setups. Always inspect the mushrooms for signs of decay or insect damage, as these can indicate spoilage. Proper identification is crucial, as their peculiar shape can sometimes lead to confusion with toxic species.

Comparatively, peckerhead mushrooms differ from other edible fungi in their habitat preferences. Unlike button mushrooms that thrive in controlled, indoor environments, peckerheads require the unpredictability of outdoor ecosystems. Their reliance on deciduous trees and organic debris makes them less suitable for large-scale farming but ideal for foragers and hobbyists. Understanding these nuances ensures not only a successful harvest but also a safe and enjoyable culinary experience.

Exploring Washington's Mushrooms: Are They All Safe to Eat?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Peckerhead mushrooms, also known as *Phallus impudicus*, are not considered edible. They are a type of stinkhorn fungus and are generally avoided due to their foul odor and unappetizing appearance.

While cooking might reduce the odor, peckerhead mushrooms are not recommended for consumption. Their texture and taste are unappealing, and there is no culinary value associated with them.

Peckerhead mushrooms are not typically poisonous, but they are not considered safe to eat. Ingesting them could cause digestive discomfort due to their unpleasant nature.

If you find peckerhead mushrooms, it’s best to leave them alone. They play a role in decomposing organic matter and are not harmful to plants or lawns. Removing them is optional but not necessary.

No, peckerhead mushrooms have a distinct phallic shape and slimy, foul-smelling spore mass that sets them apart from edible mushrooms. Always consult a mycologist or field guide before consuming wild mushrooms.