Pollen and spores are often confused with eggs due to their microscopic size and reproductive roles, but they serve distinct functions in different organisms. Pollen, produced by flowering plants, is a male gametophyte that facilitates fertilization in seed-bearing plants, while spores are reproductive units found in fungi, algae, and non-flowering plants like ferns, used for asexual or sexual reproduction. Eggs, on the other hand, are female reproductive cells present in animals and some plants, requiring fertilization by sperm to develop into offspring. Though all three are involved in reproduction, pollen and spores are not eggs; they belong to separate biological processes and organisms, highlighting the diversity of reproductive strategies in the natural world.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Pollen vs. Spores: Key Differences

Pollen and spores, though often confused, serve distinct roles in the reproductive strategies of plants and fungi. Pollen, produced by seed plants like flowering plants (angiosperms) and conifers (gymnosperms), is a male gametophyte specifically adapted for fertilization. Each pollen grain contains genetic material and is designed to travel—via wind, water, or animals—to reach the female reproductive structure, such as a stigma. Spores, in contrast, are reproductive units produced by plants like ferns, mosses, and fungi. They are not directly involved in fertilization but instead develop into new individuals under favorable conditions. This fundamental difference in function underscores their unique structures and dispersal mechanisms.

Consider the structural disparities: pollen grains are typically larger (20–70 micrometers) and often have intricate, species-specific shapes to aid in attachment and recognition. For instance, ragweed pollen has spiky surfaces, while pine pollen is winged for wind dispersal. Spores, on the other hand, are smaller (5–50 micrometers) and simpler in structure, optimized for survival and dispersal over long distances. Fungal spores, like those of mold, are lightweight and can remain dormant for years until conditions are right for growth. This simplicity allows spores to thrive in diverse environments, from arid deserts to damp forests.

From a practical standpoint, understanding these differences is crucial for allergy sufferers. Pollen allergies, such as hay fever, are triggered by specific pollen types, with grass and ragweed being common culprits. Monitoring pollen counts and using antihistamines (e.g., 10–20 mg of cetirizine daily for adults) can help manage symptoms. Spores, particularly mold spores, are associated with indoor allergies and respiratory issues. Reducing indoor humidity below 50% and using HEPA filters can minimize spore exposure. While both can cause discomfort, identifying the source—pollen or spores—tailors the solution.

A comparative analysis reveals their ecological roles. Pollen is a transient agent of fertilization, dependent on external factors for success. Spores, however, are survivalists, capable of withstanding harsh conditions until they can germinate. For example, fern spores can lie dormant in soil for years, while pollen viability rarely exceeds a few days. This resilience makes spores key players in ecosystem recovery after disturbances like wildfires. Pollen, meanwhile, drives genetic diversity in plant populations through cross-pollination, ensuring adaptability to changing environments.

In summary, while both pollen and spores are reproductive units, their purposes, structures, and impacts differ markedly. Pollen is specialized for fertilization in seed plants, with complex adaptations for dispersal and recognition. Spores are versatile survival structures, enabling fungi and non-seed plants to colonize new areas and endure adversity. Recognizing these distinctions not only clarifies their biological roles but also informs practical applications, from allergy management to ecological restoration.

Identifying Contamination in Spore Jars: Signs, Solutions, and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Are Pollen Grains Considered Eggs?

Pollen grains and eggs serve distinct reproductive roles in plants and animals, respectively, yet their functions often invite comparison. Pollen grains are male gametophytes produced by seed plants, containing sperm cells that fertilize female ovules. Eggs, in contrast, are female reproductive cells in animals, housing genetic material and nutrients for embryonic development. While both are essential for reproduction, their structures, mechanisms, and contexts differ fundamentally. Pollen grains are dispersed externally, often by wind or pollinators, whereas eggs are internally protected within an organism’s body. This distinction highlights why pollen grains are not considered eggs, despite their shared role in perpetuating life.

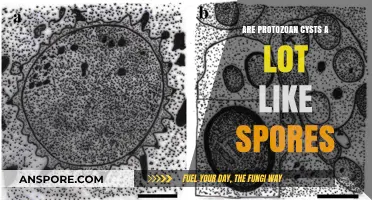

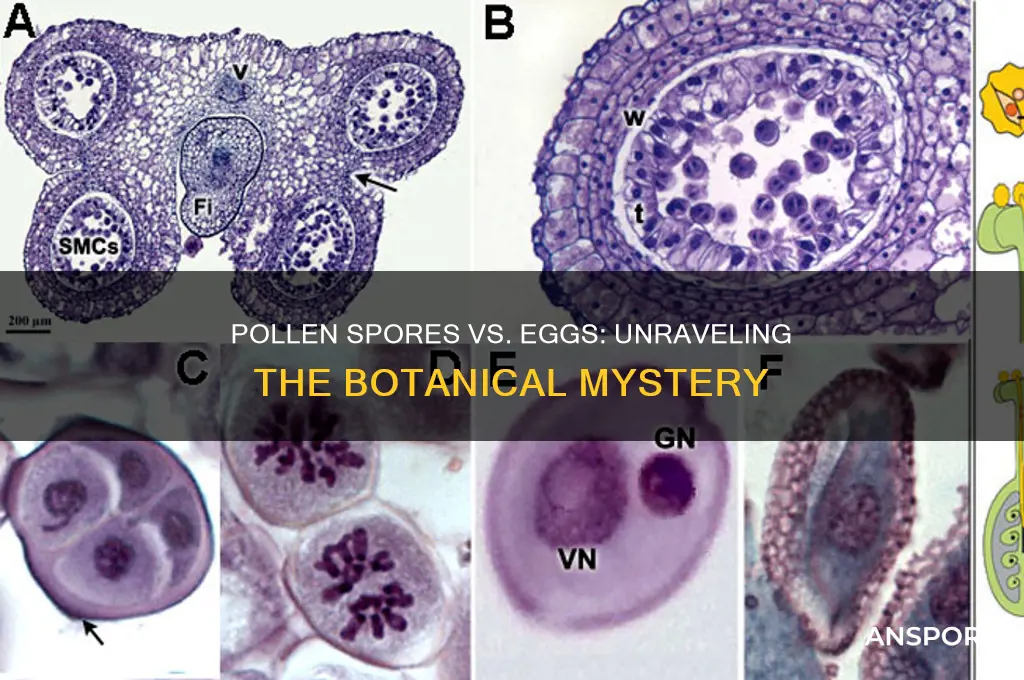

To understand why pollen grains are not classified as eggs, consider their developmental pathways. Pollen grains develop within the anthers of flowers, each containing a generative cell that divides to form two sperm cells. These sperm are delivered to the ovule via pollination, where one fertilizes the egg cell and the other the central cell, forming the embryo and endosperm. Eggs, however, are produced through oogenesis in animals, maturing in ovaries and released during ovulation. They are nutrient-rich, self-contained units designed to support early embryonic growth. Pollen grains, by contrast, rely on the female plant’s tissues for nourishment post-fertilization. This divergence in development underscores their separate identities.

A persuasive argument against equating pollen grains with eggs lies in their evolutionary origins. Eggs evolved in multicellular organisms as a means to protect and nourish developing offspring internally. Pollen grains, on the other hand, emerged in vascular plants as part of an external reproductive strategy, adapted for dispersal and survival in diverse environments. While both structures facilitate fertilization, their adaptations reflect distinct evolutionary pressures. Pollen grains are lightweight, durable, and often coated with protective substances to withstand external conditions, whereas eggs are metabolically active and shielded within the body. These differences reinforce the inapplicability of labeling pollen grains as eggs.

Practically speaking, confusing pollen grains with eggs could lead to misconceptions in biology education or agricultural practices. For instance, farmers and gardeners must understand pollen’s role in plant reproduction to optimize crop yields through pollination management. Mistakenly treating pollen as analogous to eggs might result in misapplied techniques, such as over-relying on external fertilization methods or misunderstanding plant breeding processes. Educators should emphasize the unique characteristics of pollen grains—their structure, function, and ecological role—to clarify their distinction from eggs. This precision ensures accurate knowledge transfer and effective application in real-world scenarios.

In conclusion, while pollen grains and eggs both contribute to reproduction, their differences in structure, development, and evolutionary context preclude classifying pollen grains as eggs. Recognizing these distinctions is crucial for scientific accuracy and practical applications in fields like agriculture and education. By appreciating the unique roles of each, we gain a deeper understanding of the diverse strategies life employs to ensure continuity across species.

Are Mold Spores Carcinogens? Uncovering the Health Risks and Facts

You may want to see also

Role of Pollen in Plant Reproduction

Pollen, often mistaken for spores or eggs, plays a distinct and vital role in plant reproduction. Unlike spores, which are reproductive units capable of growing into new organisms without fertilization, pollen grains are male gametophytes specifically designed to deliver sperm cells to the female reproductive structure of a plant. Similarly, pollen is not an egg; eggs are female reproductive cells found within the ovule of a plant. Pollen’s primary function is to facilitate fertilization, a process essential for the production of seeds and the continuation of plant species.

To understand pollen’s role, consider the steps of pollination and fertilization. First, pollen must be transferred from the male part (anther) of a flower to the female part (stigma). This can occur via wind, water, or animals like bees. Once deposited, the pollen grain germinates, forming a pollen tube that grows down through the style toward the ovary. Inside the pollen tube, sperm cells travel to reach the egg within the ovule. Successful fertilization results in the formation of a zygote, which develops into an embryo, and the ovule matures into a seed. This process highlights pollen’s critical role as the carrier of male genetic material.

Practical tips for optimizing pollen’s role in plant reproduction include ensuring diverse pollinator habitats to enhance pollination rates. For example, planting bee-friendly flowers near crops can increase bee activity, improving pollen transfer. In controlled environments, such as greenhouses, hand-pollination can be employed using a small brush to transfer pollen between flowers. For wind-pollinated plants like corn, spacing plants appropriately ensures pollen dispersal. Additionally, monitoring weather conditions is crucial, as rain or high humidity can hinder pollen viability.

Comparatively, while spores and eggs serve reproductive functions in other organisms, pollen’s specialized role in angiosperms (flowering plants) is unique. Spores, common in ferns and fungi, are asexual and can develop into new individuals without fertilization. Eggs, found in animals and some plants, are female gametes awaiting fertilization. Pollen, however, is a bridge between male and female plant structures, embodying a sophisticated system of sexual reproduction. This distinction underscores the importance of pollen in the diversity and success of flowering plants.

In conclusion, pollen is neither a spore nor an egg but a key player in plant reproduction. Its role in delivering sperm to the egg ensures genetic diversity and the production of seeds. By understanding and supporting pollen’s function through practical measures, gardeners, farmers, and conservationists can enhance plant health and productivity. This knowledge not only clarifies misconceptions but also empowers individuals to actively contribute to the reproductive success of plants.

Do Dead Mold Spores Impact Analysis Results? A Detailed Look

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Spores: Fungal vs. Plant Reproduction

Pollen and spores are often conflated, yet they serve distinct reproductive roles in plants and fungi. While pollen is a male gametophyte in seed plants, essential for fertilization, spores are asexual reproductive units in fungi and non-seed plants like ferns. This fundamental difference in function—sexual versus asexual reproduction—highlights their unique evolutionary strategies. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for fields like botany, mycology, and agriculture, where precise terminology ensures clarity in research and practice.

Fungal spores are marvels of resilience, designed for survival and dispersal. Produced in vast quantities, they can withstand extreme conditions, from arid deserts to freezing tundra. For instance, a single mushroom can release up to 16 billion spores in a day, ensuring widespread propagation. These spores are lightweight and often airborne, allowing them to travel great distances. In contrast, plant spores, such as those from ferns or mosses, are typically larger and require moisture for dispersal and germination. This adaptability in fungal spores underscores their role in colonizing diverse environments, a trait less pronounced in plant spores.

Plant reproduction, particularly in seed plants, relies on pollen as a vector for sexual reproduction. Pollen grains contain the male gametes and are transferred to the female reproductive structure, often via pollinators like bees or wind. This process is highly specialized and energy-intensive, requiring precise timing and environmental conditions. For example, apple orchards depend on cross-pollination, where pollen from one tree fertilizes another, necessitating the planting of compatible varieties within proximity. In contrast, fungal reproduction through spores is asexual and less resource-demanding, enabling rapid colonization without the need for a mate.

The distinction between spores and pollen extends to their ecological roles. Fungal spores contribute significantly to nutrient cycling, breaking down organic matter and returning nutrients to the soil. Plant pollen, meanwhile, is a critical component of ecosystems, supporting pollinators and ensuring genetic diversity in plant populations. For gardeners, understanding these differences can inform practices like companion planting or fungicide application. For instance, avoiding broad-spectrum fungicides during flowering can protect pollinators reliant on pollen while targeting specific fungal pathogens.

In practical terms, distinguishing between spores and pollen has implications for human health and agriculture. Allergies to pollen, such as hay fever, affect millions annually, with symptoms exacerbated by high pollen counts. Monitoring pollen forecasts can help individuals manage exposure, especially during peak seasons like spring. Fungal spores, on the other hand, are linked to respiratory conditions like asthma, particularly in mold-prone environments. Simple measures, such as using dehumidifiers or improving ventilation, can reduce indoor spore levels. By recognizing the unique roles of spores and pollen, individuals can better navigate their environments and mitigate potential health risks.

Effective Ways to Eliminate Mold Spores in Your Home

You may want to see also

Eggs in Plant and Fungal Life Cycles

Pollen and spores are often mistaken for eggs, but their roles in reproduction differ significantly across kingdoms. In plants, pollen grains are male gametophytes that fertilize female ovules, leading to seed formation. These are not eggs but rather carriers of sperm cells. Fungi, on the other hand, produce spores as a means of asexual or sexual reproduction, dispersing to colonize new environments. While neither pollen nor spores are eggs, both are critical reproductive units in their respective life cycles.

In fungal life cycles, eggs—or more accurately, female gametes—are part of the sexual reproduction process in certain species. For example, in basidiomycetes (like mushrooms), the fusion of haploid hyphae forms a dikaryotic mycelium, which eventually produces basidiocarps (fruiting bodies). Within these structures, basidia (specialized cells) undergo meiosis, giving rise to basidiospores. Though not eggs, these spores can germinate and grow into new mycelia. True fungal eggs are rare, but zygomycetes, another fungal group, produce zygospores through the fusion of gametangia, which act as a protective structure for the developing zygote—the closest fungal analog to an egg.

Plants lack eggs in the animal sense but rely on ovules, which contain female gametophytes. After pollination, pollen tubes grow toward the ovule, delivering sperm cells to fertilize the egg cell within the gametophyte. This process, double fertilization, is unique to flowering plants (angiosperms) and results in the formation of a seed. The ovule, not the pollen, houses the egg cell, making it the plant’s counterpart to an egg-bearing structure. Gymnosperms, like conifers, have exposed ovules on cones, while angiosperms enclose them in ovaries.

Comparing plant and fungal reproductive strategies highlights their distinct approaches to survival. Plants invest in seeds, which contain embryos and nutrient stores, ensuring offspring have resources to grow. Fungi, however, prioritize dispersal through spores, which can remain dormant for years until conditions are favorable. While neither uses eggs as animals do, both have evolved specialized structures to protect and propagate their genetic material. Understanding these differences clarifies why pollen and spores are not eggs but are equally vital to their respective life cycles.

For practical insights, gardeners and mycologists can apply this knowledge to optimize growth. Pollination in plants can be enhanced by planting diverse species to attract pollinators or using manual techniques like brushing pollen between flowers. Fungal cultivation benefits from controlling humidity and temperature to encourage spore germination. For example, mushroom growers often use sterile substrates and maintain 60-70% humidity to support mycelium growth. Recognizing the unique roles of pollen, spores, and ovules in reproduction allows for more effective intervention in both plant and fungal ecosystems.

Understanding Mould Spores: How They Spread and Thrive in Your Home

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, pollen spores and eggs are not the same. Pollen spores are male reproductive cells produced by plants, while eggs are female reproductive cells found in animals and some plants.

No, pollen spores do not contain eggs. Pollen is a male gametophyte that produces sperm, which fertilizes the female egg (ovule) in plants.

Yes, both pollen spores and eggs are involved in reproduction, but in different ways. Pollen is part of plant reproduction, while eggs are central to animal and some plant reproductive processes.

No, pollen spores cannot develop into eggs. They are distinct reproductive structures with different functions and origins in plants and animals.