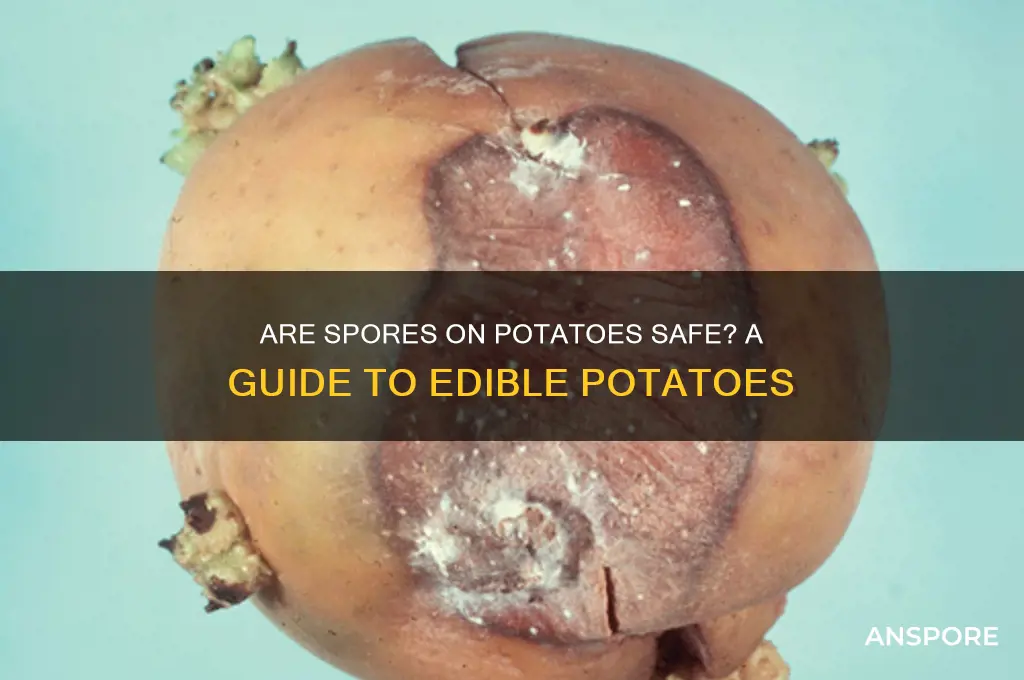

Potatoes with spores, often a sign of mold or fungal growth, raise significant concerns about their safety for consumption. While potatoes are a staple in many diets, the presence of spores can indicate contamination by harmful fungi, such as *Fusarium* or *Penicillium*, which may produce toxic compounds like mycotoxins. Ingesting these toxins can lead to health issues ranging from mild allergic reactions to severe gastrointestinal problems or even long-term health risks. It is generally advised to discard potatoes showing signs of spores, as cutting away the affected area may not eliminate the risk entirely. Understanding the potential dangers and proper handling of spoiled potatoes is crucial for ensuring food safety and preventing illness.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Safety of Potatoes with Spores | Generally unsafe |

| Type of Spores | Usually from mold (e.g., Fusarium, Rhizopus) or bacteria (e.g., Clostridium botulinum) |

| Health Risks | Food poisoning, gastrointestinal issues, potential toxin exposure (e.g., mycotoxins, botulinum toxin) |

| Visible Signs | Mold growth, discoloration, soft spots, unusual odor |

| Prevention | Proper storage (cool, dry, dark place), regular inspection, avoiding damaged potatoes |

| Cooking Effectiveness | Cooking may kill some bacteria but not all toxins (e.g., mycotoxins remain heat-stable) |

| Recommendation | Discard potatoes with visible spores or mold to avoid health risks |

| Alternative | Use fresh, undamaged potatoes for consumption |

| Source of Information | USDA, FDA, and food safety guidelines (as of latest data) |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Identifying spore types on potatoes

Potatoes with spores often raise concerns about safety, but not all spores are created equal. Identifying the type of spore is crucial, as some are harmless while others may indicate spoilage or potential health risks. Here’s how to distinguish between common spore types found on potatoes.

Step 1: Observe the Color and Texture

White or gray spores on potatoes are often associated with mold, such as *Fusarium* or *Rhizopus*. These molds thrive in damp conditions and can produce mycotoxins harmful if ingested. In contrast, black spores may indicate *Alternaria* or *Cladosporium*, which are less toxic but still signal decay. Greenish spores could be *Penicillium*, some strains of which produce toxins. Always discard potatoes with extensive mold growth, especially if the flesh beneath is soft or discolored.

Step 2: Assess the Location and Spread

Spores on the skin often result from environmental factors like soil fungi or storage conditions. If confined to the surface and the potato is firm, peeling and cooking may render it safe. However, spores penetrating the flesh, visible as dark spots or threads, suggest internal decay. For example, *Phoma* spores can cause dry rot, making the potato unsafe even after peeling. When in doubt, err on the side of caution and discard the potato.

Step 3: Consider the Smell and Taste

While not a direct method of spore identification, sensory cues complement visual inspection. Moldy potatoes often emit a musty or sour odor, a red flag for toxin presence. Taste testing is not recommended, as some toxins are undetectable by flavor. For instance, *Fusarium* spores can produce fumonisins, which are odorless and tasteless but harmful in high doses, particularly to children and the elderly.

Practical Tips for Prevention

Store potatoes in a cool, dry place with good ventilation to inhibit spore growth. Avoid washing potatoes before storage, as moisture encourages mold. Regularly inspect stored potatoes and remove any with visible spores to prevent cross-contamination. For households with young children or immunocompromised individuals, adopt a zero-tolerance policy for spores, as their effects can be more severe.

Exploring the Mystery: Are Gas Giants New to Spore's Universe?

You may want to see also

Health risks of consuming spore-infected potatoes

Potatoes infected with spores, particularly those from fungi like *Claviceps purpurea* (ergot) or certain molds, pose significant health risks if consumed. These spores produce mycotoxins, toxic compounds that can cause acute and chronic illnesses. For instance, ergot alkaloids can lead to ergotism, a condition characterized by symptoms ranging from vomiting and diarrhea to more severe effects like gangrene and neurological disorders. Even small amounts of these toxins, such as 1–2 mg of ergot alkaloids per kilogram of body weight, can trigger adverse reactions, particularly in children and the elderly, whose metabolisms are more vulnerable.

Analyzing the risks further, spore-infected potatoes often develop visible signs of contamination, such as mold growth or dark, discolored patches. However, some toxins may be present without obvious symptoms, making it crucial to discard any potato showing abnormalities. Cooking does not always eliminate mycotoxins; for example, aflatoxins produced by *Aspergillus* molds remain stable at temperatures up to 280°C. Thus, relying on heat to neutralize toxins is unreliable, and prevention through careful inspection is paramount.

From a practical standpoint, avoiding spore-infected potatoes involves simple yet effective steps. First, store potatoes in a cool, dry place with good ventilation to prevent moisture buildup, which fosters spore growth. Second, regularly inspect stored potatoes and remove any that show signs of decay or discoloration. Third, wash potatoes thoroughly before use, though this does not guarantee toxin removal. For households with young children or immunocompromised individuals, err on the side of caution and discard any potato with even minor abnormalities.

Comparatively, the risks of consuming spore-infected potatoes outweigh those of other common food safety concerns, such as sprouted potatoes. While sprouted potatoes contain higher levels of glycoalkaloids, which can cause gastrointestinal distress, spore-related toxins are more potent and systemic in their effects. For example, aflatoxin exposure has been linked to liver cancer, particularly in regions where food safety regulations are less stringent. This underscores the need for heightened awareness and proactive measures when handling potentially contaminated produce.

In conclusion, spore-infected potatoes are not safe to eat due to the presence of harmful mycotoxins that can cause severe health issues. By understanding the risks, recognizing signs of contamination, and adopting preventive practices, individuals can protect themselves and their families. While no single method guarantees safety, a combination of vigilant inspection, proper storage, and cautious disposal of suspicious potatoes significantly reduces the likelihood of toxin exposure.

How Do Ferns Reproduce? Unveiling the Mystery of Fern Spores

You may want to see also

Safe cooking methods for spore-contaminated potatoes

Potatoes with spores, often a result of mold growth, pose a significant health risk if consumed without proper handling. The spores, particularly from molds like *Cladosporium* or *Fusarium*, can produce mycotoxins that are harmful even in small quantities. However, not all spore-contaminated potatoes are beyond salvation. Safe cooking methods can mitigate risks, but only if applied correctly and under specific conditions.

Step 1: Assess the Contamination Level

Before attempting to cook spore-contaminated potatoes, evaluate the extent of the damage. Superficial spores on the skin may be manageable, but deep, discolored patches or a soft, mushy texture indicate advanced decay. Discard severely affected potatoes immediately, as toxins can penetrate the flesh and survive cooking. For minor surface spores, proceed with caution, ensuring thorough cleaning and proper cooking techniques.

Step 2: Clean and Peel Strategically

Begin by scrubbing the potatoes under cold running water to remove visible spores. Use a vegetable brush to dislodge particles from the skin. Peeling is non-negotiable; toxins concentrate in the skin and adjacent layers. Discard the peels and any discolored areas. For added safety, trim an additional ¼ inch of flesh beneath the affected surface. This reduces the risk of residual toxins.

Step 3: Apply High-Heat Cooking Methods

High temperatures are effective at neutralizing certain mycotoxins, but not all. Boil, bake, or roast the potatoes at temperatures exceeding 212°F (100°C) for at least 30 minutes. Boiling is particularly effective, as water can leach out soluble toxins. However, avoid frying, as oil temperatures may not reach the required threshold uniformly. Always use a food thermometer to ensure the internal temperature reaches 200°F (93°C).

Cautions and Limitations

While cooking can reduce toxin levels, it does not eliminate all risks. Some mycotoxins, like aflatoxins, are heat-stable and persist even after prolonged cooking. Pregnant individuals, children, and those with compromised immune systems should avoid consuming spore-contaminated potatoes altogether. Additionally, never rely on visual cues alone; toxins are often invisible and odorless.

Practical Tips for Prevention

To minimize future contamination, store potatoes in a cool, dry place with good ventilation. Inspect them regularly and remove any that show signs of spoilage. Avoid washing potatoes before storage, as moisture encourages mold growth. If in doubt, err on the side of caution and discard questionable produce. Safe cooking methods are a last resort, not a guarantee of safety.

Understanding Dangerous Mold Spore Levels: Health Risks and Safety Thresholds

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Common causes of potato spore growth

Potato spore growth, often a concern for both home gardeners and commercial farmers, is primarily caused by fungal pathogens that thrive under specific conditions. One of the most common culprits is *Fusarium* spp., which produces spores that can lead to dry rot. This fungus infiltrates potatoes through wounds or natural openings, particularly when stored in warm, humid environments. For instance, temperatures above 55°F (13°C) and relative humidity exceeding 90% create an ideal breeding ground for these spores. To mitigate this, store potatoes in a cool, dry place with adequate ventilation, ensuring temperatures remain between 45°F and 50°F (7°C and 10°C).

Another significant cause of spore growth is *Rhizoctonia solani*, the fungus responsible for black scurf. This pathogen often persists in soil, infecting potatoes through their skin during growth or harvest. Unlike *Fusarium*, *Rhizoctonia* thrives in cooler, moist soil conditions, making crop rotation and soil management critical preventive measures. Farmers should avoid planting potatoes in the same field consecutively and incorporate organic matter to improve soil drainage. For home gardeners, using disease-resistant potato varieties and sterilizing garden tools can significantly reduce the risk of contamination.

Improper storage practices also contribute to spore growth, particularly in post-harvest scenarios. Potatoes exposed to light develop a green layer containing solanine, a toxic compound, which weakens their skin and makes them more susceptible to fungal spores. To prevent this, store potatoes in dark, paper bags or containers that allow airflow, avoiding plastic bags that trap moisture. Additionally, inspect stored potatoes regularly and remove any that show signs of decay to prevent spores from spreading to healthy tubers.

Lastly, environmental stress during the growing season can weaken potato plants, making them more vulnerable to spore-producing fungi. Drought, nutrient deficiencies, or pest damage compromise the plant’s natural defenses, allowing pathogens to take hold. Farmers and gardeners should maintain consistent soil moisture, apply balanced fertilizers, and monitor for pests to keep plants healthy. For example, applying potassium-rich fertilizers can strengthen cell walls, reducing the likelihood of fungal penetration. By addressing these stressors, the incidence of spore growth can be minimized, ensuring safer and healthier potatoes for consumption.

Understanding Spores: The Silent Killers in The Last of Us

You may want to see also

Preventing spore development on stored potatoes

Potatoes with spores, often a sign of fungal growth, can be a cause for concern. While not all spores are harmful, some can produce toxins that pose health risks. Preventing spore development on stored potatoes is crucial for maintaining their safety and quality. This involves understanding the conditions that foster spore growth and implementing strategies to mitigate them.

Controlling Environmental Factors

Spores thrive in warm, humid environments. To inhibit their development, store potatoes in a cool, dry place with temperatures between 45°F and 50°F (7°C and 10°C) and humidity levels below 85%. Avoid washing potatoes before storage, as moisture accelerates spore growth. Instead, ensure they are completely dry and free of soil, which can harbor fungal spores. Use breathable containers like paper bags or mesh sacks to promote air circulation, reducing the risk of condensation and mold.

Inspecting and Sorting Potatoes

Regularly inspect stored potatoes for signs of spoilage, such as discoloration, soft spots, or visible mold. Immediately remove any affected potatoes to prevent spores from spreading. Sorting potatoes before storage is equally important. Discard those with cuts, bruises, or signs of decay, as these provide entry points for fungal infections. Healthy, intact potatoes are less likely to develop spores, ensuring a safer storage environment.

Chemical and Natural Interventions

For larger-scale storage, consider using approved fungicides or natural remedies to inhibit spore growth. Chloroproham, for instance, is a common chemical treatment applied at a rate of 2–4 ounces per hundredweight of potatoes. Alternatively, essential oils like clove or thyme, known for their antifungal properties, can be used as natural alternatives. Dilute 10–15 drops of essential oil in water and lightly spray the storage area, avoiding direct contact with the potatoes to prevent flavor contamination.

Optimizing Storage Practices

Proper ventilation is key to preventing spore development. Avoid overcrowding potatoes, as this restricts airflow and creates pockets of moisture. Store them in a single layer if possible, or use slatted shelves to allow air to circulate. Additionally, monitor storage conditions regularly, using hygrometers to track humidity and thermometers to ensure consistent temperatures. For long-term storage, consider rotating stock to use older potatoes first, minimizing the risk of prolonged exposure to spore-friendly conditions.

By controlling environmental factors, inspecting and sorting potatoes, using targeted interventions, and optimizing storage practices, you can significantly reduce the likelihood of spore development. These measures not only ensure the safety of stored potatoes but also extend their shelf life, making them safe to eat and reducing food waste.

Meiospores: Understanding Their Sexual or Asexual Nature in Reproduction

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Potatoes with spores are generally not safe to eat. Spores often indicate mold or fungal growth, which can produce toxins harmful to humans.

Spores on potatoes typically appear as fuzzy, powdery, or discolored patches, often white, green, or black, depending on the type of mold or fungus.

Cooking may kill some surface spores, but it does not eliminate toxins produced by mold. It’s best to discard potatoes with visible spores.

Store potatoes in a cool, dry, and well-ventilated place, away from moisture and other produce. Regularly inspect them for signs of spoilage.