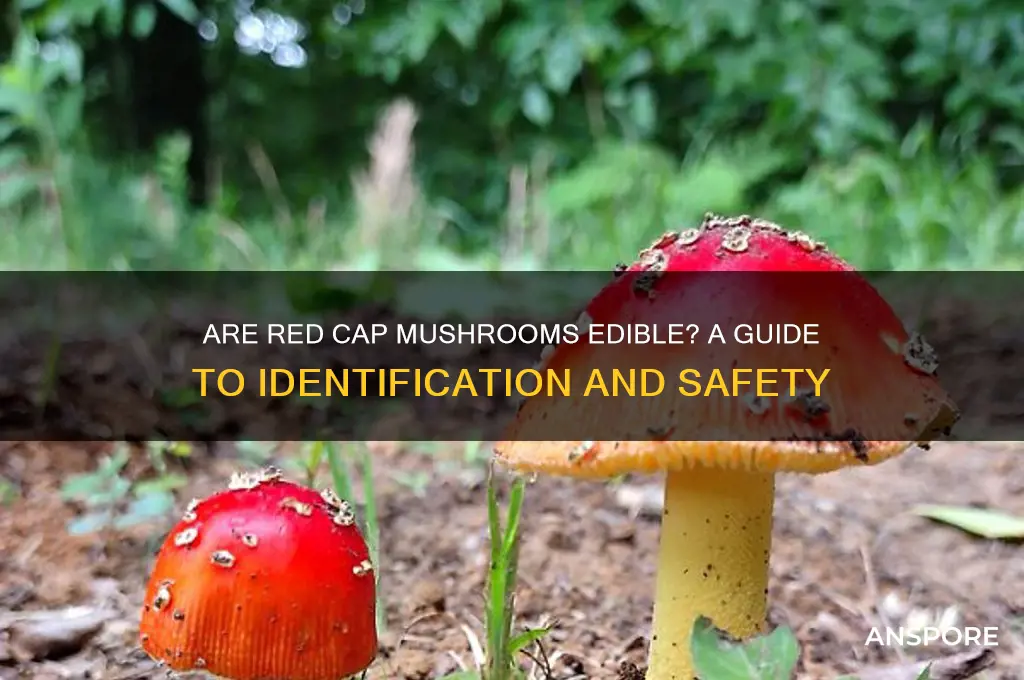

Red cap mushrooms, often striking in appearance with their vibrant red caps, can be both fascinating and potentially dangerous. While some species, like the scarlet elf cup, are indeed edible and even considered a delicacy in certain cultures, many red-capped mushrooms are highly toxic and can cause severe illness or even be fatal if consumed. Identifying these mushrooms accurately is crucial, as their attractive appearance can be misleading. Common toxic varieties include the fly agaric and the deadly amanitas, which bear a resemblance to edible species but contain potent toxins. Therefore, it is essential to consult expert guides or mycologists before foraging or consuming any red cap mushrooms to ensure safety.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Edibility | Generally not edible. Many red-capped mushrooms are poisonous, including the infamous Amanita muscaria (fly agaric) and Amanita regalis (royal fly agaric). |

| Common Species | Amanita muscaria, Amanita regalis, Russula emetica (The Sickener), and some Lactarius species. |

| Toxicity | Can cause severe gastrointestinal symptoms (vomiting, diarrhea), hallucinations, muscle spasms, and in extreme cases, organ failure or death. |

| Key Identifiers | Bright red or reddish cap, often with white spots or warts, white gills, and a bulbous base with a cup-like volva. |

| Safe Red-Capped Mushrooms | Very few exist. Some Lactarius species are edible but require proper identification and preparation. |

| Precaution | Avoid consuming any red-capped mushroom unless positively identified by an expert. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Identifying Red Cap Mushrooms

Red cap mushrooms, with their striking appearance, often catch the eye of foragers and nature enthusiasts. However, not all red-capped fungi are created equal, and misidentification can lead to serious consequences. The key to determining whether a red cap mushroom is edible lies in precise identification, a skill that combines careful observation with knowledge of fungal characteristics.

Color and Texture: Begin by examining the cap’s hue. True red caps range from bright scarlet to deep maroon, but color alone is insufficient for identification. Note the texture: is the cap smooth, sticky, or scaly? For instance, the Fly Agaric (*Amanita muscaria*), a well-known red-capped mushroom, has a vibrant red cap with white flecks and a waxy texture. In contrast, the edible Vermilion Wax Cap (*Hygrocybe miniata*) has a smoother, slimy cap when young. These subtle differences are critical for accurate identification.

Gill and Spore Characteristics: Flip the mushroom over to inspect the gills. Are they white, yellow, or pink? Do they attach directly to the stem or run down it? The Red-Cracked Lachnellula (*Lachnellula araneosa*), for example, has bright red gills that contrast sharply with its darker cap. Additionally, collect spore prints by placing the cap on paper overnight. Edible red caps like the Ruby Waxcap (*Hygrocybe punctata*) typically produce white spores, while toxic varieties may produce different colors.

Habitat and Seasonality: Context matters. Red cap mushrooms often thrive in specific environments. The Scarlet Elf Cup (*Sarcoscypha coccinea*), an edible species, favors decaying wood in moist, shady areas and appears in late winter to early spring. Conversely, the toxic Red-Banded Polypore (*Trichaptum fuscoviolaceum*) grows on dead trees year-round. Knowing when and where a mushroom appears can narrow down possibilities significantly.

Stem and Base Features: Don’t overlook the stem. Is it slender or robust? Does it have a bulbous base or a ring? The edible Orange Peel Fungus (*Aleuria aurantia*), often mistaken for a red cap, has a cup-like structure with no stem. In contrast, the toxic False Chanterelle (*Hygrocybe conica*) has a slender stem and a red-to-orange cap. A magnifying lens can help identify microscopic features like scales or fibers on the stem.

Practical Tips for Safe Foraging: Always cross-reference multiple field guides or apps like iNaturalist for verification. Carry a knife to cut specimens for detailed examination, and avoid touching your face while handling mushrooms. If unsure, consult an expert or mycological society. Remember, no single feature guarantees edibility—only a combination of traits can confirm identity. When in doubt, leave it out.

Mastering the art of identifying red cap mushrooms requires patience and practice, but the reward is a deeper connection to the natural world—and, in some cases, a delicious meal.

Are Puffer Mushrooms Edible? Exploring Safety and Identification Tips

You may want to see also

Toxic Look-Alikes to Avoid

Red-capped mushrooms can be a forager's delight, but their vibrant hue also attracts unsuspecting enthusiasts to toxic imposters. Among the most notorious is the Amanita muscaria, often mistaken for edible red-capped species due to its striking appearance. While not typically fatal, ingestion can lead to severe symptoms like nausea, hallucinations, and muscle spasms. A single cap contains enough ibotenic acid and muscimol to cause discomfort in adults, with effects appearing within 30–90 minutes. Children are particularly vulnerable due to their lower body weight, making proper identification critical.

To avoid confusion, examine the mushroom’s base. Edible red-capped species like the Saffron Milk Cap often have a distinct orange-red latex when cut, while Amanita muscaria lacks this feature. Another toxic look-alike is the Fly Agaric, which shares the same red cap but has white gills and a bulbous base with remnants of a universal veil. Unlike its edible counterparts, it grows in association with coniferous trees, a habitat clue that can save you from a dangerous mistake.

A comparative approach reveals further distinctions. Edible red-capped mushrooms often have a smoother cap and lack the wart-like remnants of a veil found on toxic species. For instance, the Red Chanterelle has a wavy cap and forked gills, whereas the Deadly Galerina mimics its appearance but has brown spores and grows on wood. Always carry a spore print kit to differentiate between the two, as the latter’s rusty brown spores are a red flag.

Instructively, beginners should follow a three-step verification process: habitat, morphology, and spore color. Toxic look-alikes often thrive in specific environments, such as decaying wood or coniferous forests, unlike their edible counterparts. Morphologically, examine the cap’s texture, gill attachment, and stem features. Finally, a spore print can confirm suspicions, as toxic species often produce darker or unusual colors. When in doubt, discard the find—no meal is worth the risk of poisoning.

Persuasively, relying solely on color is a recipe for disaster. The Jack-O-Lantern mushroom, with its bright orange-red cap, is often confused with edible chanterelles but causes severe gastrointestinal distress due to its muscarine toxins. Even experienced foragers fall victim to its deceptive charm. Instead, adopt a skeptical mindset and cross-reference multiple field guides or consult local mycological societies. Remember, the goal is not just to find mushrooms but to ensure they nourish, not harm.

Are Dead Man's Fingers Mushrooms Edible? A Safety Guide

You may want to see also

Edible Red Cap Varieties

Red-capped mushrooms can be a forager's delight, but not all are created equal. Among the myriad of fungi, certain red-capped varieties stand out as both edible and delectable. One such example is the Fly Agaric (*Amanita muscaria*), often mistaken for a purely toxic species. While it is psychoactive and not recommended for culinary use, some cultures parboil it to remove toxins, rendering it edible. However, this process requires expertise and is not advised for novice foragers. Instead, focus on safer, unequivocally edible options like the Red Chanterelle (*Cantharellus cinnabarinus*), a vibrant mushroom prized for its fruity aroma and peppery flavor. Its meaty texture makes it a versatile addition to soups, sauces, and sautéed dishes.

For those seeking a more accessible red-capped mushroom, the Scarlet Elf Cup (*Sarcoscypha coccinea*) is a striking choice. This small, cup-shaped fungus thrives in deciduous woodlands and is often found in winter and early spring. While its flavor is mild, its vivid red color adds a dramatic touch to salads or as a garnish. However, its delicate nature means it’s best enjoyed fresh, as drying can diminish its appeal. Always ensure proper identification, as similar species like the Vermilion Waxcap (*Hygrocybe miniata*) are also edible but require careful distinction from toxic look-alikes.

When foraging for edible red-capped mushrooms, caution is paramount. The Red-Cracked Lachnellula (*Lachnellula araneosa*) is a lesser-known but safe option, often found on decaying wood. Its small size and subtle flavor make it a niche choice, best suited for seasoned foragers. In contrast, the Red-Banded Polypore (*Lentinus lepideus*) is a more robust species, though primarily used for its medicinal properties rather than culinary appeal. Always cross-reference findings with a reliable field guide or consult an expert, as misidentification can have severe consequences.

Practical tips for harvesting edible red-capped mushrooms include using a knife to cut the stem rather than pulling the entire fungus from the ground, which preserves the mycelium. Store fresh mushrooms in paper bags in the refrigerator to maintain their texture and flavor. For long-term storage, drying is recommended, but avoid this method for species like the Scarlet Elf Cup, which lose their appeal when dehydrated. Whether you’re a novice or an experienced forager, focusing on well-documented species like the Red Chanterelle ensures a safe and rewarding culinary adventure.

Are Mock Oyster Mushrooms Edible? A Safe Foraging Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Safe Preparation Methods

Red cap mushrooms, particularly the Amanita muscaria, are often associated with their striking appearance and psychoactive properties, but their edibility is a subject of caution. While some cultures have historically consumed them after careful preparation, they contain toxins that can cause severe gastrointestinal distress if not properly treated. Safe preparation methods are essential to neutralize these toxins and make consumption possible, though it’s crucial to note that even prepared red caps carry risks and are not recommended for casual consumption.

The first step in preparing red cap mushrooms involves thorough cleaning to remove dirt, debris, and surface toxins. Rinse the mushrooms under cold water and gently brush off any stubborn particles. After cleaning, the traditional method of detoxification includes boiling. Place the mushrooms in a pot of water and bring it to a rolling boil for at least 10–15 minutes. This process helps break down the toxins, particularly ibotenic acid and muscimol. Discard the boiling water, as it will contain the leached toxins, and repeat the process once or twice to ensure maximum safety.

Another critical step is drying the mushrooms after boiling. Drying not only preserves them but also further reduces toxin levels. Slice the boiled mushrooms thinly and lay them out in a well-ventilated area away from direct sunlight. Alternatively, use a food dehydrator set at a low temperature (around 50–60°C) for 6–8 hours. Properly dried red caps can be stored for later use, but always rehydrate them in hot water before consumption to ensure any remaining toxins are minimized.

It’s important to approach consumption with extreme caution, even after preparation. Start with a very small dose, such as 1–2 grams of dried mushroom, to assess tolerance. Effects can vary widely depending on individual sensitivity and preparation efficacy. Avoid mixing with alcohol or other substances, and never consume red caps raw or undercooked. Pregnant individuals, children, and those with health conditions should avoid them entirely. While safe preparation methods exist, the risks often outweigh the benefits, making red cap mushrooms a choice best left to experienced foragers and ethnobotanists.

Exploring Edible Mushrooms: A Guide to Safe and Tasty Varieties

You may want to see also

Potential Health Risks

Red cap mushrooms, particularly those belonging to the *Amanita* genus, are notorious for their potential toxicity. While not all red-capped species are deadly, misidentification can lead to severe health consequences. For instance, the *Amanita muscaria* (fly agaric) and *Amanita pantherina* (panther cap) contain psychoactive compounds like muscimol and ibotenic acid, which can cause hallucinations, nausea, and disorientation. Ingesting these mushrooms, even in small amounts, poses risks, especially for children or individuals with pre-existing health conditions. Always consult a mycologist or use a reliable field guide before consuming any wild mushroom.

The symptoms of poisoning from red cap mushrooms can vary widely depending on the species and the amount consumed. Early signs may include gastrointestinal distress—such as vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain—within 30 minutes to 2 hours of ingestion. In severe cases, particularly with *Amanita phalloides* (death cap), liver and kidney failure can occur within 24–48 hours, often leading to death if untreated. Immediate medical attention is crucial if poisoning is suspected, as delayed treatment significantly increases the risk of fatal outcomes.

Children are particularly vulnerable to mushroom poisoning due to their smaller body mass and tendency to explore their surroundings. Even a small bite of a toxic red cap mushroom can cause severe symptoms in a child. Parents and caregivers should educate children about the dangers of consuming wild mushrooms and supervise outdoor activities in areas where mushrooms grow. If a child ingests a suspicious mushroom, contact poison control or seek emergency medical care immediately, bringing a sample of the mushroom for identification if possible.

Foraging for wild mushrooms, including red caps, requires caution and expertise. Even experienced foragers can make mistakes, as some toxic species closely resemble edible varieties. For example, the *Amanita gemmata* (jeweled death cap) can be mistaken for edible *Volvariella* species. To minimize risk, follow these practical tips: avoid consuming any mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identification, cook mushrooms thoroughly (though cooking does not neutralize all toxins), and never eat mushrooms found near polluted areas, as they can accumulate harmful substances. When in doubt, throw it out.

While some red cap mushrooms, like certain *Lactarius* species, are edible and even prized in culinary traditions, the potential for confusion with toxic look-alikes makes them a risky choice for casual foragers. The health risks associated with misidentification far outweigh the benefits of consumption. If you’re interested in incorporating wild mushrooms into your diet, consider joining a local mycological society or taking a foraging class to build your knowledge and skills. Remember, the adage "there are old foragers and bold foragers, but no old, bold foragers" holds true—caution is paramount.

Are Earth Stars Edible? Exploring the Safety of This Unique Mushroom

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Not all red cap mushrooms are edible. Some, like the Amanita muscaria, are toxic and can cause severe symptoms if ingested. Always consult a reliable guide or expert before consuming any wild mushroom.

Identifying edible red cap mushrooms requires careful examination of features like gills, stem, and spore color, as well as habitat. Mistaking a toxic species for an edible one can be dangerous, so it’s best to seek professional guidance.

Yes, some edible red cap mushrooms include the Vermilion Wax Cap (Hygrocybe coccinea) and certain species of Lactarius. However, proper identification is crucial, as many red-capped species are poisonous.