Shelf mushrooms, also known as bracket fungi, are a common sight on trees and decaying wood, but determining whether they are safe to eat can be a complex and potentially risky endeavor. While some species, like the chicken of the woods (*Laetiporus sulphureus*), are prized for their culinary value, others can be toxic or even deadly if consumed. Identifying edible varieties requires expertise, as many shelf mushrooms closely resemble their poisonous counterparts. Factors such as location, tree type, and mushroom characteristics play a crucial role in identification. Without proper knowledge or consultation with a mycologist, foraging for shelf mushrooms can pose serious health risks, making it essential to approach this topic with caution and thorough research.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Edibility | Some shelf mushrooms (e.g., oyster mushrooms) are safe to eat, but many are not. Identification is crucial. |

| Toxicity | Many shelf mushrooms are toxic or poisonous, such as certain species of Pleurotus look-alikes or Omphalotus (Jack-o’-lantern mushrooms). |

| Common Safe Species | Oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus), Lion’s Mane (Hericium erinaceus), and some Lentinula species. |

| Common Toxic Species | Jack-o’-lantern (Omphalotus olearius), False Chanterelles, and some Pleurotus look-alikes. |

| Identification Difficulty | High; many toxic species resemble edible ones, requiring expert knowledge or consultation. |

| Symptoms of Poisoning | Gastrointestinal distress, hallucinations, organ failure (depending on the species ingested). |

| Preparation Safety | Proper cooking is essential for edible species, but cooking does not neutralize toxins in poisonous mushrooms. |

| Foraging Risk | High risk without proper identification; foraging without expertise is strongly discouraged. |

| Commercial Availability | Safe species like oyster mushrooms are widely available in stores, reducing the need for wild foraging. |

| Expert Recommendation | Always consult a mycologist or use a reliable field guide before consuming wild mushrooms. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Identifying edible vs. poisonous mushrooms

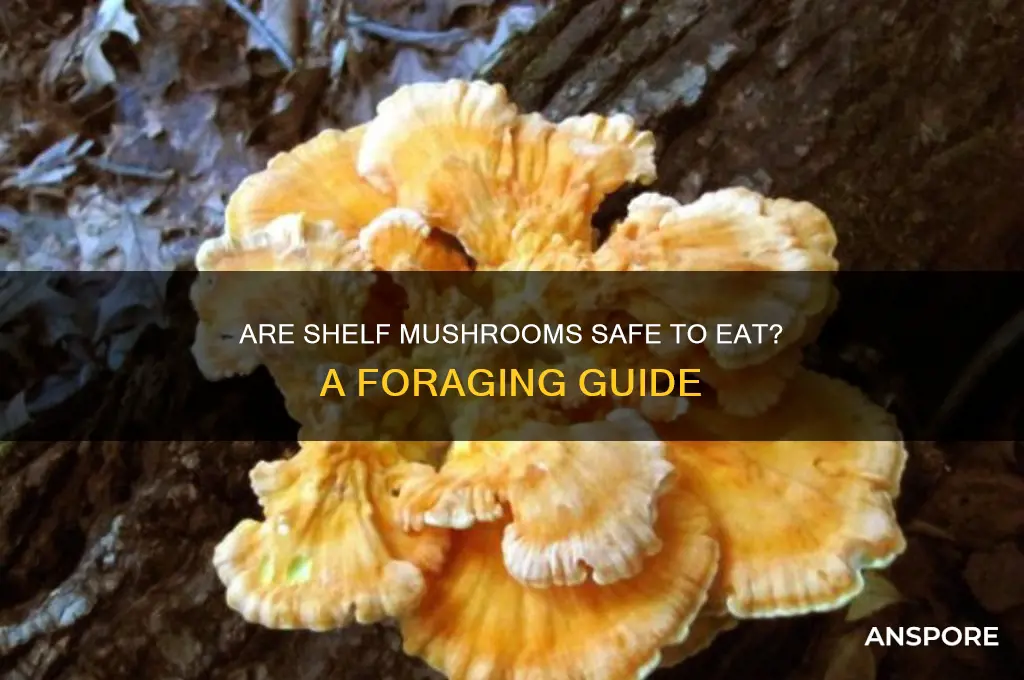

Identifying whether shelf mushrooms are safe to eat requires careful observation and knowledge of key characteristics that distinguish edible species from their poisonous counterparts. Shelf mushrooms, also known as bracket fungi or polypores, grow on trees or wood and often have a tough, woody texture. While some are edible and even prized for their flavor, others can be toxic or cause severe allergic reactions. The first step in identification is to examine the mushroom’s physical features, such as its color, shape, and texture. Edible shelf mushrooms like the Chicken of the Woods (*Laetiporus sulphureus*) typically have bright orange or yellow fan-like structures with a soft, fleshy texture when young. In contrast, poisonous species may have duller colors, a harder texture, or emit an unpleasant odor. Always cross-reference these traits with reliable field guides or expert advice.

Another critical factor in identifying edible vs. poisonous shelf mushrooms is their habitat and the type of wood they grow on. For example, Chicken of the Woods is commonly found on oak, cherry, or eucalyptus trees, while toxic species like the Artist’s Conk (*Ganoderma applanatum*) often grow on deciduous trees and have a varnished, dark brown appearance. Some poisonous mushrooms, such as the toxic *Hapalopilus nidulans*, may resemble edible species but grow on coniferous wood. Observing the tree species and the mushroom’s attachment to the wood (whether it’s a shelf, bracket, or resinous growth) can provide valuable clues. However, relying solely on habitat is not enough; always verify with multiple identifying features.

The underside of the mushroom, where the spores are produced, is another important area to inspect. Edible shelf mushrooms often have pores or tubes on their undersides, while some poisonous species may have gills or a smooth surface. For instance, the edible Sulphur Shelf (*Laetiporus sulphureus*) has bright yellow pores that fade with age, whereas the toxic *Omphalotus olearius* (Jack-O’-Lantern mushroom) has gills and glows in the dark. Additionally, checking for signs of bruising or discoloration when the mushroom is cut or damaged can be helpful. Edible species like the Oyster Mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) typically do not change color when bruised, while some toxic varieties may turn blue or brown.

Taste and smell tests are often discouraged as a primary method of identification because many poisonous mushrooms have no distinct odor or flavor, and some toxic species can even smell pleasant. However, certain edible shelf mushrooms, like the Chicken of the Woods, have a mild, fruity aroma and a taste reminiscent of chicken when cooked. If you are unsure, avoid consuming any mushroom based solely on its smell or a small taste test. Instead, focus on visual and structural characteristics and consult an expert or mycologist for confirmation.

Lastly, it’s essential to understand that regional variations and look-alike species can complicate identification. What is considered edible in one area may be toxic in another due to environmental factors or genetic differences. Always err on the side of caution and avoid consuming any mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity. Joining local mycological societies or foraging groups can provide hands-on learning opportunities and access to experienced foragers who can help you distinguish between edible and poisonous shelf mushrooms safely. Remember, misidentification can have serious health consequences, so thorough research and verification are paramount.

Mushrooms and Diverticulitis: Safe to Eat or Risky Choice?

You may want to see also

Common safe shelf mushroom species

When considering whether shelf mushrooms are safe to eat, it's essential to identify the specific species, as not all shelf mushrooms are edible. Shelf mushrooms, also known as bracket fungi or polypores, grow on trees or wood and have a distinctive shelf-like appearance. Among these, several species are not only safe but also prized for their culinary and medicinal properties. Below are some common safe shelf mushroom species that foragers and enthusiasts can confidently identify and consume.

One of the most well-known edible shelf mushrooms is the Turkey Tail (*Trametes versicolor*). While it is not typically consumed as a culinary mushroom due to its tough texture, it is safe to eat and highly valued for its medicinal properties. Turkey Tail is rich in polysaccharides, particularly beta-glucans, which have been studied for their immune-boosting effects. It is often used in teas or tinctures rather than as a food source. Its vibrant, banded colors make it easy to identify in the wild.

Another safe and edible shelf mushroom is the Oyster Mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*). Although it is not a traditional bracket fungus, it often grows in shelf-like clusters on wood. Oyster mushrooms are highly regarded in culinary circles for their delicate texture and savory flavor. They are easy to identify by their oyster shell-shaped caps and lack of gills (instead, they have pores). These mushrooms are widely cultivated and are a great choice for beginners in foraging.

The Lion's Mane (*Hericium erinaceus*) is a unique and safe shelf mushroom known for its cascading, icicle-like spines. It is highly prized for both its culinary and medicinal uses. Lion's Mane has a texture similar to crab or lobster meat, making it a popular vegetarian substitute in seafood dishes. Additionally, it contains compounds that support nerve health and cognitive function. Its distinctive appearance makes it easy to identify and distinguish from other shelf fungi.

For those interested in medicinal mushrooms, the Reishi (*Ganoderma lucidum*) is a safe and well-known shelf species. While it is too woody to be eaten directly, it is often brewed into teas or extracted into tinctures. Reishi is celebrated for its immune-modulating and stress-relieving properties. Its shiny, kidney-shaped cap and lack of gills make it relatively easy to identify. However, it’s important to note that Reishi should be prepared properly to extract its beneficial compounds.

Lastly, the Chaga (*Inonotus obliquus*) is a safe shelf mushroom that grows primarily on birch trees. It has a unique appearance, resembling a clump of burnt charcoal. Chaga is not consumed directly due to its hard, woody texture but is instead brewed into a tea or extracted. It is rich in antioxidants and has been used traditionally to support overall health and immunity. Proper identification is crucial, as Chaga’s dark, crusty exterior can sometimes be mistaken for other growths.

In summary, while not all shelf mushrooms are safe to eat, species like Turkey Tail, Oyster Mushroom, Lion's Mane, Reishi, and Chaga are well-documented as both safe and beneficial. Proper identification is key, and when in doubt, consulting a field guide or expert is highly recommended. These mushrooms offer a range of culinary and medicinal uses, making them valuable finds for foragers and health enthusiasts alike.

Can You Eat Portobello Mushrooms Raw? Safety and Tips

You may want to see also

Risks of misidentification and toxicity

One of the most significant risks associated with consuming shelf mushrooms, also known as bracket fungi or polypore mushrooms, is the potential for misidentification. Many species of shelf mushrooms grow on trees or wood, and while some are edible and even prized for their culinary uses, others are toxic or inedible. The problem arises because edible and toxic species can often resemble each other closely in appearance. For instance, the Chicken of the Woods (*Laetiporus sulphureus*) is a popular edible shelf mushroom, but it can be confused with the toxic Sulphur Shelf (*Laetiporus conifericola*) or even the extremely poisonous Sulphur Tuft (*Hypholoma fasciculare*). Without proper knowledge and experience, it is easy to mistake one for another, leading to severe health risks.

Misidentification is further complicated by the fact that environmental factors can alter the appearance of mushrooms. Factors such as humidity, temperature, and substrate can cause variations in color, texture, and size within the same species, making identification even more challenging. Additionally, some toxic mushrooms may lack obvious warning signs, such as a bitter taste or unpleasant odor, which are often relied upon as indicators of toxicity. This lack of clear markers increases the likelihood of accidental ingestion of poisonous species, especially for novice foragers.

Toxicity in shelf mushrooms can range from mild gastrointestinal discomfort to severe, life-threatening reactions. For example, the Jack-O-Lantern mushroom (*Omphalotus olearius*) is a toxic look-alike of the edible Chantrelle (*Cantharellus cibarius*). Consuming the Jack-O-Lantern can cause severe vomiting, diarrhea, and dehydration due to its toxic compounds. In more extreme cases, certain toxic shelf mushrooms contain compounds that can cause liver or kidney damage, such as the toxins found in the Funeral Bell (*Galerina marginata*), which resembles some edible brown-capped polypore mushrooms. These toxins can lead to organ failure if not treated promptly.

Another risk is the cumulative effect of toxins in the body. Some toxic mushrooms may not cause immediate symptoms, but repeated exposure or consumption of even small amounts can lead to long-term health issues. This is particularly dangerous for individuals who forage regularly without proper identification skills. Moreover, cooking does not always neutralize toxins in poisonous mushrooms, contrary to popular belief. Some toxins remain active even after boiling or frying, making it crucial to avoid consumption altogether if there is any doubt about a mushroom's identity.

To mitigate the risks of misidentification and toxicity, it is essential to follow strict guidelines when foraging for shelf mushrooms. Always consult reliable field guides, use spore print analysis, and seek guidance from experienced mycologists or local foraging groups. Never consume a mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity. Additionally, avoid foraging in areas contaminated by pollutants, as mushrooms can absorb toxins from their environment, further complicating their safety. The risks of misidentification and toxicity are real and should not be underestimated, as the consequences can be severe or even fatal.

Do Dogs Eat Wild Mushrooms? Risks, Safety, and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$5.49 $6.49

Proper harvesting and preparation methods

When harvesting shelf mushrooms, it’s crucial to identify the species accurately, as not all shelf mushrooms are safe to eat. Only harvest mushrooms that have been positively identified as edible, such as certain species of oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) or lion's mane mushrooms (*Hericium erinaceus*). Avoid mushrooms with any signs of decay, mold, or insect damage. Always use a sharp knife or scissors to cut the mushroom at the base of the stem, leaving the growth point intact to allow for future fruiting. Never pull or uproot the mushroom, as this can damage the mycelium and the surrounding ecosystem. Harvest only what you need and leave some behind to ensure the sustainability of the mushroom population.

After harvesting, proper cleaning is essential to remove dirt, debris, and potential contaminants. Gently brush off loose soil with a soft brush or a clean cloth. Avoid washing the mushrooms with water unless absolutely necessary, as excess moisture can accelerate spoilage. If washing is required, quickly rinse them under cold water and pat them dry with paper towels or a clean kitchen towel. Trim any tough or woody parts of the stem, as these can be fibrous and unpleasant to eat. For shelf mushrooms like oysters, the stems are often tender and can be left intact, but always assess their texture before cooking.

Preparing shelf mushrooms for cooking involves slicing or tearing them into appropriate sizes based on the recipe. Oyster mushrooms, for example, can be torn into bite-sized pieces to maintain their delicate texture. Lion's mane mushrooms are often sliced or shredded to mimic crab or lobster meat in dishes. Regardless of the species, it’s important to cook shelf mushrooms thoroughly to neutralize any potential toxins and improve digestibility. Sautéing, stir-frying, or baking are excellent methods to enhance their flavor and texture. Avoid eating shelf mushrooms raw, as some species can cause digestive upset when not cooked.

To preserve shelf mushrooms for later use, drying is one of the most effective methods. Clean the mushrooms thoroughly and slice them thinly to ensure even drying. Use a dehydrator set at a low temperature (around 125°F or 52°C) or place them on a baking sheet in an oven with the door slightly ajar at the lowest setting. Once completely dry, store the mushrooms in an airtight container in a cool, dark place. Dried mushrooms can be rehydrated in warm water or added directly to soups, stews, and sauces. Freezing is another option; blanch the mushrooms briefly in boiling water, cool them in ice water, drain, and store in airtight bags or containers in the freezer.

Finally, when preparing shelf mushrooms, always prioritize food safety. Cook mushrooms within a day or two of harvesting to ensure freshness. If storing them before cooking, keep them in a breathable container like a paper bag in the refrigerator to maintain their quality. Be cautious of any allergic reactions when trying a new mushroom species, and start with a small portion to test tolerance. By following these proper harvesting and preparation methods, you can safely enjoy the unique flavors and nutritional benefits of edible shelf mushrooms.

Delicious Pairings: Perfect Side Dishes for Stuffed Mushrooms

You may want to see also

Symptoms of mushroom poisoning to watch for

Mushroom poisoning can occur when someone consumes toxic or poisonous mushrooms, and the symptoms can vary widely depending on the type of mushroom ingested. While some shelf mushrooms, also known as bracket fungi, are safe to eat, others can be highly toxic. It’s crucial to accurately identify mushrooms before consumption, as misidentification can lead to severe health risks. If you suspect mushroom poisoning, recognizing the symptoms early is essential for prompt treatment. Symptoms typically appear within 6 to 24 hours after ingestion, though some toxins may cause delayed reactions.

Gastrointestinal symptoms are among the most common signs of mushroom poisoning. These include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and cramping. Such symptoms often occur with mushrooms containing toxins like amatoxins or orellanine. Amatoxins, found in certain species like the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*), can cause severe liver damage, while orellanine, present in some bracket fungi, targets the kidneys. Persistent or severe gastrointestinal distress should never be ignored, as it may indicate a serious poisoning event.

Neurological symptoms are another red flag to watch for. These can include dizziness, confusion, hallucinations, muscle spasms, or seizures. Mushrooms containing psychoactive compounds like psilocybin or toxins like ibotenic acid can cause these effects. While some individuals may seek out psychoactive mushrooms for recreational use, accidental ingestion of toxic species can lead to dangerous and unpredictable neurological reactions. If someone exhibits altered mental states or uncontrolled movements after consuming mushrooms, seek medical attention immediately.

Cardiovascular and respiratory symptoms may also arise in cases of mushroom poisoning. These include rapid heartbeat, low blood pressure, difficulty breathing, or even respiratory failure. Toxins like muscarine, found in certain *Clitocybe* and *Inocybe* species, can cause these symptoms by affecting the nervous system. Such reactions can be life-threatening, especially in vulnerable populations like children, the elderly, or individuals with pre-existing health conditions.

Delayed symptoms are particularly dangerous because they may provide a false sense of security after consuming mushrooms. For example, toxins like amatoxins can cause an initial bout of gastrointestinal symptoms, followed by a seemingly symptom-free period of 24 to 48 hours. However, this is often followed by severe liver and kidney failure, which can be fatal without immediate medical intervention. Similarly, orellanine poisoning may not show symptoms for several days, but it can lead to irreversible kidney damage.

In conclusion, if you or someone you know has consumed mushrooms and experiences any of these symptoms, seek medical help immediately. Bring a sample of the mushroom or a detailed description to aid identification. Remember, when it comes to wild mushrooms, including shelf mushrooms, it’s better to err on the side of caution. Proper identification by an expert is essential to avoid the potentially severe consequences of mushroom poisoning.

A Beginner's Guide to Safely Consuming Magic Mushrooms

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all shelf mushrooms are safe to eat. Some species are toxic or poisonous, and misidentification can lead to severe illness or even death. Always consult a mycologist or use a reliable field guide before consuming wild mushrooms.

Identifying edible shelf mushrooms requires knowledge of specific characteristics such as color, texture, spore print, and habitat. Common edible species include oyster mushrooms and lion’s mane, but always verify with an expert or guide to avoid confusion with toxic look-alikes.

Eating shelf mushrooms from your backyard is risky unless you are absolutely certain of their identification. Factors like pollution, pesticides, or proximity to toxic plants can also make them unsafe. It’s best to avoid consuming wild mushrooms without proper expertise.

Yes, store-bought shelf mushrooms, such as oyster or shiitake mushrooms, are safe to eat as they are cultivated and inspected for quality. However, always check for signs of spoilage, such as mold or an off smell, before consuming.