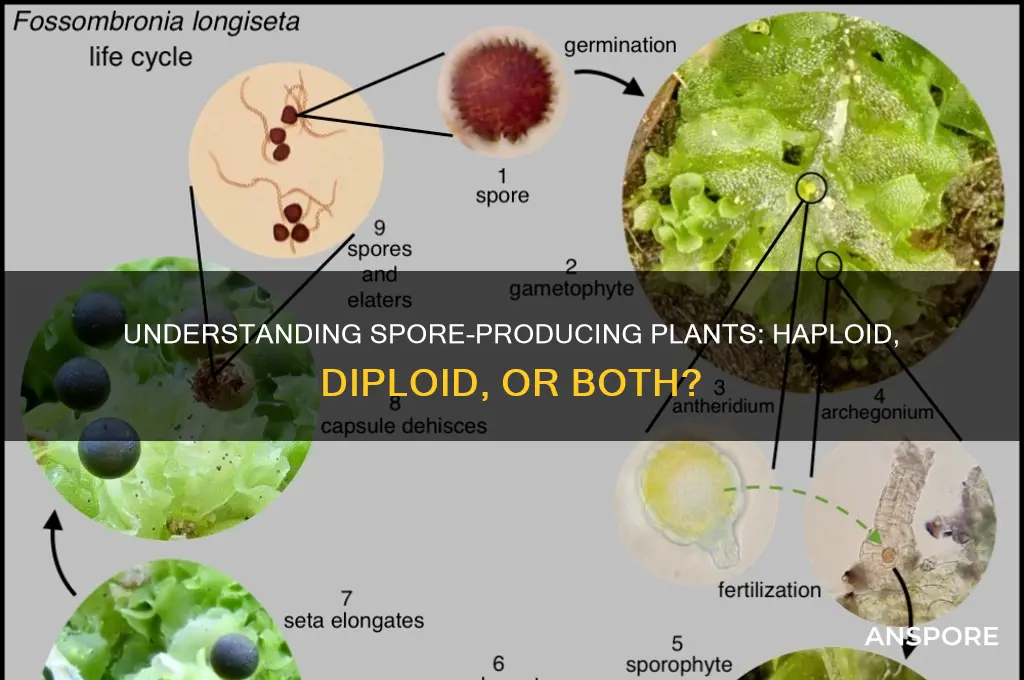

The question of whether spore-producing organisms, such as plants and fungi, are haploid or diploid in their sporophyte phase is a fundamental concept in biology. In the life cycles of these organisms, the sporophyte generation is typically the diploid phase, where cells contain two sets of chromosomes, and it is responsible for producing spores through meiosis. These spores then develop into the haploid gametophyte generation, which carries a single set of chromosomes. Understanding the ploidy of sporophytes is crucial for comprehending the alternation of generations in plants and fungi, as it highlights the intricate balance between haploid and diploid stages in their life cycles. This knowledge is essential for various fields, including botany, mycology, and evolutionary biology, as it provides insights into the reproductive strategies and diversity of these organisms.

Explore related products

$13.99 $17.99

What You'll Learn

- Spore Types: Haploid spores vs. diploid sporangiospores in plant life cycles

- Sporophyte Dominance: Diploid generation predominance in vascular plants

- Gametophyte Role: Haploid phase in bryophytes and ferns

- Alternation of Generations: Haploid-diploid cycles in plant reproduction

- Spore Dispersal: Mechanisms for spreading haploid spores in environments

Spore Types: Haploid spores vs. diploid sporangiospores in plant life cycles

In the intricate dance of plant reproduction, spores play a pivotal role, yet not all spores are created equal. Haploid spores and diploid sporangiospores represent two distinct players in the life cycles of plants, each with unique functions and implications for genetic diversity. Haploid spores, produced by meiosis, carry a single set of chromosomes and are typically associated with the gametophyte generation in alternation of generations. These spores germinate into gametophytes, which produce gametes (sperm and eggs) for sexual reproduction. In contrast, diploid sporangiospores, found in certain fungi and some plants, are formed from mitosis and retain the full set of chromosomes. This fundamental difference in ploidy level drives variations in growth, development, and evolutionary strategies across species.

Consider the life cycle of ferns as an example to illustrate the role of haploid spores. When a fern releases its spores, each spore is haploid and develops into a small, heart-shaped gametophyte (prothallus) upon landing in a suitable environment. This gametophyte is entirely independent, producing both sperm and eggs. Fertilization occurs when sperm swim to an egg, resulting in a diploid sporophyte, which grows into the familiar fern plant. Here, the haploid phase is short-lived but critical, ensuring genetic recombination and adaptability. In contrast, diploid sporangiospores, as seen in some fungi like Zygomycota, bypass the haploid stage, allowing for rapid vegetative growth and asexual reproduction, which can be advantageous in stable environments.

From an evolutionary standpoint, the distinction between haploid spores and diploid sporangiospores highlights the trade-offs between genetic diversity and reproductive efficiency. Haploid spores promote genetic shuffling through meiosis and sexual reproduction, enhancing a species’ ability to adapt to changing environments. Diploid sporangiospores, however, prioritize clonal reproduction, which can quickly colonize favorable habitats but limits genetic variation. For gardeners or ecologists, understanding these differences can inform strategies for plant propagation or conservation. For instance, cultivating ferns from spores requires creating humid conditions to support gametophyte growth, while managing fungal populations might involve disrupting asexual spore dispersal to prevent overgrowth.

Practical applications of this knowledge extend to agriculture and biotechnology. In crop plants like maize, the alternation between haploid and diploid phases is exploited in breeding programs to produce hybrid seeds with desirable traits. Conversely, controlling diploid spore production in pathogenic fungi can mitigate crop diseases. For hobbyists, recognizing whether a plant reproduces via haploid spores or diploid sporangiospores can guide care practices. For example, mosses, which rely on haploid spores, thrive in moist, shaded environments, while molds, often producing diploid spores, require dryness to inhibit growth. This nuanced understanding transforms spore types from abstract concepts into actionable insights for plant care and management.

In conclusion, the dichotomy between haploid spores and diploid sporangiospores underscores the diversity of reproductive strategies in the plant kingdom. While haploid spores drive genetic innovation through sexual reproduction, diploid sporangiospores prioritize rapid proliferation and stability. By recognizing these differences, individuals can tailor their approaches to gardening, conservation, or research, leveraging the unique strengths of each spore type. Whether nurturing a fern from a spore or combating fungal infestations, this knowledge bridges the gap between theoretical biology and practical application, enriching our interaction with the natural world.

How Long Can Mold Spores Survive Without Moisture?

You may want to see also

Sporophyte Dominance: Diploid generation predominance in vascular plants

In vascular plants, the sporophyte generation—the diploid phase—is not just a stage but the dominant, long-lasting form. This contrasts sharply with non-vascular plants like mosses, where the haploid gametophyte reigns supreme. For instance, in a fern, the large, leafy structure we commonly recognize is the sporophyte, while the gametophyte is a tiny, transient heart-shaped structure often hidden from view. This dominance is a key evolutionary adaptation, enabling vascular plants to thrive in diverse environments by leveraging the stability of a diploid genome.

To understand sporophyte dominance, consider the lifecycle of a pine tree. The tree itself is the sporophyte, producing cones that release spores. These spores develop into microscopic gametophytes, which are entirely dependent on the sporophyte for survival. The male gametophyte (pollen grain) requires wind for dispersal, while the female gametophyte remains within the cone. This dependency underscores the sporophyte’s central role in resource allocation and environmental interaction, ensuring the diploid phase drives the plant’s growth and reproduction.

From an evolutionary perspective, sporophyte dominance is a strategic shift. Diploid organisms have two sets of chromosomes, providing genetic redundancy that buffers against harmful mutations. This stability is particularly advantageous in vascular plants, which often live for decades or centuries. For example, a redwood tree’s longevity—up to 2,000 years—relies on the robustness of its diploid genome. In contrast, the haploid gametophyte phase is short-lived, serving solely to produce gametes and bridge generations.

Practical implications of sporophyte dominance are evident in agriculture and horticulture. Crop plants like wheat, rice, and corn are cultivated for their sporophyte tissues—seeds, leaves, or stems. Breeders focus on diploid traits such as yield, disease resistance, and drought tolerance, as these directly impact productivity. Understanding this dominance allows scientists to manipulate plant lifecycles, such as through tissue culture, where sporophyte cells are propagated asexually to preserve desirable traits.

In conclusion, sporophyte dominance in vascular plants is a masterclass in evolutionary efficiency. By prioritizing the diploid generation, these plants achieve stability, longevity, and adaptability. Whether in the towering redwoods or the grains of wheat, this dominance shapes the plant kingdom’s success. Recognizing this principle not only deepens our understanding of botany but also informs practical applications in agriculture and conservation.

Are C. Botulinum Spores Harmful to Human Health?

You may want to see also

Gametophyte Role: Haploid phase in bryophytes and ferns

In the life cycles of bryophytes and ferns, the gametophyte phase is not just a fleeting stage but a dominant and independent entity. Unlike in seed plants, where the gametophyte is reduced to a few cells, bryophytes and ferns exhibit a haploid gametophyte that is free-living and photosynthetic. This phase is critical for the survival and reproduction of these plants, as it directly engages with the environment, absorbing water and nutrients while producing gametes. For instance, in mosses, the gametophyte forms the lush green carpets we often see in forests, while in ferns, it appears as a small, heart-shaped structure known as a prothallus.

Consider the practical implications of this dominance. For gardeners or botanists cultivating ferns, understanding the gametophyte’s role is essential. The prothallus, though small, requires specific conditions—moisture and shade—to thrive. Without these, fertilization cannot occur, halting the life cycle. Similarly, in bryophytes, the gametophyte’s ability to colonize bare soil or rock surfaces makes it a pioneer species in ecological succession. This highlights its ecological significance beyond mere reproduction, serving as a stabilizer for fragile environments.

From an analytical perspective, the haploid nature of the gametophyte in bryophytes and ferns offers evolutionary insights. Haploidy increases genetic diversity through recombination during meiosis and fertilization, a key advantage in adapting to changing environments. For example, mosses can rapidly evolve to tolerate pollution or drought, thanks to this genetic flexibility. In contrast, the diploid sporophyte phase, though dependent on the gametophyte, is less genetically diverse and serves primarily to disperse spores. This division of labor between phases underscores the gametophyte’s central role in both survival and evolution.

To illustrate, let’s compare the gametophytes of a liverwort (Marchantia) and a fern (Pteris). In Marchantia, the gametophyte is a flat, ribbon-like thallus that produces gemmae—asexual reproductive structures—in addition to gametes. This dual function showcases the gametophyte’s versatility. In Pteris, the prothallus is ephemeral but crucial, as it must be present for the sporophyte to develop. These examples emphasize the gametophyte’s adaptability and resilience, traits that have allowed bryophytes and ferns to persist for millions of years.

In conclusion, the gametophyte phase in bryophytes and ferns is a masterclass in efficiency and adaptability. Its haploid nature fosters genetic diversity, while its independence ensures survival in diverse habitats. Whether you’re a botanist, gardener, or ecologist, recognizing the gametophyte’s role is key to appreciating these plants’ unique life cycles. By focusing on this phase, we gain not only scientific insight but also practical knowledge for conservation and cultivation.

Does Bleach Kill Mold Spores? Uncovering the Truth Behind the Myth

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Alternation of Generations: Haploid-diploid cycles in plant reproduction

Plants exhibit a unique reproductive strategy known as alternation of generations, a cycle that seamlessly transitions between haploid and diploid phases. This process is fundamental to understanding plant life cycles, particularly in spore-producing plants like ferns, mosses, and gymnosperms. Unlike animals, where the diploid phase dominates, plants alternate between a haploid gametophyte and a diploid sporophyte generation. Each phase is distinct in structure, function, and genetic composition, yet they are interconnected, ensuring the continuity of the species.

Consider the lifecycle of a fern as a practical example. It begins with a haploid spore, which germinates into a gametophyte (prothallus). This small, heart-shaped structure is often overlooked but plays a critical role. The prothallus produces gametes—sperm and eggs—through mitosis. When fertilization occurs, typically in the presence of water, a diploid zygote forms, developing into the sporophyte, the familiar fern plant we recognize. This mature sporophyte then produces spores via meiosis, completing the cycle. The alternation ensures genetic diversity, as meiosis shuffles genetic material, and the haploid phase allows for rapid adaptation to environmental changes.

From an analytical perspective, the haploid-diploid cycle is a balancing act between stability and adaptability. The diploid sporophyte phase provides robustness, enabling plants to grow larger and more complex structures. In contrast, the haploid gametophyte phase is more vulnerable but offers flexibility. For instance, in mosses, the gametophyte is the dominant phase, thriving in diverse environments due to its simplicity. This duality highlights the evolutionary advantage of alternation of generations, allowing plants to exploit different ecological niches effectively.

For gardeners or botanists, understanding this cycle is crucial for propagation and conservation. For example, to cultivate ferns from spores, one must mimic the conditions required for gametophyte development, such as maintaining high humidity and using sterile soil. Similarly, in seed-producing plants like angiosperms, the haploid phase is reduced to the pollen and embryo sac, but the principles remain the same. By recognizing these phases, one can optimize growth conditions and ensure successful reproduction, whether in a home garden or a botanical research setting.

In conclusion, the alternation of generations is a testament to the ingenuity of plant evolution. It combines the stability of diploidy with the adaptability of haploidy, creating a resilient reproductive strategy. By studying this cycle, we gain insights into plant diversity and develop practical applications for horticulture and conservation. Whether you’re a scientist, gardener, or enthusiast, appreciating this intricate dance between phases deepens our connection to the natural world.

Mastering Fern Propagation: A Step-by-Step Guide to Growing Ferns from Spores

You may want to see also

Spore Dispersal: Mechanisms for spreading haploid spores in environments

Spores, the microscopic units of life, are nature's ingenious solution for survival and propagation in diverse environments. Among these, haploid spores—produced by sporophytes in the life cycle of plants like ferns, fungi, and some algae—are particularly fascinating due to their dispersal mechanisms. These mechanisms ensure that spores travel far and wide, increasing the chances of colonization in new habitats. Understanding these strategies not only sheds light on evolutionary adaptations but also offers insights for applications in agriculture, conservation, and biotechnology.

One of the most common methods of spore dispersal is wind-driven dissemination, a passive yet highly effective technique. Plants like ferns and fungi release lightweight spores that can be carried over vast distances by air currents. For instance, a single fern sporophyte can release millions of spores, each weighing mere micrograms, allowing them to float for kilometers. This mechanism is particularly advantageous in open environments where wind is consistent. However, reliance on wind alone can be unpredictable, making it crucial for plants to produce spores in staggering quantities to ensure at least a fraction land in suitable conditions.

In contrast, water dispersal is a favored method for aquatic or semi-aquatic organisms like certain algae and fungi. Spores released into water currents can travel along rivers, streams, or even ocean tides, reaching distant ecosystems. For example, the spores of *Chara*, a genus of aquatic algae, are often carried by water flow, enabling them to colonize new freshwater habitats. This method is highly efficient in wet environments but limited by the availability and direction of water flow. Combining water and wind dispersal, some spores are designed to be hydrophobic, allowing them to float on water surfaces until wind takes over, showcasing nature's ingenuity in maximizing dispersal range.

Another intriguing mechanism is animal-mediated dispersal, where spores hitch a ride on animals, insects, or even humans. Fungi like *Puccinia* (rust fungi) produce sticky spores that adhere to the bodies of passing insects, ensuring transport to new locations. Similarly, the spores of certain lichens can attach to animal fur or bird feathers, facilitating long-distance travel. This method is particularly effective in dense ecosystems where wind or water dispersal is hindered. For practical applications, understanding this mechanism can inspire the development of bioadhesives or targeted seed dispersal techniques in reforestation efforts.

Finally, explosive mechanisms highlight the active role some plants play in spore dispersal. Capsular structures in fungi, such as the puffball (*Calvatia*), release spores in a cloud when disturbed, either by rain, animals, or human touch. This sudden release ensures rapid and widespread dispersal, often over several meters. Similarly, the "gun mechanism" in *Pilobolus*, a fungus that grows on herbivore dung, launches spores with force, aiming toward light sources to escape the dung environment. These active methods demonstrate how organisms adapt to specific challenges, ensuring survival in competitive ecosystems.

In conclusion, the mechanisms of spore dispersal—wind, water, animals, and explosive release—are tailored to the unique needs of each organism and its environment. By studying these strategies, we gain not only a deeper appreciation for nature's complexity but also practical tools for addressing challenges in agriculture, conservation, and beyond. Whether through passive drift or active propulsion, haploid spores exemplify the resilience and ingenuity of life's smallest units.

Are Milky Spores Pet-Safe? A Comprehensive Guide for Pet Owners

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores produced by sporophytes are haploid.

The sporophyte generation is diploid, as it results from the fusion of two haploid gametes.

No, sporophytes produce haploid spores through meiosis, not diploid spores.

The spores that develop into gametophytes are haploid.

The sporophyte generation is diploid, while the gametophyte generation is haploid.