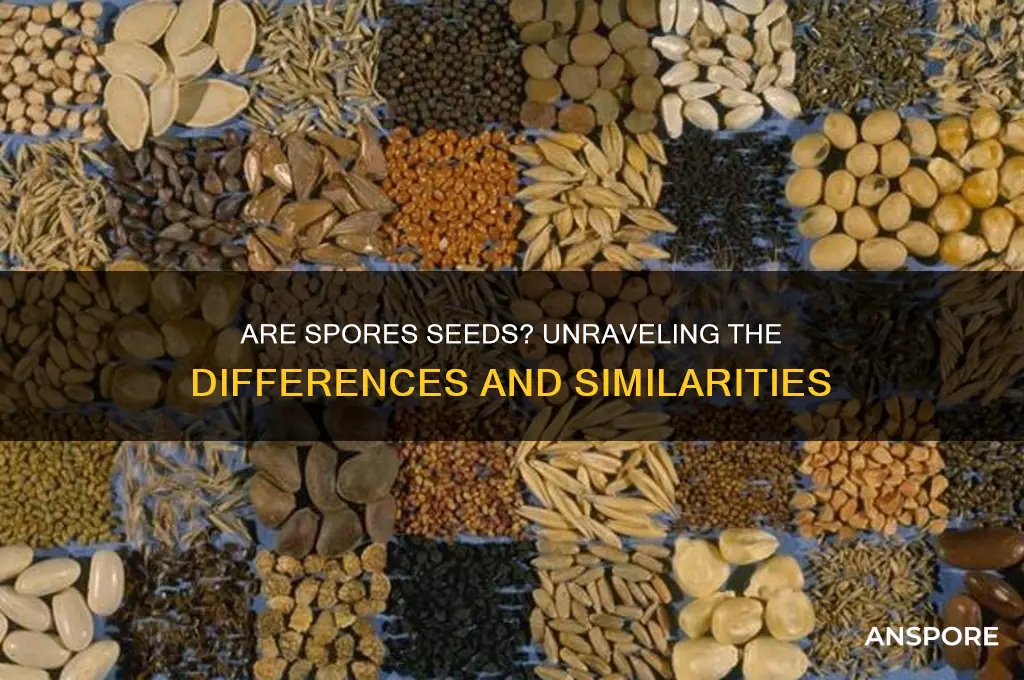

The question of whether spores are seeds is a fascinating one that delves into the reproductive strategies of different organisms. While both spores and seeds serve as dispersal units for their respective plants, they differ significantly in structure, function, and the organisms that produce them. Seeds are characteristic of flowering plants (angiosperms) and some non-flowering plants (gymnosperms), containing an embryo, stored food, and a protective coat. Spores, on the other hand, are produced by non-seed plants such as ferns, mosses, and fungi, as well as some bacteria and protozoa. Unlike seeds, spores are typically single-celled or consist of a few cells, lack an embryo, and do not store food. Instead, they are often lightweight and designed for wind or water dispersal, allowing them to colonize new environments efficiently. Understanding these distinctions highlights the diversity of reproductive mechanisms in the natural world.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Spores are reproductive units produced by plants, algae, fungi, and some bacteria, often single-celled and capable of developing into a new organism. Seeds are embryonic plants enclosed in a protective outer covering, typically produced by angiosperms (flowering plants) and gymnosperms (e.g., conifers). |

| Origin | Spores are produced by sporophytes (spore-bearing plants) through asexual or sexual reproduction, often via meiosis. Seeds are formed from the ovule of a flowering plant after fertilization, involving the fusion of male and female gametes. |

| Structure | Spores are typically unicellular, lightweight, and lack stored food reserves. Seeds are multicellular, contain an embryo, stored nutrients (endosperm), and a protective seed coat. |

| Dispersal | Spores are dispersed by wind, water, or animals due to their small size and lightweight nature. Seeds are dispersed via wind, water, animals, or explosive mechanisms, often aided by their size and structure (e.g., wings, hooks). |

| Dormancy | Spores can remain dormant for extended periods under harsh conditions. Seeds exhibit dormancy to ensure germination occurs under favorable conditions, regulated by internal and external factors. |

| Development | Spores develop directly into a new organism (e.g., gametophyte in plants) without an embryonic stage. Seeds develop into a new plant through germination, starting with the emergence of the radicle (embryonic root). |

| Taxonomic Group | Spores are found in non-seed plants (e.g., ferns, mosses), fungi, and some bacteria. Seeds are exclusive to seed plants (angiosperms and gymnosperms). |

| Size | Spores are microscopic (typically <0.1 mm). Seeds vary widely in size, from tiny orchid seeds to large coconut seeds. |

| Nutrient Storage | Spores generally lack stored nutrients and rely on external resources for growth. Seeds contain stored nutrients (endosperm or cotyledons) to support initial growth. |

| Protective Cover | Spores have minimal protection, often just a thin cell wall. Seeds are protected by a seed coat (testa) that shields the embryo from mechanical damage and pathogens. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore vs. Seed Definition: Key differences in structure, function, and reproductive strategies of spores and seeds

- Dispersal Mechanisms: How spores and seeds spread, including wind, water, animals, and self-propulsion

- Survival Adaptations: Spores' dormancy and resistance to harsh conditions compared to seeds' protective coats

- Reproductive Roles: Spores in fungi, ferns, and bacteria vs. seeds in flowering plants

- Evolutionary Significance: How spores and seeds evolved to dominate different ecosystems and species

Spore vs. Seed Definition: Key differences in structure, function, and reproductive strategies of spores and seeds

Spores and seeds, though both reproductive units, diverge fundamentally in structure, function, and reproductive strategies. Structurally, spores are typically single-celled and lack the complex internal organization of seeds. Seeds, in contrast, are multicellular embryos encased in a protective coat, often containing stored nutrients like endosperm or cotyledons. For instance, a fern releases lightweight, microscopic spores that disperse easily, while a sunflower produces seeds with a hard outer layer and nutrient reserves to support germination. This structural disparity reflects their distinct roles in survival and propagation.

Functionally, spores are primarily agents of asexual reproduction and dispersal, enabling organisms like fungi and non-seed plants to colonize new environments rapidly. Seeds, however, are products of sexual reproduction, combining genetic material from two parents to enhance diversity. Consider the resilience of fungal spores, which can remain dormant for years in harsh conditions, versus the immediate growth potential of a bean seed when planted in fertile soil. This functional difference underscores spores’ adaptability to adversity and seeds’ focus on establishing robust offspring.

Reproductive strategies further highlight the spore-seed dichotomy. Spores rely on sheer numbers and wind or water dispersal to ensure at least some land in favorable conditions, a strategy termed “hopeful dispersal.” Seeds, on the other hand, often employ sophisticated mechanisms like animal dispersal (e.g., hooks on burdock seeds) or explosive mechanisms (e.g., touch-me-not plant seeds) to target specific habitats. Additionally, seeds’ ability to remain dormant until conditions are optimal contrasts with spores’ immediate readiness to germinate upon landing in a suitable environment.

Practical implications of these differences are evident in horticulture and conservation. Gardeners can exploit spores’ hardiness by sowing them in challenging environments, such as shaded areas for mosses, but must provide seeds with precise conditions—adequate water, light, and soil depth—to ensure germination. For example, orchid seeds require specific fungi for nutrient uptake, while dandelion seeds thrive with minimal intervention. Understanding these distinctions empowers both amateur and professional cultivators to tailor their approaches effectively.

In summary, while spores and seeds share the purpose of reproduction, their structural simplicity versus complexity, asexual versus sexual origins, and scattergun versus targeted dispersal strategies reveal distinct evolutionary adaptations. Recognizing these differences not only clarifies their roles in biology but also informs practical applications, from gardening to ecosystem restoration. Whether you’re cultivating a fern or a flower, knowing whether you’re working with spores or seeds is the first step to success.

Discovering Reliable Sources for Mushroom Spores: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Dispersal Mechanisms: How spores and seeds spread, including wind, water, animals, and self-propulsion

Spores and seeds are nature's ingenious solutions for plant reproduction, but their dispersal mechanisms reveal distinct strategies shaped by size, structure, and environmental adaptation. While seeds, often encased in protective coats and nutrient stores, rely on external agents like wind, water, animals, or even explosive self-propulsion, spores—microscopic and lightweight—are primarily wind travelers, though some exploit water or animal vectors. Understanding these mechanisms highlights the evolutionary finesse behind plant survival and propagation.

Wind dispersal is a dominant strategy for both spores and seeds, but the execution differs dramatically. Spores, with their minuscule size (often 10–50 micrometers), are effortlessly carried by air currents, sometimes traveling thousands of miles. Ferns and fungi exemplify this, releasing spores in vast quantities to ensure at least a few land in suitable habitats. Seeds, however, require specialized adaptations for wind travel. Dandelions use feathery pappus structures, while maple seeds employ helicopter-like samaras to glide. Despite these innovations, seeds are generally heavier and less prolific than spores, making wind dispersal less efficient for them.

Water dispersal favors seeds more than spores, though exceptions exist. Coconut seeds, encased in buoyant husks, can drift across oceans for months before germinating on distant shores. Similarly, mangrove seeds float and root upon reaching mudflats. Spores, however, are rarely water-dispersed due to their fragility and susceptibility to desiccation. One exception is certain aquatic ferns, whose spores are adapted to survive in wet environments. This contrast underscores how seeds’ robust structures enable them to exploit water more effectively than the delicate spores.

Animal dispersal showcases the symbiotic relationships plants have evolved. Seeds often entice animals with fleshy fruits—think berries eaten by birds or nuts carried by squirrels. These animals inadvertently transport seeds in their digestive tracts or fur, depositing them elsewhere. Spores, lacking such allure, rarely rely on animals, though some fungi attach to insect exoskeletons for short-distance travel. A notable exception is the truffle fungus, whose spores are spread by animals attracted to its scent. This disparity highlights seeds’ proactive approach versus spores’ passive reliance on environmental factors.

Self-propulsion is a rare but fascinating mechanism, almost exclusive to seeds. Plants like the sandbox tree or touch-me-nots eject seeds explosively, using built-up tension or sudden drying to launch them meters away. Spores, lacking the necessary mass and structure, cannot achieve this. Instead, some fungi use turgor pressure to forcibly eject spores, but this is a localized mechanism compared to the seeds’ dramatic projection. This difference exemplifies how seeds invest in active dispersal, while spores prioritize quantity and wind reliance.

In practice, understanding these mechanisms can inform conservation efforts and gardening techniques. For instance, when planting wind-dispersed seeds like poppies, sow them in open areas with gentle breezes. For water-loving seeds like water lilies, ensure they’re placed in slow-moving or still water. Animal-dispersed seeds, such as acorns, benefit from being scattered in areas frequented by wildlife. While spores are less controllable, creating spore-friendly environments—like damp, shaded spots for ferns—can encourage their colonization. By mimicking nature’s dispersal strategies, we can enhance plant propagation success and biodiversity.

Extending Mushroom Spores Lifespan: Fridge Storage Tips and Duration

You may want to see also

Survival Adaptations: Spores' dormancy and resistance to harsh conditions compared to seeds' protective coats

Spores and seeds are both reproductive structures, but their survival strategies differ dramatically in response to environmental challenges. While seeds rely on protective coats to shield their delicate embryos, spores excel in dormancy and resistance to harsh conditions, often surviving extremes that would destroy most seeds. This distinction highlights the evolutionary ingenuity of these tiny survival pods.

Spores, produced by plants like ferns and fungi, enter a state of metabolic dormancy, slowing their biological processes to a near halt. This dormancy allows them to endure desiccation, extreme temperatures, and even radiation. For instance, bacterial endospores can survive for thousands of years, withstanding conditions as extreme as the vacuum of space. In contrast, seeds, though encased in protective layers, remain metabolically active to some degree, making them more vulnerable to prolonged stress.

Consider the protective mechanisms: seeds invest in physical barriers, such as hard shells or chemical inhibitors, to deter predators and resist environmental damage. A coconut’s thick husk is a prime example, enabling it to float across oceans while safeguarding its embryo. Spores, however, forgo such elaborate defenses, instead relying on their ability to shut down and revive when conditions improve. This minimalist approach allows spores to be lighter and more dispersible, a critical advantage in colonizing new habitats.

Practical applications of these adaptations are evident in agriculture and biotechnology. Farmers use seed coatings to enhance germination rates and protect against pests, but these measures are costly and labor-intensive. Spores, with their innate resilience, inspire innovations like desiccation-tolerant vaccines and long-term food preservation techniques. For example, researchers are exploring spore-like states in engineered organisms to create shelf-stable medicines for use in remote areas.

In summary, while seeds prioritize immediate protection, spores focus on long-term endurance. Understanding these differences not only sheds light on evolutionary strategies but also offers practical insights for technology and sustainability. Whether you’re a gardener, scientist, or survivalist, appreciating these adaptations can inform smarter choices in preserving life under challenging conditions.

Are Magic Mushroom Spores Illegal in Ohio? Legal Insights

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Reproductive Roles: Spores in fungi, ferns, and bacteria vs. seeds in flowering plants

Spores and seeds are both reproductive structures, but they serve distinct roles across different organisms, reflecting unique evolutionary adaptations. In fungi, ferns, and bacteria, spores are lightweight, resilient, and often produced in vast quantities, enabling dispersal over long distances and survival in harsh conditions. For example, a single mushroom can release up to 16 billion spores in a day, ensuring at least a few land in suitable environments. In contrast, seeds in flowering plants are nutrient-rich packages that provide embryos with a head start, often encased in protective coats and dispersed via animals, wind, or water. This fundamental difference highlights how spores prioritize quantity and durability, while seeds emphasize quality and immediate viability.

Consider the reproductive strategy of ferns, which rely on spores to colonize new habitats. Fern spores are microscopic, allowing them to travel on air currents and germinate in moist, shaded areas. Once a spore lands in a favorable spot, it develops into a gametophyte, a small, heart-shaped structure that produces eggs and sperm. This two-step life cycle contrasts sharply with flowering plants, where seeds contain a fully formed embryo, stored food, and a protective coat. For instance, an acorn (a seed) already contains a miniature oak tree, ready to grow once conditions are right. This comparison underscores how spores and seeds represent divergent solutions to the challenge of reproduction and survival.

Bacterial spores, such as those formed by *Bacillus anthracis*, take resilience to an extreme. These endospores can withstand boiling temperatures, radiation, and decades of dormancy, making them nearly indestructible. This adaptability is crucial for bacteria in unpredictable environments, where survival often depends on enduring extreme conditions. In contrast, seeds of flowering plants are not designed for such extremes. For example, tomato seeds lose viability after just a few years in storage unless preserved under optimal conditions. This disparity illustrates how spores and seeds are tailored to their respective ecological niches, with spores favoring longevity and seeds prioritizing immediate growth potential.

From a practical standpoint, understanding these differences has real-world applications. Gardeners can exploit the hardiness of fern spores to propagate rare species, while farmers rely on the nutrient reserves in seeds to ensure robust crop growth. For instance, sowing fern spores on a damp, sterile medium at room temperature can yield new plants within weeks. Conversely, seeds like those of sunflowers require specific soil conditions, water, and sunlight to germinate successfully. Additionally, bacterial spores’ resistance to sterilization methods informs protocols in food safety and medical settings, where complete decontamination is critical.

In conclusion, while both spores and seeds are reproductive structures, their roles and mechanisms diverge dramatically. Spores in fungi, ferns, and bacteria prioritize dispersal, durability, and survival in adverse conditions, often at the expense of immediate growth. Seeds in flowering plants, however, invest in protecting and nourishing the next generation, ensuring rapid development under favorable conditions. This distinction not only reflects evolutionary ingenuity but also offers practical insights for horticulture, agriculture, and microbiology. Whether you’re cultivating a garden or sterilizing equipment, understanding these reproductive strategies can guide more effective outcomes.

Fungal Sexual Spores: Haploid or Diploid? Unraveling the Mystery

You may want to see also

Evolutionary Significance: How spores and seeds evolved to dominate different ecosystems and species

Spores and seeds, though both reproductive units, have evolved distinct strategies to dominate diverse ecosystems. Spores, typically associated with plants like ferns and fungi, are lightweight, resilient, and capable of surviving extreme conditions. Seeds, on the other hand, are found in flowering plants and gymnosperms, offering protection and nourishment to developing embryos. This fundamental difference in structure and function reflects their evolutionary paths, tailored to specific environmental challenges.

Consider the analytical perspective: Spores thrive in environments where rapid dispersal and survival under harsh conditions are critical. For instance, fern spores can remain dormant for years, waiting for optimal moisture and light conditions to germinate. This adaptability allows spore-producing organisms to colonize disturbed or unpredictable habitats, such as volcanic slopes or arid regions. Seeds, however, evolved in more stable environments where competition for resources is high. Their protective coats and nutrient reserves enable seedlings to establish themselves quickly, outcompeting other plants in resource-rich ecosystems like forests and grasslands.

From an instructive standpoint, understanding these adaptations can guide conservation efforts. For example, in reforestation projects, using spore-based plants like mosses or ferns can stabilize soil in degraded areas, while seed-based plants like oaks or pines are better suited for long-term ecosystem restoration. Practical tips include: for spore-based plants, ensure high humidity and indirect light during germination; for seeds, scarify hard-coated varieties to improve water absorption and germination rates.

A comparative analysis highlights the trade-offs between spores and seeds. Spores’ simplicity and hardiness come at the cost of reduced immediate survival for individual spores, as they rely on numbers for success. Seeds, with their complexity, invest more energy per unit but yield higher survival rates for offspring. This evolutionary divergence explains why spore-bearing plants dominate in early successional stages or extreme environments, while seed-bearing plants dominate mature, stable ecosystems.

Finally, a descriptive approach illustrates their ecological impact. Imagine a post-wildfire landscape: spore-producing fungi and ferns quickly colonize the barren soil, breaking down debris and preparing the ground for future vegetation. In contrast, a temperate forest relies on seeds from trees and shrubs to maintain its structure and biodiversity. These contrasting roles demonstrate how spores and seeds have evolved not just to survive, but to shape the ecosystems they inhabit, each filling a unique niche in the web of life.

Moss Spores: Mitosis or Meiosis? Unraveling the Reproduction Mystery

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, spores and seeds are different. Spores are reproductive units produced by plants like ferns, fungi, and some algae, while seeds are produced by flowering plants (angiosperms) and gymnosperms like conifers.

Yes, spores can grow into new plants, but the process is different from seeds. Spores typically develop into gametophytes, which then produce gametes for reproduction, whereas seeds directly grow into new plants.

No, spores are not found in flowering plants (angiosperms). Instead, flowering plants produce seeds. Spores are more commonly associated with non-seed plants like ferns, mosses, and fungi.

Yes, spores are highly resilient and can survive extreme conditions such as drought, heat, and cold. This adaptability allows them to disperse widely and thrive in diverse environments, similar to how seeds can remain dormant until favorable conditions arise.