While both spores and sperm are reproductive structures, they serve distinct purposes and are found in different organisms. Spores are typically associated with plants, fungi, and some bacteria, functioning as a means of asexual reproduction and dispersal. They are highly resilient, capable of surviving harsh conditions, and can develop into new organisms without fertilization. In contrast, sperm are male reproductive cells found in animals and some plants, specifically designed for sexual reproduction. Sperm must fuse with a female egg (ovum) to form a zygote, which then develops into a new organism. Thus, while both spores and sperm are involved in reproduction, their mechanisms, structures, and roles differ significantly.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Structure Comparison: Spores are single-celled, reproductive units; sperm are specialized cells for fertilization

- Function Differences: Spores disperse and grow; sperm fertilize eggs for reproduction

- Organisms Involved: Spores in plants, fungi; sperm in animals, some protists

- Reproduction Methods: Spores in asexual/sexual cycles; sperm in sexual reproduction only

- Survival Mechanisms: Spores withstand harsh conditions; sperm short-lived, require fluid environment

Structure Comparison: Spores are single-celled, reproductive units; sperm are specialized cells for fertilization

Spores and sperm, though both involved in reproduction, differ fundamentally in structure and function. Spores are single-celled, self-contained units designed for survival and dispersal. They are often encased in a protective wall, enabling them to withstand harsh conditions such as extreme temperatures, desiccation, or chemical exposure. This resilience allows spores to remain dormant for extended periods until favorable conditions trigger germination. In contrast, sperm are specialized cells optimized for fertilization. Their structure is streamlined for mobility, featuring a flagellum (tail) that propels them toward the egg. Unlike spores, sperm lack a protective outer layer and are short-lived, relying on immediate access to a suitable environment for successful reproduction.

Analyzing their cellular composition reveals further distinctions. Spores contain a complete set of genetic material, making them capable of developing into a new organism independently. This self-sufficiency is critical for plants, fungi, and some bacteria, where spores serve as a means of asexual reproduction or dispersal. Sperm, however, carry only half the genetic material required for reproduction, necessitating fusion with an egg to form a zygote. This specialization reflects their role in sexual reproduction, where the combination of genetic material from two parents ensures genetic diversity. While spores are versatile and enduring, sperm are transient and purpose-driven, highlighting their divergent evolutionary adaptations.

From a practical perspective, understanding these structural differences has implications for fields like agriculture, medicine, and conservation. For instance, spore-based fungicides are used to control plant diseases due to their durability and ability to germinate under specific conditions. In contrast, sperm quality assessments are crucial in assisted reproductive technologies, where factors like motility and morphology directly impact fertilization success. For gardeners, knowing that spores require specific environmental cues (e.g., moisture, light) to activate can optimize seedling growth. Similarly, individuals undergoing fertility treatments may benefit from understanding how sperm health influences outcomes, emphasizing the importance of lifestyle factors like diet and stress management.

A comparative lens underscores the elegance of these structures in fulfilling their roles. Spores exemplify nature’s ingenuity in ensuring survival across generations, while sperm illustrate the precision required for successful sexual reproduction. For example, fern spores are microscopic and lightweight, allowing wind dispersal over vast distances, whereas human sperm are microscopic yet highly efficient swimmers, navigating complex environments to reach the egg. These adaptations reflect the distinct challenges each cell type faces, from enduring environmental extremes to achieving rapid fertilization. By studying these differences, scientists gain insights into reproductive strategies across species, informing advancements in biotechnology and conservation efforts.

In conclusion, while spores and sperm share a reproductive purpose, their structural differences are profound. Spores are self-sustaining, protective, and versatile, whereas sperm are specialized, transient, and dependent on immediate function. Recognizing these distinctions not only deepens our understanding of biology but also has practical applications in agriculture, medicine, and beyond. Whether you’re a gardener cultivating plants or an individual exploring fertility options, appreciating these cellular marvels enhances both knowledge and outcomes.

Are Mold Spores Contagious? Understanding Risks and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Function Differences: Spores disperse and grow; sperm fertilize eggs for reproduction

Spores and sperm, though both microscopic entities, serve fundamentally different purposes in the biological world. Spores are the resilient, dormant structures produced by plants, fungi, and some bacteria, designed to survive harsh conditions and disperse to new environments. Their primary function is to ensure the survival and propagation of the species by lying dormant until conditions are favorable for growth. In contrast, sperm are male reproductive cells in animals and some plants, specifically engineered to fertilize eggs, initiating the process of sexual reproduction. This distinction highlights their roles: spores are agents of dispersal and growth, while sperm are catalysts for genetic combination and offspring creation.

Consider the lifecycle of a fern, a plant that relies on spores for reproduction. When a fern releases spores into the wind, these tiny structures can travel vast distances, landing in diverse environments. Once a spore encounters suitable conditions—moisture, warmth, and soil—it germinates, growing into a new fern plant. This process is asexual, meaning the new plant is genetically identical to the parent. In contrast, sperm in humans, for example, are produced in the testes and released during ejaculation, containing half the genetic material needed to form a new individual. When a sperm successfully fertilizes an egg, it combines its genetic material with that of the egg, creating a unique offspring. This sexual reproduction ensures genetic diversity, a key advantage in adapting to changing environments.

From a practical standpoint, understanding these functional differences has real-world applications. In agriculture, spores of beneficial fungi can be applied to crops as biofertilizers, enhancing soil health and plant growth. For instance, mycorrhizal spores form symbiotic relationships with plant roots, improving nutrient uptake. Dosage is critical here: applying 5–10 grams of spore-rich inoculant per plant ensures effective colonization without waste. Conversely, in human fertility treatments like in vitro fertilization (IVF), sperm are carefully selected and prepared to maximize the chances of successful fertilization. Techniques such as intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) involve injecting a single sperm directly into an egg, bypassing natural barriers and increasing success rates for couples with male factor infertility.

The contrasting functions of spores and sperm also reflect broader evolutionary strategies. Spores exemplify the efficiency of asexual reproduction, allowing rapid colonization of new habitats without the need for a mate. This is particularly advantageous for organisms in stable but isolated environments, like certain fungi in forest ecosystems. Sperm, on the other hand, embody the complexity of sexual reproduction, which, while energetically costly, promotes genetic diversity and resilience in dynamic environments. For instance, coral reefs rely on mass spawning events where sperm and eggs are released simultaneously into the water, increasing the likelihood of fertilization and ensuring the survival of this biodiverse ecosystem.

In summary, while spores and sperm share microscopic dimensions, their functions diverge sharply. Spores are survivalists, dispersing and growing independently, while sperm are collaborators, fertilizing eggs to create new life. Recognizing these differences not only deepens our understanding of biology but also informs practical applications in fields like agriculture and medicine. Whether you’re a gardener using fungal spores to enrich your soil or a clinician optimizing sperm viability for fertility treatments, appreciating these distinctions is key to harnessing their potential effectively.

Bug Types and Spore Immunity: Debunking Myths in Pokémon Battles

You may want to see also

Organisms Involved: Spores in plants, fungi; sperm in animals, some protists

Spores and sperm, though both reproductive structures, serve distinct purposes across different organisms. Plants and fungi rely on spores, which are resilient, unicellular or multicellular units capable of developing into a new organism without fertilization. For instance, ferns release spores that germinate into tiny, heart-shaped gametophytes, which then produce eggs and sperm. In contrast, animals and some protists depend on sperm—highly specialized, motile cells designed to fertilize eggs. Human sperm, for example, are microscopic, flagellated cells that must swim through the female reproductive tract to reach and penetrate an egg, initiating embryonic development.

Consider the environmental adaptability of spores versus the precision of sperm. Fungal spores, such as those from mushrooms, can survive extreme conditions like drought or heat, lying dormant until favorable conditions return. This survival strategy allows fungi to colonize diverse habitats, from forest floors to decaying wood. Conversely, sperm in animals like salmon are short-lived and highly sensitive to their environment, requiring specific conditions (e.g., water temperature and pH) to remain viable during their journey to fertilize eggs. This contrast highlights how spores prioritize longevity and dispersal, while sperm focus on immediate reproductive success.

For those studying or working with these organisms, understanding their reproductive mechanisms is crucial. Gardeners, for instance, can harness spore dispersal to propagate plants like mosses or ferns by creating humid, shaded environments conducive to spore germination. Similarly, marine biologists monitoring coral reefs track sperm release during mass spawning events, often occurring at night under specific lunar phases, to assess reef health. Practical tips include using fine mesh screens to collect fungal spores for cultivation or optimizing water quality in aquaculture systems to enhance sperm motility in fish breeding programs.

A comparative analysis reveals that while both spores and sperm are reproductive units, their roles and characteristics diverge sharply. Spores act as survival and dispersal agents, enabling organisms to persist across generations and colonize new territories. Sperm, however, are transient and task-specific, embodying the immediacy of sexual reproduction in animals and certain protists. This distinction underscores the evolutionary trade-offs between resilience and efficiency, each tailored to the ecological demands of the organisms involved. By examining these differences, we gain insights into the diverse strategies life employs to perpetuate itself.

Can Heat Kill Mold Spores? Effective Temperatures and Methods Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Reproduction Methods: Spores in asexual/sexual cycles; sperm in sexual reproduction only

Spores and sperm are fundamentally different reproductive structures, each serving distinct purposes in the life cycles of organisms. While both are involved in reproduction, their roles, mechanisms, and contexts vary significantly. Spores are versatile, participating in both asexual and sexual reproduction, whereas sperm are exclusively involved in sexual reproduction. Understanding these differences is crucial for grasping the diversity of reproductive strategies in the biological world.

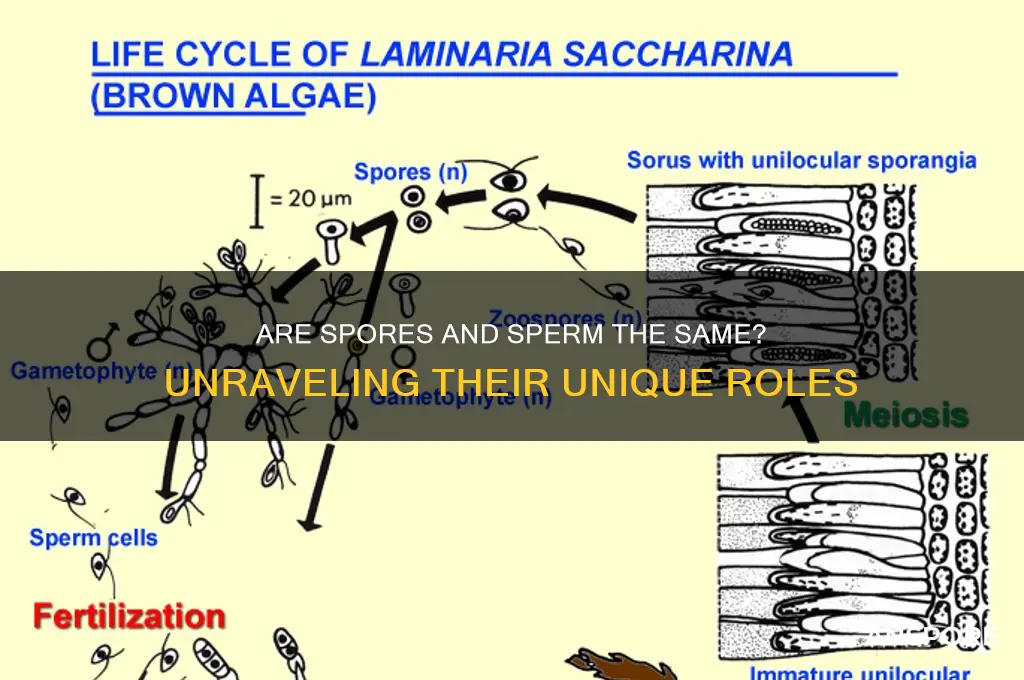

In asexual reproduction, spores act as self-contained units that can develop into new individuals without fertilization. For example, fungi like molds and mushrooms produce spores that disperse and grow into genetically identical offspring under favorable conditions. This method ensures rapid proliferation and survival in diverse environments. In contrast, sexual reproduction involving spores occurs in organisms like ferns and some algae, where spores develop into gametophytes that produce gametes (sperm and eggs) for fertilization. Here, spores serve as an intermediate stage, bridging asexual and sexual phases in the life cycle.

Sperm, on the other hand, are specialized cells designed solely for sexual reproduction. Found in animals, plants, and some protists, sperm are motile and carry half the genetic material required to form a new organism. Their role is to fertilize an egg, combining genetic information from two parents to create offspring with genetic diversity. Unlike spores, sperm cannot develop into new individuals independently; they require a complementary gamete to complete the reproductive process. This specialization highlights the distinct evolutionary adaptations of sperm for sexual reproduction.

A key distinction lies in the environmental and developmental contexts of spores and sperm. Spores are often resilient, capable of surviving harsh conditions such as drought or extreme temperatures, making them ideal for dispersal and long-term dormancy. For instance, bacterial endospores can remain viable for centuries. Sperm, however, are typically short-lived and require specific conditions to remain functional, such as the aqueous environment of reproductive tracts. This contrast underscores the divergent strategies of spores and sperm in ensuring reproductive success.

Practically, understanding these differences has implications in fields like agriculture, medicine, and conservation. For example, controlling fungal spore dispersal can manage crop diseases, while optimizing sperm viability is critical in assisted reproductive technologies. By recognizing the unique roles of spores and sperm, scientists and practitioners can develop targeted strategies to enhance or regulate reproductive processes in various organisms. This knowledge not only deepens our appreciation of biological diversity but also informs practical applications in real-world scenarios.

Are Mushroom Spores Legal in the US? Exploring the Legal Landscape

You may want to see also

Survival Mechanisms: Spores withstand harsh conditions; sperm short-lived, require fluid environment

Spores and sperm, though both reproductive units, exhibit starkly different survival strategies. Spores, produced by plants, fungi, and some bacteria, are designed to endure extreme conditions—desiccation, heat, cold, and even radiation. Their tough outer walls and dormant metabolic states allow them to persist for years, even centuries, until conditions become favorable for growth. In contrast, sperm are fragile, short-lived cells that require a fluid environment to remain viable. Without the protection of seminal fluid or a reproductive tract, they quickly degrade, typically surviving only a few hours outside the body. This fundamental difference highlights how each is adapted to its specific reproductive role.

Consider the practical implications of these survival mechanisms. For gardeners, understanding spore resilience means knowing that fungal spores in soil can remain dormant until moisture and warmth trigger germination, making fungal infections difficult to eradicate. Similarly, in food preservation, spores of bacteria like *Clostridium botulinum* can survive boiling temperatures, necessitating pressure canning to ensure safety. Conversely, sperm’s fragility is leveraged in fertility treatments, where they are carefully preserved in cryogenic conditions or controlled media to maintain viability. For couples trying to conceive, this underscores the importance of timing and environment in reproductive success.

From an evolutionary perspective, these mechanisms reflect distinct reproductive strategies. Spores are a bet-hedging tactic, ensuring survival across unpredictable environments. A single spore can disperse widely, waiting for the right moment to sprout. Sperm, however, are part of a high-stakes race, produced in vast numbers to increase the odds of fertilization. Their short lifespan is a trade-off for mobility and immediacy, relying on the fluid medium to transport them to the egg. This comparison reveals how nature tailors survival mechanisms to the specific challenges of each reproductive process.

To illustrate, imagine a scenario where a fern spore lands in a desert, surviving decades of aridity until a rare rainfall triggers growth. Contrast this with sperm, which, without the protective environment of the female reproductive tract, lose motility within minutes and die within hours. This disparity is not a flaw but a feature—spores are built for endurance, sperm for speed. For anyone studying or working with these cells, recognizing these differences is crucial. Whether in agriculture, medicine, or ecology, understanding these survival mechanisms can inform strategies for preservation, eradication, or optimization, depending on the goal.

Are Moss Spores Identical? Unveiling the Diversity in Moss Reproduction

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, spores and sperm are not the same. Spores are reproductive structures produced by plants, fungi, and some microorganisms, while sperm are male reproductive cells in animals and some plants.

While both are involved in reproduction, their purposes differ. Spores are used for asexual or sexual reproduction and dispersal, often in harsh conditions, whereas sperm fertilize female eggs to create offspring.

No, spores are typically found in plants (like ferns), fungi, and some protists, while sperm are found in animals and certain plants (like seed plants) that use sexual reproduction.

Sperm are motile and can move independently to reach the egg, but spores are generally non-motile and rely on wind, water, or other external factors for dispersal.