Spores are a fundamental aspect of the life cycle of many organisms, particularly within the kingdom Fungi. These microscopic, often single-celled structures serve as a means of reproduction and dispersal, allowing fungi to thrive in diverse environments. Fungi, which include mushrooms, molds, and yeasts, rely on spores to propagate and survive under adverse conditions. Unlike seeds in plants, fungal spores are typically haploid and can be produced both sexually and asexually, depending on the species. Understanding whether spores are exclusive to the kingdom Fungi is crucial, as it highlights the unique reproductive strategies of these organisms and distinguishes them from other life forms. While some other groups, such as bacteria and certain plants, also produce spore-like structures, the characteristics and functions of fungal spores are distinct, making them a defining feature of this kingdom.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Kingdom | Fungi |

| Reproductive Structures | Spores |

| Type of Spores | Asexual (e.g., conidia, sporangiospores) and Sexual (e.g., zygospores, ascospores, basidiospores) |

| Function | Reproduction and dispersal |

| Formation | Produced in specialized structures (e.g., sporangia, asci, basidia) |

| Dispersal Methods | Wind, water, animals, or mechanical means |

| Dormancy | Many spores can remain dormant for extended periods |

| Resistance | Highly resistant to harsh environmental conditions (e.g., heat, desiccation) |

| Size | Typically microscopic (ranging from 1 to 100 micrometers) |

| Shape | Varied (e.g., spherical, oval, filamentous) |

| Cell Wall Composition | Primarily chitin, providing structural support and protection |

| Metabolism | Spores are metabolically inactive until germination |

| Germination | Occurs under favorable conditions, leading to the growth of a new fungal individual |

| Ecological Role | Essential for fungal survival, colonization of new habitats, and ecosystem nutrient cycling |

| Examples of Spore-Producing Fungi | Molds, yeasts, mushrooms, and other fungi in Phyla Basidiomycota, Ascomycota, Zygomycota, and others |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Types: Fungi produce diverse spores like ascospores, basidiospores, conidia, and zygospores for reproduction

- Dispersal Methods: Spores spread via wind, water, animals, or explosive mechanisms to colonize new habitats

- Survival Strategies: Spores are resilient, surviving harsh conditions like drought, heat, and chemicals

- Germination Process: Spores activate under favorable conditions, growing into new fungal structures

- Ecological Role: Spores contribute to nutrient cycling, decomposition, and symbiotic relationships in ecosystems

Spore Types: Fungi produce diverse spores like ascospores, basidiospores, conidia, and zygospores for reproduction

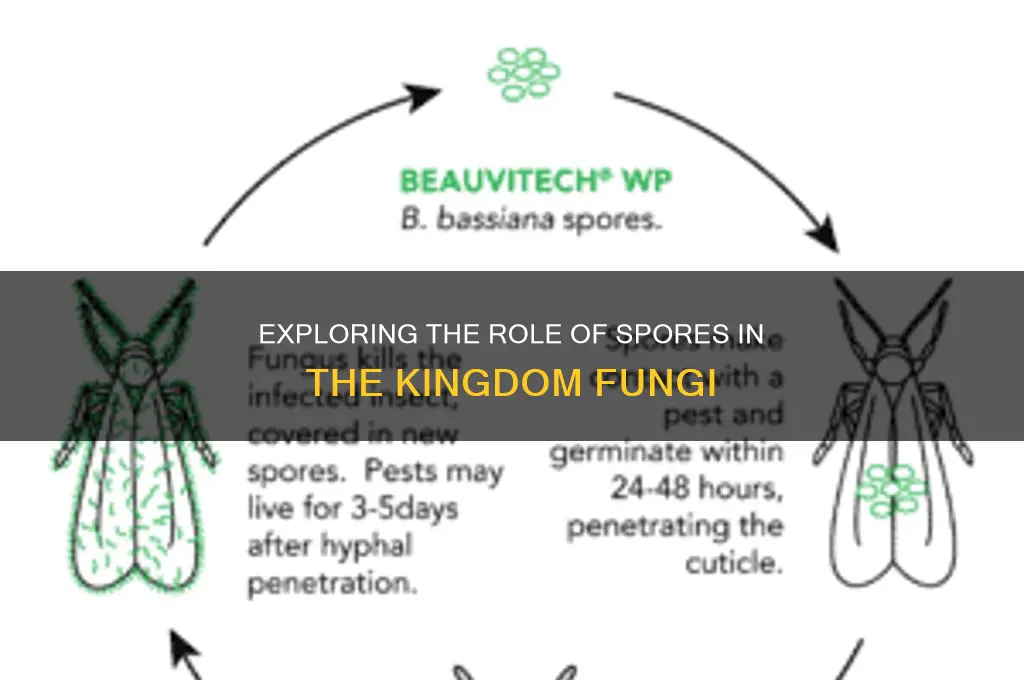

Fungi are masters of diversity, especially when it comes to reproduction. Unlike animals and plants, which rely on seeds or live birth, fungi produce spores—microscopic, single-celled structures designed for dispersal and survival. These spores are not one-size-fits-all; instead, fungi have evolved a variety of spore types, each adapted to specific environments and reproductive strategies. Among the most common are ascospores, basidiospores, conidia, and zygospores, each with unique characteristics that ensure the fungus’s survival and proliferation.

Consider ascospores and basidiospores, two spore types produced by fungi in the Ascomycota and Basidiomycota phyla, respectively. Ascospores develop within a sac-like structure called an ascus, which acts as a protective chamber until the spores are ready for release. This mechanism ensures that ascospores are ejected with force, increasing their dispersal range. Basidiospores, on the other hand, form on club-shaped structures called basidia. These spores are often associated with mushrooms and play a key role in the decomposition of organic matter. Both types are sexually produced, highlighting the complexity of fungal reproduction. For gardeners, understanding these spores can help in identifying fungal pathogens, such as the ascospore-producing *Botrytis cinerea*, which causes gray mold in plants.

Conidia offer a stark contrast to ascospores and basidiospores, as they are asexually produced and typically form at the ends of specialized hyphae. This method of reproduction allows fungi to multiply rapidly in favorable conditions. Conidia are lightweight and easily dispersed by wind or water, making them highly effective for colonization. For instance, the fungus *Aspergillus* produces conidia that can become airborne and cause respiratory issues in humans. To minimize exposure, ensure proper ventilation in damp areas like basements and bathrooms, where these fungi thrive.

Zygospores represent another fascinating adaptation in the fungal kingdom. Produced through the fusion of two compatible hyphae, zygospores are thick-walled and highly resistant to harsh conditions, such as drought or extreme temperatures. This dormancy allows fungi like *Rhizopus*, commonly found on bread molds, to survive until conditions improve. While zygospores are less common than other spore types, their resilience underscores the fungal ability to endure adversity. For food storage, this means keeping bread in a cool, dry place to prevent zygospore germination.

Each spore type reflects the fungal kingdom’s ingenuity in adapting to diverse ecosystems. Whether through the forceful ejection of ascospores, the mushroom-associated basidiospores, the rapid proliferation of conidia, or the resilience of zygospores, fungi ensure their survival and spread. For enthusiasts and professionals alike, recognizing these spore types can enhance understanding of fungal ecology and inform practical measures, from gardening to food preservation. By appreciating this diversity, we gain insight into the unseen world of fungi and their indispensable role in nature.

Are Spore Kits Legal? Understanding the Laws and Regulations

You may want to see also

Dispersal Methods: Spores spread via wind, water, animals, or explosive mechanisms to colonize new habitats

Spores, the microscopic units of reproduction in fungi, are nature's master dispersers, employing a variety of methods to travel far and wide. Among these, wind dispersal is perhaps the most common and efficient. Fungi like the common puffball (*Calvatia gigantea*) release billions of spores into the air, relying on wind currents to carry them to new habitats. These spores are incredibly lightweight, often measuring less than 10 micrometers in diameter, allowing them to remain suspended in the air for hours or even days. For gardeners and farmers, understanding this mechanism is crucial: wind-dispersed spores can quickly colonize new areas, making it essential to monitor and manage fungal populations in crops and greenhouses.

Water, too, plays a significant role in spore dispersal, particularly for fungi inhabiting aquatic or damp environments. Species like the water mold (*Saprolegnia*) release spores that are carried by water currents, enabling them to spread across ponds, streams, and even soil saturated with moisture. This method is especially effective in ecosystems where water flow is consistent, such as wetlands or riparian zones. For aquaculturists, this means that fungal infections can spread rapidly among fish or plants, necessitating proactive water management strategies, such as filtration systems or regular water changes, to mitigate risks.

Animals, both large and small, act as unwitting carriers of fungal spores, facilitating their dispersal across diverse landscapes. Spores can adhere to the fur, feathers, or exoskeletons of animals, or even be ingested and later excreted, allowing them to reach new habitats. For instance, birds visiting mushroom patches may carry spores on their feet or beaks to distant locations. Similarly, insects like flies and beetles are known to transport spores of fungi like *Coprinus comatus*. This symbiotic relationship highlights the interconnectedness of ecosystems and underscores the importance of biodiversity in fungal dispersal. Gardeners can leverage this by planting wildlife-friendly habitats to encourage natural spore dispersal.

Perhaps the most dramatic method of spore dispersal is through explosive mechanisms, where fungi forcibly eject spores into the environment. The cannonball fungus (*Sphaerobolus stellatus*) is a prime example, using internal pressure to launch spore-containing structures several feet away. This method ensures that spores are projected beyond the immediate vicinity of the fungus, increasing their chances of finding suitable substrates for growth. While fascinating, this mechanism can be problematic for homeowners, as these spores often land on and stain outdoor surfaces like patios or siding. Cleaning affected areas with a mixture of water and mild detergent can help remove spore stains, though prevention through regular inspection of woody mulch or decaying wood is ideal.

Each dispersal method—wind, water, animals, or explosive mechanisms—reflects the adaptability of fungi to their environments. By understanding these strategies, we can better manage fungal populations, whether in agricultural settings, natural ecosystems, or even our own backyards. For instance, knowing that wind-dispersed spores thrive in open areas can inform the placement of windbreaks, while awareness of water-borne spores can guide irrigation practices. Ultimately, the study of spore dispersal not only deepens our appreciation of fungal biology but also equips us with practical tools to coexist with these ubiquitous organisms.

Are Mold Spores Alive? Unveiling the Truth About Fungal Life

You may want to see also

Survival Strategies: Spores are resilient, surviving harsh conditions like drought, heat, and chemicals

Spores, the microscopic units of life produced by fungi, are nature’s ultimate survivalists. Encased in a tough, protective wall, they can endure conditions that would destroy most other life forms. This resilience is not just a passive trait but an active strategy honed over millennia, allowing fungi to thrive in environments ranging from scorching deserts to chemical-laden soils. Understanding how spores withstand drought, heat, and chemicals reveals the ingenuity of fungal survival mechanisms.

Consider the desert, where temperatures soar above 50°C (122°F) and rainfall is scarce. Spores of fungi like *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium* enter a state of dormancy, reducing metabolic activity to near zero. Their cell walls, composed of chitin and other polymers, act as a barrier against desiccation, preventing water loss and maintaining internal integrity. This adaptation allows spores to remain viable for decades, waiting for the rare moisture needed to germinate. For gardeners in arid regions, incorporating spore-rich compost into soil can introduce fungi that enhance nutrient cycling even in harsh conditions.

Heat resistance is another remarkable feature of spores. Some fungal spores, such as those of *Neurospora*, can survive temperatures exceeding 60°C (140°F) for extended periods. This is achieved through the production of heat-shock proteins, which stabilize cellular structures and prevent denaturation of essential enzymes. In industrial settings, this property is exploited in food preservation, where heat-resistant spores are used as indicators of sterilization efficacy. For home canners, ensuring temperatures reach 121°C (250°F) for at least 15 minutes can eliminate even the hardiest spores, preventing spoilage.

Chemical resistance is perhaps the most astonishing survival strategy of spores. Many fungi produce spores that withstand exposure to fungicides, heavy metals, and even radiation. For instance, *Cladosporium* spores can survive in soils contaminated with pesticides, breaking down toxins over time. This ability is attributed to their thick cell walls and the presence of melanin, a pigment that absorbs and dissipates harmful energy. Farmers dealing with contaminated fields can encourage the growth of such fungi by applying organic matter, which supports spore germination and soil remediation.

The takeaway is clear: spores are not just passive agents of fungal reproduction but active players in the survival of their species. Their resilience to drought, heat, and chemicals makes them indispensable in ecosystems and industries alike. Whether you’re a gardener, farmer, or scientist, understanding these strategies can help harness the power of fungi to address challenges from food preservation to environmental restoration. Spores remind us that even the smallest life forms can teach us the biggest lessons in adaptability.

Mycotoxin Spores: Are They Smaller Than 3 Microns?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Germination Process: Spores activate under favorable conditions, growing into new fungal structures

Spores, the microscopic units of fungal reproduction, lie dormant until environmental conditions trigger their awakening. This activation, known as germination, is a critical phase in the fungal life cycle, marking the transition from a quiescent state to active growth. The process begins when spores encounter specific cues such as moisture, temperature, and nutrient availability, which signal that the environment is conducive to survival and proliferation. For instance, *Aspergillus* spores require relative humidity levels above 80% and temperatures between 25°C and 37°C to initiate germination, while *Penicillium* spores thrive in cooler, damp environments. Understanding these triggers is essential for both harnessing fungi in biotechnology and controlling their spread in agricultural or clinical settings.

The germination process unfolds in distinct stages, starting with the absorption of water through the spore’s outer wall, a phenomenon known as imbibition. This rehydrates the spore and reactivates its metabolic processes, including enzyme production and nutrient uptake. Next, the spore’s nucleus becomes active, initiating DNA replication and protein synthesis. A small germ tube emerges from the spore, marking the beginning of vegetative growth. This tube elongates and branches, eventually developing into hyphae—the filamentous structures that form the fungal mycelium. In species like *Neurospora crassa*, this process takes approximately 6–8 hours under optimal conditions, showcasing the rapidity with which fungi can colonize new substrates.

Environmental factors play a pivotal role in determining the success of spore germination. For example, pH levels significantly influence the viability of spores; most fungi prefer slightly acidic to neutral conditions, with *Trichoderma* species germinating optimally at pH 5.0–6.0. Light exposure can also act as a stimulant or inhibitor, depending on the species. *Coprinus comatus*, commonly known as the shaggy mane mushroom, requires light to initiate germination, while *Alternaria alternata* spores are more likely to germinate in darkness. Practical applications of this knowledge include using controlled environments in laboratories to study fungal growth or implementing specific conditions in agriculture to suppress harmful fungi.

From a practical standpoint, manipulating germination conditions can be a powerful tool in various fields. In food preservation, for instance, maintaining low humidity and temperature can prevent the germination of mold spores on stored grains. Conversely, in mycoremediation—the use of fungi to degrade pollutants—creating optimal germination conditions enhances the efficiency of fungal activity. For hobbyists cultivating mushrooms, ensuring proper substrate moisture (typically 50–60% water content) and temperature (22°C–28°C for most species) is crucial for successful spore germination and fruiting body development. These examples underscore the importance of understanding and controlling the germination process to harness or mitigate fungal growth effectively.

In conclusion, the germination of fungal spores is a finely tuned response to environmental cues, transforming dormant units into thriving fungal structures. By dissecting the mechanisms and requirements of this process, we gain insights that are applicable across disciplines, from biotechnology to agriculture. Whether aiming to cultivate beneficial fungi or suppress harmful ones, the key lies in mastering the conditions that activate spores. This knowledge not only deepens our appreciation of fungal biology but also empowers us to manipulate these organisms for practical purposes, highlighting the intricate balance between dormancy and growth in the kingdom Fungi.

Are Mold Spores Fat Soluble? Unraveling the Science Behind It

You may want to see also

Ecological Role: Spores contribute to nutrient cycling, decomposition, and symbiotic relationships in ecosystems

Spores, the microscopic reproductive units of fungi, are ecological powerhouses. Their dispersal and germination drive nutrient cycling, decomposition, and symbiotic relationships across diverse ecosystems. These processes are fundamental to soil health, plant growth, and the overall balance of life on Earth.

Fungal spores act as nature's recyclers, breaking down complex organic matter into simpler forms. For instance, in forests, spores colonize fallen leaves and dead wood, secreting enzymes that decompose lignin and cellulose. This releases nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon back into the soil, fueling the growth of new vegetation. Without this fungal-driven decomposition, ecosystems would be buried under layers of undecomposed organic material, stifling productivity.

Consider the symbiotic relationships forged by spores, particularly in mycorrhizal associations. Over 90% of plant species, including most crops, form mutualistic partnerships with fungi. Spores germinate and penetrate plant roots, creating a network that enhances water and nutrient uptake. In return, plants supply fungi with carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis. This symbiotic relationship improves plant resilience to drought, disease, and nutrient deficiencies, demonstrating the critical role of spores in sustaining terrestrial ecosystems.

The ecological impact of spores extends beyond local interactions, influencing global nutrient cycles. For example, fungal spores contribute to the carbon cycle by decomposing organic matter and sequestering carbon in soil. This process helps mitigate climate change by reducing atmospheric CO2 levels. Additionally, spores facilitate the nitrogen cycle by converting atmospheric nitrogen into forms usable by plants, a process known as nitrogen fixation. This natural fertilization reduces the need for synthetic fertilizers, promoting sustainable agriculture.

To harness the ecological benefits of spores, consider practical applications in gardening and land management. Incorporate spore-rich compost or mycorrhizal inoculants into soil to enhance nutrient cycling and plant health. Avoid excessive tilling, as it disrupts fungal networks. In reforestation efforts, select tree species known to form strong mycorrhizal associations, such as oaks and pines, to accelerate ecosystem recovery. By understanding and supporting the role of spores, we can foster healthier, more resilient environments.

Does Vinegar Effectively Kill Mold Spores? A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, spores are a characteristic feature of the kingdom Fungi. They serve as reproductive structures and are essential for the dispersal and survival of fungi.

Spores play a critical role in the fungal life cycle by enabling reproduction, dispersal, and survival in adverse conditions. They can develop into new fungal organisms under favorable conditions.

Yes, all fungi produce spores as part of their life cycle, though the type and method of spore production vary among different fungal groups (e.g., molds, yeasts, mushrooms).

Fungal spores are haploid and primarily serve reproductive and dispersal functions, while plant spores (e.g., pollen, fern spores) are part of alternation of generations and can develop into gametophytes.