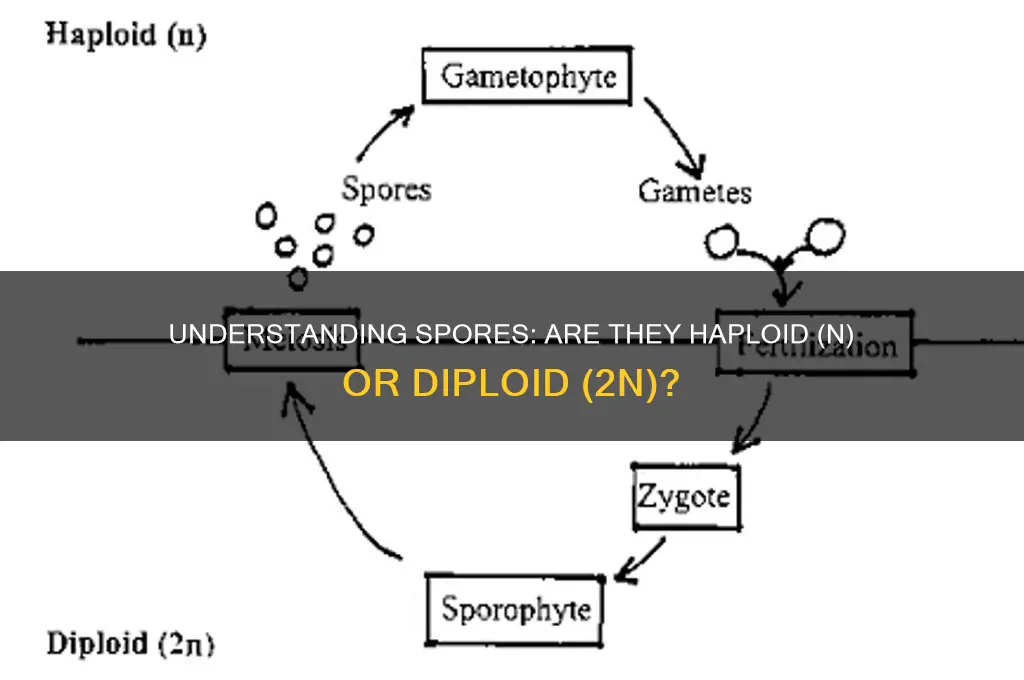

Spores are a critical reproductive structure in many organisms, particularly in plants, fungi, and some protists, but their ploidy—whether they are haploid (n) or diploid (2n)—varies depending on the organism and its life cycle. In fungi, spores are typically haploid (n), produced through meiosis, and serve as a means of dispersal and survival in adverse conditions. Conversely, in plants like ferns and mosses, spores are also haploid, but they develop into gametophytes, which then produce gametes for sexual reproduction. However, in certain algae and some fungi, spores can be diploid (2n), forming directly from mitosis or other asexual processes. Understanding whether spores are n or 2n is essential for grasping the reproductive strategies and life cycles of these diverse organisms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Ploidy of Spores in Plants | Haploid (n) |

| Plants Producing Haploid Spores | All plants (bryophytes, ferns, gymnosperms, angiosperms) |

| Process of Spore Formation | Meiosis (reduction division) |

| Function of Haploid Spores | Develop into gametophytes (e.g., pollen grains, embryo sacs) |

| Ploidy of Gametophytes | Haploid (n) |

| Ploidy of Zygote Formed | Diploid (2n) after fertilization |

| Exceptions or Special Cases | None; all plant spores are haploid (n) |

| Contrast with Diploid Structures | Sporophytes (diploid, 2n) produce spores via meiosis |

| Significance in Life Cycle | Alternation of generations (haploid gametophyte and diploid sporophyte phases) |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spores in Fungi: Are fungal spores haploid (n) or diploid (2n)

- Plant Spores (Bryophytes): Moss and fern spores: haploid (n) or diploid (2n)

- Fern Life Cycle: Alternation of generations: spores as n or 2n stages

- Spores vs. Gametophytes: Are spores n, and gametophytes 2n or vice versa

- Bacterial Spores: Are bacterial endospores haploid (n) or diploid (2n)

Spores in Fungi: Are fungal spores haploid (n) or diploid (2n)?

Fungal spores are predominantly haploid (n), a fundamental characteristic that distinguishes them from the spores of many other organisms. This haploid nature is a direct result of the fungal life cycle, which typically involves alternation of generations between a haploid and a diploid phase. In fungi, the haploid phase is dominant, and spores are produced through mitosis in the haploid mycelium. These spores, when they germinate, grow directly into new haploid individuals, perpetuating the cycle. This contrasts with organisms like plants, where spores can be haploid or diploid depending on the species and life cycle stage.

To understand why fungal spores are haploid, consider the process of sporulation in fungi. For example, in the model fungus *Aspergillus nidulans*, the haploid mycelium undergoes asexual reproduction by forming conidia, which are haploid spores. These conidia are genetically identical to the parent mycelium and can disperse to colonize new environments. When conditions are favorable, a conidium germinates, grows into a new haploid mycelium, and repeats the cycle. This simplicity in the life cycle allows fungi to rapidly adapt to changing environments, a key advantage in their ecological roles as decomposers and pathogens.

However, not all fungal spores are haploid. Some fungi, particularly those with more complex life cycles, produce diploid (2n) spores under specific conditions. For instance, in basidiomycetes like mushrooms, the fusion of haploid cells (karyogamy) results in a diploid zygote, which then undergoes meiosis to produce haploid basidiospores. Yet, in certain stages, such as during the formation of teliospores in rust fungi, diploid spores are produced. These diploid spores serve as a survival mechanism, allowing the fungus to withstand harsh conditions before germinating and returning to the haploid phase.

Practical implications of spore ploidy in fungi are significant, especially in agriculture and medicine. For example, understanding whether a fungal pathogen produces haploid or diploid spores can inform control strategies. Haploid spores, being genetically uniform, may be more susceptible to targeted fungicides, while diploid spores could exhibit greater genetic diversity, complicating management efforts. Additionally, in biotechnology, the haploid nature of fungal spores simplifies genetic studies, as mutations can be directly observed in the next generation without the complexity of diploid genetics.

In conclusion, while most fungal spores are haploid, exceptions exist, particularly in fungi with complex life cycles. This variability underscores the diversity of fungal reproductive strategies and their adaptability to different environments. For researchers, farmers, and clinicians, recognizing the ploidy of fungal spores is essential for effective management and utilization of these organisms. Whether haploid or diploid, fungal spores remain a fascinating and critical aspect of fungal biology, with far-reaching implications across multiple disciplines.

Do All Clostridium Species Form Spores? Unraveling the Truth

You may want to see also

Plant Spores (Bryophytes): Moss and fern spores: haploid (n) or diploid (2n)?

Plant spores, particularly those of bryophytes like mosses and ferns, are fundamentally haploid (n). This means each spore contains a single set of chromosomes, a critical feature of their life cycle. Unlike seeds in flowering plants, which are diploid (2n), spores are the product of meiosis, a process that reduces the chromosome number by half. This distinction is pivotal in understanding the alternation of generations, a hallmark of bryophyte and fern reproduction.

Consider the life cycle of a moss. It begins with a haploid spore germinating into a protonema, a thread-like structure that develops into a gametophyte. The gametophyte, still haploid, produces gametes (sperm and eggs) through mitosis. Only after fertilization does the zygote become diploid (2n), growing into a sporophyte. The sporophyte then undergoes meiosis to produce haploid spores, completing the cycle. This pattern ensures genetic diversity and adaptability, key traits for plants in diverse environments.

Ferns follow a similar alternation of generations, but with a more prominent sporophyte phase. Spores released from the underside of fern fronds are haploid and grow into heart-shaped gametophytes called prothalli. These prothalli produce gametes, and fertilization results in a diploid sporophyte. The sporophyte, the familiar fern plant, eventually produces spores via meiosis, perpetuating the haploid phase. This cycle highlights the evolutionary strategy of bryophytes and ferns, where the haploid stage is dominant and the diploid stage is transient.

Practical observation of these spores can be enlightening. For instance, collecting fern spores from the undersides of mature fronds and examining them under a microscope reveals their haploid nature. Similarly, moss spores, often dispersed in capsules called sporangia, can be observed to confirm their single chromosome set. Understanding this distinction is crucial for horticulture, conservation, and even educational demonstrations, as it underscores the unique reproductive strategies of these plants.

In summary, moss and fern spores are unequivocally haploid (n), a characteristic that defines their life cycles and sets them apart from diploid seeds of vascular plants. This knowledge not only enriches botanical understanding but also informs practical applications, from gardening to ecological restoration. By recognizing the haploid nature of these spores, we gain deeper insight into the resilience and diversity of bryophytes and ferns in the plant kingdom.

Mold Spores: Unveiling Their Role as Reproductive Structures

You may want to see also

Fern Life Cycle: Alternation of generations: spores as n or 2n stages

Spores in the fern life cycle are haploid (n), representing the gametophyte generation. This fundamental aspect of alternation of generations distinguishes ferns from plants with diploid spores, such as some algae and fungi. Understanding this haploid nature is crucial for grasping how ferns reproduce and develop.

Consider the fern life cycle as a relay race, where the baton passes between two distinct runners. The sporophyte (2n) generation, the familiar fern plant we see, produces spores through meiosis, reducing the chromosome number to n. These spores germinate into tiny, heart-shaped gametophytes, which are often overlooked but essential. Each gametophyte houses gametes—sperm and eggs—that unite to form a new sporophyte, completing the cycle. This alternation ensures genetic diversity and adaptability in varying environments.

From a practical standpoint, gardeners and botanists can leverage this knowledge to propagate ferns effectively. Spores, being haploid, are highly sensitive to moisture and light conditions. To cultivate ferns from spores, sow them on a sterile, moist medium in a shaded area. Maintain consistent humidity and avoid direct sunlight, as spores require specific conditions to germinate into gametophytes. Once the gametophytes mature, fertilization occurs naturally, leading to the growth of new sporophytes.

Comparatively, the haploid spore stage in ferns contrasts with diploid spore stages in other organisms, such as certain fungi. This difference highlights the evolutionary divergence in reproductive strategies. While diploid spores allow for immediate growth without fertilization, haploid spores in ferns necessitate a gametophyte phase, introducing genetic recombination. This distinction underscores the complexity and diversity of life cycles across the plant and fungal kingdoms.

In conclusion, the haploid (n) nature of fern spores is a cornerstone of their alternation of generations. This characteristic not only defines their life cycle but also offers practical insights for cultivation and propagation. By recognizing spores as the n stage, we gain a deeper appreciation for the intricate balance between genetic diversity and reproductive efficiency in ferns.

Are Spores Gram-Positive? Unraveling the Bacterial Classification Mystery

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Spores vs. Gametophytes: Are spores n, and gametophytes 2n or vice versa?

Spores and gametophytes are fundamental to the life cycles of plants, particularly in non-vascular plants like ferns and mosses, as well as in fungi. Understanding their ploidy levels—whether they are haploid (n) or diploid (2n)—is crucial for grasping their roles in reproduction and development. Spores, produced by sporophytes (2n), are typically haploid (n) and serve as dispersal units capable of growing into gametophytes. Gametophytes, in turn, are haploid (n) structures that produce gametes (sperm and eggs) for sexual reproduction. This alternation of generations ensures genetic diversity and adaptability in these organisms.

Consider the life cycle of a fern as a practical example. The visible fern plant is the sporophyte (2n), which produces spores (n) via meiosis. These spores germinate into small, heart-shaped gametophytes (n), often hidden in soil or damp environments. The gametophyte then produces sperm and eggs, which, upon fertilization, form a new sporophyte (2n). This cycle highlights the consistent pattern: spores and gametophytes are haploid (n), while sporophytes are diploid (2n). Misinterpreting these ploidy levels can lead to confusion in botanical studies or educational contexts.

To avoid common misconceptions, remember this rule of thumb: spores are always haploid (n), as they are produced by the reduction division of meiosis in the sporophyte. Gametophytes, being the product of spore germination, are also haploid (n) and serve as the sexual phase of the life cycle. Conversely, the sporophyte, which develops from a fertilized egg, is diploid (2n). This distinction is vital for students and researchers alike, as it underpins the alternation of generations in plants and fungi.

A practical tip for reinforcing this concept is to visualize the life cycle as a loop: sporophyte (2n) → spores (n) → gametophyte (n) → sporophyte (2n). Drawing or labeling diagrams can help solidify the relationship between ploidy levels and life cycle stages. For educators, incorporating hands-on activities, such as observing fern gametophytes under a microscope or simulating meiosis with colored beads, can make abstract concepts tangible.

In conclusion, spores and gametophytes are both haploid (n), while sporophytes are diploid (2n). This pattern is consistent across plants and fungi with alternation of generations. By focusing on the mechanisms of meiosis and fertilization, one can easily deduce the ploidy levels of each stage. Mastering this distinction not only clarifies botanical principles but also enhances appreciation for the intricate strategies organisms employ to survive and thrive.

Does Sterilization Kill Spores? Unraveling the Science Behind Effective Disinfection

You may want to see also

Bacterial Spores: Are bacterial endospores haploid (n) or diploid (2n)?

Bacterial endospores are not cells in the conventional sense, so the terms "haploid" (n) or "diploid" (2n) do not directly apply. Unlike eukaryotic spores, which are often reproductive structures with defined ploidy, bacterial endospores are dormant, highly resistant structures formed by certain bacteria as a survival mechanism. They are not involved in sexual reproduction or genetic recombination but rather serve as a means to endure harsh environmental conditions such as heat, desiccation, and chemicals.

To understand their genetic state, consider the process of endospore formation, or sporulation. During this process, a bacterium replicates its DNA and undergoes asymmetric cell division, resulting in a smaller cell (the forespore) and a larger cell (the mother cell). The forespore eventually becomes the endospore, retaining a single copy of the bacterial chromosome. This means the endospore is genetically identical to the original cell, carrying the same haploid genome (n) as the parent bacterium. Bacterial cells themselves are typically haploid, and this characteristic is preserved in the endospore.

A practical example of this can be seen in *Bacillus subtilis*, a well-studied spore-forming bacterium. When *B. subtilis* forms an endospore, the resulting structure contains one copy of its circular chromosome, maintaining its haploid state. This genetic simplicity is crucial for the spore’s function, as it ensures that the bacterium can quickly resume growth and replication once conditions improve, without the complexity of managing multiple chromosome sets.

From a practical standpoint, understanding the haploid nature of bacterial endospores is essential in fields like food safety and medicine. For instance, spores of *Clostridium botulinum* (n) can survive pasteurization temperatures, posing a risk in canned foods. Knowing their genetic state helps in designing targeted sterilization methods, such as using temperatures above 121°C for at least 15 minutes to ensure spore inactivation. Similarly, in healthcare, recognizing that endospores are haploid aids in developing antimicrobial strategies to combat spore-forming pathogens like *Bacillus anthracis*.

In summary, bacterial endospores are haploid (n), carrying a single copy of the bacterial genome. This characteristic is fundamental to their role as survival structures and has practical implications for industries ranging from food preservation to infection control. While the terms "haploid" and "diploid" originate from eukaryotic biology, applying this concept to bacterial endospores clarifies their genetic simplicity and functional efficiency.

Unveiling the Mystery: Where is the G Spot Located?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores can be produced by both haploid (n) and diploid (2n) cells, depending on the organism and its life cycle. In plants like ferns, spores are haploid (n), while in fungi like mushrooms, spores can be either haploid or diploid.

In the plant life cycle, spores are typically haploid (n). They are produced by the sporophyte (diploid, 2n) generation through meiosis and develop into the gametophyte (haploid, n) generation.

Fungi can produce both haploid (n) and diploid (2n) spores, depending on their reproductive strategy. For example, yeast produces haploid spores, while some molds produce diploid spores.

Bacterial spores are neither n nor 2n because bacteria are prokaryotes and do not undergo meiosis or have distinct haploid and diploid stages. Bacterial spores are simply dormant, resistant cells produced by certain bacteria for survival.