Spores are a fundamental aspect of fungal reproduction, serving as the primary means by which fungi propagate and disperse. Unlike plants and animals, fungi do not rely on seeds or offspring for reproduction; instead, they produce microscopic, single-celled spores that can be released into the environment. These spores are highly resilient, capable of surviving harsh conditions such as drought, extreme temperatures, and lack of nutrients. Once dispersed through air, water, or other vectors, spores germinate under favorable conditions, developing into new fungal individuals. This efficient reproductive strategy allows fungi to colonize diverse habitats and play crucial roles in ecosystems, such as decomposing organic matter and forming symbiotic relationships with plants. Thus, spores are not only essential for the survival and spread of fungi but also highlight their unique and adaptive reproductive mechanisms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Purpose | Spores are primarily used for asexual reproduction in fungi, allowing them to multiply and disperse. |

| Types | Fungi produce various types of spores, including conidia, sporangiospores, zygospores, ascospores, and basidiospores, depending on the fungal group. |

| Dispersal | Spores are lightweight and can be dispersed by wind, water, animals, or insects, enabling fungi to colonize new environments. |

| Dormancy | Spores can remain dormant for extended periods, surviving harsh conditions until favorable conditions for growth return. |

| Genetic Variation | Asexual spores are typically clones of the parent fungus, while sexual spores (e.g., zygospores, ascospores, basidiospores) result from genetic recombination, increasing diversity. |

| Structure | Spores are often single-celled and have a protective outer wall to withstand environmental stresses. |

| Role in Life Cycle | Spores are a critical part of the fungal life cycle, serving as the dispersal and survival stage in both asexual and sexual reproduction. |

| Examples | Molds (e.g., Penicillium) produce conidia, while mushrooms (e.g., Agaricus) release basidiospores. |

| Environmental Impact | Fungal spores play a key role in ecosystem processes, such as decomposition and nutrient cycling. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Spores as reproductive units

Spores are the microscopic, single-celled units fungi use to reproduce, functioning much like seeds in plants. Unlike seeds, however, spores are incredibly lightweight and can be dispersed over vast distances by wind, water, or animals. This adaptability allows fungi to colonize diverse environments, from forest floors to human lungs. For example, a single mushroom can release billions of spores in a day, ensuring at least some land in favorable conditions to grow into new fungal organisms.

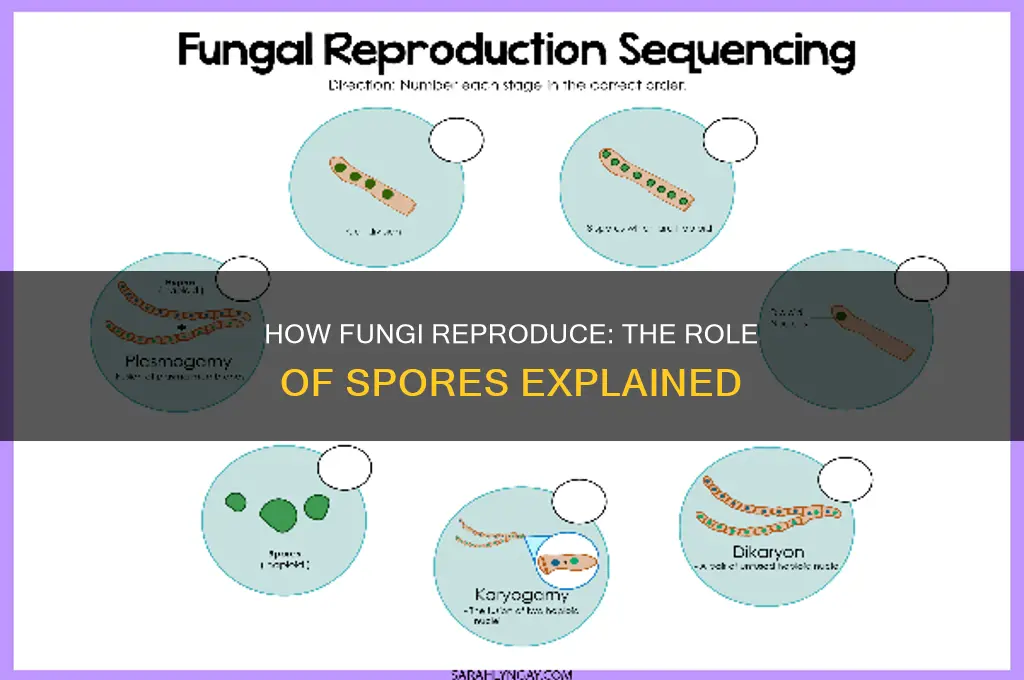

Analyzing the mechanics, spores are produced through both sexual and asexual processes, depending on the fungal species. In sexual reproduction, spores (often called meiospores) result from the fusion of gametes, introducing genetic diversity. This diversity is crucial for fungi to adapt to changing environments. Asexual spores, on the other hand, are clones of the parent fungus, produced rapidly through processes like budding or fragmentation. For instance, yeast, a single-celled fungus, reproduces asexually by budding, creating genetically identical offspring.

To harness spores for practical purposes, such as in agriculture or medicine, understanding their dispersal and germination is key. Spores require specific conditions—moisture, warmth, and a nutrient source—to sprout. In gardening, for example, inoculating soil with mycorrhizal spores can enhance plant root systems, improving nutrient uptake. However, caution is necessary: inhaling certain fungal spores, like those of *Aspergillus*, can cause respiratory infections, particularly in immunocompromised individuals.

Comparatively, spores’ efficiency as reproductive units outstrips that of many other organisms. Their small size and resilience enable them to survive harsh conditions, including extreme temperatures and desiccation. For instance, fungal spores have been found in Antarctic ice cores, dormant yet viable after thousands of years. This durability makes spores not only a cornerstone of fungal survival but also a subject of interest in astrobiology, where they’re studied as potential life forms capable of interstellar travel.

In conclusion, spores are not just reproductive units but marvels of evolutionary efficiency. Their ability to disperse widely, adapt genetically, and endure extreme conditions underscores their central role in fungal life cycles. Whether in ecological balance, agricultural innovation, or medical caution, understanding spores offers practical insights into managing and leveraging these microscopic powerhouses.

Unveiling the Spore-Producing Structures: A Comprehensive Guide to Identification

You may want to see also

Types of fungal spores

Fungal spores are not a one-size-fits-all solution to reproduction; they are a diverse toolkit, each type tailored to specific environmental challenges and survival strategies. Broadly, fungal spores fall into two main categories: asexual and sexual, each with distinct structures and functions. Asexual spores, such as conidia and sporangiospores, are produced rapidly in favorable conditions, allowing fungi to colonize new territories quickly. Sexual spores, like zygospores and ascospores, are more resilient, often surviving harsh conditions such as drought or extreme temperatures. Understanding these types is crucial for fields like agriculture, medicine, and ecology, where controlling fungal growth or harnessing their benefits is essential.

Consider the conidia, asexual spores produced at the ends of specialized hyphae called conidiophores. These spores are lightweight and easily dispersed by wind, making them ideal for fungi like *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium*. For instance, *Aspergillus flavus* releases conidia that can contaminate crops like peanuts, producing aflatoxins harmful to humans and livestock. To mitigate this, farmers can reduce spore dispersal by minimizing soil disturbance and using fungicides during critical growth stages. In contrast, conidia from *Penicillium* species are harnessed in biotechnology for producing antibiotics like penicillin, highlighting their dual role as both threat and tool.

Sexual spores, such as ascospores and basidiospores, are formed through genetic recombination, increasing fungal diversity and adaptability. Ascospores, produced within sac-like structures called asci, are common in fungi like *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* (baker’s yeast) and *Neurospora crassa* (orange bread mold). These spores are highly resistant to environmental stress, enabling long-term survival in soil or on plant debris. Basidiospores, released from club-shaped structures called basidia, are characteristic of mushrooms and bracket fungi. For example, the spores of *Agaricus bisporus* (button mushroom) are dispersed by wind, ensuring widespread colonization. Gardeners can encourage beneficial basidiomycetes by maintaining moist, organic-rich soil, fostering mycorrhizal relationships that enhance plant health.

A lesser-known but fascinating type is the zygospore, formed when two compatible hyphae fuse in zygomycetes like *Rhizopus*. These thick-walled spores are remarkably durable, surviving extreme conditions such as desiccation and freezing. While zygospores are less common in nature, their resilience makes them a subject of interest in astrobiology, where researchers study their potential to endure extraterrestrial environments. For hobbyists cultivating fungi, understanding zygospore formation can aid in preserving rare species or creating hybrid strains through controlled mating.

In practical terms, identifying spore types can guide effective management strategies. For instance, asexual spores like sporangiospores, produced in sporangia (e.g., in *Phycomyces*), are often associated with rapid, localized infections in plants. Gardeners can reduce their spread by removing infected plant material promptly and improving air circulation. Conversely, sexual spores like oospores, found in oomycetes such as *Phytophthora*, require specific conditions to germinate, making them targets for preventive measures like soil solarization. By tailoring approaches to spore biology, individuals can minimize fungal damage while promoting beneficial species, whether in a home garden or industrial setting.

Are Cubensis Spores Harmful to Dogs? A Safety Guide

You may want to see also

Dispersal mechanisms of spores

Spores are the primary means of reproduction and dispersal for fungi, enabling them to colonize new environments and survive harsh conditions. Their dispersal mechanisms are as diverse as the fungi themselves, each adapted to maximize reach and efficiency. From passive methods like wind and water to more active strategies involving animals and explosive discharges, these mechanisms ensure fungal survival and proliferation across ecosystems.

Consider the role of wind in spore dispersal, a mechanism favored by many fungi due to its simplicity and broad range. Spores released into the air can travel vast distances, carried by currents that transcend geographical barriers. For instance, the lightweight spores of *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium* are easily lofted, allowing them to colonize diverse habitats from soil to food storage areas. To optimize this method, fungi often produce spores in large quantities, increasing the likelihood of successful dispersal. Practical tip: In indoor environments, reducing air circulation can minimize spore spread, particularly in areas prone to mold growth.

Contrastingly, water serves as a dispersal medium for aquatic and semi-aquatic fungi, leveraging its flow to transport spores to new locations. Species like *Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis*, the chytrid fungus responsible for amphibian declines, release zoospores that swim through water before settling and germinating. This mechanism is highly effective in wet environments, where water bodies act as natural highways for spore movement. Caution: In conservation efforts, controlling waterborne spore spread is critical to preventing disease transmission among vulnerable species.

Animals, both large and small, also play a significant role in spore dispersal. Spores can adhere to fur, feathers, or exoskeletons, hitching rides to distant locations. For example, dung fungi rely on insects and mammals to transport their spores via fecal matter, ensuring colonization of fresh nutrient sources. Similarly, mycorrhizal fungi benefit from animal movement, as spores attached to roots or soil particles are carried to new areas. Takeaway: Understanding these interactions highlights the interconnectedness of fungi and their ecosystems, emphasizing the importance of biodiversity in maintaining fungal dispersal networks.

Finally, some fungi employ active mechanisms, such as explosive spore discharge, to propel spores away from the parent organism. The cannon-like discharge of *Pilobolus* spores, triggered by light and aimed toward light sources, demonstrates precision in targeting potential substrates. This method, while energy-intensive, ensures spores land in environments conducive to growth. Comparative analysis reveals that such active strategies, though less common, offer advantages in specific niches where passive dispersal may be less effective. Conclusion: The diversity of spore dispersal mechanisms underscores fungi’s adaptability, showcasing their evolutionary ingenuity in overcoming environmental challenges.

Are Mushroom Spores Legal in the US? Exploring the Legal Landscape

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$13.99 $17.99

Environmental triggers for spore release

Spores are indeed a primary means of reproduction for fungi, serving as resilient, lightweight structures capable of dispersing over vast distances. However, their release is not random; it is tightly regulated by environmental cues that signal optimal conditions for germination and survival. Understanding these triggers is crucial for both ecological research and practical applications, such as controlling fungal pathogens in agriculture or harnessing fungi for bioremediation.

Light and Temperature: The Dual Catalysts

Fungi are highly responsive to light and temperature, which act as critical environmental triggers for spore release. For instance, many basidiomycetes, including mushrooms, release spores during the cooler, humid hours of early morning, a phenomenon linked to dew formation and reduced air turbulence. Light intensity also plays a role; some fungi, like *Neurospora crassa*, exhibit phototropism, releasing spores in response to specific wavelengths of light. In controlled environments, such as greenhouses, manipulating light cycles (e.g., 12 hours of light followed by 12 hours of darkness) can induce spore release in certain species. Practical tip: For gardeners dealing with fungal pathogens, monitoring morning humidity levels and using shade cloths to alter light exposure can disrupt spore dispersal patterns.

Humidity and Rain: The Moisture Imperative

Moisture is another key trigger, with humidity and rain acting as signals for spore release in many fungal species. Raindrop impact on fungal structures, such as gills or pustules, can physically dislodge spores, a process known as rain splash dispersal. For example, rust fungi (*Puccinia* spp.) release spores in response to high humidity levels, often coinciding with rainfall. In agricultural settings, this knowledge is leveraged to time fungicide applications just before predicted rain events, when spore release is most likely. Caution: Over-reliance on humidity as a predictor can be misleading, as some fungi, like *Aspergillus*, thrive in dry conditions and release spores in response to water scarcity.

Nutrient Availability: The Substrate Signal

Fungi are adept at sensing nutrient availability in their environment, using it as a cue for spore release. For instance, when a fungus colonizes a nutrient-rich substrate, such as decaying wood or plant debris, it may delay spore release to maximize resource utilization. Conversely, nutrient depletion can trigger spore production and dispersal as the fungus seeks new habitats. In laboratory settings, researchers manipulate nutrient concentrations (e.g., reducing nitrogen levels by 30%) to induce sporulation in species like *Penicillium*. Takeaway: For mycologists cultivating fungi, adjusting nutrient levels in growth media can control the timing and quantity of spore release, optimizing yields for biotechnological applications.

Wind and Airflow: The Dispersal Mechanism

While not a direct trigger, wind and airflow are essential for spore dispersal once released. Fungi have evolved structures like spore cups (*apothecia*) or gills to facilitate wind-driven dispersal. For example, *Claviceps purpurea*, the ergot fungus, releases spores in response to air currents, ensuring they reach new host plants. In urban environments, HVAC systems can inadvertently spread fungal spores indoors, highlighting the importance of air filtration. Practical tip: To minimize indoor fungal contamination, use HEPA filters and ensure ventilation systems are regularly cleaned, especially in humid climates.

By recognizing these environmental triggers—light, temperature, humidity, nutrients, and airflow—we can better predict and manage fungal spore release. Whether combating pathogens or harnessing fungi for beneficial purposes, this knowledge empowers us to work in harmony with these microscopic powerhouses.

How Long Do Ringworm Spores Survive: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Role of spores in fungal survival

Spores are the microscopic, resilient units fungi produce to ensure their survival and propagation. Unlike seeds in plants, fungal spores are not the result of fertilization but are instead asexual or sexual structures designed for dispersal and endurance. These spores play a critical role in the fungal life cycle, enabling them to persist in harsh environments, colonize new habitats, and outlast unfavorable conditions. Their lightweight, durable nature allows them to travel vast distances via wind, water, or animals, ensuring fungal species can thrive across diverse ecosystems.

Consider the process of spore formation as a survival strategy. When environmental conditions deteriorate—such as nutrient depletion, extreme temperatures, or desiccation—fungi respond by producing spores. For example, *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium* fungi form conidia, asexual spores that can remain dormant for years until conditions improve. This dormancy is a key survival mechanism, allowing fungi to "wait out" adverse periods. Similarly, sexual spores like asci and basidiospores, produced through meiosis, introduce genetic diversity, enhancing the species' adaptability to changing environments.

The dispersal of spores is equally fascinating. Fungi lack mobility, so spores act as their agents of exploration. A single mushroom can release billions of spores daily, ensuring at least a few land in suitable environments. For instance, puffballs use explosive mechanisms to eject spores, while molds rely on air currents. This widespread dispersal minimizes competition for resources and maximizes the chances of successful colonization. Practical tip: If you’re a gardener, avoid disturbing soil with fungal growth to prevent spore release, which could lead to unwanted fungal spread.

From a comparative perspective, fungal spores outshine other microbial survival structures like bacterial endospores in their versatility. While bacterial endospores are primarily for endurance, fungal spores serve dual roles: survival and reproduction. This dual functionality makes spores indispensable for fungal longevity. For example, the spores of *Trichoderma* fungi not only survive extreme conditions but also actively inhibit pathogens, showcasing their ecological significance. Understanding this distinction highlights the evolutionary sophistication of fungal spores.

In conclusion, spores are not merely reproductive tools but lifeboats for fungi, ensuring their persistence in a dynamic world. Their ability to remain dormant, disperse widely, and adapt genetically underscores their central role in fungal survival. Whether you’re a mycologist, gardener, or simply curious about fungi, appreciating the role of spores offers insights into the resilience and ingenuity of these organisms. Practical takeaway: Store food in dry, cool conditions to prevent spore germination, as fungi thrive in moist environments.

Are Spore Syringes Legal in Australia? Understanding the Current Laws

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, spores are the primary method of reproduction for most fungi. They are specialized cells produced in large quantities and dispersed to colonize new environments.

Fungal spores are highly resilient and can survive harsh conditions such as drought, extreme temperatures, and lack of nutrients. This allows fungi to persist and spread even in unfavorable environments.

While most fungi reproduce via spores, some species can also reproduce asexually through fragmentation or budding. However, spore production remains the most common and widespread reproductive strategy in the fungal kingdom.