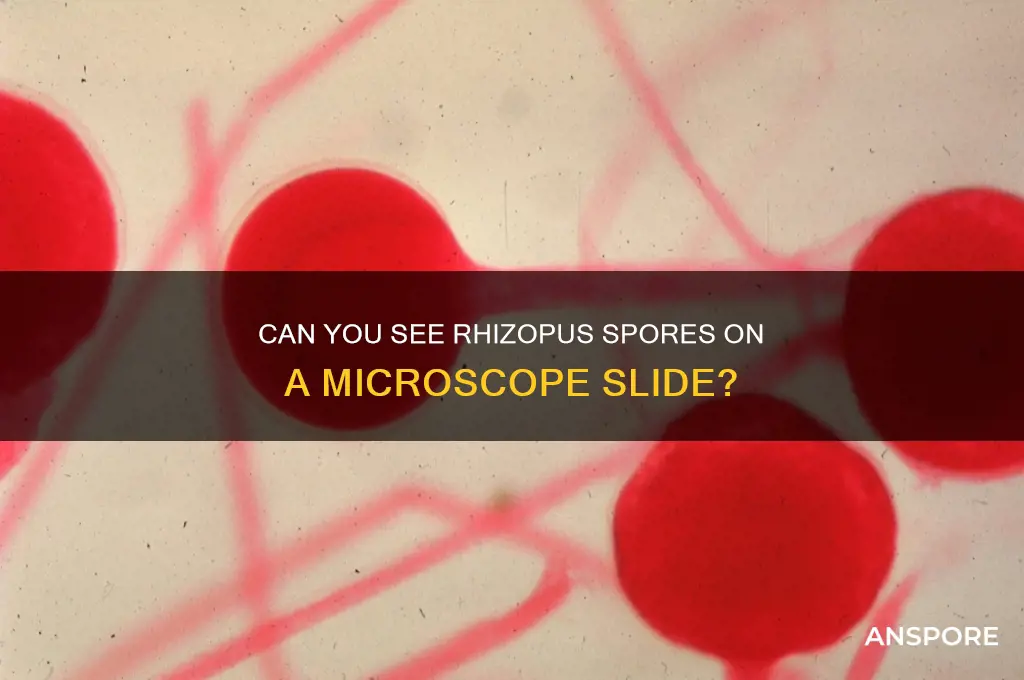

The question of whether spores are visible on a slide of *Rhizopus*, a common genus of fungi, is a fascinating aspect of microbiology and mycology. *Rhizopus* is known for its rapid growth and distinctive structures, including sporangia that contain numerous spores. When examining a slide under a microscope, the visibility of spores depends on factors such as magnification, staining techniques, and the developmental stage of the fungus. Typically, mature sporangia appear as rounded structures filled with spores, which can be observed as tiny, granular particles under appropriate conditions. However, without proper preparation or sufficient magnification, the spores may not be clearly discernible. Understanding the visibility of *Rhizopus* spores on a slide is crucial for educational, research, and diagnostic purposes, as it provides insights into the fungus's life cycle and morphology.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Visibility of Spores | Spores of Rhizopus are generally visible under a light microscope. |

| Spore Type | Zygospores (thick-walled, resistant spores) and sporangiospores (lighter, asexual spores). |

| Size of Spores | Sporangiospores: ~5–10 μm in diameter; Zygospores: larger, up to 50 μm. |

| Color of Spores | Sporangiospores: typically colorless or pale; Zygospores: dark brown or black. |

| Location on Slide | Spores are found within sporangia (asexual) or as zygospores (sexual) on the mycelium. |

| Microscopic Appearance | Sporangiospores appear as round, smooth structures; zygospores are thicker and more robust. |

| Staining Requirement | Often visible without staining, but stains like lactophenol cotton blue can enhance contrast. |

| Magnification Needed | Typically visible at 400x–1000x magnification. |

| Common Observations | Sporangia appear as round, balloon-like structures filled with spores. |

| Reproductive Structures | Sporangia (asexual) and zygosporangia (sexual) are visible on the slide. |

| Clarity on Slide | Spores are usually clear and distinct when properly prepared. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporangia Structure and Size: Observing sporangia under microscope, their size, shape, and visibility on Rhizopus slide

- Spore Release Mechanism: How spores are released from sporangia and their dispersal patterns

- Staining Techniques: Methods to enhance spore visibility using stains like lactophenol cotton blue

- Magnification Requirements: Optimal magnification levels to clearly visualize spores on the slide

- Comparison with Other Fungi: Differentiating Rhizopus spores from those of similar fungal species

Sporangia Structure and Size: Observing sporangia under microscope, their size, shape, and visibility on Rhizopus slide

Under a microscope, the sporangia of *Rhizopus* are immediately striking due to their distinct spherical or oval shape, often likened to tiny balloons perched atop the hyphae. These structures, typically 100 to 500 micrometers in diameter, are large enough to be visible under low magnification (40x to 100x), making them a prime target for observation in microbiology labs. Their size and shape are not merely aesthetic; they serve a critical function in spore dispersal, ensuring the fungus’s survival and propagation. When examining a *Rhizopus* slide, the sporangia’s prominence allows even novice observers to identify them with relative ease, provided the slide is properly prepared and stained.

To observe sporangia effectively, begin by preparing a wet mount of *Rhizopus* on a clean microscope slide. Place a small piece of bread or fruit with visible mold growth onto the slide, add a drop of water, and cover with a coverslip. This simple technique preserves the sporangia’s three-dimensional structure while minimizing distortion. Under low magnification, scan the slide for the characteristic radiating hyphae of *Rhizopus*. Gradually increase magnification to 100x or 400x to observe the sporangia in detail. Note their position at the tips of the sporangiophores, the long, stalk-like structures that elevate them for optimal spore release. A gentle tap on the slide may cause the spores within to shift, providing dynamic evidence of their presence.

While sporangia are easily visible, their contents—the spores—require closer inspection. Each sporangium houses hundreds to thousands of spores, typically 5 to 10 micrometers in diameter. At 400x magnification, these spores may appear as a fine, granular dust within the sporangium, especially if the structure is mature and ready for dispersal. For a clearer view, consider staining the slide with a mild dye like cotton blue or lactophenol cotton blue, which enhances contrast and highlights the spores’ boundaries. This step is particularly useful for distinguishing between immature and mature sporangia, as the former may contain fewer, less distinct spores.

A comparative analysis of *Rhizopus* sporangia with those of other fungi underscores their unique adaptability. Unlike the smaller, more numerous spores of *Aspergillus* or the elongated sporangia of *Mucor*, *Rhizopus* sporangia are optimized for rapid dispersal in open environments. Their size and shape facilitate efficient wind-borne dispersal, a trait that aligns with *Rhizopus*’s role as a decomposer in nutrient-rich substrates like bread or fruit. This ecological niche is reflected in their microscopic structure, making them an excellent subject for studying fungal morphology and function.

In practical terms, observing *Rhizopus* sporangia under a microscope is not just an academic exercise but a gateway to understanding fungal life cycles. For educators, this activity offers a tangible way to teach concepts like spore formation and dispersal. For hobbyists or students, it’s a reminder of the hidden complexity in everyday mold. To maximize visibility, ensure proper slide preparation, use adequate lighting, and experiment with magnification levels. With patience and attention to detail, the sporangia of *Rhizopus* reveal their secrets, bridging the microscopic and macroscopic worlds in a single slide.

Fungal Spores vs. Fruiting Bodies: Understanding the Key Differences

You may want to see also

Spore Release Mechanism: How spores are released from sporangia and their dispersal patterns

Spores of *Rhizopus*, a common zygomycete fungus, are housed within sporangia, which are spherical structures atop hyphae. When mature, these sporangia undergo a dramatic transformation: their walls dry out and split open, releasing thousands of spores into the environment. This mechanism, known as dehiscent spore release, is a passive yet highly effective strategy for dispersal. The process is triggered by environmental cues such as humidity changes, ensuring spores are released under optimal conditions for survival and germination.

To observe this phenomenon on a slide, prepare a fresh *Rhizopus* culture on bread or agar, allow it to sporulate (typically within 2–3 days), and gently place a coverslip over the sporangia. Under a microscope at 40x–100x magnification, you’ll notice the sporangia as round, bulbous structures. If the slide is prepared correctly, you may even witness the sporangial walls rupturing, releasing a cloud of spores. These spores, measuring 5–10 μm in diameter, are visible as tiny, round particles, often appearing in clusters before dispersing.

The dispersal patterns of *Rhizopus* spores are shaped by both biophysical and environmental factors. Once released, spores are lightweight and easily carried by air currents, a process known as aerodynamic dispersal. This allows them to travel significant distances, colonizing new substrates. Additionally, spores can adhere to surfaces via electrostatic charges or be transported by insects, enhancing their spread. The combination of passive release and diverse dispersal methods ensures *Rhizopus* can thrive in various environments, from kitchens to soil.

For practical observation, ensure the slide is not overcrowded with fungal growth, as this can obscure the sporangia. Use a moist environment during preparation to maintain sporangial integrity until viewing. If spores are not immediately visible, gently tap the slide to simulate air movement, which may trigger spore release. This hands-on approach not only aids in understanding the mechanism but also highlights the adaptability of *Rhizopus* in its life cycle.

Is Spore Available on Xbox? Exploring Compatibility and Gaming Options

You may want to see also

Staining Techniques: Methods to enhance spore visibility using stains like lactophenol cotton blue

Spores of *Rhizopus*, a common zygomycete fungus, are often challenging to visualize under a microscope due to their transparency and small size. To address this, staining techniques like lactophenol cotton blue (LCB) are employed to enhance contrast and highlight structural details. LCB is a compound stain consisting of cotton blue, a basic dye, dissolved in a lactophenol solution, which acts as a mounting medium and preservative. When applied, the cotton blue selectively stains chitin in fungal cell walls, turning spores and hyphae a distinct blue-green color, making them easily discernible against a clear background.

The process of staining with LCB is straightforward but requires precision. Begin by preparing a wet mount of the *Rhizopus* sample on a microscope slide. Add a drop of LCB to one side of the coverslip, allowing the stain to wick through the sample via capillary action. This method ensures even distribution without disturbing the specimen. Let the slide sit for 5–10 minutes to allow the stain to penetrate the fungal structures fully. Excess stain can be blotted with filter paper, and the slide is then ready for examination under a light microscope. Proper staining not only enhances visibility but also preserves the sample for extended observation.

While LCB is highly effective, its application must be balanced with caution. Over-staining can lead to excessive background coloration, obscuring finer details. Conversely, under-staining may result in faint or uneven visibility of spores. Optimal results are achieved by using a 1:1 ratio of LCB to the sample and ensuring the stain is fresh, as older solutions may lose potency. For educational or research purposes, this technique is invaluable, as it transforms nearly invisible spores into clearly defined structures, facilitating accurate identification and analysis of *Rhizopus*.

Comparatively, LCB outperforms other stains like methylene blue or safranin in fungal studies due to its dual role as a stain and mounting medium. Its ability to preserve samples for months makes it a preferred choice in mycology. However, it is not suitable for live specimens, as the lactophenol component is toxic to fungi. For dynamic observations, alternative techniques like calcofluor white, a fluorescent stain, may be more appropriate. Nonetheless, for static, detailed visualization of *Rhizopus* spores, LCB remains the gold standard, combining simplicity, effectiveness, and longevity in a single application.

Spore Bacteria Shapes: Filament or Rod? Unraveling the Mystery

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$64.99 $69.99

Magnification Requirements: Optimal magnification levels to clearly visualize spores on the slide

Spores of *Rhizopus*, a common zygomycete fungus, are typically 10–20 micrometers in diameter, placing them at the upper limit of visibility under low-magnification microscopy. To clearly visualize these structures on a slide, understanding the optimal magnification levels is critical. A 10x objective lens, paired with a 10x eyepiece, provides a total magnification of 100x, which is often sufficient to discern the general shape and size of *Rhizopus* spores. However, for detailed examination of spore walls, sporangia, or hyphal structures, higher magnification is necessary. A 40x objective lens, yielding 400x total magnification, strikes a balance between resolution and field of view, allowing for clear observation of spore morphology without excessive pixelation or loss of context.

Selecting the appropriate magnification is not merely a matter of preference but a function of the microscope’s numerical aperture and the specimen’s preparation. *Rhizopus* spores are often mounted in a wet mount with a lacto-phenol cotton blue stain, which enhances contrast and highlights cellular structures. At 100x magnification, spores appear as round to oval bodies, often clustered within sporangia. However, finer details, such as spore ornamentation or the presence of appendages, require 400x magnification. Beyond this, a 100x objective lens (1000x total magnification) may be employed, but it demands precise focus and a thinner specimen, as depth of field decreases significantly at higher magnifications.

For educational or diagnostic purposes, starting with 100x magnification provides a broad overview of *Rhizopus* structures, enabling identification of sporangiospores and their arrangement. Transitioning to 400x allows for closer inspection of spore viability, germination patterns, or abnormalities. Caution must be exercised at 1000x, as improper slide preparation or focus can render the image unusable. Additionally, oil immersion techniques, typically used with 100x objectives, are rarely necessary for *Rhizopus* spores due to their relatively large size but can be employed for ultra-fine details.

In practice, the choice of magnification should align with the observer’s goals. For students or hobbyists, 100x and 400x magnifications are adequate for most observations. Researchers or clinicians, however, may require 1000x to assess spore integrity or interactions with other microorganisms. Regardless of the magnification level, proper lighting and staining techniques are essential to optimize visibility. A brightfield microscope with adjustable intensity and a condenser diaphragm ensures even illumination, while differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy can further enhance spore features without staining.

Ultimately, the optimal magnification for visualizing *Rhizopus* spores depends on the level of detail required. A tiered approach—beginning with 100x for orientation, progressing to 400x for detailed analysis, and reserving 1000x for specialized investigations—maximizes efficiency and clarity. By mastering these magnification levels and their applications, observers can fully explore the intricate world of *Rhizopus* spores with precision and confidence.

Are Mold Spores Fat Soluble? Unraveling the Science Behind It

You may want to see also

Comparison with Other Fungi: Differentiating Rhizopus spores from those of similar fungal species

Rhizopus, a common mold found on decaying organic matter, produces spores that are often visible under a microscope. However, distinguishing Rhizopus spores from those of similar fungi requires careful observation and knowledge of their unique characteristics. For instance, while Rhizopus spores are typically rounded and borne on tall, erect sporangiophores, those of Mucor, a closely related genus, are similar in shape but often appear more elongated and may have a slightly different texture when viewed under high magnification.

To differentiate Rhizopus spores from those of other fungi, start by examining the sporangiophores. Rhizopus sporangiophores are unbranched and terminate in a spherical sporangium, which contains the spores. In contrast, sporangiophores of Absidia, another similar fungus, are often branched, and their sporangia may appear more elongated or irregular in shape. Additionally, the size of the sporangia can be a distinguishing factor: Rhizopus sporangia are generally larger, ranging from 100 to 300 micrometers in diameter, compared to the smaller sporangia of Absidia, which typically measure between 50 and 150 micrometers.

Another critical feature for identification is the presence of columellae, the structures within the sporangium that support the spores. In Rhizopus, the columella is typically simple and centrally located, whereas in Mucor, it may be more complex or branched. Observing these structures requires a high-power objective (40x or 100x) and proper staining techniques, such as using lactophenol cotton blue, to enhance visibility and contrast. For beginners, practicing on prepared slides of both Rhizopus and Mucor can help in mastering these distinctions.

When comparing Rhizopus spores to those of Aspergillus, a fungus commonly found in indoor environments, the differences become more pronounced. Aspergillus produces conidia, which are asexual spores arranged in chains on structures called conidiophores. These conidia are typically smaller, ranging from 2 to 5 micrometers, and have a rough, textured appearance compared to the smooth, rounded spores of Rhizopus. Aspergillus conidiophores also have a distinctive "bottlebrush" appearance, which is absent in Rhizopus.

In practical terms, accurate identification is crucial for applications like food safety, where Rhizopus can cause spoilage, or in clinical settings, where distinguishing it from pathogenic fungi is essential. For example, while Rhizopus is generally non-pathogenic, Mucor can cause mucormycosis, a serious infection in immunocompromised individuals. Thus, understanding these morphological differences not only aids in taxonomic classification but also has real-world implications for health and industry. By focusing on sporangiophore structure, sporangium size, and columella characteristics, even novice microscopists can confidently differentiate Rhizopus spores from those of similar fungi.

Exploring Fern Reproduction: Do Ferns Bear Spores for Growth?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, spores of Rhizopus, known as sporangiospores, are typically visible under a light microscope at 40x to 100x magnification. They appear as small, round structures clustered within the sporangium at the tip of the sporangiophore.

A magnification of 40x to 100x is sufficient to clearly observe Rhizopus spores on a slide. Higher magnification may be used for detailed examination of spore structure.

Yes, Rhizopus spores can be distinguished by their characteristic arrangement in a spherical sporangium at the end of a long, erect sporangiophore. Their size, shape, and clustering pattern help differentiate them from spores of other fungi.