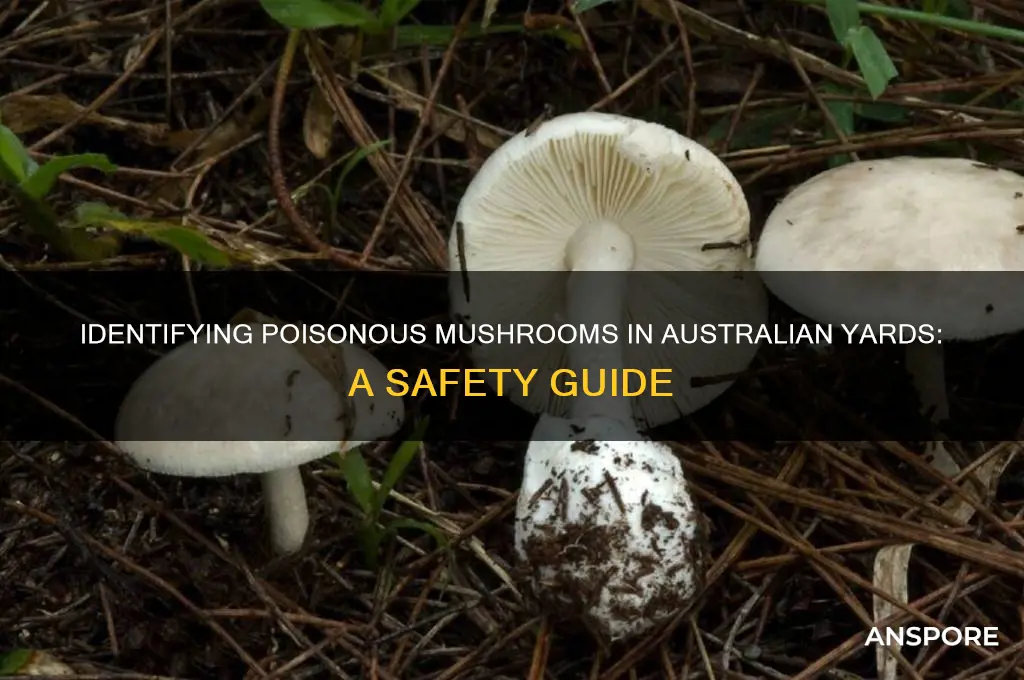

If you’ve noticed mushrooms sprouting in your Australian yard, it’s natural to wonder whether they’re safe or potentially poisonous. Australia is home to a diverse range of fungi, including both edible and toxic species, and misidentification can have serious health consequences. Common backyard mushrooms like the Amanita genus, for instance, can be deadly, while others may cause mild to severe symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, or organ damage. Without proper knowledge or expert guidance, it’s risky to assume any wild mushroom is safe. Always avoid consuming or handling unfamiliar fungi, and consider consulting a local mycologist or using reliable resources to identify them accurately. When in doubt, it’s best to leave them undisturbed and appreciate them from a safe distance.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Common Poisonous Species | Death Cap (Amanita phalloides), Funeral Bell (Galerina marginata), Yellow Stainer (Agaricus xanthodermus) |

| Common Edible Species | Field Mushroom (Agaricus campestris), Slippery Jack (Suillus luteus), Pine Mushroom (Tricholoma matsutake) |

| Key Poisonous Features | White or greenish gills, bulbous base with cup-like volva, foul smell (e.g., raw potato or garlic), sudden onset of symptoms (e.g., vomiting, diarrhea, liver failure) |

| Key Edible Features | Pink or brown gills, absence of volva, pleasant smell (e.g., earthy or nutty), no immediate adverse reactions |

| Seasonal Growth | Poisonous mushrooms often appear after rain in autumn and winter; edible species vary by season |

| Habitat | Poisonous mushrooms commonly found in gardens, lawns, and woodlands; edible species often near specific trees (e.g., pine, eucalyptus) |

| Spore Color | Poisonous: White or colorless; Edible: Brown, purple, or black (check with spore print test) |

| Legal Advice | Do not consume wild mushrooms without expert identification; contact local mycological societies or poison control (Australia: 13 11 26) |

| Regional Variations | Toxicity varies by region; always consult local guides or experts for accurate identification |

| Prevention Tips | Avoid touching or ingesting unknown mushrooms; teach children and pets to stay away from wild fungi |

Explore related products

$18.32 $35

What You'll Learn

Common poisonous mushrooms in Australia

Australia's diverse fungal landscape includes several species that can pose a serious health risk if ingested. Among the most notorious is the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*), a sleek, greenish-hilled mushroom often found near oak trees. Its innocuous appearance belies its deadly nature: consuming just 50 grams can be fatal to an adult, and symptoms may not appear until 6–24 hours after ingestion, making it particularly treacherous. Unlike many poisonous mushrooms, the Death Cap doesn’t cause immediate discomfort, leading victims to delay seeking medical help. If you suspect ingestion, immediate hospitalisation is critical, as liver and kidney failure can occur within days.

Another culprit lurking in Australian backyards is the Satin Gecko (*Chlorociboria aeruginosa*), identifiable by its vibrant blue-green cap. While not typically lethal, it contains toxins that cause severe gastrointestinal distress, including vomiting, diarrhoea, and abdominal pain. Children and pets are particularly vulnerable due to their lower body mass, and even small amounts can lead to dehydration. To prevent accidental poisoning, teach children the mantra, “If you’re not 100% sure, don’t touch or taste,” and keep pets on a leash in areas where mushrooms grow.

Foraging enthusiasts should also beware of the Fool’s Webcap (*Cortinarius rubellus*), a deceptively ordinary-looking mushroom with a brown cap and web-like veil remnants. Its toxins target the kidneys, causing symptoms like thirst, frequent urination, and muscle cramps within 2–6 days. Unlike the rapid onset of Death Cap poisoning, the Fool’s Webcap’s effects are insidious, often mistaken for flu or dehydration. If you’re an amateur forager, avoid brown-capped mushrooms altogether, as many toxic species resemble edible varieties.

A comparative analysis of these three species highlights the importance of accurate identification. While the Death Cap and Fool’s Webcap share a brownish hue, the former’s greenish tint and bulbous base distinguish it. The Satin Gecko, on the other hand, stands out with its vivid colouration, but its small size makes it easy to overlook. Investing in a reliable field guide or consulting a mycologist can save lives, as even experienced foragers can misidentify mushrooms under certain conditions.

In conclusion, Australia’s poisonous mushrooms demand respect and caution. Practical steps include wearing gloves when handling unknown fungi, avoiding areas with dense mushroom growth, and documenting the appearance of any suspicious species in your yard. Remember, no mushroom is worth risking your health—when in doubt, throw it out. By staying informed and vigilant, you can safely coexist with these fascinating yet potentially dangerous organisms.

Brittlestem Mushrooms and Dogs: Are They a Toxic Danger?

You may want to see also

Identifying safe vs. toxic mushrooms

In Australia, where over 5,000 mushroom species thrive, distinguishing between safe and toxic varieties is a matter of life and death. The deadly Death Cap (Amanita phalloides), for instance, resembles the edible Straw Mushroom (Volvariella volvacea) but contains amatoxins that can cause liver failure within 48 hours. Always assume a mushroom is poisonous unless positively identified by an expert.

Identification begins with observation. Note the mushroom’s cap shape, color, and texture; gill arrangement; stem features; and whether it has a ring or volva (a cup-like base). Toxic mushrooms often have white gills and a bulbous base, like the Death Cap, while edible ones, such as the Field Mushroom (Agaricus campestris), typically have pinkish gills and a smooth stem. However, relying solely on color or appearance is risky—some toxic species mimic edible ones closely.

Foraging safely requires a multi-step approach. First, consult field guides specific to Australian fungi, such as *Fungi Down Under* by Neale B. Walsh. Second, use spore prints to determine color, a key identifier. Place the cap on paper overnight; toxic species like the Poison Fire Coral (Podostroma cornu-damae) produce orange spores, while edible ones like the Slippery Jack (Suillus luteus) produce brown. Third, avoid mushrooms growing near polluted areas, as they can accumulate toxins.

Children and pets are particularly vulnerable. Teach kids never to touch or taste wild mushrooms, and keep pets leashed in mushroom-prone areas. If ingestion occurs, seek immediate medical attention. The Australian Poisons Information Centre (13 11 26) provides critical advice, and bringing a sample of the mushroom can aid identification and treatment.

Ultimately, the safest approach is to avoid wild mushroom consumption altogether. Cultivated varieties from reputable sources eliminate risk. For those determined to forage, join a local mycological society for hands-on learning. Remember, no single rule guarantees safety—only expert knowledge and caution can protect against Australia’s toxic fungi.

Are Stinkhorn Mushrooms Poisonous? Unveiling the Truth About This Odd Fungus

You may want to see also

Symptoms of mushroom poisoning

Mushroom poisoning symptoms can appear anywhere from 20 minutes to 24 hours after ingestion, depending on the type of toxin involved. Rapid-onset symptoms, typically caused by mushrooms like the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*), include severe abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea within 6–24 hours. These symptoms may temporarily subside, giving a false sense of recovery, but organ damage progresses silently. Delayed-onset symptoms, seen with species like the Funeral Bell (*Galerina marginata*), take 6–24 hours to manifest as gastrointestinal distress, followed by liver and kidney failure. Knowing the timeline is critical: immediate medical attention is required if poisoning is suspected, even if symptoms seem mild.

Symptoms vary widely based on the mushroom’s toxin. Gastrointestinal symptoms—nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain—are common across many poisonous species, including the Yellow Stainer (*Agaricus xanthodermus*). Neurological symptoms, such as hallucinations, confusion, or seizures, are characteristic of psychoactive mushrooms like the Blue Meanie (*Psilocybe subaeruginosa*), though these are less dangerous than organ toxins. Organ failure symptoms, such as jaundice, dark urine, or bruising, indicate severe poisoning from mushrooms like the Death Cap. Children are particularly vulnerable due to their lower body weight, and even small amounts can be fatal. Always note the mushroom’s appearance and time of ingestion to aid diagnosis.

If poisoning is suspected, immediate action is vital. Call emergency services or a poison control center, providing details of the mushroom and symptoms. Do not induce vomiting unless advised by a professional, as it can worsen certain types of poisoning. Activated charcoal may be administered in a hospital setting to reduce toxin absorption, but this is not a home remedy. In severe cases, liver transplants have been necessary for survival, particularly with Death Cap poisoning. Keep a sample of the mushroom for identification, but do not touch it without gloves, as some toxins can be absorbed through the skin.

Prevention is the best defense. Avoid foraging unless you are an experienced mycologist, as many poisonous mushrooms resemble edible varieties. Teach children not to touch or eat wild mushrooms, and keep pets away from unfamiliar fungi. If you suspect mushrooms in your yard are poisonous, remove them carefully, disposing of them in sealed bags to prevent pets or wildlife from ingesting them. Remember, no simple rule—like color or smell—can reliably identify a poisonous mushroom. When in doubt, assume it’s toxic and leave it alone.

Identifying Poisonous Mushrooms: Essential Tips for Safe Foraging and Consumption

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Safe mushroom foraging tips

Mushrooms in Australian backyards can be as intriguing as they are dangerous, with over 5,000 species recorded and only a fraction well-documented. Identifying safe varieties requires more than a casual glance; it demands a systematic approach. Start by noting the mushroom’s habitat—is it growing on wood, soil, or manure? This detail alone can narrow down potential species. For instance, the common *Agaricus campestris* (field mushroom) thrives in grassy areas, while the toxic *Amanita* species often appear near eucalyptus trees. Cross-reference your findings with reliable field guides or apps like *FungiMap Australia*, but remember: visual identification is an art, not a science.

One critical rule in safe foraging is the "cut and observe" method. Slice the mushroom in half and note its color changes, if any. For example, the edible *Lactarius deliciosus* (Saffron Milk Cap) exudes a distinctive orange-red latex when cut, while the deadly *Galerina marginata* may show no immediate reaction. Time is key—some toxic species, like the *Amanita phalloides* (Death Cap), take hours to change color. Always carry a small notebook to record these observations, as they can be crucial for later verification. Avoid tasting or touching mushrooms directly, as some toxins can be absorbed through the skin.

Children and pets are particularly vulnerable to mushroom poisoning, with symptoms ranging from mild gastrointestinal distress to organ failure. If foraging with kids, educate them on the "look but don’t touch" rule and emphasize that colorful or fragrant mushrooms are not always safe. In Australia, the *Amanita muscaria* (Fly Agaric), with its iconic red cap and white spots, is often mistaken for a fairy tale mushroom but can cause hallucinations and seizures if ingested. Keep a pet-safe deterrent spray handy to discourage curious animals from sampling backyard fungi.

Foraging should never be a solo endeavor, especially for beginners. Join local mycological societies or guided walks to learn from experienced foragers. These groups often provide hands-on training in spore printing, a technique where the mushroom’s gills are placed on paper to reveal spore color—a key identification feature. For instance, the edible *Boletus edulis* (Porcini) has brown spores, while the toxic *Cortinarius* species produce rusty-brown spores. Practice this method at home with collected samples, but always double-check with experts before consuming.

Finally, when in doubt, throw it out. No meal is worth the risk of poisoning. Australian hospitals report over 300 mushroom-related cases annually, many from misidentified backyard species. If ingestion occurs, call the Poisons Information Centre (13 11 26) immediately, providing a detailed description or photo of the mushroom. Time is critical, as symptoms from toxic species like the *Amanita ocreata* (Destroying Angel) can take 6–24 hours to appear, leading to false complacency. Safe foraging is a blend of knowledge, caution, and respect for nature’s complexity.

Are Brown Hay Mushrooms Poisonous to Dogs? Essential Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Local experts and resources for identification

Identifying whether the mushrooms in your yard are poisonous requires more than a quick Google search. Local experts and resources are invaluable for accurate identification, especially in Australia, where unique species like the deadly Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*) can appear in suburban gardens. Mycologists—scientists specializing in fungi—often offer consultations or workshops. For instance, the Australian National Botanic Gardens in Canberra hosts fungi identification sessions during autumn, where experts analyze samples brought by the public. Similarly, state-based mycological societies, such as the Queensland Mycological Society, provide forums and field days where amateurs can learn from seasoned identifiers.

If in-person resources are unavailable, online platforms like iNaturalist Australia allow users to upload photos of mushrooms for community identification. While not foolproof, these platforms often attract local experts who can provide insights. However, caution is essential; online identifications should always be cross-referenced with authoritative sources. The Fungimap database, a citizen science initiative, is another tool for comparing your findings against documented Australian species. For urgent cases, contacting your local poison control center or a hospital is critical—they can provide immediate advice if ingestion is suspected.

For hands-on learners, field guides specific to Australian fungi are indispensable. Titles like *Fungi of Australia* by Neale B. Walsh and *A Field Guide to Australian Fungi* by Bruce A. Fuhrer include detailed descriptions, photographs, and toxicity notes. These guides often categorize mushrooms by habitat, making it easier to narrow down possibilities based on your yard’s environment. Pairing a guide with a magnifying glass and a notebook for observations can turn identification into a methodical process, though it’s crucial to avoid handling mushrooms without gloves, as some species can cause skin irritation.

Schools and community centers occasionally host workshops led by local experts, offering practical tips like checking for spore color (a key identification feature) or noting the mushroom’s smell. For example, the Death Cap has a distinct honey-like odor, while the edible Saffron Milk Cap (*Lactarius deliciosus*) exudes a milky sap. Such workshops often emphasize the “if in doubt, throw it out” rule, as even experienced foragers avoid mushrooms they cannot confidently identify. Engaging with these resources not only ensures safety but also deepens your understanding of Australia’s diverse fungal ecosystems.

Are Polypore Mushrooms Poisonous? A Comprehensive Guide to Safety

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Identifying poisonous mushrooms in Australia requires careful observation of features like color, shape, gills, and spore print. However, many species look similar, and some toxic mushrooms resemble edible ones. It’s safest to consult a mycologist or use a reliable field guide specific to Australian fungi.

Yes, some toxic mushrooms in Australia include the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*), which is highly poisonous and often found near oak trees, and the Funeral Bell (*Galerina marginata*), which resembles harmless brown mushrooms. Always avoid consuming wild mushrooms unless identified by an expert.

Most mushrooms in Australia are not harmful to touch or smell, but it’s best to avoid direct contact, especially if you have sensitive skin or allergies. Some species can cause irritation, and ingesting even a small amount of a toxic mushroom can be dangerous.

If you suspect ingestion of a mushroom, seek immediate medical or veterinary attention. Take a sample of the mushroom (if safe) or a photo for identification. Do not wait for symptoms to appear, as some toxic mushrooms can cause severe reactions quickly.