Wild mushrooms are a fascinating yet potentially dangerous subject for foragers and nature enthusiasts. While many species are edible and prized for their unique flavors, others contain toxins that can cause severe illness or even be fatal if consumed. Identifying wild mushrooms accurately is crucial, as some poisonous varieties closely resemble their safe counterparts. Common toxic species include the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*) and the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*), which are responsible for the majority of mushroom-related fatalities. Symptoms of poisoning can range from gastrointestinal distress to organ failure, depending on the type of toxin ingested. Therefore, it is strongly recommended to consult expert guides or mycologists and avoid consuming wild mushrooms unless absolutely certain of their safety.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Prevalence of Poisonous Species | Approximately 2-10% of wild mushroom species are toxic to humans. |

| Common Toxic Compounds | Amatoxins (e.g., alpha-amanitin), orellanine, muscarine, psilocybin, and coprine. |

| Symptoms of Poisoning | Gastrointestinal (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea), neurological (hallucinations, seizures), liver/kidney failure, or cardiovascular issues, depending on the toxin. |

| Deadly Species Examples | Death Cap (Amanita phalloides), Destroying Angel (Amanita bisporigera), and Fool's Mushroom (Amanita verna). |

| Edible Look-Alikes | Many toxic mushrooms resemble edible species (e.g., Death Cap vs. Paddy Straw Mushroom). |

| Safe Identification Methods | Requires expert knowledge, field guides, and sometimes chemical tests; never rely solely on folklore or visual cues. |

| Geographic Distribution | Toxic species are found worldwide, with regional variations in prevalence. |

| Seasonal Risk | Most poisonings occur in late summer and fall when mushroom growth peaks. |

| Treatment for Poisoning | Immediate medical attention, activated charcoal, and, in severe cases, liver transplants or antidotes like silibinin. |

| Prevention Tips | Avoid consuming wild mushrooms unless identified by an expert, cook thoroughly, and avoid alcohol when consuming mushrooms. |

Explore related products

$7.62 $14.95

What You'll Learn

Common poisonous species identification

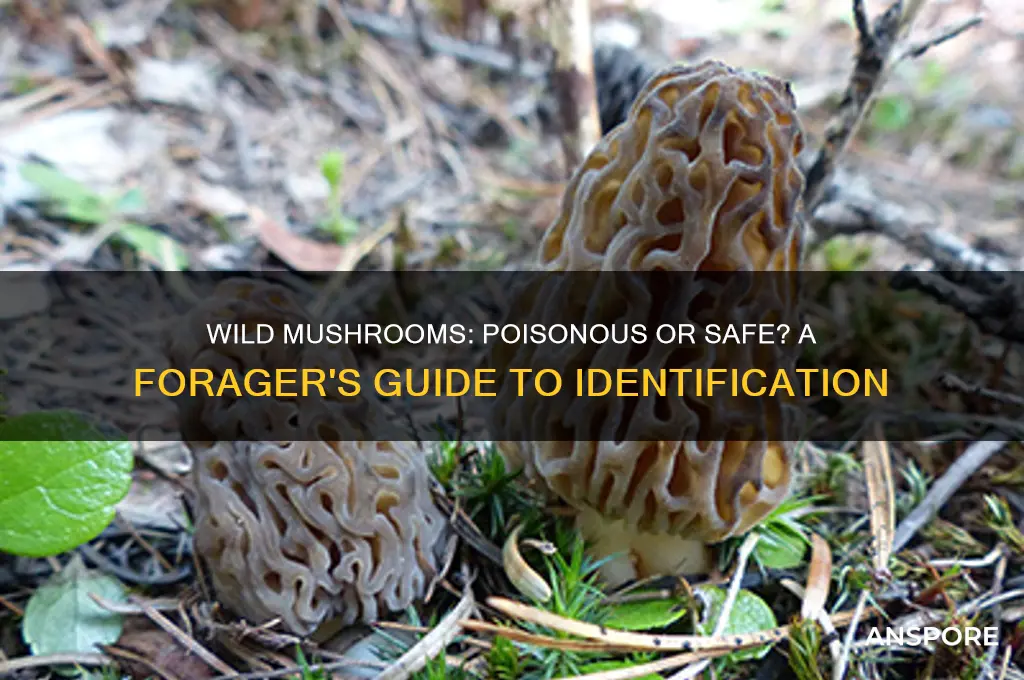

Wild mushrooms are a fascinating yet perilous subject for foragers. While many species are safe and even delicious, others can cause severe illness or death. Identifying poisonous mushrooms requires knowledge of specific traits and species. Here’s a focused guide to recognizing some of the most dangerous ones.

The Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*) is arguably the most notorious poisonous mushroom. Its olive-green cap and white gills may resemble edible varieties, but it contains amatoxins, which cause liver and kidney failure. Symptoms appear 6–24 hours after ingestion, starting with vomiting and diarrhea, followed by potential organ collapse. A single mushroom contains enough toxin to kill an adult. Key identifiers include a bulbous base, a skirt-like ring on the stem, and a musty odor. Avoid any mushroom with these traits unless positively identified by an expert.

In contrast, the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*) is pure white, often misleading novice foragers into thinking it’s safe. Its amatoxins are equally deadly, and its symptoms mirror those of the Death Cap. This species lacks the green hues of its cousin but shares the bulbous base and ring. Its pristine appearance belies its lethal nature, making it a prime example of why color alone is insufficient for identification. Always scrutinize structural features before consuming any wild mushroom.

False Morel (*Gyromitra esculenta*) is another deceptive species, often mistaken for true morels due to its brain-like, wrinkled cap. However, it contains gyromitrin, which breaks down into a toxic compound similar to rocket fuel. Cooking reduces but does not eliminate the toxin, and symptoms include gastrointestinal distress, dizziness, and seizures. Fatalities are rare but possible, especially in children or with repeated exposure. True morels have a hollow, sponge-like structure, while false morels are often chambered or cottony inside. When in doubt, discard.

Conocybe filaris, known as the Deadly Conocybe, is less conspicuous but equally dangerous. This small, tan mushroom grows in lawns and gardens, often overlooked until it’s too late. It contains the same amatoxins as the Death Cap and Destroying Angel, with symptoms appearing within hours. Its unassuming appearance—a bell-shaped cap and thin stem—makes it easy to mistake for harmless varieties. Always avoid small, nondescript mushrooms in urban areas, especially if children or pets are present.

To safely forage, follow these steps: 1) Learn the key features of poisonous species, 2) carry a reliable field guide or app, 3) never eat a mushroom unless 100% certain of its identity, and 4) consult an expert when unsure. Remember, no single trait—color, habitat, or odor—guarantees safety. Poisonous mushrooms often mimic edible ones, making meticulous identification essential. Your life could depend on it.

Understanding Mushroom Poisoning: Symptoms, Risks, and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Symptoms of mushroom poisoning in humans

Wild mushrooms can be a culinary delight, but their allure often masks a dangerous reality. Many species contain toxins that, when ingested, can lead to severe health complications or even death. Recognizing the symptoms of mushroom poisoning is crucial for prompt treatment and recovery. These symptoms vary widely depending on the type of toxin involved, the amount consumed, and the individual’s health. Early detection can be the difference between a mild illness and a life-threatening emergency.

Symptoms typically appear within 20 minutes to 4 hours after ingestion, though some toxins may take up to 24 hours to manifest. Gastrointestinal distress—nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain—is among the most common early signs. These symptoms often mimic food poisoning, making diagnosis challenging without a clear history of mushroom consumption. For instance, amatoxins found in *Amanita* species cause severe liver damage, but initial symptoms may seem benign, delaying critical medical intervention.

Neurological symptoms are another red flag, particularly with mushrooms containing muscarine or psilocybin. Muscarine poisoning, often from *Clitocybe* or *Inocybe* species, causes excessive sweating, salivation, tearing, and blurred vision, sometimes within 15–30 minutes of ingestion. Psilocybin mushrooms, while less toxic, can induce hallucinations, confusion, and anxiety, which may be mistaken for a psychiatric episode. In children, even small doses of certain toxins can lead to rapid dehydration or respiratory failure, making immediate medical attention essential.

Cardiac symptoms, such as irregular heartbeat or low blood pressure, may occur with mushrooms containing toxins like coprine or gyromitrin. Coprine, found in *Coprinus* species, causes a "disulfiram-like" reaction when alcohol is consumed within 72 hours of ingestion, leading to flushing, nausea, and palpitations. Gyromitrin, present in *Gyromitra* species, can cause seizures, jaundice, and even coma in severe cases. These symptoms often require hospitalization and supportive care, including activated charcoal administration or liver transplant in extreme cases.

Prevention is the best defense against mushroom poisoning. Avoid consuming wild mushrooms unless identified by a trained mycologist. If poisoning is suspected, note the mushroom’s appearance, save a sample for identification, and contact a poison control center immediately. Early intervention, including gastric decontamination and antidote administration, can significantly improve outcomes. Remember, the absence of immediate symptoms does not guarantee safety—some toxins act insidiously, making vigilance paramount.

Are Toadstool Mushrooms Poisonous? Unveiling the Truth Behind the Myth

You may want to see also

Safe wild mushroom foraging tips

Wild mushrooms are a culinary treasure, but their allure comes with a stark warning: many are toxic, and some fatally so. Misidentification is the primary risk, as edible and poisonous species often resemble each other. For instance, the deadly Amanita phalloides (Death Cap) closely mimics the edible Paddy Straw mushroom, differing only in subtle features like spore color and gill attachment. This underscores the critical need for precise knowledge and caution in foraging.

To forage safely, start by educating yourself thoroughly. Invest in reputable field guides like *Mushrooms Demystified* by David Arora or enroll in a mycology course. Learn the key identification features: cap shape, gill structure, spore print color, and habitat. For example, the spore print of an Amanita is white, while a Lactarius species produces a milky fluid when cut. Always cross-reference findings with multiple sources, and never rely solely on apps or online images, which can be misleading.

Field practices must prioritize caution. Carry a knife and basket (not a plastic bag, which can cause spoilage) and harvest only specimens in pristine condition. Avoid mushrooms growing near roadsides or industrial areas due to potential contamination. Take detailed notes or photographs of each find, including its habitat, to aid identification later. If unsure, discard the specimen—no meal is worth the risk.

Even with careful identification, some toxic mushrooms require additional steps to render them safe. For example, the edible *Lactarius deliciosus* must be thoroughly cooked to remove its mild toxins. Conversely, the *Morchella* (morel) should be cooked to eliminate gastrointestinal irritants. Never consume raw wild mushrooms, and always cook them well. If experimenting with a new species, start with a small portion and wait 24 hours to check for adverse reactions.

Finally, adopt a mindset of humility and respect for nature. Even experienced foragers make mistakes, and the consequences can be severe. Join local mycological societies to learn from seasoned experts and participate in group forays. Document your finds and contribute to citizen science projects to deepen your understanding. Remember, the goal is not just to harvest mushrooms but to cultivate a sustainable, safe practice that honors both the ecosystem and your health.

Are Mowers Mushrooms Poisonous to Dogs? Risks and Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Differences between toxic and edible varieties

Wild mushrooms present a fascinating yet perilous duality: some are culinary treasures, while others are deadly poisons. Distinguishing between toxic and edible varieties requires keen observation and knowledge, as superficial similarities often belie profound differences. For instance, the Amanita muscaria, with its vibrant red cap and white spots, resembles the edible fly agaric to the untrained eye, but the former can cause severe hallucinations and organ damage. Conversely, the chanterelle’s golden, forked ridges and fruity aroma mark it as a safe and prized delicacy. This contrast underscores the critical need to understand specific traits that differentiate the benign from the lethal.

One of the most reliable methods to identify edible mushrooms is to examine their physical characteristics systematically. Edible varieties often exhibit consistent features such as gills that attach broadly to the stem (like in shiitakes) or pores instead of gills (like in boletes). Toxic mushrooms, however, may have fragile, free gills or a skirt-like ring on the stem, as seen in many Amanita species. Additionally, edible mushrooms typically lack a distinct, unpleasant odor, while toxic ones may smell of raw potatoes, garlic, or even chlorine. For example, the edible oyster mushroom has a subtle anise scent, whereas the toxic death cap emits a faint, sweet odor that belies its extreme toxicity.

Beyond visual and olfactory cues, understanding the habitat and seasonality of mushrooms is crucial. Edible varieties like morels thrive in specific conditions, such as deciduous forests in spring, while toxic species like the destroying angel often appear in similar environments but can be distinguished by their pure white coloration and bulbous base. A practical tip is to document the location and time of year when harvesting, as this data can help verify the mushroom’s identity. For instance, if you find a mushroom in a coniferous forest in autumn, it’s less likely to be a spring-specific morel and warrants extra scrutiny.

Finally, when in doubt, err on the side of caution. Even experienced foragers consult field guides or apps like iNaturalist for verification. A single toxic mushroom can contain enough amatoxins to cause liver failure within 24–48 hours, with symptoms initially mimicking food poisoning. Children and pets are particularly vulnerable due to their lower body mass, so keep foraged mushrooms out of their reach. If ingestion of a potentially toxic mushroom occurs, seek medical attention immediately, bringing a sample for identification. Remember, no taste test or folklore remedy can reliably determine edibility—only precise knowledge and verification can safeguard against the hidden dangers of the wild.

Spotting Deadly Fungi: A Guide to Identifying Poisonous Mushrooms Safely

You may want to see also

Treatment for accidental mushroom ingestion

Wild mushrooms can be a hidden danger in nature, with many species resembling edible varieties but containing toxins that can cause severe illness or even death. Accidental ingestion requires immediate action, as symptoms can range from mild gastrointestinal discomfort to life-threatening organ failure. The first step is to remain calm but act swiftly, as time is critical in minimizing the effects of mushroom poisoning.

Identification and Documentation: If possible, collect a sample of the mushroom or take a clear photograph before removing it from the site. This aids in identification by medical professionals or mycologists, who can determine the species and its potential toxicity. Note the time of ingestion, the amount consumed, and any symptoms experienced. For children or pets, estimate the quantity based on the size of the mushroom and the number missing from the patch. This information is crucial for healthcare providers to assess the severity of the poisoning and tailor treatment accordingly.

Immediate Actions: Contact your local poison control center or emergency services immediately. In the U.S., the Poison Help Line (1-800-222-1222) provides expert advice 24/7. Do not induce vomiting unless instructed by a professional, as some toxins can cause further damage when regurgitated. If the person is unconscious, experiencing seizures, or having difficulty breathing, administer first aid and prepare for emergency transport. For mild symptoms, such as nausea or diarrhea, monitor closely and seek medical attention if symptoms worsen or persist.

Medical Treatment: Treatment varies depending on the type of mushroom and the severity of poisoning. For Amanita phalloides (Death Cap) or similar toxic species, hospitalization is often necessary. Activated charcoal may be administered to bind toxins in the gastrointestinal tract, reducing absorption. In severe cases, intravenous fluids, electrolytes, and medications to protect the liver or kidneys may be required. For hallucinogenic mushrooms, such as Psilocybe species, treatment focuses on managing psychological symptoms, including anxiety, agitation, or hallucinations. Sedatives or antipsychotics may be used in extreme cases, but most individuals recover without long-term effects.

Prevention and Education: The best treatment is prevention. Educate yourself and others about the risks of wild mushroom foraging. Teach children and pets to avoid touching or eating unknown fungi. When in doubt, consult a mycologist or use reliable field guides. If you suspect poisoning, act quickly and provide detailed information to healthcare providers. Remember, not all wild mushrooms are poisonous, but the consequences of misidentification can be severe. Stay informed, stay cautious, and enjoy nature’s wonders safely.

Are Toadstools Poisonous? Unveiling the Truth About Fungal Toxicity

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all wild mushrooms are poisonous. Many are edible and safe to consume, but it’s crucial to properly identify them, as some toxic species closely resemble edible ones.

There is no single rule to determine if a wild mushroom is poisonous. Characteristics like color, gills, or bruising are not reliable indicators. Always consult a mycologist or use a trusted field guide for identification.

Seek medical attention immediately, even if symptoms haven’t appeared. Bring a sample of the mushroom or a photo for identification to help with treatment.

Yes, some common poisonous mushrooms include the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*), Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*), and Conocybe species. Avoid consuming any wild mushrooms unless you are absolutely certain of their identity.