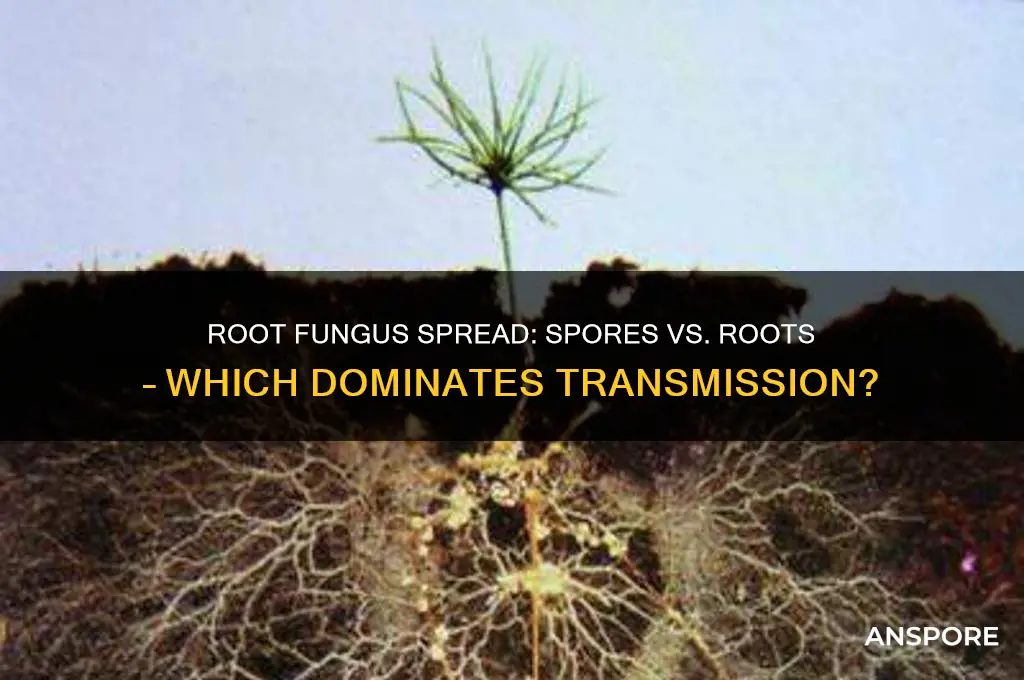

Root fungi, such as those in the *Armillaria* genus, are known to spread through dual mechanisms: spores and vegetative growth via their mycelial networks. Spores, produced on fruiting bodies like mushrooms, can be dispersed by wind, water, or animals, allowing the fungus to colonize new areas. Simultaneously, these fungi extend their root-like structures, called rhizomorphs, through the soil to infect adjacent plants directly. This dual strategy enables them to efficiently propagate both locally and over longer distances, making them significant pathogens in forest ecosystems and agricultural settings. Understanding how root fungi utilize both spores and roots for spread is crucial for managing their impact on plant health and ecosystem dynamics.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Spread by Spores | Yes, many root fungi produce spores that can be dispersed by wind, water, or insects, allowing them to infect new plants. |

| Spread by Roots | Yes, root fungi can spread through direct root-to-root contact, especially in closely planted or interconnected root systems. |

| Types of Spores | Various types, including asexual spores (e.g., conidia) and sexual spores (e.g., ascospores, basidiospores), depending on the fungal species. |

| Infection Mechanisms | Spores germinate and penetrate plant roots, while root-to-root spread occurs via hyphae (filamentous structures) growing from infected to healthy roots. |

| Environmental Factors | Spread is influenced by soil moisture, temperature, and pH, which affect spore germination and hyphal growth. |

| Host Range | Varies by species; some fungi are specific to certain plant species, while others are generalists. |

| Symptoms | Root rot, stunted growth, wilting, yellowing leaves, and reduced yield, depending on the fungus and host plant. |

| Management | Practices include crop rotation, resistant plant varieties, fungicides, and maintaining proper soil drainage to reduce fungal spread. |

| Examples of Fungi | Armillaria (honey fungus), Rhizoctonia, Fusarium, and Phytophthora. |

| Economic Impact | Significant losses in agriculture and forestry due to reduced crop yields and tree mortality. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Spores: Dispersal mechanisms

Root fungi, particularly those forming mycorrhizal associations, often rely on spores as a primary dispersal mechanism. Spores are microscopic, lightweight structures produced in vast quantities, enabling fungi to colonize new environments efficiently. Unlike seeds, spores require minimal energy investment, making them an economical strategy for fungi to propagate over large areas. This method is particularly crucial for root fungi, as it allows them to establish symbiotic relationships with plants in diverse ecosystems, from forests to grasslands.

Consider the dispersal mechanisms of spores, which are as varied as they are ingenious. Wind dispersal, or anemochory, is one of the most common methods. Spores are often equipped with structures like wings or threads, increasing their surface area and allowing them to travel significant distances on air currents. For example, the spores of *Armillaria*, a root-rotting fungus, are released in large quantities and can be carried kilometers away, facilitating rapid colonization of new root systems. This mechanism is especially effective in open environments where wind flow is unimpeded.

Water also plays a critical role in spore dispersal, particularly for fungi in aquatic or moist environments. Spores released into water can be transported downstream, colonizing new areas along riverbanks or soil surfaces. This is evident in *Phytophthora*, a water mold that causes root rot in plants. Its spores, known as zoospores, are motile and can swim through water films in soil, ensuring efficient spread even in saturated conditions. This adaptability highlights the fungus’s ability to exploit multiple dispersal pathways depending on environmental conditions.

Animals and humans inadvertently contribute to spore dispersal, a process known as zoochory. Spores can adhere to fur, feathers, or footwear and be transported to new locations. For instance, mycorrhizal fungi like *Amanita* species produce spores that attach to the feet of foraging animals, facilitating their spread across forest floors. Similarly, human activities such as gardening or logging can disturb soil, releasing spores into the air or onto tools, which then carry them to new sites. This underscores the importance of hygiene practices, such as cleaning equipment, to prevent unintended fungal spread.

Understanding these dispersal mechanisms is crucial for managing fungal diseases in agriculture and forestry. For example, reducing soil disturbance and maintaining windbreaks can limit spore dispersal in crop fields. In greenhouse settings, controlling humidity and airflow can minimize the spread of waterborne spores. By targeting these mechanisms, growers can mitigate the impact of root fungi and protect plant health. This knowledge also informs conservation efforts, as mycorrhizal fungi play vital roles in nutrient cycling and ecosystem stability.

Are Potato Spores Poisonous? Uncovering the Truth About Potato Safety

You may want to see also

Root-to-root transmission pathways

To understand the dynamics of root-to-root transmission, consider the role of mycorrhizal networks. These symbiotic associations between fungi and plant roots can inadvertently facilitate pathogen spread. In a mycorrhizal network, nutrients and signals are exchanged between plants, but so are pathogens like *Phytophthora* or *Rhizoctonia*. For instance, a study in *Nature Communications* (2019) demonstrated that *Phytophthora cinnamomi* exploited mycorrhizal networks in Australian eucalypt forests, moving from infected to healthy trees without aboveground contact. This highlights the dual nature of mycorrhizae: beneficial for nutrient uptake but potentially harmful as conduits for disease.

Preventing root-to-root transmission requires targeted strategies. One practical approach is maintaining root separation through physical barriers, such as geotextiles or gravel layers, in agricultural settings. For home gardeners, spacing plants appropriately and avoiding overcrowding can reduce the likelihood of root contact. Additionally, soil solarization—heating soil to 50–60°C for 4–6 weeks—can kill fungal structures in the root zone, though this method is more feasible for small-scale applications. Chemical interventions, like fungicidal soil drenches containing thiophanate-methyl or propamocarb, can also disrupt root-to-root pathways, but their efficacy depends on proper timing and dosage.

Comparatively, root-to-root transmission contrasts with spore-based spread in its stealth and persistence. While spores are easily detected and managed through sanitation or fungicides, root-to-root pathways operate unseen, often leading to latent infections. For example, *Verticillium wilt* can remain dormant in a plant’s vascular system for years before symptoms appear, all while spreading to neighboring plants via shared roots. This underscores the need for proactive soil health management, including crop rotation and resistant cultivars, to break the transmission cycle.

In conclusion, root-to-root transmission pathways represent a sophisticated yet underappreciated mode of fungal spread. By understanding the mechanisms—whether through rhizomorphs, mycorrhizal networks, or latent infections—growers can implement targeted interventions to mitigate risk. While spore-based spread often dominates discussions of fungal diseases, the subterranean movement of pathogens demands equal attention, particularly in perennial crops and natural ecosystems where root systems are densely interconnected.

Are Shroom Spores Legal in Florida? Understanding the Current Laws

You may want to see also

Environmental factors aiding spread

Root fungi, such as *Armillaria* (honey fungus) and *Rhizoctonia*, exploit environmental conditions to spread via spores and root systems. Moisture is a critical factor; high humidity and damp soil create ideal conditions for spore germination and mycelial growth. For instance, *Armillaria* spores require a water film to adhere to surfaces and initiate infection. In regions with annual rainfall exceeding 500 mm, the spread of these fungi accelerates, particularly in poorly drained soils. Gardeners and farmers should monitor soil moisture levels, ensuring proper drainage to mitigate this risk.

Temperature plays a dual role in fungal proliferation. Most root fungi thrive in moderate temperatures (15–25°C), which stimulate spore production and root colonization. However, extreme temperatures can suppress their activity. For example, *Fusarium* species, which spread via roots and spores, are less active below 10°C. In temperate climates, spring and autumn provide optimal conditions for their spread. To counteract this, crop rotation and soil solarization (heating soil to 50°C for 4–6 weeks) can disrupt fungal life cycles.

Soil composition and pH significantly influence fungal dispersal. Fungi like *Phytophthora* prefer acidic soils (pH 4.5–6.0), where they can more easily colonize roots and release spores. In contrast, alkaline soils (pH 7.5–8.5) inhibit many root fungi. Amending soil with lime to raise pH can reduce fungal populations, but this must be balanced with crop requirements. Additionally, compacted soils restrict root growth, forcing plants to grow closer together, which facilitates root-to-root fungal transmission. Regular tilling and organic matter incorporation improve soil structure, reducing this risk.

Vegetation density and plant health are environmental factors often overlooked. Overcrowded plants create microclimates of high humidity and limited airflow, fostering spore dispersal. Weakened or stressed plants, due to drought or nutrient deficiency, are more susceptible to root fungi. For example, *Rhizoctonia* targets plants with nitrogen deficiencies, as these have thinner cell walls. Maintaining optimal plant spacing (e.g., 30–45 cm between seedlings) and applying balanced fertilizers (10–10–10 NPK ratio) can enhance plant resilience and limit fungal spread.

Human activities inadvertently aid fungal dispersal. Contaminated tools, footwear, and irrigation water can transport spores and infected root fragments across gardens or fields. For instance, *Armillaria* spores can survive on pruning shears for up to 48 hours. Sanitizing tools with a 10% bleach solution before use and avoiding working in wet conditions can prevent cross-contamination. Similarly, using untreated water for irrigation may introduce fungal pathogens, emphasizing the need for filtration or UV treatment systems in high-risk areas.

Do All Clostridium Species Form Spores? Unraveling the Truth

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Host plant susceptibility roles

Root fungi, such as *Armillaria* and *Rhizoctonia*, exploit host plant susceptibility to spread via spores and roots. Susceptibility is not uniform; it varies based on plant species, age, and physiological state. For instance, young seedlings often lack the robust defense mechanisms of mature plants, making them more vulnerable to fungal colonization. Similarly, stressed plants—those suffering from drought, nutrient deficiency, or mechanical damage—exhibit weakened root systems that fungi readily exploit. Understanding these susceptibility factors is critical for developing targeted management strategies.

To mitigate fungal spread, assess host plant health systematically. Start by evaluating soil conditions, as poor drainage or compacted soil can stress roots and increase susceptibility. Apply organic amendments like compost to improve soil structure and nutrient availability. For young plants, create a protective barrier using fungicidal treatments or biological agents like *Trichoderma*, which compete with pathogenic fungi. Monitor plants regularly for early signs of stress, such as wilting or yellowing leaves, and address underlying issues promptly.

Comparatively, resistant plant varieties offer a proactive solution to reduce fungal spread. For example, certain tomato cultivars exhibit genetic resistance to *Fusarium* wilt, a root fungus that spreads via spores and roots. When selecting plants, prioritize disease-resistant varieties suited to your climate and soil type. Crop rotation is another effective strategy, as it disrupts fungal life cycles by depriving them of susceptible hosts. Avoid planting the same crop family in the same area for consecutive seasons to minimize soil-borne pathogen buildup.

A persuasive argument for integrated pest management (IPM) highlights its role in reducing host plant susceptibility. IPM combines cultural, biological, and chemical methods to create an environment hostile to root fungi. For instance, intercropping with non-host plants can reduce fungal spore dispersal, while beneficial nematodes target fungal mycelium in the soil. Chemical fungicides should be used sparingly and only when necessary, as overuse can lead to resistance. By diversifying control methods, you decrease reliance on any single approach, ensuring long-term effectiveness.

Finally, descriptive insights into fungal behavior underscore the importance of host susceptibility. Root fungi often form extensive networks, or mycorrhizae, that connect multiple plants, facilitating nutrient exchange and pathogen spread. In susceptible hosts, these networks act as highways for spores and root fragments, accelerating infection. Breaking these connections through physical barriers, such as root-proof membranes, can limit fungal movement. Additionally, maintaining optimal plant spacing reduces root-to-root contact, further curtailing spread. By focusing on host susceptibility, you can disrupt fungal pathways and protect your plants effectively.

Psilocybe Cubensis Spores in Texas: Legal Status Explained

You may want to see also

Fungal spore survival strategies

Root fungi, such as *Armillaria* and *Rhizoctonia*, employ dual strategies for survival and propagation: spore dispersal and mycelial growth through roots. Spores, the microscopic reproductive units, are critical for long-distance colonization, while root-based mycelial networks ensure localized persistence. Understanding fungal spore survival strategies reveals how these organisms thrive in diverse environments, from forest floors to agricultural fields.

Spore dormancy is a key survival mechanism. Fungal spores can enter a dormant state, delaying germination until conditions are favorable. For instance, *Fusarium* spores can remain viable in soil for over a decade, waiting for optimal temperature and moisture levels. This resilience allows fungi to endure harsh conditions, such as drought or extreme temperatures, ensuring their longevity in unpredictable ecosystems. Farmers combating soil-borne pathogens often face this challenge, as dormant spores can re-emerge years after initial infection, necessitating long-term soil management strategies like crop rotation and fungicide application.

Another critical strategy is spore dispersal mechanisms. Fungi have evolved ingenious ways to spread spores over vast distances. For example, *Puccinia* (rust fungi) produce spores with hydrophobic surfaces, enabling them to be carried by wind or water with minimal resistance. Some fungi, like *Coprinus comatus*, use active mechanisms, such as forcibly ejecting spores into the air. Gardeners can mitigate spore spread by maintaining proper plant spacing and using barriers like row covers, reducing the risk of airborne transmission.

Spore adaptability further enhances survival. Fungal spores can alter their morphology or metabolism in response to environmental cues. *Aspergillus* spores, for instance, can switch between thick-walled and thin-walled forms depending on humidity levels, optimizing survival in dry or wet conditions. This plasticity allows fungi to colonize diverse habitats, from arid deserts to humid rainforests. For homeowners dealing with mold, understanding this adaptability underscores the importance of controlling indoor humidity below 60% and promptly fixing leaks to discourage spore germination.

Finally, spore-root synergy amplifies fungal survival. While spores enable dispersal, root-based mycelial networks provide stability and resource access. *Armillaria* fungi, for example, form extensive rhizomorphs (root-like structures) that connect infected plants, sharing nutrients and genetic material. This dual approach ensures that even if spores fail to germinate, the fungus can persist and spread through root systems. Landscapers managing infected trees should remove both aboveground debris and underground rhizomorphs to prevent recurrence, emphasizing the need to address both spore and root-based survival strategies.

In summary, fungal spore survival strategies—dormancy, dispersal, adaptability, and synergy with root systems—showcase the remarkable resilience of these organisms. By understanding these mechanisms, individuals can implement targeted interventions, whether in agriculture, gardening, or home maintenance, to manage fungal spread effectively.

Do All Anaerobic Bacteria Form Spores? Unraveling the Myth

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, many root fungi can spread by releasing spores into the soil, air, or water, which then germinate and infect new plants.

Yes, some root fungi can spread directly from infected roots to healthy roots through physical contact or by growing into adjacent plants.

While spores are a common method, root fungi can also spread through roots, infected plant debris, or via tools and equipment that come into contact with the fungus.

Yes, spores can be carried over long distances by wind, water, or animals, allowing root fungi to spread beyond the immediate area of infection.