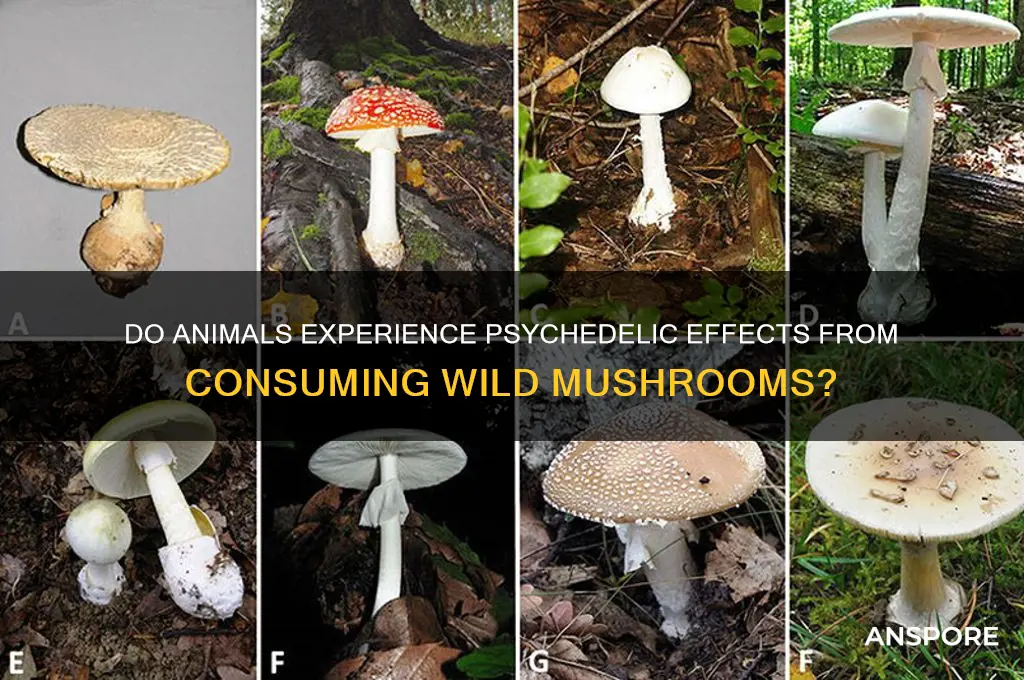

The question of whether animals can trip on mushrooms is both intriguing and complex, blending biology, chemistry, and behavior. While humans have long been aware of the psychoactive properties of certain mushrooms, such as those containing psilocybin, the effects on animals remain less understood. Anecdotal reports suggest that some animals, like dogs or cattle, may exhibit unusual behavior after ingesting wild mushrooms, but scientific research is limited. The key lies in whether animals possess the necessary receptors in their brains to process psychoactive compounds like psilocybin. Additionally, intentional exposure is rare, as animals typically avoid unfamiliar substances unless driven by hunger or curiosity. While the idea sparks curiosity, definitive answers require further study into animal neurobiology and their interactions with these fungi.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Can animals consume psychedelic mushrooms? | Yes, many animals have been observed eating psychedelic mushrooms in the wild. |

| Do animals experience psychoactive effects? | Evidence suggests some animals may experience altered states, but it’s unclear if they "trip" like humans. |

| Examples of animals consuming mushrooms | Reindeer, cattle, squirrels, and flies are known to eat psychedelic mushrooms. |

| Purpose of consumption | Often for nutritional value or accidental ingestion; intentional psychoactive use is not proven. |

| Behavioral changes observed | Reindeer eating Amanita muscaria may exhibit lethargy or agitation, but direct "tripping" behavior is not confirmed. |

| Scientific studies | Limited research; most evidence is anecdotal or observational. |

| Toxicity concerns | Some mushrooms are toxic to animals, but psychedelic varieties are generally not lethal in small doses. |

| Human vs. animal perception | Animals lack the cognitive framework to interpret psychedelic experiences as humans do. |

| Conclusion | Animals can consume psychedelic mushrooms, but whether they "trip" remains speculative and unproven. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Psilocybin effects on animal brains

Animals, like humans, possess serotonin receptors that psilocybin targets, raising the question: can they experience altered states of consciousness? Research on psilocybin's effects on animal brains is limited, but existing studies offer intriguing insights. For instance, a 2019 study published in *Nature* found that flies given psilocybin exhibited reduced fear responses and increased exploratory behavior, suggesting a potential anxiolytic effect. While flies are not mammals, their serotonin systems share evolutionary similarities, making them a valuable model for understanding psilocybin's mechanisms.

To explore psilocybin's effects on mammals, consider dosage and species-specific responses. Rats, commonly used in neuroscience research, show altered neuronal activity in the prefrontal cortex when administered psilocybin at doses ranging from 0.1 to 1.0 mg/kg. This region, critical for decision-making and perception, mirrors human brain changes during psychedelic experiences. However, translating these findings to larger animals or pets requires caution. Dogs, for example, metabolize psilocybin differently and may experience toxicity at lower doses, making intentional administration unethical and dangerous.

A comparative analysis reveals that while psilocybin affects animal brains, the subjective experience remains elusive. Unlike humans, animals cannot report hallucinations or emotional shifts. Instead, researchers rely on behavioral markers, such as altered locomotion or social interactions. For instance, octopuses, known for their intelligence, displayed increased exploratory behavior and playful interactions after psilocybin exposure in a 2021 study. This suggests that even invertebrates may experience some form of altered perception, though the nature of this experience remains speculative.

Practical considerations underscore the importance of ethical research. If studying psilocybin in animals, prioritize species relevance and welfare. Use controlled environments, monitor vital signs, and avoid doses exceeding 1 mg/kg for mammals. For pet owners, accidental ingestion of psilocybin mushrooms poses risks, including agitation, vomiting, and seizures. Immediate veterinary care is essential if exposure occurs. While the idea of animals "tripping" fascinates, their well-being must remain the priority.

In conclusion, psilocybin does affect animal brains, altering behavior and neuronal activity across species. However, the subjective experience remains a mystery, highlighting the gap between observable effects and internal states. As research progresses, ethical guidelines and species-specific considerations will be crucial in unraveling the complex interplay between psilocybin and animal consciousness.

Bipolar Disorder and Psilocybin: Exploring the Risks and Considerations

You may want to see also

Documented cases of animals ingesting mushrooms

Animals, both wild and domesticated, have been observed ingesting mushrooms in various environments, leading to a range of outcomes. Documented cases reveal that species such as reindeer, squirrels, and even cattle consume fungi as part of their diet or due to curiosity. For instance, reindeer in Scandinavia are known to eat *Amanita muscaria*, a psychoactive mushroom, during winter months when food is scarce. This ingestion alters their behavior, making them more docile and easier for predators to approach, though it also provides them with a temporary energy boost. Such observations highlight the complex relationship between animals and fungi, where consumption can serve both nutritional and accidental purposes.

In a more controlled setting, researchers have studied the effects of mushroom ingestion on primates. A notable case involved a group of Japanese macaques, which were observed eating *Psilocybe* mushrooms in the wild. The monkeys displayed altered behavior, including increased playfulness and reduced aggression, lasting several hours. While the exact dosage is difficult to measure, the behavioral changes suggest that the mushrooms had a psychoactive effect. This raises questions about the evolutionary significance of such interactions and whether animals actively seek out these experiences or simply tolerate them as a side effect of foraging.

Domesticated animals, particularly dogs, have also been involved in documented cases of mushroom ingestion, often with more harmful outcomes. Dogs are naturally curious and may consume mushrooms found in yards or during walks, leading to poisoning in many cases. For example, ingestion of *Amanita phalloides*, or the death cap mushroom, has resulted in severe liver failure and fatalities in dogs. Unlike wild animals that may have evolved tolerances or avoidance behaviors, pets rely on human intervention to prevent accidental poisoning. Pet owners are advised to familiarize themselves with local mushroom species and keep animals away from areas where toxic fungi grow.

Comparatively, herbivores like deer and cattle often ingest mushrooms as part of their grazing behavior, with varying consequences. Cattle in North America have been reported to eat *Panaeolus* mushrooms, which contain psilocybin, leading to temporary disorientation and lethargy. While these effects are generally mild and short-lived, they underscore the need for farmers to monitor grazing areas for potentially harmful fungi. In contrast, some animals, like squirrels, consume mushrooms without apparent adverse effects, possibly due to their smaller size or different metabolic responses. These differences highlight the importance of species-specific reactions to mushroom ingestion.

Practical tips for observing or managing animals around mushrooms include monitoring their behavior after foraging, especially in areas known for fungal growth. For pet owners, creating a mushroom-free zone in yards and using leashes during walks can prevent accidental ingestion. Wildlife enthusiasts should document and report unusual animal behavior near mushroom patches to contribute to scientific understanding. While some animals may "trip" on mushrooms, the outcomes range from benign to dangerous, emphasizing the need for awareness and caution in both natural and domestic settings.

Pregnant Women and Mushrooms: Safe or Risky? Expert Insights

You may want to see also

Behavioral changes in animals post-ingestion

Animals, like humans, can exhibit pronounced behavioral changes after ingesting psychoactive mushrooms, though the effects vary widely by species and dosage. For instance, a study on spiders revealed that those exposed to psilocybin-containing fungi spun geometrically irregular webs, deviating sharply from their usual symmetrical patterns. This suggests altered perception or motor control, highlighting how even small doses (approximately 0.1–0.5 mg/kg body weight) can disrupt innate behaviors. Such observations underscore the sensitivity of certain species to psychoactive compounds, even at levels far below human recreational doses.

In mammals, the response is more complex and often species-specific. Domestic dogs, for example, may display signs of agitation, disorientation, or lethargy after ingesting wild mushrooms, with symptoms appearing within 30–60 minutes of consumption. These reactions are typically dose-dependent; a small dog might show distress after consuming as little as 10–20 grams of certain mushroom species. In contrast, larger animals like cattle or deer often exhibit milder effects, possibly due to their size or metabolic differences. Owners and caretakers should monitor pets closely and consult veterinarians immediately if ingestion is suspected, as some mushrooms can cause severe toxicity unrelated to psychoactive effects.

Birds and reptiles present a less studied but equally intriguing case. Anecdotal reports suggest that birds, particularly corvids (like crows), may display heightened curiosity or altered social interactions after exposure to psychoactive substances. However, these observations are largely speculative, as controlled studies are scarce. Reptiles, with their slower metabolisms, may show delayed or prolonged reactions, though their behavioral repertoire is less expressive, making changes harder to interpret. Researchers caution against intentional exposure, emphasizing the ethical and health risks involved.

Practical tips for wildlife enthusiasts and pet owners include familiarizing oneself with local mushroom species and their effects. Keep animals away from areas where psychoactive or toxic fungi grow, especially during seasons of high mushroom activity (typically late summer to fall). If behavioral changes are observed, document symptoms (e.g., duration, intensity, specific actions) to aid veterinary diagnosis. While the idea of animals "tripping" may seem intriguing, the potential for harm far outweighs any curiosity, making prevention and vigilance paramount.

Can Chickens Safely Eat Mushrooms? A Comprehensive Feeding Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Toxicity risks for different animal species

Animals, like humans, can encounter toxic mushrooms in their environments, but the risks vary widely depending on species, metabolism, and behavior. For instance, dogs are particularly vulnerable to Amanita species, such as the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*), which contains amatoxins. Ingesting even a small piece—as little as 0.1 grams per kilogram of body weight—can lead to severe liver and kidney damage within 6 to 24 hours. Symptoms include vomiting, diarrhea, and lethargy, progressing to organ failure if untreated. Pet owners should immediately seek veterinary care if mushroom ingestion is suspected, as activated charcoal and supportive therapy can be life-saving.

In contrast, livestock such as cattle and sheep face risks from mushrooms like *Clitocybe dealbata*, which contains muscarine. This toxin causes excessive salivation, tearing, and gastrointestinal distress. While rarely fatal, affected animals may require symptomatic treatment, including atropine to counteract muscarinic effects. Interestingly, pigs are more resistant to many mushroom toxins due to their robust digestive systems, though they can still suffer adverse effects from high doses. Farmers should monitor grazing areas for mushroom growth, especially during wet seasons, and remove any suspicious fungi to prevent accidental poisoning.

Wildlife, particularly small mammals and birds, exhibit varying sensitivities to mushroom toxins. Squirrels and deer, for example, often consume mushrooms without ill effects, possibly due to evolved tolerance or selective feeding behaviors. However, species like the red squirrel have been documented suffering from tremors and disorientation after ingesting psychoactive mushrooms, suggesting some animals may "trip" unintentionally. Birds, on the other hand, are generally less affected by mushroom toxins, though exceptions exist, such as the toxic effects of *Galerina* species on certain bird populations.

Reptiles and amphibians are less studied in this context, but anecdotal evidence suggests they can be highly sensitive to mushroom toxins. A single *Amanita* cap ingested by a turtle or frog could prove fatal due to their slower metabolisms and smaller body masses. Terrarium owners should avoid introducing mushrooms into enclosures and promptly remove any that appear. Similarly, aquatic animals like fish and amphibians may be exposed to mycotoxins in water contaminated by decaying mushrooms, underscoring the need for clean habitats.

Understanding these species-specific risks is crucial for prevention and treatment. While some animals may exhibit curiosity or accidental ingestion, proactive measures—such as habitat monitoring, education, and prompt veterinary intervention—can mitigate toxicity risks. Each species’ unique physiology dictates its response to mushroom toxins, making tailored approaches essential for safeguarding animal health.

Weed Killer vs. Mushrooms: Uncovering the Truth About Fungal Fate

You may want to see also

Scientific studies on animals and psychedelics

Animals, like humans, possess serotonin receptors that psychedelics target, raising the question: can they experience altered states? Scientific studies have explored this, often using controlled environments to observe behavioral and physiological changes. For instance, a 2019 study published in *PLOS ONE* administered psilocybin to fruit flies, noting increased locomotor activity and altered courtship behaviors at doses equivalent to 0.01 mg/kg body weight. While flies lack subjective experience, these changes suggest psychedelics can disrupt normal neural pathways in non-human species.

One of the most instructive studies involved rats, where researchers at the University of Southern California examined the effects of DMT (a compound found in some mushrooms) on their brain activity. Rats were given doses ranging from 1 to 10 mg/kg, and EEG readings showed increased theta wave activity, similar to patterns observed in humans during psychedelic states. This suggests that, at a neurological level, animals may process these substances in ways analogous to humans. However, translating these findings to subjective experience remains speculative, as animals cannot report their perceptions.

A comparative study on primates offers further insight. In the 1960s, researchers at Stanford University observed monkeys after administering LSD, noting erratic behavior, dilated pupils, and reduced aggression at doses of 0.5 to 2.0 mg/kg. These primates, evolutionarily closer to humans, exhibited behaviors that could be interpreted as "tripping," such as repetitive movements and heightened responsiveness to stimuli. Yet, without verbal communication, the subjective nature of their experience remains unknown.

Practical considerations for such studies include ethical guidelines, as animal research with psychedelics must balance scientific curiosity with welfare. Researchers often use low doses to minimize distress, focusing on observable behaviors rather than hypothetical internal states. For example, a 2020 study on zebrafish exposed to psilocybin at 0.001 mg/L water concentration observed increased shoaling behavior, suggesting altered social dynamics. Such studies highlight the potential for psychedelics to influence animal behavior, even if the "trip" remains a human-centric concept.

In conclusion, while animals demonstrably react to psychedelics, the question of whether they "trip" remains unanswered. Scientific studies provide valuable data on behavioral and neurological changes but cannot confirm subjective experiences. Researchers must continue to approach this topic with rigor, ethics, and an awareness of the limitations in interpreting animal responses to these powerful substances.

Where to Find Golden Mushroom Soup: A Tasty Treasure Hunt

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, animals can experience psychoactive effects from consuming certain mushrooms, similar to humans. These effects can include altered behavior, disorientation, and hallucinations.

Various animals, such as reindeer, pigs, and cats, have been observed consuming psychedelic mushrooms. Reindeer in Siberia, for example, are known to eat *Amanita muscaria* mushrooms, which can cause them to act unusually.

No, it is not safe. Psychedelic mushrooms can be toxic to animals, causing severe symptoms like vomiting, seizures, or even death, depending on the species and the type of mushroom ingested. Always keep such mushrooms out of reach of pets and wildlife.