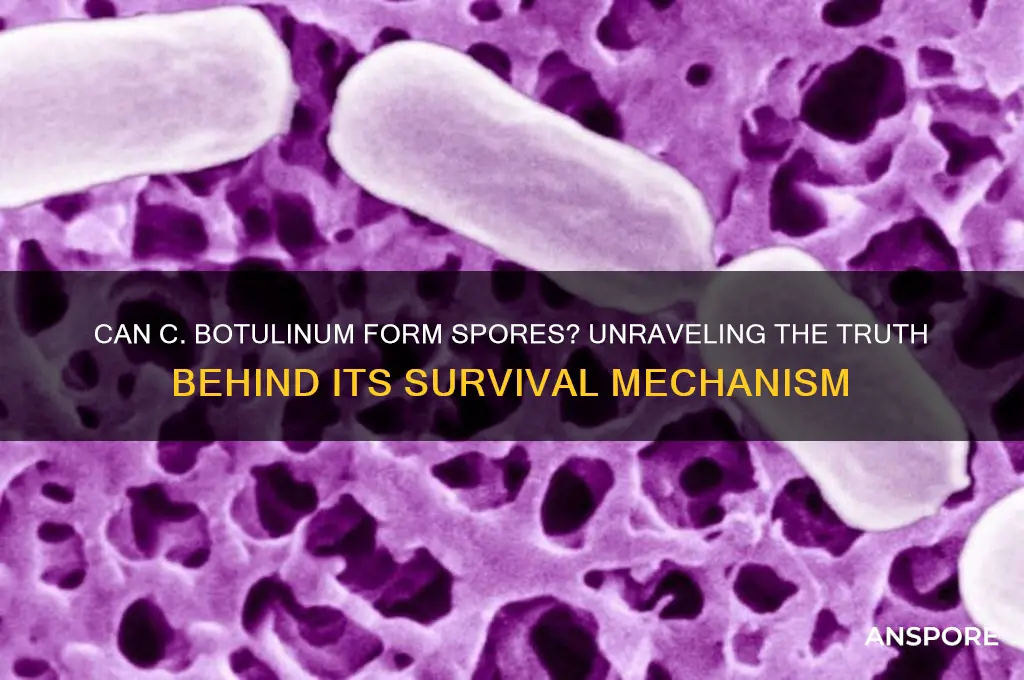

Clostridium botulinum, a bacterium notorious for producing the potent botulinum toxin, is a significant concern in food safety and human health. One of its most remarkable characteristics is its ability to form highly resistant endospores, commonly referred to as spores. These spores allow the bacterium to survive in harsh environmental conditions, such as high temperatures, low pH, and oxygen exposure, which would otherwise be lethal to the vegetative form of the organism. Understanding whether *C. botulinum* can form spores is crucial, as these spores are the primary means by which the bacterium persists in soil, water, and food products, posing a risk of contamination and toxin production under favorable conditions. This resilience underscores the importance of effective food preservation methods and public health measures to prevent botulism, a severe and potentially fatal illness caused by the ingestion of botulinum toxin.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Can C. botulinum form spores? | Yes |

| Type of spores | Endospores |

| Location of spore formation | Within the bacterial cell |

| Sporulation conditions | Anaerobic (without oxygen) and nutrient-limited environments |

| Spore resistance | Highly resistant to heat, radiation, desiccation, and disinfectants |

| Spore germination | Occurs when spores encounter favorable conditions (e.g., nutrients, warmth) |

| Role of spores in survival | Allows C. botulinum to persist in harsh environments and contaminate food |

| Public health significance | Spores can survive food processing, leading to potential botulism outbreaks if not properly inactivated |

| Inactivation methods | High-temperature processing (e.g., boiling, pressure cooking), irradiation, or specific disinfectants |

| Prevention strategies | Proper food handling, storage, and processing to prevent spore germination and toxin production |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Conditions for Sporulation: Nutrient depletion, oxygen limitation, and environmental stress trigger C. botulinum spore formation

- Spore Structure: Spores have a protective coat, cortex, and core, ensuring survival in harsh conditions

- Sporulation Process: Involves cell division, DNA replication, and formation of resistant endospores

- Survival Mechanisms: Spores withstand heat, desiccation, and chemicals, enabling long-term environmental persistence

- Clinical Significance: Spores can germinate in favorable conditions, leading to botulism toxin production

Conditions for Sporulation: Nutrient depletion, oxygen limitation, and environmental stress trigger C. botulinum spore formation

Clostridium botulinum, a notorious pathogen responsible for botulism, employs spore formation as a survival strategy under adverse conditions. This process, known as sporulation, is not a random event but a highly regulated response to specific environmental cues. Among these, nutrient depletion, oxygen limitation, and environmental stress emerge as the primary triggers, each playing a distinct role in signaling the bacterium to initiate spore formation.

The Role of Nutrient Depletion: Imagine a bustling bacterial colony feasting on a rich nutrient broth. As resources dwindle, C. botulinum senses the scarcity through intricate signaling pathways. This deprivation acts as a crucial signal, prompting the bacterium to shift its focus from growth and reproduction to long-term survival. Studies have shown that limiting essential nutrients like carbon and nitrogen sources significantly enhances spore formation in C. botulinum cultures. For instance, reducing the glucose concentration in the growth medium to below 0.1% can trigger a substantial increase in spore production.

Oxygen Limitation: A Double-Edged Sword: While oxygen is essential for many cellular processes, C. botulinum, being an obligate anaerobe, thrives in oxygen-depleted environments. Interestingly, oxygen limitation also serves as a potent trigger for sporulation. This might seem counterintuitive, as one would expect oxygen deprivation to hinder bacterial growth. However, C. botulinum has evolved to interpret oxygen limitation as a signal of impending environmental stress, prompting it to enter a dormant spore state. This adaptation ensures its survival in oxygen-poor environments, such as deep wounds or improperly canned foods.

Environmental Stress: A Multifaceted Trigger: Beyond nutrient depletion and oxygen limitation, various environmental stressors can induce C. botulinum sporulation. These include changes in pH, temperature fluctuations, and exposure to certain chemicals. For example, a sudden drop in pH to levels below 5.0 can significantly increase spore formation. Similarly, temperatures above 37°C (98.6°F) or exposure to sub-lethal concentrations of antibiotics can trigger the sporulation process. These diverse triggers highlight the bacterium's remarkable ability to sense and respond to a wide range of environmental challenges.

Understanding the specific conditions that induce C. botulinum sporulation is crucial for developing effective strategies to prevent foodborne botulism. By controlling nutrient availability, oxygen levels, and other environmental factors, food producers can minimize the risk of spore formation and subsequent toxin production. This knowledge also informs the development of targeted interventions, such as specific antimicrobial agents or processing techniques, to disrupt the sporulation process and ensure food safety. In the battle against this formidable pathogen, knowledge of its survival strategies is a powerful weapon.

Are Mold Spores Fat Soluble? Unraveling the Science Behind It

You may want to see also

Spore Structure: Spores have a protective coat, cortex, and core, ensuring survival in harsh conditions

Spores, the resilient survival forms of certain bacteria, owe their durability to a meticulously structured anatomy. At the heart of this structure lies the core, housing the bacterium’s genetic material and essential cellular machinery. Surrounding the core is the cortex, a thick, peptidoglycan-rich layer that provides structural integrity and protects against desiccation. Encapsulating both is the protective coat, often composed of proteins and lipids, which acts as a barrier against heat, chemicals, and radiation. This tri-layered design is not merely incidental but is evolution’s answer to ensuring survival in environments that would otherwise be lethal. For *Clostridium botulinum*, this spore structure is critical, as it enables the bacterium to persist in soil, water, and even canned foods, where it can remain dormant for years until conditions favor germination.

Consider the practical implications of this structure in food safety. *C. botulinum* spores can survive boiling temperatures (100°C) for several minutes, making them a significant concern in food preservation. The protective coat resists common sanitizers, while the cortex prevents water loss, allowing spores to endure extreme dryness. To neutralize them, food processors must employ specific techniques, such as pressure cooking at 121°C for 3 minutes, which penetrates the spore’s defenses. Home canners, beware: improper processing can leave spores intact, leading to botulism, a potentially fatal illness caused by the bacterium’s toxin. Understanding the spore’s structure underscores why standard cooking methods are insufficient and why precise protocols are non-negotiable.

A comparative analysis highlights the spore’s superiority over other bacterial survival mechanisms. Unlike vegetative cells, which rely on favorable conditions to thrive, spores are designed for endurance. For instance, while *E. coli* cells perish quickly under heat, *C. botulinum* spores remain unscathed. This resilience is further exemplified by their ability to withstand pH levels as low as 4.5, a trait exploited in certain food preservation methods like pickling. However, this very adaptability makes spores a double-edged sword: while beneficial in industrial applications like probiotic production, they pose a significant risk in foodborne illnesses. The spore’s structure, therefore, is both a marvel of biology and a cautionary tale in public health.

For those working in microbiology or food science, studying spore structure offers actionable insights. Researchers can target the protective coat with novel antimicrobial agents, disrupting its integrity and rendering spores vulnerable. Alternatively, understanding the cortex’s role in water retention could inspire new dehydration techniques for food preservation. Practical tips for laboratories include using sodium hypochlorite (5%) to disinfect surfaces contaminated with spores, as it effectively degrades the coat. For educators, illustrating spore structure with 3D models or animations can demystify their complexity for students. By dissecting the spore’s architecture, we not only appreciate its ingenuity but also unlock strategies to mitigate its risks and harness its potential.

Exploring Nature's Strategies: How Spores Travel and Disperse Effectively

You may want to see also

Sporulation Process: Involves cell division, DNA replication, and formation of resistant endospores

Clostridium botulinum, a bacterium notorious for producing the potent botulinum toxin, undergoes a remarkable transformation through sporulation. This process is not merely a survival mechanism but a complex sequence of events that ensures the bacterium’s persistence in harsh environments. At its core, sporulation involves three critical steps: cell division, DNA replication, and the formation of highly resistant endospores. These endospores are the bacterium’s armored vehicles, capable of withstanding extreme conditions such as heat, desiccation, and chemicals that would otherwise destroy the vegetative form. Understanding this process is crucial, as it explains how *C. botulinum* can survive in soil, sediments, and even canned foods, posing a persistent threat to food safety.

The sporulation process begins with an asymmetric cell division, where the bacterium divides into two unequal compartments: a larger mother cell and a smaller forespore. This division is not random but highly regulated, ensuring the forespore receives a complete copy of the bacterial DNA. DNA replication is a pivotal step, as it guarantees genetic continuity and the potential for future germination. Once the forespore is fully formed, the mother cell engulfs it, providing a protective environment for the maturation of the endospore. This engulfment is a unique feature of Gram-positive bacteria like *C. botulinum* and is essential for the endospore’s resilience. The mother cell then undergoes autolysis, sacrificing itself to release the mature endospore, which can remain dormant for years until conditions become favorable for growth.

From a practical standpoint, the sporulation process has significant implications for food preservation and safety. For instance, *C. botulinum* spores can survive boiling temperatures, making them a challenge to eliminate in canned foods. The recommended processing time for low-acid canned foods is 121°C for at least 3 minutes, a standard set to ensure spore destruction. However, even slight deviations in processing can allow spores to survive, highlighting the importance of precise control in food manufacturing. Home canners, in particular, must follow guidelines such as using pressure canners and verified recipes to mitigate the risk of botulism. Understanding sporulation underscores why proper canning techniques are not just recommendations but necessities.

Comparatively, the sporulation process of *C. botulinum* shares similarities with other spore-forming bacteria like *Bacillus anthracis* but differs in its ecological niche and toxin production. While *Bacillus* species often sporulate in response to nutrient depletion, *C. botulinum* sporulates in environments lacking oxygen, such as deep soil layers or improperly processed foods. This anaerobic requirement is a key factor in its association with foodborne illness. Unlike *Bacillus* spores, which are primarily a concern in medical and bioterrorism contexts, *C. botulinum* spores directly impact public health through contaminated food. This distinction emphasizes the need for targeted strategies to prevent sporulation and spore germination in food production.

In conclusion, the sporulation process of *C. botulinum* is a fascinating yet dangerous biological phenomenon. By mastering cell division, DNA replication, and endospore formation, this bacterium ensures its survival and proliferation in adverse conditions. For industries and individuals alike, this process demands vigilance in food handling and preservation. Practical measures, such as adhering to proper canning procedures and understanding the limitations of heat treatment, are essential to counteract the resilience of *C. botulinum* spores. By dissecting the sporulation process, we gain not only scientific insight but also actionable knowledge to protect public health.

Vascular Plants: Exploring Reproduction via Spores and Seeds

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$19.97 $21.99

Survival Mechanisms: Spores withstand heat, desiccation, and chemicals, enabling long-term environmental persistence

Clostridium botulinum, the bacterium responsible for botulism, is notorious for its ability to form highly resilient spores. These spores are not just a passive byproduct of the bacterium’s life cycle; they are a survival masterpiece, engineered to endure extreme conditions. Unlike the vegetative form of the bacterium, which is relatively fragile, spores can withstand heat, desiccation, and chemicals, ensuring the organism’s persistence in environments that would otherwise be lethal. This resilience is a key factor in the bacterium’s ability to contaminate food and cause disease, even in processed or preserved products.

Consider the heat resistance of *C. botulinum* spores: they can survive temperatures up to 100°C (212°F) for several minutes, far exceeding the boiling point of water. This is why proper food processing techniques, such as pressure canning at temperatures above 121°C (250°F) for at least 3 minutes, are critical to destroy spores in low-acid foods like vegetables, meats, and fish. Home canning methods that rely solely on boiling water (100°C) are insufficient to eliminate these spores, making them a significant risk factor for botulism outbreaks in improperly processed foods.

Desiccation, or extreme dryness, is another challenge *C. botulinum* spores effortlessly overcome. They can remain viable in dry environments for years, waiting for favorable conditions to germinate and produce toxin. This is particularly concerning in low-moisture foods like spices, herbs, and certain types of honey, where spores can persist undetected. For instance, infant botulism cases have been linked to the consumption of honey contaminated with *C. botulinum* spores, which can germinate in the intestines of babies under 12 months old, whose digestive systems are not yet fully developed to prevent spore activation.

Chemical resistance further underscores the survival prowess of *C. botulinum* spores. They are unaffected by many common disinfectants and preservatives, including concentrations of salt, sugar, and acids that would inhibit most other microorganisms. This resistance necessitates the use of specialized methods, such as high-pressure processing or irradiation, to ensure food safety. For example, in the food industry, products like canned meats and vegetables undergo rigorous testing to confirm the absence of viable spores, often requiring multiple hurdles of preservation techniques to mitigate risk.

Understanding these survival mechanisms is not just an academic exercise—it’s a practical necessity for preventing botulism. Home cooks and food processors must adhere to strict guidelines, such as using pressure canners for low-acid foods, avoiding feeding honey to infants, and maintaining proper hygiene during food preparation. By recognizing the tenacity of *C. botulinum* spores, we can implement targeted strategies to disrupt their persistence and protect public health. After all, the battle against botulism is won not by strength, but by knowledge and precision.

Can Botulism Spores Be Deadly? Uncovering the Lethal Truth

You may want to see also

Clinical Significance: Spores can germinate in favorable conditions, leading to botulism toxin production

Clostridium botulinum, a bacterium notorious for producing one of the most potent toxins known to science, has a survival strategy that amplifies its threat: spore formation. These spores, akin to bacterial time capsules, can endure extreme conditions—heat, desiccation, and chemicals—that would destroy the vegetative form of the bacterium. This resilience is not merely a biological curiosity; it is a critical factor in the clinical significance of botulism. When spores encounter favorable conditions—anaerobic environments, appropriate temperature, and nutrient availability—they germinate, reactivating the bacterium’s metabolic processes. This reawakening triggers toxin production, the root cause of botulism, a potentially fatal disease characterized by muscle paralysis.

Understanding the germination process is essential for prevention and treatment. Spores are commonly found in soil, sediments, and improperly processed foods, particularly low-acid canned goods. For instance, home-canned vegetables or meats that have not been heated to 121°C (250°F) for at least 30 minutes can harbor dormant spores. Once ingested, these spores can germinate in the intestines of infants or in wounds, where oxygen levels are low and conditions are ideal for growth. Infants under 12 months are particularly vulnerable due to their underdeveloped gut flora, which fails to compete with C. botulinum. This highlights the importance of avoiding honey and other potential spore sources in their diet, as even trace amounts can lead to germination and toxin production.

The clinical implications of spore germination extend beyond foodborne botulism. Wound botulism, often associated with traumatic injuries or injection drug use, occurs when spores introduced into a wound germinate in the anaerobic environment of damaged tissue. This form of botulism is less common but equally dangerous, as it can progress rapidly without early recognition. Treatment in such cases involves surgical debridement of the wound, antibiotic therapy, and, in severe cases, administration of botulinum antitoxin. The antitoxin neutralizes circulating toxins but does not affect toxins already bound to nerve endings, underscoring the urgency of early intervention.

Preventing spore germination is a cornerstone of botulism control. Commercial food processing employs stringent measures, such as high-pressure processing and thermal sterilization, to eliminate spores. At home, pressure canning at 15 psi for 20–100 minutes, depending on the food type, is recommended to destroy spores in low-acid foods. For infants, breastfeeding and delaying the introduction of solid foods until 6 months can reduce exposure risk. In healthcare settings, vigilance for wound botulism in at-risk populations, such as individuals with puncture wounds or those who use black tar heroin, is crucial. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment can significantly improve outcomes, transforming a potentially lethal condition into a manageable one.

The interplay between spore germination and toxin production underscores the dual nature of C. botulinum: a dormant threat waiting for the right conditions to unleash its deadly payload. This knowledge informs public health strategies, from food safety regulations to medical protocols, ensuring that the bacterium’s survival mechanism does not translate into human tragedy. By targeting spore germination, we can disrupt the chain of events leading to botulism, safeguarding individuals and communities from this silent menace.

Stun Spore vs. Electric Types: Does It Work in Pokémon Battles?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, C. botulinum is a spore-forming bacterium, meaning it can produce highly resistant endospores under unfavorable conditions.

C. botulinum forms spores in response to nutrient depletion, oxygen exposure, or other environmental stresses that limit its growth.

While the spores themselves are not toxic, they can germinate into active bacteria in favorable conditions (e.g., anaerobic environments) and produce botulinum toxin, which is highly dangerous.

C. botulinum spores can be inactivated through high-temperature treatments, such as boiling for several minutes or using pressure canning at 121°C (250°F) for at least 30 minutes.