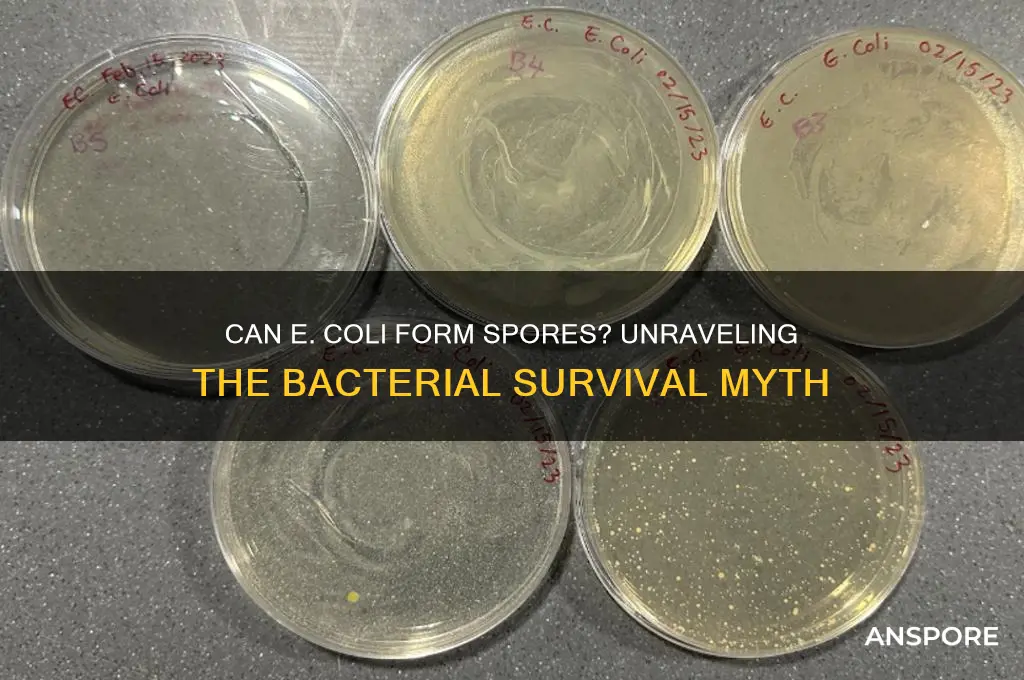

*Escherichia coli* (*E. coli*), a well-known bacterium commonly found in the intestines of humans and animals, is widely studied for its role in both beneficial and pathogenic processes. While some bacteria, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, are known for their ability to form spores as a survival mechanism in harsh conditions, *E. coli* does not possess this capability. Sporulation is a complex process involving the formation of a highly resistant endospores, which allows certain bacteria to withstand extreme environments like heat, desiccation, and chemicals. In contrast, *E. coli* relies on other strategies, such as biofilm formation and rapid reproduction, to survive adverse conditions. Understanding the differences in survival mechanisms between spore-forming bacteria and non-spore-forming bacteria like *E. coli* is crucial for fields like microbiology, food safety, and medicine.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Can E. coli form spores? | No |

| Reason | E. coli is a non-spore-forming bacterium. It lacks the genetic machinery and cellular structures necessary for sporulation. |

| Survival mechanisms | E. coli relies on other methods for survival in harsh conditions, such as forming biofilms, entering a dormant state (viable but non-culturable), or producing protective molecules like capsules and outer membrane proteins. |

| Related spore-forming bacteria | Some closely related bacteria, like Bacillus and Clostridium, can form spores, but E. coli does not share this ability. |

| Genetic basis | E. coli lacks the spo genes and other regulatory elements required for sporulation, which are present in spore-forming bacteria. |

| Practical implications | The inability of E. coli to form spores makes it more susceptible to environmental stresses, disinfection, and antimicrobial treatments compared to spore-forming bacteria. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- E. coli's Sporulation Ability: Does E. coli naturally produce spores under any conditions

- Stress-Induced Sporulation: Can environmental stress trigger spore formation in E. coli

- Genetic Modifications: Can engineered E. coli strains be made to form spores

- Comparison with Spore-Formers: How does E. coli differ from spore-forming bacteria like Bacillus

- Survival Mechanisms: What alternative strategies does E. coli use instead of sporulation

E. coli's Sporulation Ability: Does E. coli naturally produce spores under any conditions?

E. coli, a ubiquitous bacterium, is renowned for its adaptability across diverse environments, yet its sporulation ability remains a point of scientific scrutiny. Unlike spore-forming bacteria such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, which produce highly resistant endospores under stress, *E. coli* lacks the genetic machinery for sporulation. Its genome does not encode the complex network of genes required for spore formation, such as those involved in spore coat synthesis or cortex development. This absence is a fundamental distinction, as sporulation is an energy-intensive survival strategy that *E. coli* has not evolved to employ.

To understand why *E. coli* does not form spores, consider its ecological niche and survival strategies. *E. coli* thrives in nutrient-rich environments, particularly the mammalian gut, where it relies on rapid replication and metabolic versatility rather than long-term dormancy. Its survival mechanisms include biofilm formation, stress response proteins, and DNA repair systems, which suffice in its typical habitats. Sporulation, in contrast, is more common in bacteria that inhabit unpredictable or extreme environments, where long-term persistence is critical. *E. coli*'s lifestyle simply does not necessitate the extreme resilience spores provide.

Despite its inability to sporulate, *E. coli* can enter a viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state under stress, often mistaken for sporulation. In this state, cells become metabolically inactive and undetectable by standard culturing methods but retain viability. For instance, exposure to starvation, antibiotics, or temperature shifts can induce VBNC in *E. coli*. While this state enhances survival, it is distinct from sporulation, as VBNC cells lack the structural and protective features of spores. Researchers have explored inducing spore-like states in *E. coli* through genetic engineering, but such modifications are not natural processes.

Practical implications of *E. coli*'s non-sporulating nature are significant in food safety and clinical settings. Since *E. coli* does not form spores, standard heat treatments (e.g., pasteurization at 72°C for 15 seconds) are generally effective in eliminating it. However, its ability to enter the VBNC state poses challenges, as these cells may evade detection while remaining potentially pathogenic. Laboratories must employ molecular methods like PCR to identify VBNC *E. coli*, ensuring accurate risk assessments. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for developing targeted control measures and preventing outbreaks.

In conclusion, *E. coli* does not naturally produce spores under any conditions due to its genetic and ecological constraints. While it employs alternative survival strategies like the VBNC state, these mechanisms differ fundamentally from sporulation. This knowledge informs practical approaches to managing *E. coli* risks, emphasizing the importance of distinguishing between true spores and spore-like survival states in bacterial control strategies.

Are Spore Syringes Illegal? Understanding Legal Boundaries and Risks

You may want to see also

Stress-Induced Sporulation: Can environmental stress trigger spore formation in E. coli?

E. coli, a well-studied bacterium, is not known to form spores under normal conditions. However, the concept of stress-induced sporulation raises intriguing questions about its adaptive capabilities. While E. coli lacks the genetic machinery for sporulation, environmental stressors like nutrient deprivation, extreme temperatures, or oxidative stress can trigger survival mechanisms such as biofilm formation or persister cell development. These responses, though not sporulation, highlight the bacterium's resilience in harsh conditions.

To explore whether stress could induce spore-like states in E. coli, researchers have experimented with genetic engineering. For instance, introducing sporulation genes from Bacillus subtilis into E. coli has yielded limited success, with cells forming spore-like structures but lacking full viability. This suggests that while E. coli cannot naturally sporulate, external genetic manipulation might mimic sporulation under stress. Practical applications could include engineering E. coli for enhanced survival in industrial or environmental settings, but ethical and safety concerns must be addressed.

A comparative analysis of E. coli and spore-forming bacteria like Clostridium reveals stark differences in stress response strategies. Unlike Clostridium, which forms highly resistant spores, E. coli relies on rapid replication and metabolic flexibility. However, under prolonged stress, E. coli may enter a dormant state, reducing metabolic activity to conserve energy. This dormant state, while not a spore, shares similarities in stress adaptation. Understanding these mechanisms could inform strategies for controlling E. coli in food safety or medical contexts.

For those interested in experimenting with stress-induced responses in E. coli, a controlled laboratory setup is essential. Expose cultures to gradual stressors such as increasing salt concentrations (e.g., 5% NaCl) or temperature shifts (e.g., 45°C for 30 minutes). Monitor changes in cell morphology and viability using microscopy and plating techniques. While true sporulation will not occur, observing adaptive responses like cell aggregation or reduced growth can provide valuable insights into bacterial survival strategies. Always handle E. coli with proper biosafety measures, especially when inducing stress responses.

In conclusion, while E. coli does not naturally form spores, its stress-induced survival mechanisms offer a fascinating glimpse into bacterial adaptability. Genetic engineering and comparative studies provide pathways to explore spore-like states, though practical and ethical considerations remain. By understanding these responses, researchers can develop innovative solutions for industries ranging from biotechnology to environmental remediation, leveraging E. coli's resilience in novel ways.

Are Coliforms Spore-Forming? Unraveling the Truth About These Bacteria

You may want to see also

Genetic Modifications: Can engineered E. coli strains be made to form spores?

E. coli, a bacterium commonly found in the human gut, is not naturally known to form spores. Sporulation is a survival mechanism employed by certain bacteria, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, to withstand harsh environmental conditions. However, the inability of E. coli to form spores has sparked interest in whether genetic modifications could confer this capability. Advances in synthetic biology and genetic engineering have opened doors to manipulating bacterial traits, raising the question: Can engineered E. coli strains be made to form spores?

To explore this, researchers have attempted to transplant sporulation pathways from spore-forming bacteria into E. coli. One approach involves introducing genes from *Bacillus subtilis*, a well-studied sporulator, into E. coli. For instance, the *spo0A* gene, a master regulator of sporulation, has been a focal point. However, simply adding these genes is insufficient, as E. coli lacks the necessary cellular machinery and regulatory networks to complete sporulation. Partial success has been achieved, with E. coli forming spore-like structures, but these are often non-viable or incomplete. This highlights the complexity of engineering a trait as intricate as sporulation.

From a practical standpoint, engineering E. coli to form spores could revolutionize industries such as biotechnology and food preservation. Spore-forming E. coli could enhance its survival in extreme conditions, making it a robust chassis for producing biofuels, pharmaceuticals, or enzymes in challenging environments. For example, a spore-forming strain could withstand high temperatures or desiccation during industrial processes, reducing production costs. However, this raises ethical and safety concerns, as spore-forming E. coli could potentially become more difficult to control or eradicate in unintended settings.

A step-by-step approach to engineering sporulation in E. coli would involve: (1) identifying and synthesizing key sporulation genes from donor organisms, (2) integrating these genes into the E. coli genome or plasmids, (3) optimizing gene expression and regulation, and (4) screening for spore-like structures using microscopy and viability assays. Cautions include ensuring genetic stability, preventing horizontal gene transfer, and assessing the environmental impact of releasing such strains. Despite these challenges, ongoing research continues to push the boundaries of what is possible in bacterial engineering.

In conclusion, while E. coli does not naturally form spores, genetic modifications offer a tantalizing possibility of engineering this trait. Although current attempts have yielded incomplete results, the potential applications in biotechnology and industry make this a worthwhile pursuit. Balancing innovation with safety will be critical as scientists move closer to creating spore-forming E. coli strains. This endeavor not only tests the limits of synthetic biology but also underscores the intricate relationship between genetic design and cellular function.

Are Fern Spores Haploid? Unraveling the Mystery of Fern Reproduction

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Comparison with Spore-Formers: How does E. coli differ from spore-forming bacteria like Bacillus?

E. coli, a common inhabitant of the human gut, lacks the ability to form spores, a survival mechanism mastered by bacteria like *Bacillus*. This distinction is critical in understanding their ecological roles and responses to environmental stress. While *Bacillus* species, such as *B. anthracis* and *B. cereus*, can endure extreme conditions like heat, desiccation, and radiation by forming highly resistant endospores, E. coli relies on other strategies. For instance, E. coli can form biofilms or enter a dormant state under nutrient deprivation, but these mechanisms pale in comparison to the near-indestructible nature of spores. This fundamental difference influences their applications in industry and their behavior in clinical settings.

From a survival perspective, the spore-forming ability of *Bacillus* confers a significant evolutionary advantage. Spores can remain viable for decades, even centuries, in harsh environments, whereas E. coli’s survival outside a host is limited to days or weeks under favorable conditions. This disparity is evident in food safety, where spore-formers like *Clostridium botulinum* pose a greater risk due to their ability to survive pasteurization temperatures. In contrast, E. coli contamination is typically addressed through milder heat treatments or refrigeration, as it lacks the spore’s resilience. Understanding this difference is crucial for designing effective sterilization protocols in food and medical industries.

In laboratory and industrial settings, the inability of E. coli to form spores makes it a preferred organism for genetic engineering and bioproduction. Researchers favor E. coli for its rapid growth, well-characterized genetics, and ease of manipulation, traits that spore-formers often lack. However, this comes with a trade-off: E. coli’s vulnerability to environmental stress requires controlled conditions for cultivation. Spore-formers, on the other hand, are used in applications demanding robustness, such as probiotics (*B. subtilis*) or biocontrol agents, where their spore-forming ability ensures longevity and stability.

Clinically, the absence of spore formation in E. coli simplifies treatment strategies. Antibiotics and environmental stressors like heat or disinfectants are generally effective against E. coli, as it cannot revert to a spore state to evade eradication. In contrast, spore-forming pathogens like *Clostridioides difficile* require more aggressive treatments, often involving spore-targeting antibiotics or fecal transplants, due to the spores’ resistance to conventional therapies. This highlights the importance of distinguishing between these bacterial groups in infection control and treatment planning.

In summary, while E. coli and spore-forming bacteria like *Bacillus* share bacterial traits, their survival mechanisms diverge dramatically. E. coli’s reliance on biofilms and dormancy contrasts sharply with the spore’s unparalleled resilience. This comparison underscores the need for tailored approaches in research, industry, and medicine, emphasizing the unique challenges and opportunities each organism presents. Whether in a lab, factory, or hospital, recognizing these differences is key to harnessing their potential and mitigating their risks.

Spores vs. Seeds: Which is More Effective for Plant Propagation?

You may want to see also

Survival Mechanisms: What alternative strategies does E. coli use instead of sporulation?

E. coli, unlike spore-forming bacteria such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, lacks the ability to produce endospores. This absence of sporulation might seem like a survival disadvantage, but E. coli has evolved a suite of alternative strategies to endure harsh conditions. One such mechanism is the formation of biofilms, which are structured communities of bacteria encased in a self-produced protective matrix. Biofilms shield E. coli from antibiotics, host immune responses, and environmental stressors like desiccation and UV radiation. For instance, in healthcare settings, E. coli biofilms on medical devices can persist for weeks, posing significant infection risks. To mitigate this, clinicians often recommend antimicrobial coatings or frequent device changes, especially in catheterized patients.

Another survival tactic employed by E. coli is the adoption of a viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state. When exposed to stressors like nutrient deprivation or extreme temperatures, E coli can enter a dormant phase where it remains alive but cannot be cultured on standard laboratory media. This state allows the bacterium to evade detection while conserving energy. Research shows that E. coli in the VBNC state can survive in water systems for months, posing a potential public health threat. Water treatment facilities combat this by employing advanced filtration methods and disinfection protocols, such as chlorination or UV treatment, to ensure water safety.

E. coli also leverages genetic adaptability to survive adverse conditions. Through horizontal gene transfer, it can acquire resistance genes from other bacteria, enabling it to withstand antibiotics, heavy metals, and other toxins. For example, plasmids carrying genes for beta-lactamase production allow E. coli to degrade penicillin-based antibiotics. This adaptability is particularly concerning in clinical settings, where multidrug-resistant strains like ESBL-producing E. coli are increasingly prevalent. Healthcare providers combat this by adhering to strict antibiotic stewardship programs and isolating infected patients to prevent transmission.

Lastly, E. coli employs stress response systems, such as the RpoS regulon, to survive environmental challenges. The RpoS protein activates genes involved in osmotic stress tolerance, DNA repair, and nutrient scavenging. For instance, during starvation, RpoS induces the production of glycogen, a storage polysaccharide that provides energy reserves. This mechanism is particularly crucial in food processing environments, where E. coli can survive on surfaces for extended periods. To prevent contamination, food handlers are advised to maintain rigorous hygiene practices, including regular handwashing and surface disinfection with sanitizers containing at least 70% ethanol or quaternary ammonium compounds.

In summary, while E. coli cannot form spores, its survival arsenal includes biofilm formation, entry into the VBNC state, genetic adaptability, and stress response systems. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for developing targeted interventions in healthcare, water treatment, and food safety. By addressing these strategies, we can more effectively control E. coli’s persistence and mitigate its impact on public health.

Unveiling the Unique Appearance of Morel Spores: A Visual Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, E. coli (Escherichia coli) is not capable of forming spores. It is a non-spore-forming bacterium.

E. coli lacks the genetic and biochemical mechanisms required for sporulation, which are present in spore-forming bacteria like Bacillus and Clostridium.

No, there are no known strains of E. coli that can form spores. All E. coli variants are non-spore-forming.

E. coli survives harsh conditions through mechanisms like forming biofilms, entering a dormant state, or adapting to stress responses, but it does not produce spores.