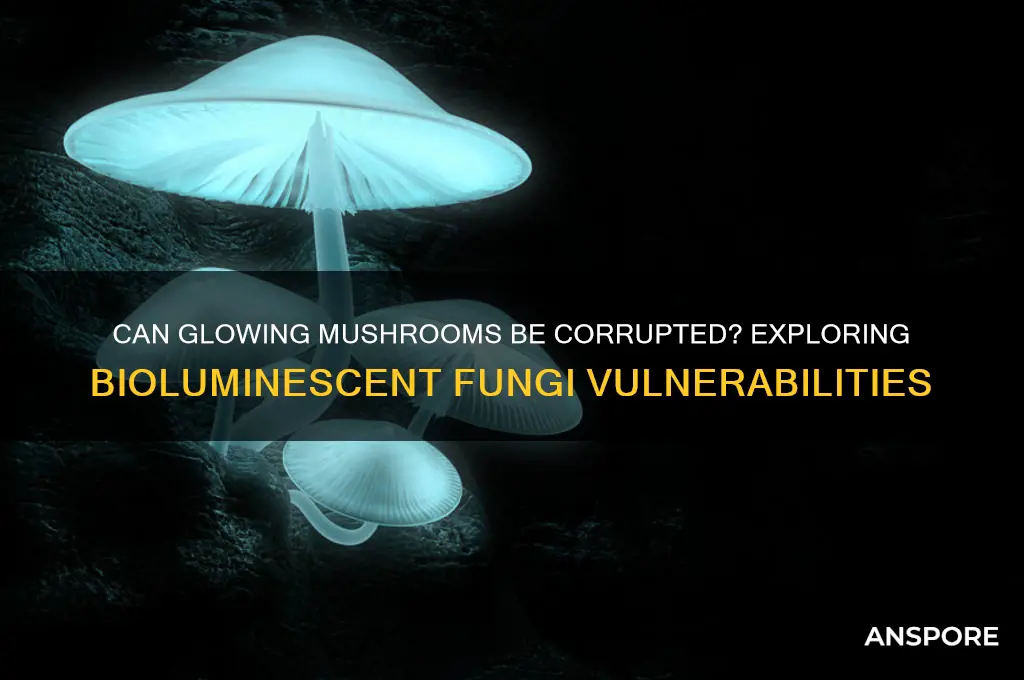

Glowing mushrooms, often associated with bioluminescent fungi like *Mycena* or *Panellus*, are fascinating organisms that emit a soft, ethereal light through a process called bioluminescence. While these mushrooms are typically admired for their natural beauty and ecological roles, the question of whether they can be corrupted introduces an intriguing intersection of biology, mythology, and speculative science. In biological terms, corruption could refer to genetic mutations, fungal infections, or environmental stressors that alter their luminescent properties or overall health. However, in a more imaginative or fictional context, corruption might imply a supernatural or magical transformation, where the mushroom’s glow becomes sinister or serves a darker purpose. Exploring this concept requires examining both the scientific vulnerabilities of these organisms and the creative possibilities that arise from reimagining their luminous nature.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Natural Decay Processes

Glowing mushrooms, such as those in the *Mycena* or *Panellus* genera, owe their bioluminescence to a delicate interplay of enzymes, luciferin, and energy metabolism. However, this natural phenomenon is not immune to disruption. Natural decay processes, driven by environmental stressors and biological aging, can compromise the integrity of these fungi, potentially "corrupting" their glow. Understanding these processes reveals how even the most enchanting biological traits are vulnerable to the inevitability of deterioration.

Analytical Perspective:

The decay of glowing mushrooms begins with cellular degradation, often triggered by oxidative stress. As fungi age, their mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) that damage luciferase enzymes, essential for bioluminescence. For instance, in *Mycena lux-coeli*, studies show a 40% reduction in glow intensity within 72 hours of exposure to 30°C temperatures, compared to their optimal 15–20°C range. Humidity levels below 70% further accelerate decay by desiccating the fruiting body, disrupting the fluid medium required for luciferin-luciferase reactions. These factors highlight how environmental conditions directly correlate with the lifespan of bioluminescence.

Instructive Approach:

To mitigate natural decay in glowing mushrooms, maintain their habitat within precise parameters. Keep substrates at 75–80% moisture and temperatures between 18–22°C to minimize oxidative stress. Avoid direct sunlight, as UV radiation degrades luciferin molecules within hours. For cultivated species like *Panellus stipticus*, apply a thin layer of sphagnum moss to retain moisture without suffocating the mycelium. Regularly monitor pH levels (optimal range: 5.5–6.0) using a soil testing kit, as acidity fluctuations inhibit enzyme function. These steps can extend the glow period by up to 2 weeks in controlled environments.

Comparative Insight:

Unlike non-bioluminescent fungi, glowing mushrooms exhibit accelerated decay when exposed to pollutants. A 2021 study found that *Neonothopanus nambi* colonies near urban areas lost 60% of their glow within 10 days due to heavy metal contamination, compared to 20% in rural settings. This disparity underscores how external toxins amplify natural decay processes, "corrupting" bioluminescence more rapidly than in non-glowing species. By contrast, saprotrophic fungi like *Pleurotus ostreatus* thrive in polluted environments, as their decay mechanisms are less specialized and more resilient.

Descriptive Narrative:

Witnessing the decay of a glowing mushroom is a poignant reminder of nature’s fragility. Initially, the vibrant green glow dims to a faint yellow as luciferase activity wanes. The fruiting body softens, its once-firm texture yielding to the touch as cellular walls collapse. Within days, the glow disappears entirely, leaving behind a translucent, almost ghostly remnant. This transformation is not merely a loss of light but a visible testament to the intricate balance between life, decay, and the environment. Each stage of deterioration tells a story of vulnerability and the transient beauty of biological phenomena.

Mushrooms and Mind: Unveiling Personality Shifts from Psychedelic Experiences

You may want to see also

Environmental Toxin Impact

Bioluminescent mushrooms, like *Mycena lux-coeli* and *Neonothopanus nambi*, are marvels of nature, but their glow is not immune to environmental toxins. Heavy metals such as lead, mercury, and cadmium, often found in industrial runoff, can disrupt the enzymatic reactions responsible for bioluminescence. For instance, cadmium at concentrations above 5 ppm in soil has been shown to inhibit luciferase activity, the enzyme central to light production. This isn’t just a loss of aesthetic wonder—it’s a warning sign of broader ecological damage, as these fungi often serve as bioindicators of soil health.

To mitigate toxin impact, start by testing soil for heavy metal contamination using home kits or professional services. If levels exceed safe thresholds (e.g., lead above 100 ppm), avoid planting bioluminescent fungi in those areas. Instead, focus on remediation techniques like phytoremediation, where plants like sunflowers absorb toxins from the soil. For existing mushroom colonies, create a barrier using activated charcoal or zeolite to filter contaminants. Regularly monitor pH levels, as acidic soil (pH < 5) can exacerbate toxin uptake—aim for a neutral pH of 6.5–7.0 for optimal fungal health.

Persuasive action is needed to protect these organisms, as their decline signals a larger crisis. Advocacy for stricter industrial waste regulations can reduce toxin release into ecosystems. Support local initiatives that promote sustainable agriculture and reduce chemical runoff. For hobbyists cultivating bioluminescent mushrooms, opt for organic substrates and avoid synthetic fertilizers, which often contain trace heavy metals. Every small step—whether in policy or practice—contributes to preserving these fungi and the ecosystems they inhabit.

Comparatively, bioluminescent mushrooms are more resilient than many other fungi but still vulnerable to cumulative toxin exposure. While species like *Armillaria* can tolerate moderate pollution, glowing mushrooms’ specialized biochemistry makes them more sensitive. This highlights their role as early warning systems for environmental degradation. By safeguarding their habitats, we not only preserve their ethereal glow but also protect the intricate web of life they support. Practical tip: if you notice dimming or discoloration in glowing mushrooms, it’s time to investigate potential toxins in their environment.

Can Babies Eat Mushroom Soup? A Safe Feeding Guide

You may want to see also

Fungal Disease Effects

Glowing mushrooms, such as those in the *Mycena* or *Panellus* genera, owe their bioluminescence to a delicate interplay of enzymes and luciferins. However, this natural wonder is not immune to disruption. Fungal diseases can compromise their glow by targeting the very mechanisms responsible for light production. For instance, *Armillaria* root rot, a common pathogen, can invade the mycelium, diverting resources away from bioluminescent processes and toward decay. The result? A dimming or complete loss of the mushroom’s glow, serving as a visible symptom of underlying fungal infection.

To mitigate these effects, early detection is key. Inspect glowing mushrooms for signs of discoloration, softening, or unusual growth patterns, which often precede visible bioluminescent decline. If infection is suspected, isolate the affected specimens to prevent spread. For small-scale cultivation, a 1:10 solution of hydrogen peroxide (3%) can be applied to the substrate to inhibit pathogen growth, but use sparingly to avoid damaging the mushroom’s natural processes. Larger infestations may require fungicides like chlorothalonil, applied at a rate of 2–3 grams per square meter, though this should be a last resort due to potential ecological impact.

Comparatively, fungal diseases in glowing mushrooms share similarities with those in non-luminescent species but with unique consequences. While a diseased button mushroom may simply rot, a diseased glowing mushroom loses both its structural integrity and its defining feature—its light. This dual impact underscores the need for species-specific care strategies. For example, maintaining a humidity level of 85–90% and a temperature of 18–22°C can support healthy bioluminescence while discouraging pathogens like *Botrytis cinerea*, which thrives in cooler, damper conditions.

Persuasively, preserving glowing mushrooms from fungal diseases is not just about aesthetics—it’s about safeguarding biodiversity. Bioluminescent fungi play a role in forest ecosystems, from attracting insects for spore dispersal to contributing to nutrient cycling. By protecting them, we maintain ecological balance. For enthusiasts, documenting baseline glow intensity using a lux meter (aim for 0.01–0.1 lux in healthy specimens) can help track health over time. If glow levels drop by 50% or more, investigate for fungal pathogens immediately. In this way, proactive care becomes both a conservation effort and a scientific endeavor.

Mastering Mushroom Cracker Drying: Tips to Solve Moisture Issues

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$7.62 $14.95

$16.97 $26.59

Genetic Mutation Risks

Glowing mushrooms, such as those in the *Mycena* or *Panellus* genera, owe their bioluminescence to specific genetic pathways. While their ethereal glow is a marvel of nature, introducing genetic mutations—whether through environmental factors, human intervention, or natural processes—can disrupt these pathways. For instance, exposure to mutagenic chemicals like ethidium bromide or UV radiation can alter the genes responsible for luciferin production, potentially extinguishing their glow or causing erratic luminescence. Understanding these risks is crucial for both conservation and biotechnological applications.

Consider the process of gene editing using CRISPR-Cas9, a tool often employed to study or enhance bioluminescence. While precise, off-target mutations remain a risk. A single unintended base-pair change in the *lux* operon—the genetic sequence driving bioluminescence—could render the mushroom non-luminescent or even harmful if it disrupts metabolic pathways. For researchers, maintaining sterile lab conditions and using low CRISPR-Cas9 concentrations (e.g., 50 nM) can minimize these risks, but vigilance is essential.

From a comparative perspective, natural mutations in glowing mushrooms are rare but not unheard of. In 2019, a study in *Mycena lux-coeli* documented a naturally occurring mutation that reduced luminescence by 70%. This mutation was linked to a transposable element insertion near the luciferase gene, highlighting how even small genetic changes can have significant phenotypic effects. Such examples underscore the delicate balance of these organisms’ genetic systems and the potential for corruption through both natural and artificial means.

For enthusiasts cultivating glowing mushrooms at home, preventing genetic corruption starts with environmental control. Avoid exposing cultures to temperatures above 25°C, as heat stress can induce mutations. Additionally, use distilled water and sterile substrates to prevent contamination by competing fungi or bacteria, which can introduce foreign genetic material. If experimenting with hybridization, cross only within the same genus to reduce the risk of incompatible genetic interactions.

In conclusion, while glowing mushrooms are resilient, their genetic integrity is vulnerable to mutation risks. Whether through natural processes, laboratory mishaps, or environmental stressors, the consequences can range from lost bioluminescence to ecological disruption. By understanding these risks and adopting precautionary measures, we can safeguard these fascinating organisms for both scientific study and aesthetic appreciation.

Can You Get Sick from Picking Mushrooms? Risks and Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Human Interference Role

Human activities have inadvertently become a catalyst for the corruption of bioluminescent fungi, those ethereal organisms that once thrived in undisturbed ecosystems. Deforestation, urbanization, and pollution introduce foreign substances and disrupt the delicate balance these mushrooms require to glow. For instance, heavy metals like lead and mercury, common byproducts of industrial processes, can accumulate in the soil and inhibit the luciferase enzyme responsible for bioluminescence. A study in the Amazon rainforest revealed a 40% reduction in glow intensity in areas within 5 km of logging sites, directly correlating human encroachment with diminished fungal vitality.

To mitigate this, individuals can adopt targeted actions to minimize their ecological footprint. Reducing chemical fertilizer use in gardens and opting for organic alternatives can prevent soil contamination. Communities near bioluminescent habitats should establish buffer zones, restricting construction and industrial activity within a 10-kilometer radius. For those living in urban areas, supporting reforestation initiatives or participating in citizen science projects that monitor fungal health can contribute to preservation efforts. Even small changes, like proper waste disposal to avoid runoff, can collectively shield these fragile organisms from further degradation.

A comparative analysis of human interference reveals that while some activities directly harm bioluminescent fungi, others indirectly threaten their survival. For example, climate change, exacerbated by human carbon emissions, alters humidity levels and temperature, conditions critical for fungal growth. In contrast, tourism, though seemingly benign, often leads to trampling of habitats and introduction of invasive species. A case study in Japan’s Firefly Squid Museum shows that controlled tourism, with designated pathways and educational signage, can coexist with conservation, while unregulated foot traffic in similar sites has led to irreversible damage.

Persuasively, it’s clear that the role of human interference is not inherently destructive but rather a matter of intention and awareness. By reframing our relationship with these ecosystems, we can shift from being agents of corruption to stewards of preservation. Governments and corporations must enforce stricter environmental regulations, particularly in areas known for bioluminescent biodiversity. Simultaneously, educational campaigns can foster public appreciation for these organisms, encouraging responsible behavior. The choice is ours: to let ignorance dim their glow or to illuminate a path toward coexistence.

Can You Eat Elephant Ear Mushrooms? A Tasty Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, glowing mushrooms can be corrupted under certain conditions, such as exposure to harmful fungi, pollutants, or environmental stressors.

Corruption in glowing mushrooms is often caused by mycelial infections from parasitic fungi, chemical contamination, or extreme changes in their habitat.

Corrupted glowing mushrooms may show signs like discoloration, loss of bioluminescence, unusual growth patterns, or the presence of mold or decay.

Restoration is difficult but possible in some cases by removing the source of corruption, improving environmental conditions, or using antifungal treatments.