Growing mushrooms from a cap is a fascinating topic that piques the curiosity of many gardening enthusiasts and fungi lovers. While it is possible to cultivate mushrooms from a cap under specific conditions, the process is not as straightforward as growing plants from seeds. Mushroom caps contain spores, which are the reproductive units of fungi, but successfully encouraging these spores to develop into a new mushroom requires a controlled environment, proper substrate, and specific humidity and temperature levels. This method, known as spore germination, is more complex than using pre-inoculated substrates or mushroom grow kits, making it a challenging yet rewarding endeavor for those willing to delve into the intricate world of mycology.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Feasibility | Possible, but not guaranteed |

| Success Rate | Low to moderate |

| Required Conditions | Sterile environment, proper substrate, humidity, and temperature |

| Time Frame | Several weeks to months |

| Common Mushrooms | Oyster, Shiitake, Lion's Mane (more likely to succeed) |

| Substrate Needed | Straw, sawdust, wood chips, or specialized mushroom growing kits |

| Humidity Requirement | 85-95% relative humidity |

| Temperature Range | 60-75°F (15-24°C), depending on species |

| Light Requirement | Indirect light, not direct sunlight |

| Contamination Risk | High, due to exposed tissue and lack of mycelium |

| Alternative Methods | Using spore prints or purchasing mycelium cultures for higher success rates |

| Common Issues | Mold growth, insufficient mycelium development, improper conditions |

| Tools Needed | Sterile containers, misting bottle, thermometer, hygrometer |

| Cost | Low to moderate, depending on materials and setup |

| Expertise Level | Intermediate; beginners may struggle with sterile techniques |

Explore related products

$14.99

What You'll Learn

- Spores vs. Mycelium: Understand the difference between spore-based and mycelium-based mushroom cultivation methods

- Cap Viability: Determine if a mushroom cap is fresh enough to grow new mushrooms from it

- Sterilization Steps: Learn how to sterilize tools and containers to prevent contamination during the process

- Substrate Selection: Choose the right growing medium, such as soil, wood chips, or straw, for success

- Humidity Control: Maintain optimal humidity levels to encourage mushroom growth from a cap fragment

Spores vs. Mycelium: Understand the difference between spore-based and mycelium-based mushroom cultivation methods

Growing mushrooms from a cap is a fascinating endeavor, but it’s not as straightforward as planting a seed. The cap itself doesn’t contain the necessary structures to regenerate a new mushroom. Instead, the key lies in understanding the reproductive mechanisms of fungi: spores and mycelium. While spores are the microscopic seeds of the fungal world, mycelium is the vegetative part—the root-like network that sustains the organism. Both are essential for cultivation, but they serve different roles and require distinct approaches.

Spore-based cultivation is the wild card of mushroom growing. Spores are released from the gills or pores of a mature mushroom cap and can disperse widely, but cultivating them is unpredictable. To use spores, you’ll need to create a spore print by placing a mature cap gill-side down on foil or paper for several hours. These spores are then transferred to a sterile agar medium, where they germinate into mycelium over 2–4 weeks. This method is advanced, requiring lab-like conditions to avoid contamination. It’s ideal for mycologists or hobbyists seeking to experiment with genetics, as spores allow for hybridization and new strains. However, it’s time-consuming and not beginner-friendly, with success rates varying widely based on sterility and technique.

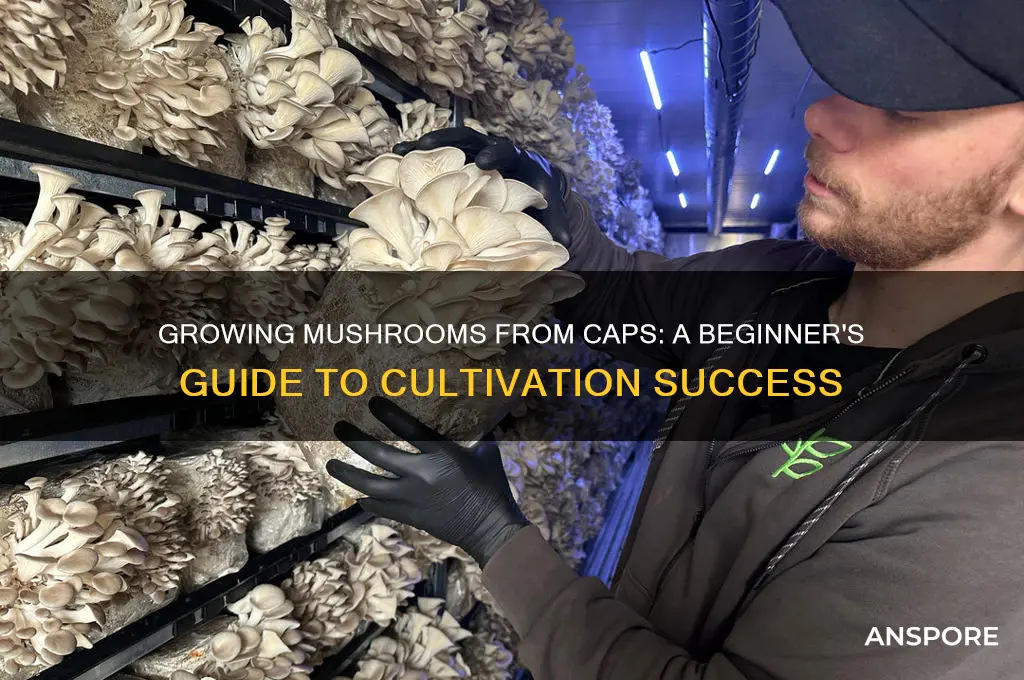

In contrast, mycelium-based cultivation is the practical, reliable method for most growers. Mycelium is already an established network, ready to fruit under the right conditions. You can obtain mycelium through tissue culture (taking a small piece of the mushroom’s stem or cap and growing it in a nutrient-rich medium) or by purchasing mycelium-inoculated grain spawn. This method bypasses the spore stage entirely, significantly reducing cultivation time. For instance, oyster mushrooms can fruit from mycelium-inoculated straw in as little as 2–3 weeks. Mycelium-based methods are forgiving, making them ideal for beginners or commercial growers who prioritize consistency and yield.

The choice between spores and mycelium depends on your goals. Spores offer genetic diversity and the thrill of experimentation but demand patience and precision. Mycelium provides efficiency and predictability, perfect for those focused on fruiting mushrooms quickly. For example, if you’re growing shiitake mushrooms, using mycelium-inoculated sawdust logs will yield results in 6–12 months, while starting from spores could extend the process by several months. Understanding these differences allows you to tailor your approach to your skill level and objectives.

Ultimately, while you can’t grow a mushroom directly from a cap, you can harness its spores or mycelium to cultivate new fungi. Spores are the starting point for genetic exploration, while mycelium is the fast track to fruiting bodies. Whether you’re a curious beginner or a seasoned grower, knowing the strengths and limitations of each method empowers you to choose the path that aligns with your ambitions.

Mushrooms' Lasting Effects: Unveiling Long-Term Impacts on Mind and Body

You may want to see also

Cap Viability: Determine if a mushroom cap is fresh enough to grow new mushrooms from it

Mushroom caps, when fresh and properly handled, can indeed serve as a starting point for growing new mushrooms. However, not all caps are created equal in terms of viability. The key to success lies in assessing the cap’s freshness, as older or damaged caps may lack the necessary spores or mycelium to initiate growth. A fresh cap should feel firm to the touch, with no signs of drying, discoloration, or mold. If the cap is soft, slimy, or has a strong, unpleasant odor, it’s likely past its prime and unsuitable for cultivation.

To determine cap viability, inspect its gills—the spore-bearing structures beneath the cap. Fresh gills should appear vibrant and intact, with no signs of spore release or decay. Gently press the cap’s surface; if it springs back, it retains enough moisture to potentially support mycelial growth. Conversely, a cap that feels brittle or leaves behind dry, flaky residue is unlikely to yield results. For optimal chances, select caps from recently harvested mushrooms, ideally within 24–48 hours of picking.

A practical method to test viability involves placing the cap gill-side down on a damp paper towel or sterile substrate. Keep it in a warm, humid environment (around 70–75°F) and monitor for signs of mycelium growth, such as white, thread-like structures spreading from the cap. This process can take 7–14 days, depending on the species. If no growth appears within two weeks, the cap is likely non-viable. Note that some mushroom species, like oyster mushrooms, are more amenable to this method than others, such as truffles or morels.

While experimenting with cap viability, exercise caution to avoid contamination. Sterilize tools and containers before use, and work in a clean environment. Even a small amount of bacteria or mold can outcompete the mushroom’s mycelium, rendering the attempt futile. For beginners, starting with store-bought mushrooms labeled as fresh and organic increases the likelihood of success, as these are less likely to have been treated with preservatives or pesticides that could hinder growth.

In conclusion, growing mushrooms from a cap hinges on its freshness and proper handling. By carefully assessing firmness, gill condition, and moisture content, you can gauge viability before investing time and resources. While not all attempts will succeed, this method offers a fascinating glimpse into the mushroom life cycle and can be a rewarding experiment for both novice and experienced cultivators alike.

Reishi Mushroom: Energy Booster or Sleep Aid? Unveiling the Truth

You may want to see also

Sterilization Steps: Learn how to sterilize tools and containers to prevent contamination during the process

Growing mushrooms from a cap is an intriguing endeavor, but success hinges on one critical factor: sterilization. Contamination from bacteria, mold, or other fungi can swiftly derail your efforts, turning your substrate into a petri dish of unwanted organisms. To prevent this, every tool and container that comes into contact with your mushroom culture must be meticulously sterilized. Here’s how to do it effectively.

Step 1: Gather Your Materials

Begin by assembling all tools and containers you’ll use, such as scalpel blades, jars, syringes, and growing substrates. Common sterilization methods include autoclaving, pressure cooking, or using chemical agents like isopropyl alcohol. For home growers, a pressure cooker is the most accessible option, capable of reaching the 121°C (250°F) needed to kill spores and bacteria. Alternatively, a 70% isopropyl alcohol solution can sterilize surfaces and small tools, though it’s less effective for porous materials.

Step 2: Clean Before Sterilizing

Sterilization is not effective if surfaces are dirty. Wash all items with hot, soapy water to remove visible debris, then rinse thoroughly. For glass jars, ensure no soap residue remains, as it can interfere with sterilization. After cleaning, allow items to air-dry completely or use a clean paper towel to avoid reintroducing contaminants.

Step 3: Apply the Sterilization Method

If using a pressure cooker, place your tools and containers inside, ensuring they don’t touch each other to allow steam penetration. Process at 15 psi for 30–60 minutes, depending on the load size. For alcohol sterilization, submerge small tools in 70% isopropyl alcohol for 10 minutes, then flame them briefly with a lighter to ensure no liquid remains. Always work in a clean environment, ideally with a still air box or laminar flow hood to minimize airborne contaminants.

Cautions and Practical Tips

Sterilization is unforgiving—even a single spore can ruin your project. Avoid overloading your pressure cooker, as this can prevent proper steam distribution. When using alcohol, ensure proper ventilation to avoid inhaling fumes. Label sterilized items clearly and store them in a clean, sealed container until use. Remember, sterilization is a one-time process; once exposed to air, items are no longer sterile.

Mastering sterilization is the backbone of successful mushroom cultivation from a cap. By meticulously cleaning, choosing the right method, and handling sterilized items with care, you create an environment where your mushroom culture can thrive uncontested. This step, though time-consuming, is non-negotiable—it’s the difference between a flourishing mycelium and a failed experiment.

Identifying Fresh, Safe, and Delicious Mushrooms: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Substrate Selection: Choose the right growing medium, such as soil, wood chips, or straw, for success

Growing mushrooms from a cap is an intriguing endeavor, but success hinges on one critical factor: substrate selection. The substrate, or growing medium, serves as the mushroom’s food source and environment, directly influencing yield, flavor, and overall health. While soil, wood chips, and straw are common choices, each has unique properties that align with specific mushroom species and growing conditions. Understanding these differences is essential for transforming a single cap into a thriving colony.

Analytical Perspective:

Straw, for instance, is ideal for oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) due to its high cellulose content, which these fungi readily decompose. Wood chips, rich in lignin, are better suited for shiitake (*Lentinula edodes*) or reishi (*Ganoderma lucidum*), which thrive on harder substrates. Soil, often enriched with compost, works well for button mushrooms (*Agaricus bisporus*) but can introduce contaminants if not sterilized properly. The choice depends on the mushroom’s mycelial preferences and the grower’s ability to manage moisture and aeration. For example, straw requires frequent misting to maintain humidity, while wood chips retain moisture longer, reducing maintenance.

Instructive Steps:

To select the right substrate, start by identifying the mushroom species you’re cultivating. For oyster mushrooms, pasteurize straw by soaking it in 160°F (71°C) water for 1–2 hours to kill competitors. For shiitake, supplement oak or beech wood chips with wheat bran (5–10% by volume) to boost nutrient content. If using soil, mix it with 30–40% composted manure and sterilize it at 160°F (71°C) for 6–8 hours to eliminate pathogens. Always ensure the substrate is pH-balanced (6.0–6.5 for most species) and properly hydrated (50–60% moisture content) before inoculating with the mushroom cap or spawn.

Comparative Insight:

Straw is cost-effective and readily available, making it a favorite for beginners, but it decomposes quickly, limiting its reuse. Wood chips are more durable and provide a longer-lasting substrate, though they require more initial preparation. Soil, while nutrient-rich, poses the highest risk of contamination and is less forgiving for novice growers. For small-scale projects, straw is often the best starting point, while wood chips are ideal for long-term or outdoor cultivation. Soil is best reserved for advanced growers with controlled environments.

Descriptive Takeaway:

Imagine a bed of golden straw, its fibers interwoven to create a breathable yet moisture-retentive home for oyster mushrooms. Contrast this with the dense, earthy aroma of wood chips, slowly releasing nutrients as shiitake mycelium colonizes its surface. Each substrate tells a story, shaping the mushroom’s growth and flavor profile. By matching the substrate to the species, you’re not just growing mushrooms—you’re crafting an ecosystem tailored to their needs. The right choice transforms a humble cap into a bountiful harvest, proving that in mushroom cultivation, the foundation is everything.

Shiitake vs. Portobello: Can These Mushrooms Be Swapped in Recipes?

You may want to see also

Humidity Control: Maintain optimal humidity levels to encourage mushroom growth from a cap fragment

Mushrooms thrive in environments that mimic their natural habitats, where humidity often hovers between 85% and 95%. When attempting to grow a mushroom from a cap fragment, maintaining this narrow humidity range is critical. Too little moisture, and the mycelium struggles to colonize the substrate; too much, and you risk contamination from molds or bacteria. A hygrometer becomes your indispensable tool here, allowing you to monitor levels precisely. Pair it with a humidifier or a simple DIY solution like a tray of water with pebbles to create a microclimate conducive to growth.

Consider the substrate as well—its moisture content must complement the ambient humidity. For instance, if using a grain spawn, aim for a moisture level of 50-60% before sterilization. Once the cap fragment is introduced, mist the substrate lightly but regularly, ensuring it remains damp but not waterlogged. A spray bottle with distilled water works well, as tap water may contain minerals that hinder growth. Remember, consistency is key; erratic humidity levels can stall or even reverse the colonization process.

Comparing this to other plant propagation methods highlights its uniqueness. Unlike seeds or cuttings, mushroom cap fragments rely entirely on mycelium expansion, a process highly sensitive to environmental conditions. While a seedling might tolerate a day of low humidity, mycelium is far less forgiving. This underscores the need for proactive humidity management—think of it as creating a spa-like environment for your fungi, where every detail is optimized for relaxation and growth.

Practical tips can make this process more accessible. For small-scale projects, a clear plastic container with air holes serves as an effective humidity chamber. Place a layer of damp perlite or vermiculite at the bottom to act as a reservoir, then position your substrate with the cap fragment on top. Cover the container to trap moisture, but check daily for signs of condensation or mold. If condensation builds up, briefly remove the lid to allow air exchange, then reseal. For larger setups, consider investing in a humidifier with a built-in hygrostat to automate the process.

Finally, patience is as vital as humidity control. Mycelium growth is a slow dance, often taking weeks before visible progress appears. Resist the urge to over-mist or constantly disturb the setup, as this can introduce contaminants or stress the mycelium. Instead, maintain steady conditions, document your observations, and trust the process. With optimal humidity and care, that humble cap fragment could become the nucleus of a thriving mushroom colony.

Can Ducks Safely Eat Wild Mushrooms? Risks and Guidelines

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

While it’s possible to grow mushrooms from a cap, it’s not as straightforward as using spores or mycelium. The cap contains spores, but success depends on proper conditions and techniques.

The most common method is to place the cap gill-side down on a sterile growing medium, like damp soil or agar, and maintain humidity and temperature to encourage spore germination.

It can take several weeks to months, as the spores need to germinate, colonize the substrate, and develop into mature mushrooms.

Not all mushroom caps will successfully grow into new mushrooms. Some species are easier to cultivate than others, and the cap must be fresh and free of contaminants.

Basic supplies like a sterile growing medium, a humid environment (e.g., a plastic container), and proper temperature control are necessary. Advanced setups may include a spore syringe or agar plates.