Planting mushrooms is a fascinating and rewarding endeavor that differs significantly from growing traditional plants. Unlike plants, mushrooms are fungi and do not require sunlight or soil to thrive; instead, they grow on organic matter such as wood chips, straw, or compost. Cultivating mushrooms involves creating a suitable environment, often using a substrate inoculated with mushroom spawn, and maintaining specific conditions like humidity and temperature. While it may seem challenging, with the right knowledge and materials, anyone can successfully grow mushrooms at home, whether for culinary purposes, ecological benefits, or simply the joy of nurturing a unique organism.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Can mushrooms be planted? | Yes, but not like traditional plants. Mushrooms are fungi and require specific conditions to grow. |

| Growing Medium | Mushrooms grow on organic material like wood chips, straw, coffee grounds, or specialized substrates (e.g., sawdust, grain). |

| Method | Typically grown from spawn (mycelium-inoculated material) rather than seeds. |

| Light Requirements | Low to indirect light; mushrooms do not require sunlight for photosynthesis. |

| Temperature | Most varieties thrive in temperatures between 55°F and 75°F (13°C–24°C). |

| Humidity | High humidity (85–95%) is essential for mushroom growth. |

| Watering | Substrate must remain moist but not waterlogged; misting or soaking may be required. |

| Time to Harvest | Varies by species, typically 2–6 weeks after spawning. |

| Common Varieties for Home Growing | Oyster, Shiitake, Lion's Mane, Button, Portobello. |

| Space Requirements | Can be grown in small spaces like containers, bags, or trays. |

| Difficulty Level | Moderate; requires attention to sterility and environmental conditions. |

| Benefits | Fresh mushrooms, sustainable practice, and potential for indoor gardening. |

| Challenges | Risk of contamination, specific environmental needs, and learning curve. |

Explore related products

$14.99

What You'll Learn

Choosing the Right Mushroom Species

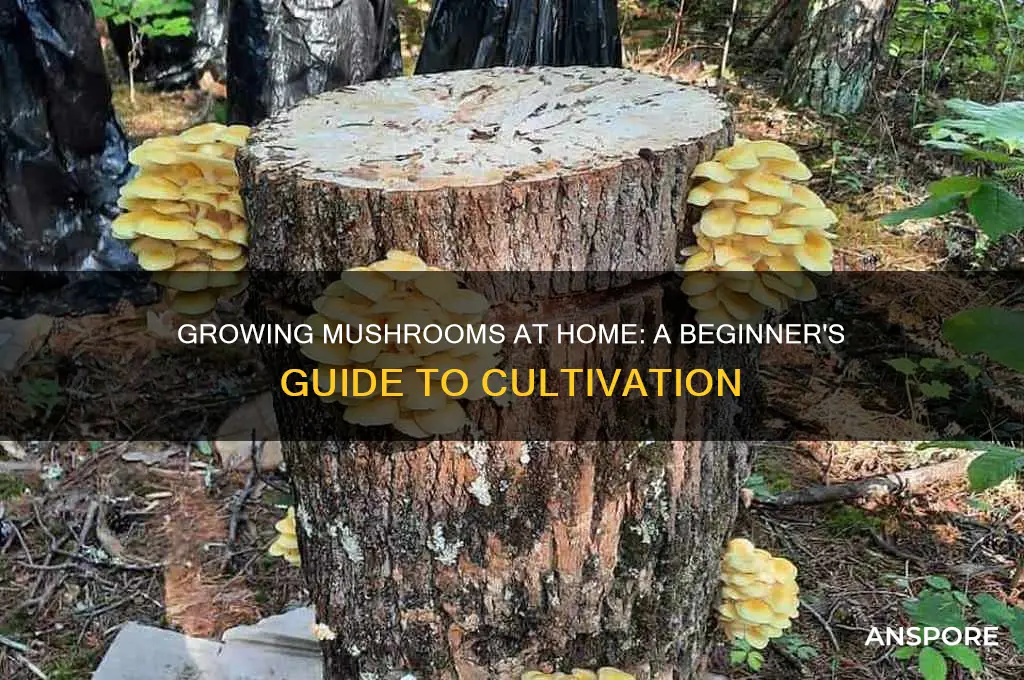

Not all mushrooms are created equal, and selecting the right species is crucial for a successful and rewarding cultivation experience. The first step is to consider your climate and growing conditions. Some mushrooms, like the popular Oyster mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*), are incredibly versatile and can thrive in a wide range of temperatures and environments, making them an excellent choice for beginners. In contrast, species such as the delicate Morel (*Morchella* spp.) require very specific conditions, often demanding advanced techniques and a deeper understanding of mycology.

A Matter of Taste and Purpose

The intended use of your mushrooms should significantly influence your choice. For culinary enthusiasts, the flavor profile and texture are key. Shiitake (*Lentinula edodes*) mushrooms, with their rich, umami taste and meaty texture, are a favorite in gourmet kitchens. On the other hand, the Lion's Mane (*Hericium erinaceus*) mushroom is gaining popularity for its unique, seafood-like flavor and potential cognitive health benefits, making it an intriguing choice for both chefs and health-conscious individuals.

Growth Characteristics and Space Considerations

Different mushroom species have distinct growth habits, and understanding these is essential for optimizing your yield. For instance, the Enoki (*Flammulina velutipes*) mushroom grows in tight clusters, making it ideal for small-space cultivation, such as in jars or small bags. Conversely, the Portobello (*Agaricus bisporus*) requires more room to develop its large, meaty caps, typically favoring outdoor beds or spacious indoor setups.

A Beginner's Journey: Starting Simple

For novice mushroom cultivators, starting with easy-to-grow varieties is a wise strategy. The Button mushroom (*Agaricus bisporus*), a common variety found in supermarkets, is a forgiving species that can be grown indoors with minimal equipment. Similarly, the White Elm Oyster (*Hypsizygus ulmarius*) is a robust species that fruits readily, providing a satisfying harvest for beginners. These species offer a gentle learning curve, allowing you to grasp the fundamentals of mushroom cultivation before advancing to more challenging varieties.

Advanced Techniques, Unique Rewards

As you gain experience, exploring more exotic species becomes an exciting prospect. The Pink Oyster (*Pleurotus djamor*), with its vibrant color and rapid growth, is a stunning addition to any mycologist's collection. However, it requires precise temperature control and a well-managed growing environment. Similarly, the Reishi (*Ganoderma lucidum*) mushroom, renowned for its medicinal properties, demands patience and specific techniques, often involving log cultivation and extended growing periods. These advanced species offer a unique challenge and the satisfaction of cultivating something truly special.

Toxic Mushrooms: Understanding the Risks and Symptoms of Poisoning

You may want to see also

Preparing the Growing Substrate

The foundation of successful mushroom cultivation lies in the growing substrate, a nutrient-rich medium that mimics the mushroom's natural habitat. This substrate is not merely a placeholder but a complex ecosystem, teeming with microorganisms and organic matter, which directly influences the mushroom's growth, yield, and quality. For instance, the substrate's pH, moisture content, and nutrient composition must be meticulously tailored to the specific mushroom species, as each has unique requirements. A slight deviation in these parameters can lead to poor colonization, contamination, or stunted growth, underscoring the critical importance of substrate preparation.

Analytical Perspective: Consider the case of oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*), which thrive in substrates with a high lignin content, such as straw or sawdust. The substrate's C:N ratio (carbon-to-nitrogen) is crucial; an ideal range of 30:1 to 50:1 ensures optimal mycelial growth. To achieve this, supplementing straw with nitrogen-rich materials like soybean meal (at a rate of 5-10% by weight) can significantly enhance colonization rates. This precision in substrate formulation highlights the interplay between organic chemistry and mycology, where small adjustments yield substantial improvements in cultivation outcomes.

Instructive Approach: Preparing a substrate for shiitake mushrooms (*Lentinula edodes*) involves a multi-step process. Begin by soaking hardwood sawdust (oak or beech preferred) in water for 24 hours to remove inhibitors. Next, pasteurize the sawdust by heating it to 60-70°C (140-158°F) for 1-2 hours, eliminating competing microbes. Allow the substrate to cool to 25-30°C (77-86°F) before mixing in wheat bran (20% by weight) and calcium carbonate (2% by weight) to balance pH and nutrients. Finally, sterilize the mixture in an autoclave at 121°C (250°F) for 1.5 hours to ensure a sterile environment for inoculation. This methodical approach ensures a clean, nutrient-dense substrate conducive to robust shiitake growth.

Comparative Insight: Unlike traditional soil-based gardening, mushroom cultivation relies on substrates that are often pasteurized or sterilized to eliminate competitors. For example, while button mushrooms (*Agaricus bisporus*) require a fully sterilized compost-based substrate, wine cap mushrooms (*Stropharia rugosoannulata*) can grow in non-sterile wood chip beds. This comparison illustrates the diversity in substrate requirements, even within the same kingdom. Home growers must therefore research their chosen species carefully, as the wrong substrate or preparation method can doom the project before it begins.

Descriptive Takeaway: Imagine a substrate as a finely tuned recipe, where each ingredient plays a specific role. For instance, a substrate for lion's mane mushrooms (*Hericium erinaceus*) might include beech sawdust (70%), bran (20%), and gypsum (2%), all mixed with precision. The sawdust provides structure and cellulose, the bran supplies nitrogen, and the gypsum stabilizes pH. When properly hydrated and sterilized, this mixture becomes a living matrix, ready to support the intricate network of mycelium. This attention to detail transforms a simple blend of materials into a thriving habitat, showcasing the artistry and science behind substrate preparation.

Mushrooms in Coal Mines: Unlikely Fungi Growth in Dark Depths

You may want to see also

Optimal Conditions for Growth

Mushrooms thrive in environments that mimic their natural habitats, which often include dark, cool, and humid conditions. Unlike plants, they don’t require sunlight for photosynthesis, but they do need a substrate rich in organic matter to feed on. For optimal growth, the substrate—whether straw, wood chips, or compost—must be properly pasteurized or sterilized to eliminate competing organisms. This step is critical because mushrooms are sensitive to contamination, which can quickly derail your cultivation efforts.

Temperature plays a pivotal role in mushroom development. Most edible varieties, such as oyster or shiitake mushrooms, prefer temperatures between 55°F and 70°F (13°C and 21°C). Deviations from this range can slow growth or even halt it entirely. For example, temperatures above 75°F (24°C) can stress mycelium, while colder conditions may delay fruiting. Monitoring temperature with a thermometer and using heating mats or insulation can help maintain the ideal range, especially in fluctuating climates.

Humidity is another non-negotiable factor, as mushrooms require moisture to develop properly. Relative humidity levels should be kept between 80% and 95% during the fruiting stage. This can be achieved by misting the growing area regularly or using a humidifier. However, excessive moisture can lead to mold or bacterial growth, so proper ventilation is essential. A balance must be struck: enough humidity to support mushroom growth, but not so much that it invites contaminants.

Light requirements for mushrooms are minimal but not nonexistent. While they don’t need sunlight, indirect light or low-intensity artificial light can signal the mycelium to begin fruiting. For instance, 8–12 hours of dim light per day can encourage pinhead formation in oyster mushrooms. Avoid direct sunlight, as it can dry out the substrate and harm the mycelium. Think of light as a gentle nudge rather than a necessity.

Finally, airflow is often overlooked but crucial for healthy mushroom growth. Stagnant air can lead to carbon dioxide buildup, which mushrooms are sensitive to, and can also create pockets of high humidity that foster contaminants. Introducing passive airflow through small vents or using a fan on low speed can prevent these issues. The goal is to create a microclimate that supports mushroom respiration without drying out the substrate.

By meticulously controlling these conditions—substrate preparation, temperature, humidity, light, and airflow—you can create an environment where mushrooms not only survive but flourish. Each factor interacts with the others, so consistency and attention to detail are key. With the right setup, even a beginner can transform a dark corner of their home into a thriving mushroom garden.

Can Toddlers Safely Eat Mushrooms? A Parent's Guide to Nutrition

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Harvesting and Storing Mushrooms

Mushrooms are ready for harvest when their caps are fully open but before the gills start to drop spores, a sign of overmaturity. For button mushrooms, this means picking them when the cap is about 2–3 inches in diameter. Oyster mushrooms are best harvested when the edges of the caps begin to flatten. Timing is critical: delayed harvesting reduces flavor and texture quality, while premature picking yields smaller, underdeveloped fruits. Use a sharp knife or your fingers to twist and pull the mushroom from the substrate, ensuring minimal damage to the mycelium, which can continue producing future flushes.

After harvesting, proper storage extends mushroom freshness. Refrigeration at 35–40°F (2–4°C) in a paper bag or loosely wrapped in a damp cloth is ideal. Plastic bags trap moisture, accelerating decay. For longer preservation, drying is effective: slice mushrooms thinly, spread them on a dehydrator tray at 125°F (52°C), and dry until brittle. Alternatively, freeze mushrooms by blanching them in boiling water for 2–3 minutes, plunging into ice water, then storing in airtight bags. Dried mushrooms last up to a year, while frozen ones retain quality for 6–12 months.

Comparing storage methods reveals trade-offs. Drying concentrates flavor, making dried mushrooms ideal for soups and stews, but rehydration is required. Freezing preserves texture better but can make mushrooms watery when thawed. Fresh storage is simplest but has the shortest shelf life, typically 5–7 days. Choose the method based on intended use: dried for long-term cooking, frozen for versatility, and fresh for immediate consumption.

A common mistake is washing mushrooms before storage, which introduces excess moisture and hastens spoilage. Instead, gently brush off dirt with a soft brush or wipe with a damp cloth just before use. For stored mushrooms showing signs of age—such as sliminess or off-odors—discard them immediately to avoid foodborne illness. Proper harvesting and storage not only preserve mushrooms but also maximize their nutritional value, including vitamins D and B, antioxidants, and fiber. Master these techniques, and your homegrown or foraged mushrooms will remain a culinary asset.

Are Canned Mushrooms Fattening? Uncovering the Truth About Their Caloric Impact

You may want to see also

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Mistake 1: Overwatering the Substrate

Mushroom cultivation thrives on moisture, but too much water can suffocate mycelium and breed mold. Beginners often equate "humid" with "soaked," leading to drowning substrates. The ideal moisture level is akin to a wrung-out sponge—damp but not dripping. Use a spray bottle to mist the growing environment daily, and ensure proper air circulation. For bulk substrates like straw or sawdust, aim for 60-70% moisture content; test by squeezing a handful—it should release one or two drops of water. Overwatering not only wastes effort but also invites contaminants that outcompete your mushrooms.

Mistake 2: Ignoring Sterilization Protocols

Contamination is the silent killer of mushroom grows, and improper sterilization is its gateway. Simply boiling substrates or using rubbing alcohol on tools isn’t enough for advanced grows. Autoclaving substrates at 121°C (250°F) for 1-2 hours is the gold standard, as it eliminates spores and bacteria. For small-scale projects, pressure cooking works, but avoid microwave sterilization—it’s inconsistent. Even a single overlooked spore can derail weeks of work. Invest in a reliable sterilization method, and treat your workspace like a lab: clean gloves, disinfected surfaces, and filtered air are non-negotiable.

Mistake 3: Misjudging Temperature and Light

Mushrooms aren’t sunbathers, but they’re sensitive to temperature fluctuations. Most species prefer a steady 65-75°F (18-24°C) during colonization and 55-65°F (13-18°C) during fruiting. Placing them near windows or heaters can cause stress, stunting growth or triggering abnormal fruiting. Light requirements are minimal—indirect, natural light or a few hours of fluorescent light daily suffices to signal fruiting. Avoid direct sunlight, which can dry out the substrate or overheat the mycelium. Think of mushrooms as cave dwellers: cool, dark, and consistent.

Mistake 4: Harvesting Too Early or Too Late

Timing is critical when harvesting mushrooms. Pick too early, and you’ll sacrifice yield; wait too long, and spores will drop, contaminating future flushes. For most varieties, harvest when the caps flatten and the veil beneath breaks. Oyster mushrooms, for instance, are best picked when the edges begin to curl upward. Use a clean knife or scissors to cut at the base, avoiding pulling, which can damage the mycelium. Proper timing ensures maximum biomass and preserves the substrate for subsequent flushes. Observe daily during the fruiting stage—mushrooms can mature rapidly, often within 24-48 hours.

Mistake 5: Neglecting Post-Harvest Care

After harvesting, many growers abandon the substrate, assuming it’s spent. However, most mushroom species produce multiple flushes if cared for properly. After picking, soak the substrate in cold water for 24 hours to rehydrate it, then drain and return it to fruiting conditions. For example, shiitake mushrooms can yield up to three flushes with proper care. Between flushes, maintain humidity and temperature, and remove any leftover mushroom bits to prevent mold. Treat your substrate like a rechargeable battery—with the right care, it’s far from single-use.

Growing Morel Mushrooms in Ohio: Tips, Conditions, and Success Strategies

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mushrooms are fungi, not plants, and require different conditions to grow. Instead of planting seeds, you typically grow mushrooms from spores or mycelium, often using a substrate like wood chips, straw, or compost.

While it’s possible to try, store-bought mushrooms are often treated to prevent contamination and may not produce spores or mycelium suitable for growing. It’s better to use mushroom spawn or kits specifically designed for cultivation.

Yes, mushrooms can be grown indoors with the right conditions. You’ll need a growing kit or spawn, a suitable substrate, proper humidity, and indirect light. Common varieties like oyster or lion’s mane are beginner-friendly for indoor cultivation.