Testing whether a mushroom is poisonous is a critical concern for foragers and nature enthusiasts, as misidentification can lead to severe illness or even death. While there are some folklore methods, such as observing animal consumption or using household items like silverware or garlic, these are unreliable and often debunked. The only accurate way to determine a mushroom’s toxicity is through proper identification by an expert or using detailed field guides and scientific resources. Even then, some poisonous mushrooms closely resemble edible varieties, making it essential to exercise extreme caution and avoid consuming wild mushrooms unless absolutely certain of their safety.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Visual Identification: Learn key physical traits like color, shape, and gills to spot toxic mushrooms

- Spore Print Test: Collect spores on paper to check color, aiding in species identification

- Chemical Tests: Use household items like iodine or bleach to detect color changes in poisonous varieties

- Animal Reactions: Observe pets or insects for signs of toxicity after mushroom exposure

- Expert Consultation: Submit samples to mycologists or use apps for accurate identification and safety

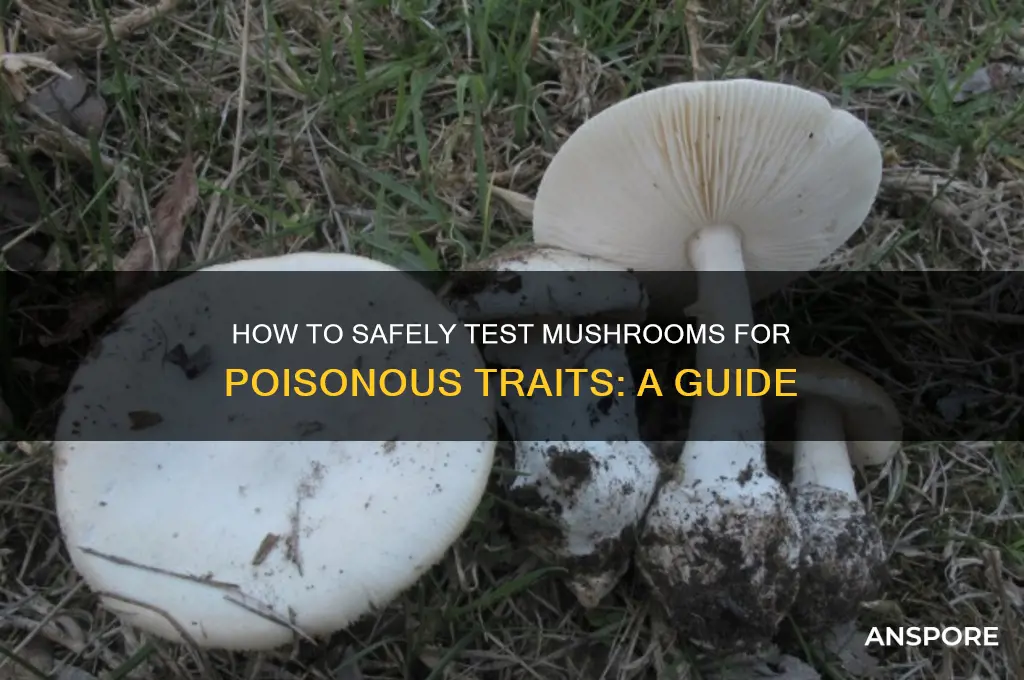

Visual Identification: Learn key physical traits like color, shape, and gills to spot toxic mushrooms

Mushroom hunters often rely on visual cues to distinguish between edible and toxic species, but this method is fraught with risk. While some poisonous mushrooms have distinctive features like bright colors or unusual shapes, many deadly varieties closely resemble their harmless counterparts. For instance, the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*) looks strikingly similar to edible paddy straw mushrooms, differing only in subtle details like the presence of a cup-like volva at the base. This underscores the importance of mastering specific physical traits beyond superficial appearances.

To begin, examine the mushroom’s cap and stem. Toxic species often display vivid colors—red, white, or yellow—though this is not a universal rule. The shape of the cap can also be telling: convex or umbrella-like caps are common in both edible and poisonous mushrooms, but a bell-shaped cap with a slimy texture, as seen in the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*), is a red flag. The stem’s structure is equally critical. A bulbous base or a ring (partial veil remnants) may indicate toxicity, as these features are prevalent in the *Amanita* genus, which contains some of the deadliest mushrooms.

Next, inspect the gills and spore print. Gills can be free, attached, or decurrent (extending down the stem), and their color can range from white to black. Toxic mushrooms often have white gills that do not change color with age, whereas edible varieties may darken as they mature. To create a spore print, place the cap gills-down on paper for several hours. A white spore print is common in poisonous species, while edible mushrooms often produce brown, purple, or black spores. This simple test can provide valuable confirmation, though it should not be the sole criterion.

Finally, consider the mushroom’s habitat and season. Toxic species like the Death Cap thrive in wooded areas, particularly under oak trees, while edible varieties like chanterelles prefer mossy environments. However, relying solely on habitat is risky, as mushrooms can grow in unexpected places due to environmental changes. Always cross-reference visual traits with multiple field guides or apps, and when in doubt, consult an expert. Visual identification is a skill honed over time, not a quick fix, and even experienced foragers avoid mushrooms they cannot definitively identify.

Can Guinea Pigs Safely Eat Oyster Mushrooms? A Complete Guide

You may want to see also

Spore Print Test: Collect spores on paper to check color, aiding in species identification

The spore print test is a simple yet powerful tool for mushroom identification, offering a glimpse into the hidden world of fungal reproduction. By capturing the spores released by a mushroom, you can unlock a unique identifier—their color. This method is particularly useful because spore color is a consistent characteristic, often remaining unchanged despite variations in other features like cap color or habitat. For instance, the spores of the deadly Amanita genus are typically white, while those of the edible Lactarius genus can range from cream to yellow.

Conducting the Test: To perform this test, you'll need a mature mushroom with open gills or pores, a piece of glass or wax paper, and a container. Place the mushroom cap, gills or pores facing downward, onto the center of your paper. Cover it with the container to create a humid environment, encouraging spore release. Leave this setup undisturbed for several hours or overnight. The spores will drop onto the paper, creating a colored deposit—your spore print.

This technique is especially valuable when distinguishing between similar-looking species. For example, the edible *Lactarius deliciosus* and the poisonous *Russula emetica* both have red caps, but their spore prints differ significantly—the former produces a cream-colored print, while the latter's spores are white. Such distinctions can be crucial in foraging, where misidentification can have serious consequences.

While the spore print test is a valuable skill for any mycologist or forager, it's essential to approach it with caution. Always ensure proper ventilation when handling mushrooms, as some species release spores that can cause allergic reactions or respiratory issues. Additionally, this test is just one piece of the identification puzzle; it should be used in conjunction with other characteristics like cap and stem features, habitat, and odor.

In the realm of mushroom identification, the spore print test stands as a unique and accessible method, providing a window into the microscopic world of fungi. It empowers enthusiasts and foragers to make more informed decisions, contributing to a safer and more enjoyable exploration of the fascinating kingdom of mushrooms. With practice, this technique becomes an invaluable skill, adding a new dimension to your mycological adventures.

Can Plants Thrive in Mushroom Compost Alone? A Gardening Guide

You may want to see also

Chemical Tests: Use household items like iodine or bleach to detect color changes in poisonous varieties

A drop of iodine on a mushroom cap can reveal more than you might expect. This simple household item, commonly found in kitchens for culinary purposes, can act as a rudimentary yet insightful tool for mushroom identification. When applied to certain species, iodine reacts by changing color, offering a visual clue about the mushroom's potential toxicity. For instance, the deadly Amanita genus often turns black or dark blue upon contact with iodine, a stark contrast to the brown or yellow hues it might display naturally. This reaction is due to the presence of specific toxins, such as amatoxins, which are absent in edible varieties. While not foolproof, this test can serve as an initial screening method, especially in the absence of expert guidance.

To perform this test, start by slicing a small piece from the mushroom's cap or stem. Ensure the cut surface is fresh and clean, as dirt or debris can interfere with the reaction. Apply a single drop of iodine tincture (typically a 2% solution) directly onto the exposed area. Observe the color change over the next few minutes, noting any shifts in hue or intensity. For comparison, test a known edible mushroom alongside the unknown specimen to establish a baseline. Keep in mind that this method is not definitive; some poisonous mushrooms may not react, and some edible ones might show unexpected changes. However, when used in conjunction with other identification techniques, it can provide valuable insights.

Bleach, another common household chemical, offers a different but equally intriguing approach to testing mushrooms. When applied to certain species, bleach can cause a rapid color change, often within seconds. For example, the Jack-O’-Lantern mushroom (*Omphalotus olearius*), a toxic look-alike of the edible chanterelle, turns bright orange or green when exposed to bleach. This reaction is due to the presence of illudins, toxins that break down in the presence of chlorine. To perform this test, dip a cotton swab in household bleach (typically 5-6% sodium hypochlorite) and gently rub it on the mushroom's gill or cap. Observe the area closely for any immediate color changes. As with iodine, this test should not be relied upon exclusively, but it can serve as a quick indicator of potential danger.

While these chemical tests can be informative, they come with limitations and risks. Neither iodine nor bleach can identify all poisonous mushrooms, and false negatives are common. Additionally, handling toxic species, even for testing, can be hazardous if proper precautions are not taken. Always wear gloves and avoid inhaling spores or fumes. Furthermore, these tests should never replace expert consultation or field guides. They are best used as supplementary tools for curious foragers or educators demonstrating mushroom identification techniques. For those new to mushroom hunting, investing in a reliable field guide or joining a local mycological society can provide safer, more accurate methods of distinguishing edible from poisonous varieties.

In conclusion, chemical tests using household items like iodine or bleach can offer a fascinating glimpse into the world of mushroom identification. While they are not definitive, they can serve as educational tools or preliminary checks in the field. By understanding their limitations and applying them carefully, foragers can enhance their knowledge of mushroom species and their potential risks. However, the ultimate takeaway remains clear: when in doubt, leave it out. No test, chemical or otherwise, is a substitute for expertise and caution in the realm of wild mushroom consumption.

Is Cream of Mushroom Soup Low Carb? A Diet-Friendly Analysis

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Animal Reactions: Observe pets or insects for signs of toxicity after mushroom exposure

Pets and insects can serve as unintended bioindicators of mushroom toxicity, offering clues before human consumption. Dogs, cats, and even flies may exhibit symptoms such as vomiting, diarrhea, lethargy, or seizures within 30 minutes to 2 hours after ingestion, depending on the mushroom species and dosage. For instance, Amanita phalloides, a highly toxic fungus, causes acute liver failure in dogs within 6–24 hours, often signaled by initial gastrointestinal distress. Observing these reactions can provide a critical warning, but it’s essential to act swiftly: contact a veterinarian immediately if exposure is suspected, as some toxins are fatal within 48 hours.

To use this method effectively, monitor pets closely after outdoor activities in mushroom-prone areas, especially during fall when fungi proliferate. Keep a detailed log of symptoms, including onset time and severity, as this data aids professionals in identifying the toxin. For insects, fruit flies exposed to toxic mushroom extracts in controlled studies show reduced lifespan and impaired motor function, though this requires laboratory conditions. While not a definitive test, animal reactions serve as a red flag, emphasizing the need for professional identification rather than reliance on this method alone.

A comparative analysis reveals limitations: animals metabolize toxins differently than humans, and false negatives are possible. For example, a dog might show no symptoms after eating a mildly toxic mushroom, while humans could still experience adverse effects. Conversely, some mushrooms harmless to humans, like Psilocybe species, cause distress in pets due to psychoactive compounds. This underscores the importance of cross-referencing observations with expert advice, such as consulting mycologists or poison control hotlines.

Practical tips include keeping pets leashed in wooded areas and removing visible mushrooms from their environment. For insects, while not a household test, research suggests that Drosophila melanogaster (fruit flies) exposed to sublethal doses of Amanita muscaria show altered behavior within 12 hours, a phenomenon studied in labs but not applicable for home testing. The takeaway is clear: animal reactions are a supplementary tool, not a substitute for expert identification. Always prioritize caution and professional guidance when dealing with unknown mushrooms.

Exploring Psilocybin: Can You Trip on Mushrooms Without Weed?

You may want to see also

Expert Consultation: Submit samples to mycologists or use apps for accurate identification and safety

Identifying whether a mushroom is poisonous requires expertise that most people lack. While folklore methods like observing color changes or animal avoidance are unreliable, consulting experts offers a scientifically grounded approach. Mycologists, specialists in fungi, can analyze samples using microscopic examination, chemical tests, and DNA sequencing to determine species and toxicity with high accuracy. For instance, submitting a fresh specimen in a paper bag (not plastic, to avoid mold) to a local university or mycological society can yield definitive results within days. This method is particularly crucial for species like the deadly Amanita phalloides, which closely resembles edible varieties.

For those seeking immediate answers, smartphone apps like iNaturalist or Mushroom ID leverage artificial intelligence and community verification to identify mushrooms from photos. While these tools are convenient, their accuracy depends on image quality and the app’s database. A 2022 study found that AI-based apps correctly identified 85% of common species but struggled with rare or degraded specimens. To maximize reliability, take clear photos of the mushroom’s cap, gills, stem, and base, and cross-reference results with multiple apps or expert feedback. However, apps should never replace professional consultation for consumption decisions.

The cost and accessibility of expert consultation vary. Mycological societies often provide free or low-cost identification services, while private labs may charge $50–$200 for detailed analysis. Apps, on the other hand, are typically free or require a one-time purchase of $5–$20. For foragers, investing in a consultation is far cheaper than the medical bills associated with mushroom poisoning, which can exceed $10,000 in severe cases. Additionally, joining a local mycological club can provide ongoing education and access to experts, reducing long-term reliance on paid services.

A comparative analysis highlights the strengths and limitations of both methods. Mycologists offer unparalleled precision but require time and physical samples, making them ideal for rare or ambiguous species. Apps provide instant feedback but are prone to errors with look-alike species or poor-quality images. For example, the Death Cap mushroom (Amanita phalloides) and the Paddy Straw mushroom (Volvariella volvacea) share similar features but vastly different toxicities—a mistake an app might make but an expert would not. Combining both approaches, such as using an app for preliminary identification followed by expert verification, offers the best balance of speed and safety.

In conclusion, expert consultation—whether through mycologists or technology—is the most reliable way to test if a mushroom is poisonous. While apps provide accessibility and convenience, they should complement, not replace, professional analysis. Foragers should prioritize submitting physical samples for critical cases and use apps as a supplementary tool. By leveraging both methods, individuals can enjoy the thrill of mushroom hunting without risking their health, ensuring that curiosity never outweighs caution.

Can You Safely Eat Brown Mushrooms? A Quick Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, this is not a reliable method. Some animals can tolerate poisonous mushrooms that are harmful to humans.

No, cooking or boiling does not neutralize most mushroom toxins. Poisonous mushrooms remain dangerous even after being prepared.

No, this is extremely dangerous. Many poisonous mushrooms have no distinct smell or taste, and tasting can lead to severe poisoning.

No, these methods are myths and have no scientific basis. The only reliable way to identify mushrooms is through expert knowledge or consultation with a mycologist.