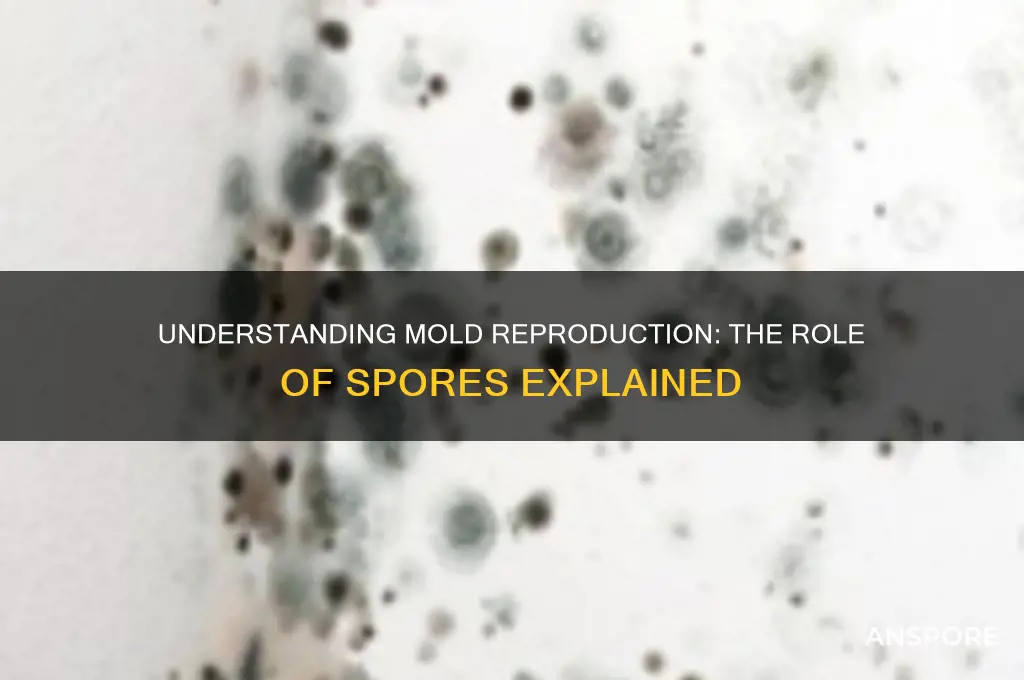

Mold, a type of fungus, reproduces primarily through the production of spores, which are microscopic, lightweight, and easily dispersed through air, water, or physical contact. These spores serve as the primary means of mold propagation, allowing it to spread rapidly under favorable conditions such as warmth, moisture, and organic material. When spores land on a suitable surface, they germinate and grow into new mold colonies, making them a highly efficient mechanism for mold reproduction and survival in diverse environments. Understanding how mold produces and disseminates spores is crucial for comprehending its lifecycle and implementing effective strategies to control and prevent mold growth.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproduction Method | Mold primarily reproduces through spores, which are microscopic, lightweight, and easily dispersed through air, water, or insects. |

| Types of Spores | Mold produces several types of spores, including asexual spores (e.g., conidia) and sexual spores (e.g., zygospores, ascospores, basidiospores). |

| Dispersal Mechanism | Spores are dispersed via air currents, water droplets, or by attaching to insects, animals, or human clothing. |

| Survival Conditions | Spores are highly resilient and can survive in harsh conditions, such as extreme temperatures, dryness, and lack of nutrients, until favorable conditions for growth arise. |

| Germination | Spores germinate when they land on a suitable substrate with adequate moisture, nutrients, and temperature, developing into new mold colonies. |

| Role in Mold Lifecycle | Spores are the primary means of mold propagation, allowing it to spread and colonize new environments efficiently. |

| Health Implications | Inhalation of mold spores can cause allergic reactions, respiratory issues, and other health problems in sensitive individuals. |

| Environmental Impact | Mold spores play a role in ecosystems by decomposing organic matter but can also cause damage to buildings, crops, and stored materials. |

| Detection Methods | Spores can be detected through air sampling, surface testing, and microscopic examination to assess mold presence and concentration. |

| Prevention and Control | Reducing moisture, improving ventilation, and regular cleaning are key strategies to prevent spore germination and mold growth. |

Explore related products

$13.48 $14.13

What You'll Learn

Mold Spores: Formation Process

Mold spores are the microscopic, seed-like units through which fungi reproduce, dispersing widely to colonize new environments. Their formation is a highly efficient process, essential for the survival and proliferation of mold species. The lifecycle begins with the maturation of fungal hyphae, the thread-like structures that make up the mold's body. Under favorable conditions—adequate moisture, nutrients, and temperature—these hyphae develop specialized structures called sporangia or spore-bearing organs. Within these structures, spores are produced through either asexual (mitotic) or sexual (meiotically) processes, depending on the species and environmental cues. This adaptability ensures mold can thrive in diverse habitats, from damp basements to decaying organic matter.

The formation of mold spores is a multi-step process, finely tuned by environmental signals. For asexual reproduction, hyphae first grow and branch extensively, forming a network called the mycelium. When conditions are optimal, the mycelium develops sporangia, which swell with immature spores. Inside the sporangia, cells undergo mitosis, dividing repeatedly to produce thousands of genetically identical spores. These spores, often single-celled and lightweight, are then released into the environment through mechanisms like wind, water, or physical disturbance. For example, the common mold *Aspergillus* produces spores in structures called conidia, which are easily dispersed by air currents, allowing rapid colonization of new surfaces.

Sexual spore formation, while less common, is equally fascinating. It occurs when compatible mold individuals (often of different mating types) fuse their hyphae, forming a zygote. This zygote undergoes meiosis, a process that shuffles genetic material, producing spores with unique genetic combinations. These spores, known as zygospores or ascospores, are typically more resilient, capable of surviving harsh conditions like drought or extreme temperatures. For instance, the mold *Penicillium* can produce ascospores that remain dormant for years before germinating when conditions improve. This genetic diversity and resilience are key to mold's success in challenging environments.

Understanding the spore formation process has practical implications for mold control. For instance, maintaining indoor humidity below 60% disrupts the moisture required for sporangia development. Regularly cleaning surfaces with mold-inhibiting agents, such as vinegar or hydrogen peroxide (3% solution), can prevent hyphae from maturing. In industrial settings, HEPA filters capture airborne spores, reducing their spread. For individuals with mold allergies, wearing N95 masks during cleanup minimizes spore inhalation. By targeting the spore formation process, these measures effectively curb mold growth, safeguarding both health and property.

In summary, mold spore formation is a sophisticated, environment-driven process that ensures fungal survival and propagation. Whether through asexual or sexual means, spores are produced in vast quantities, dispersed widely, and equipped to endure adverse conditions. This knowledge empowers us to implement targeted strategies for mold prevention and control, from humidity management to spore filtration. By disrupting the spore lifecycle, we can mitigate the risks associated with mold, from structural damage to respiratory issues, making environments safer and healthier.

Mildew Spores and Skin Irritation: Uncovering the Hidden Connection

You may want to see also

Sporulation Conditions in Mold

Mold, a ubiquitous fungus, relies on sporulation as its primary method of reproduction and dispersal. Sporulation conditions in mold are finely tuned to environmental factors, ensuring survival and propagation in diverse habitats. Temperature plays a pivotal role, with most molds favoring a range of 20°C to 30°C (68°F to 86°F) for optimal spore production. Deviations from this range can either inhibit sporulation or trigger it as a stress response, depending on the species. For instance, *Aspergillus niger* thrives at 30°C, while *Penicillium* species often sporulate efficiently at slightly cooler temperatures.

Humidity is another critical factor, as molds require moisture to initiate and sustain sporulation. Relative humidity levels above 70% are generally ideal, though some molds can sporulate at lower levels if other conditions are favorable. Water activity (aw), a measure of available moisture, typically needs to be above 0.8 for sporulation to occur. However, certain xerophilic molds, like *Wallemia sebi*, can sporulate at aw levels as low as 0.65, showcasing remarkable adaptability to dry environments.

Nutrient availability also influences sporulation. Molds often transition from vegetative growth to sporulation when nutrients become scarce, a process known as nutrient limitation. For example, nitrogen depletion can trigger sporulation in *Neurospora crassa*, a model organism in fungal biology. Additionally, the presence of specific carbon sources, such as cellulose or lignin, can either promote or inhibit sporulation depending on the mold’s metabolic capabilities.

Light exposure is an underappreciated but significant factor in sporulation. Many molds exhibit phototropism, with spores often produced on the surface of colonies exposed to light. Blue light, in particular, has been shown to stimulate sporulation in species like *Trichoderma*, while darkness may delay or reduce spore formation. This response is mediated by photoreceptors, highlighting the intricate interplay between environmental cues and fungal development.

Understanding sporulation conditions in mold has practical implications for both prevention and utilization. In indoor environments, controlling temperature, humidity, and light can mitigate mold growth and sporulation, reducing health risks associated with airborne spores. Conversely, in industrial settings, optimizing these conditions can enhance spore production for biotechnological applications, such as enzyme production or biocontrol agents. By manipulating sporulation conditions, we can either suppress unwanted mold proliferation or harness its reproductive potential for beneficial purposes.

Are Black Mold Spores Airborne? Understanding the Risks and Spread

You may want to see also

Types of Mold Spores

Mold spores are the primary means by which molds reproduce, dispersing through air, water, or insects to colonize new environments. These microscopic units are categorized into hyphal fragments, conidia, sporangiospores, and zygospores, each with distinct structures and dispersal mechanisms. Conidia, for instance, are asexual spores produced at the ends of specialized hyphae, while zygospores result from sexual reproduction, offering enhanced survival in harsh conditions. Understanding these types is crucial for identifying mold species and implementing targeted remediation strategies.

Conidia are among the most common mold spores encountered indoors, produced by fungi like *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium*. These spores are lightweight and easily become airborne, making them efficient colonizers of damp surfaces. Their resilience allows them to survive in dry conditions, posing health risks through inhalation, particularly for individuals with allergies or compromised immune systems. To mitigate conidia-related issues, maintain indoor humidity below 60% and promptly address water leaks or moisture accumulation.

In contrast, sporangiospores, produced by molds such as *Mucor* and *Rhizopus*, are released from sporangia, sac-like structures at the ends of hyphae. These spores are less common indoors but thrive in high-moisture environments like soil or decaying organic matter. While generally less allergenic than conidia, they can cause infections in immunocompromised individuals. Prevent their growth by ensuring proper ventilation in basements, bathrooms, and areas prone to dampness.

Zygospores, formed through the fusion of hyphae from compatible molds, are thicker-walled and more resistant to environmental stressors. This type is less frequently encountered indoors but is notable for its ability to remain dormant for extended periods, waiting for optimal conditions to germinate. While not typically allergenic, their presence indicates persistent moisture issues. Addressing water damage and using dehumidifiers can prevent the conditions that favor zygospore formation.

Finally, hyphal fragments are not spores per se but broken pieces of mold’s vegetative structure. These fragments can act as allergens and, under favorable conditions, regrow into new colonies. They are often found in dust and are particularly problematic in carpeted areas or HVAC systems. Regular cleaning with HEPA-filtered vacuums and air purifiers can reduce their presence, minimizing health risks associated with mold exposure.

In summary, recognizing the types of mold spores—conidia, sporangiospores, zygospores, and hyphal fragments—is essential for effective mold management. Each type has unique characteristics and requires specific prevention strategies. By targeting the conditions that favor their growth and dispersal, homeowners and professionals can reduce mold-related health risks and maintain healthier indoor environments.

Fern Spores: Mitosis or Meiosis? Unraveling the Reproduction Mystery

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Dispersal Mechanisms of Spores

Mold, a ubiquitous fungus, relies on spores for reproduction and survival. These microscopic structures are not just passive agents; they are engineered for efficient dispersal, ensuring the mold's persistence across diverse environments. Understanding the mechanisms behind spore dispersal is crucial for both scientific curiosity and practical applications, such as mold control in homes and industries.

One of the most common dispersal mechanisms is aerodynamic dispersal, where spores are carried by air currents. Molds like *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium* produce lightweight spores that can remain suspended in the air for extended periods, traveling miles before settling. This method is particularly effective in outdoor environments but also contributes to indoor mold issues when spores infiltrate through ventilation systems or open windows. To mitigate this, HEPA filters and regular air quality monitoring are recommended, especially in humid climates where mold thrives.

Another fascinating mechanism is water-mediated dispersal, often employed by molds in damp environments. Spores of species like *Stachybotrys* (black mold) are released into water droplets, which can then be transported through plumbing systems, condensation, or even flooding. This method is especially problematic in areas with water damage, where spores can colonize rapidly. Practical tips include fixing leaks promptly, using dehumidifiers to maintain indoor humidity below 60%, and inspecting areas prone to moisture accumulation, such as basements and bathrooms.

Biotic dispersal is a less obvious but equally important mechanism. Mold spores can attach to insects, animals, or even humans, hitching a ride to new locations. For instance, spores of *Cladosporium* are commonly found on the bodies of flies, which inadvertently transport them to food sources or other surfaces. To minimize this risk, maintain cleanliness in food preparation areas, seal waste bins, and use insect screens on windows and doors.

Finally, mechanical dispersal involves physical forces like wind, rain, or human activity dislodging spores from their source. This is particularly relevant in agricultural settings, where tilling soil or harvesting crops can release mold spores into the air. Farmers and gardeners can reduce this by using spore traps to monitor levels and timing activities to avoid peak spore release periods, typically early morning or after rain.

In conclusion, mold spores are dispersed through a variety of mechanisms, each adapted to specific environmental conditions. By understanding these processes, individuals can implement targeted strategies to control mold growth, whether in homes, workplaces, or agricultural settings. Awareness and proactive measures are key to minimizing the health risks and structural damage associated with mold proliferation.

Can Trees Catch Truffle Spores? Exploring Fungal Infections in Nature

You may want to see also

Environmental Factors Affecting Sporulation

Mold's ability to produce spores is a survival mechanism influenced by a delicate interplay of environmental factors. Understanding these factors is crucial for controlling mold growth in various settings, from homes to industrial environments. Here, we delve into the specific conditions that trigger or inhibit sporulation, offering actionable insights for prevention and management.

Temperature and Humidity: The Dynamic Duo

Sporulation in molds, such as *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium*, is highly sensitive to temperature and humidity. Optimal sporulation typically occurs within a temperature range of 22°C to 28°C (72°F to 82°F). Below 15°C (59°F) or above 35°C (95°F), sporulation rates decline significantly. Humidity plays an equally critical role; relative humidity levels above 70% create ideal conditions for spore production. For instance, in water-damaged buildings, mold colonies often sporulate rapidly due to elevated moisture levels. To mitigate this, maintain indoor humidity below 60% using dehumidifiers and ensure proper ventilation, especially in damp areas like basements and bathrooms.

Nutrient Availability: Fueling Sporulation

Molds require organic matter to produce spores, and nutrient availability directly impacts sporulation efficiency. Cellulose-rich materials, such as paper, wood, and drywall, are prime substrates for mold growth. In agricultural settings, crop residues left in fields can serve as nutrient sources, leading to widespread sporulation. To minimize risk, promptly remove organic debris from indoor and outdoor environments. In industrial processes, sterilizing equipment and surfaces can deprive molds of the nutrients needed for spore production.

Light Exposure: A Surprising Regulator

Light, particularly in the form of UV radiation, can both inhibit and stimulate sporulation depending on the mold species. For example, *Cladosporium* spp. often sporulate more profusely in the presence of light, while *Stachybotrys* (black mold) may be suppressed by UV exposure. In controlled environments, such as laboratories or food storage facilities, managing light exposure can be a strategic tool. Installing UV-C lamps in HVAC systems can reduce mold proliferation, but caution is advised, as prolonged UV exposure may damage materials or harm human health.

PH and Chemical Stressors: The Hidden Influencers

Molds thrive in neutral to slightly acidic environments, with optimal sporulation occurring at pH levels between 5.0 and 7.0. Extreme pH values, such as those found in highly acidic or alkaline solutions, can inhibit spore production. Chemical stressors, including fungicides and antimicrobial agents, also play a role. For instance, boric acid, commonly used in mold remediation, disrupts cellular processes and reduces sporulation. When applying chemical treatments, follow manufacturer guidelines to ensure effectiveness without causing material damage.

By manipulating these environmental factors, it is possible to control mold sporulation effectively. Whether in a residential, agricultural, or industrial context, proactive measures tailored to specific conditions can prevent mold proliferation and safeguard health and infrastructure.

Can Most Bacteria Form Spores? Unveiling Microbial Survival Strategies

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, mold reproduces primarily through spores, which are tiny, lightweight cells that can travel through the air and germinate under suitable conditions.

Mold spores spread through the air, on surfaces, or via water. They can enter homes through open doors, windows, vents, or attach to clothing, pets, and other objects.

Yes, when mold spores land on damp surfaces with sufficient nutrients, they can germinate and grow into new mold colonies, leading to further infestation.