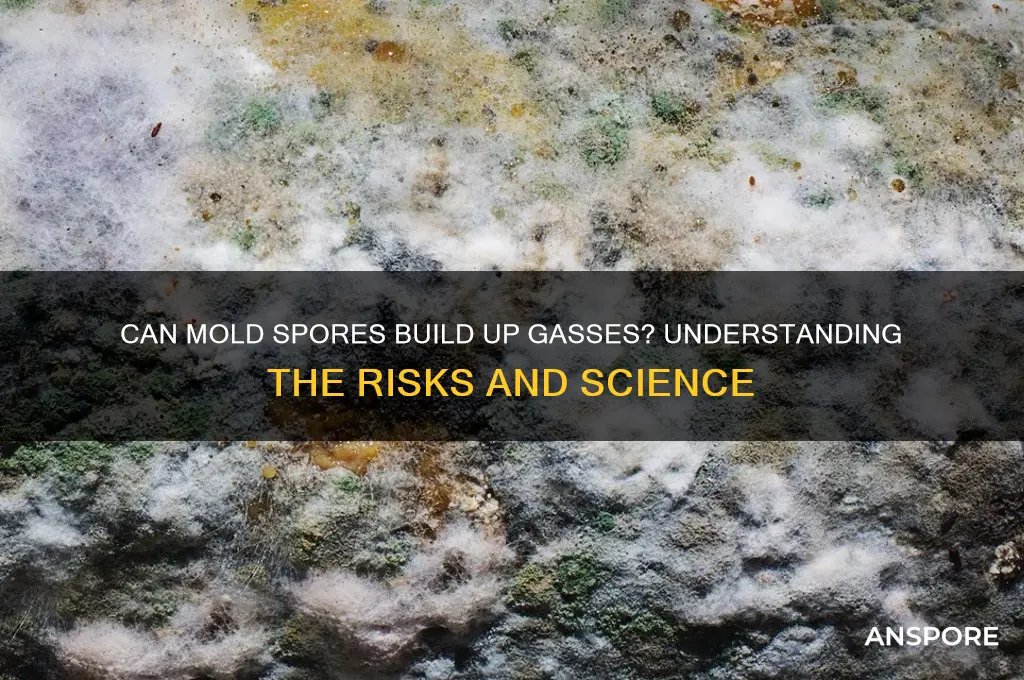

Mold spores, under certain conditions, can contribute to the buildup of gases, particularly in enclosed or poorly ventilated environments. As mold grows and metabolizes organic materials, it releases volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and other gases, such as carbon dioxide and methane, as byproducts of its decomposition processes. In confined spaces like basements, attics, or water-damaged buildings, these gases can accumulate, leading to potential health risks and unpleasant odors. Additionally, the presence of mold can exacerbate the production of gases like hydrogen sulfide or ammonia, especially when combined with bacterial activity. Understanding this relationship is crucial for addressing indoor air quality concerns and mitigating the health hazards associated with mold infestations.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Can Mold Spores Build Up Gases? | Yes, under certain conditions |

| Mechanism | Mold spores themselves do not produce gases, but active mold growth (mycelium) can release volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and gases like carbon dioxide (CO₂), methane (CH₄), and ethanol as byproducts of metabolism |

| Conditions for Gas Production | High moisture levels, organic matter availability, and suitable temperature (typically 20-30°C or 68-86°F) |

| Common Gases Produced | CO₂, CH₄, ethanol, and other VOCs (e.g., formaldehyde, benzene) |

| Health Risks | Exposure to mold-produced gases can cause respiratory issues, headaches, dizziness, and allergic reactions |

| Detection Methods | Air quality testing, VOC sensors, and mold inspection by professionals |

| Prevention | Control humidity (<60%), fix leaks, improve ventilation, and promptly remove mold-prone materials |

| Relevant Studies | Research shows mold in damp buildings can significantly increase indoor VOC levels and CO₂ concentrations |

| Environmental Impact | Mold-produced gases contribute to indoor air pollution and can affect building materials and structures |

Explore related products

$13.48 $14.13

What You'll Learn

Mold Metabolism and Gas Production

Mold metabolism is a complex process that involves the breakdown of organic matter to release energy, and this process often results in the production of various gases. One of the primary gases produced by mold is carbon dioxide (CO2), which is a byproduct of cellular respiration. During this process, mold spores consume organic materials such as cellulose, starch, and sugars, releasing CO2 as they metabolize these substances. For instance, in a damp, enclosed environment like a basement, mold colonies can significantly increase CO2 levels, sometimes reaching concentrations of 1,000 parts per million (ppm) or higher, compared to the typical outdoor level of around 400 ppm.

Another critical gas produced by mold is volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which are emitted as secondary metabolites during their growth. These VOCs include alcohols, aldehydes, and ketones, and they contribute to the musty odor often associated with mold-infested areas. For example, Stachybotrys chartarum, commonly known as black mold, produces trichothecene mycotoxins and VOCs like 1,3-octadiene, which can be detected at levels as low as 50 parts per billion (ppb) in indoor air. These compounds not only serve as indicators of mold presence but also pose health risks, particularly in poorly ventilated spaces where concentrations can accumulate.

Understanding the conditions that amplify gas production by mold is essential for prevention. Mold thrives in environments with high humidity (above 60%), temperatures between 20°C and 30°C (68°F and 86°F), and abundant organic material. In such conditions, gas production can escalate rapidly. For instance, a study found that mold colonies on water-damaged drywall produced CO2 at rates up to 10 times higher than those on dry materials. Practical steps to mitigate this include maintaining indoor humidity below 50%, promptly repairing water leaks, and ensuring adequate ventilation in areas prone to moisture buildup, such as bathrooms and kitchens.

Comparatively, while CO2 and VOCs are the most commonly discussed gases, mold can also produce trace amounts of other gases like methane (CH4) and hydrogen (H2) under anaerobic conditions. These gases are less significant in typical indoor mold scenarios but highlight the versatility of mold metabolism. For example, in waterlogged environments like flooded basements, mold can switch to anaerobic respiration, producing methane at levels up to 100 ppm. While not a primary concern for most homeowners, this underscores the importance of addressing water damage promptly to prevent such conditions.

In conclusion, mold metabolism and gas production are intrinsic processes that not only indicate mold presence but also contribute to indoor air quality issues. By recognizing the specific gases produced, such as CO2 and VOCs, and understanding the environmental factors that drive their production, individuals can take targeted steps to prevent mold growth. Regular monitoring of humidity levels, prompt remediation of water damage, and improving ventilation are practical measures to minimize gas buildup and maintain a healthy indoor environment.

Extending Mushroom Spores Lifespan: Fridge Storage Tips and Duration

You may want to see also

Types of Gases Released by Mold Spores

Mold spores, when active, release a variety of gases as byproducts of their metabolic processes. One of the most well-documented gases is carbon dioxide (CO₂), which is produced during the respiration of mold. While CO₂ itself is not toxic in small amounts, elevated levels can indicate a significant mold infestation. For instance, indoor CO₂ concentrations above 1,000 parts per million (ppm) may suggest poor ventilation and mold growth, particularly in enclosed spaces like basements or bathrooms. Monitoring CO₂ levels with a portable gas detector can serve as an early warning sign of mold activity, prompting further investigation.

Another gas released by mold spores is methyl mercaptan, a volatile organic compound (VOC) with a distinct "rotten egg" odor. This gas is produced during the breakdown of organic matter by certain mold species, such as *Penicillium* and *Aspergillus*. While methyl mercaptan is detectable at very low concentrations (as little as 1 part per billion), prolonged exposure can cause headaches, dizziness, and respiratory irritation. In industrial settings, this gas is often associated with mold-contaminated insulation or damp wood, making it a critical indicator for occupational health assessments.

Ethanol is another gas emitted by mold spores, particularly during the fermentation of sugars in organic materials like wallpaper or carpet. While ethanol is commonly known for its use in alcoholic beverages, its presence in indoor air can signal mold growth and contribute to poor air quality. At concentrations above 1,000 ppm, ethanol can cause eye and respiratory irritation, though such levels are rare in residential environments. However, even low concentrations can exacerbate allergies or asthma in sensitive individuals, underscoring the importance of addressing mold at the first sign of musty odors or visible growth.

A less commonly discussed gas is hydrogen sulfide (H₂S), which is produced by certain molds under anaerobic conditions, such as in water-damaged drywall or flooded basements. H₂S has a characteristic "rotten egg" smell similar to methyl mercaptan but is far more toxic. Exposure to H₂S at concentrations above 100 ppm can cause immediate respiratory paralysis, while chronic exposure to lower levels (10–20 ppm) can lead to fatigue, memory loss, and respiratory issues. This gas is particularly dangerous because it is heavier than air, accumulating in low-lying areas and posing a risk during cleanup efforts.

Practical steps to mitigate gas buildup from mold spores include improving ventilation, maintaining indoor humidity below 50%, and promptly addressing water leaks or moisture issues. For individuals with mold allergies or respiratory conditions, using HEPA air purifiers and wearing N95 masks during cleanup can reduce exposure to mold-related gases. If mold growth is extensive or gases like H₂S are suspected, professional remediation is strongly recommended to ensure safe and thorough removal. Understanding the types of gases released by mold spores not only aids in early detection but also guides effective prevention and intervention strategies.

Mold Spore Allergies: Breathing Challenges in Humid Environments Explained

You may want to see also

Environmental Factors Affecting Gas Buildup

Mold spores, under certain conditions, can indeed contribute to gas buildup in environments, particularly through their metabolic processes and interactions with organic matter. However, the extent of this gas production is heavily influenced by environmental factors. Understanding these factors is crucial for managing indoor air quality and preventing potential health risks associated with mold and its byproducts.

Humidity and Moisture Levels: The Catalysts for Mold Activity

Mold thrives in environments with relative humidity above 60%, as moisture is essential for spore germination and growth. When organic materials like wood, paper, or fabric become damp, mold colonies metabolize these substrates, releasing gases such as volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and carbon dioxide. For instance, *Stachybotrys chartarum*, a mold associated with water-damaged buildings, produces mycotoxins and gases that can accumulate in enclosed spaces. To mitigate this, maintain indoor humidity below 50% using dehumidifiers, and promptly address water leaks or flooding. Regularly inspect areas prone to moisture, such as basements and bathrooms, to prevent mold colonization.

Temperature: A Double-Edged Sword

Temperature plays a dual role in mold gas production. Optimal growth occurs between 20°C and 30°C (68°F and 86°F), with gas emissions peaking within this range. However, extreme temperatures can temporarily suppress mold activity but may not eliminate spores. For example, heating systems in winter can dry out mold colonies, reducing gas production, but spores remain viable, ready to reactivate when conditions improve. Conversely, warm, humid summers accelerate mold growth and gas buildup. To control this, monitor indoor temperatures and ensure proper ventilation, especially in climates with high humidity or temperature fluctuations.

Ventilation: Diluting the Accumulation

Poor ventilation exacerbates gas buildup by trapping mold emissions in confined spaces. Inadequate air exchange allows gases like VOCs, methane, and hydrogen sulfide to accumulate, posing health risks such as respiratory irritation or headaches. A study by the EPA found that homes with poor ventilation had VOC levels up to 10 times higher than well-ventilated spaces. To improve air quality, use exhaust fans in kitchens and bathrooms, open windows daily for at least 15 minutes, and consider installing air exchange systems. For buildings with persistent mold issues, HEPA filters can capture spores and reduce gas concentrations.

Substrate Availability: Fueling the Process

The type and abundance of organic materials in an environment directly impact mold gas production. Cellulose-rich materials like drywall, carpet, and insulation are prime substrates for mold. For example, a 2018 study showed that mold colonies on gypsum board produced significantly higher levels of VOCs compared to those on concrete. To minimize substrate availability, opt for mold-resistant materials in construction, such as mold-inhibiting paints and moisture-resistant drywall. Regularly clean and declutter areas prone to mold, especially in storage spaces where organic debris can accumulate unnoticed.

Light Exposure: A Natural Inhibitor

Natural light acts as a deterrent to mold growth, as many species are sensitive to ultraviolet (UV) radiation. UV light can degrade mold cell walls and inhibit spore germination, reducing gas production. However, indoor environments often lack sufficient sunlight, particularly in windowless rooms or areas with heavy shading. To harness this effect, maximize natural light exposure by using sheer curtains and strategically placing mirrors to reflect sunlight. In areas where natural light is insufficient, UV-C lamps can be employed, but caution is advised, as prolonged exposure to UV-C can be harmful to humans.

By addressing these environmental factors—humidity, temperature, ventilation, substrate availability, and light exposure—it is possible to significantly reduce mold-related gas buildup. Proactive measures not only improve indoor air quality but also safeguard health and structural integrity. Regular monitoring and maintenance are key to creating an environment hostile to mold proliferation.

Spore's Release Date: A Journey Back to Its Launch in 2008

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$23.99

Health Risks of Mold-Generated Gases

Mold spores, when left unchecked, can produce volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and microbial volatile organic compounds (mVOCs) as byproducts of their metabolic processes. These gases, such as 1-octen-3-ol, 3-methylfuran, and geosmin, are often responsible for the musty odor associated with mold-infested areas. While the smell is a nuisance, the real concern lies in the potential health risks these gases pose, particularly in enclosed spaces with poor ventilation. Prolonged exposure to mold-generated gases has been linked to respiratory issues, headaches, and even neurological symptoms in sensitive individuals.

Consider the case of a family living in a water-damaged home, where mold growth was rampant behind walls and under flooring. Over time, the occupants experienced persistent coughing, sinus congestion, and unexplained fatigue. Air quality testing revealed elevated levels of mVOCs, specifically 3-methylfuran, which is known to irritate the mucous membranes and exacerbate asthma. This example underscores the importance of addressing mold issues promptly, as the cumulative effect of these gases can lead to chronic health problems, particularly in children, the elderly, and those with pre-existing respiratory conditions.

To mitigate health risks, it’s crucial to identify and eliminate mold sources before gas buildup becomes hazardous. Practical steps include maintaining indoor humidity below 60%, promptly repairing leaks, and ensuring proper ventilation in damp areas like bathrooms and basements. For individuals already exposed to mold-generated gases, medical professionals may recommend air purifiers with HEPA and activated carbon filters to reduce VOC levels. In severe cases, professional mold remediation is necessary to safely remove the source and prevent further gas production.

Comparatively, the health risks of mold-generated gases are often overlooked in favor of visible mold growth, but the invisible threat can be just as dangerous. While surface mold can cause allergic reactions, the gases it produces can penetrate deeper into the respiratory system, potentially leading to systemic inflammation. For instance, mycotoxins released by certain molds, such as Stachybotrys chartarum, can become aerosolized and inhaled, causing severe symptoms like pulmonary hemorrhage in infants. This highlights the need for a dual approach: addressing both visible mold and the gases it generates to ensure a safe living environment.

In conclusion, understanding the health risks of mold-generated gases is essential for preventing long-term health complications. By recognizing the signs of mold-related gas buildup—such as persistent odors, unexplained symptoms, or visible mold growth—individuals can take proactive measures to protect themselves and their families. Regular inspections, proper ventilation, and timely remediation are key to minimizing exposure and maintaining indoor air quality. Ignoring this invisible threat could lead to irreversible health damage, making awareness and action paramount.

Discovering Timmask Spores: A Comprehensive Guide to Sourcing and Harvesting

You may want to see also

Methods to Detect and Mitigate Gas Accumulation

Mold spores, under certain conditions, can contribute to gas accumulation, particularly in enclosed environments. This occurs when mold metabolizes organic materials, releasing volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and other gases like carbon dioxide and methane. Detecting and mitigating these gases is crucial to prevent health risks and structural damage. Here’s how to approach this issue systematically.

Detection Methods: Early Warning Systems

Gas accumulation from mold can be identified using portable gas detectors equipped with sensors for VOCs, carbon dioxide, or methane. For instance, devices like the GasAlertMicro 5 PID monitor VOC levels in parts per million (ppm), with alarms set to trigger at 5 ppm for residential areas. Additionally, thermal imaging cameras can detect temperature anomalies caused by microbial activity, indirectly signaling gas buildup. For DIY detection, test kits like the Mold Armor MO200 measure VOCs, though professional-grade equipment is more reliable for precise readings. Regular monitoring in damp, poorly ventilated spaces is essential, as mold thrives in humidity above 60%.

Mitigation Strategies: Active and Passive Approaches

Once detected, gas accumulation requires immediate action. Active mitigation involves improving ventilation by installing exhaust fans or air exchange systems to dilute indoor gas concentrations. For example, a 500 CFM (cubic feet per minute) exhaust fan in a 10x10x8-foot room can reduce VOC levels by 50% within 2 hours. Passive methods include using desiccants like silica gel to absorb moisture, inhibiting mold growth, and applying antimicrobial coatings on surfaces. In severe cases, professional mold remediation may be necessary, involving HEPA filtration and physical removal of contaminated materials.

Preventive Measures: Long-Term Solutions

Preventing gas accumulation starts with moisture control. Maintain indoor humidity below 50% using dehumidifiers, and promptly repair leaks in plumbing or roofing. Regularly inspect HVAC systems for mold growth, especially in ductwork. For construction, use mold-resistant materials like treated drywall and ensure proper insulation to prevent condensation. Educating occupants about the importance of ventilation, such as opening windows during cooking or showering, can significantly reduce mold-related gas buildup.

Health and Safety Considerations: Protecting Occupants

Exposure to mold-generated gases can cause respiratory issues, headaches, and allergic reactions. Vulnerable populations, including children under 5, the elderly, and immunocompromised individuals, are at higher risk. During mitigation, wear N95 respirators and gloves to avoid inhalation of spores or gases. If VOC levels exceed 1,000 ppm, evacuate the area until levels drop. Consult healthcare providers if symptoms persist, and ensure proper documentation of exposure for insurance or legal purposes.

Technological Innovations: Advanced Solutions

Emerging technologies offer promising solutions for gas detection and mitigation. IoT-enabled sensors can monitor environmental conditions in real-time, sending alerts to smartphones when gas levels rise. Photocatalytic oxidation (PCO) air purifiers use UV light to break down VOCs into harmless byproducts, reducing gas accumulation. For large-scale applications, biofilters containing bacteria that metabolize VOCs are effective in industrial settings. These innovations, while costly, provide long-term benefits in maintaining air quality and preventing mold-related issues.

Are Spores Legal in NYC? Understanding the Current Laws and Regulations

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, mold spores can produce gases as part of their metabolic processes, such as volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which contribute to the musty odor often associated with mold growth.

Mold spores release gases like methane, carbon dioxide, and various VOCs, including alcohols, ketones, and aldehydes, depending on the mold species and environmental conditions.

Yes, mold-produced gases, particularly VOCs, can irritate the respiratory system, cause headaches, dizziness, and in severe cases, exacerbate asthma or allergies.

Prevent mold-related gas buildup by controlling indoor humidity (below 60%), fixing leaks promptly, ensuring proper ventilation, and cleaning or removing mold-prone materials like damp carpets or drywall.