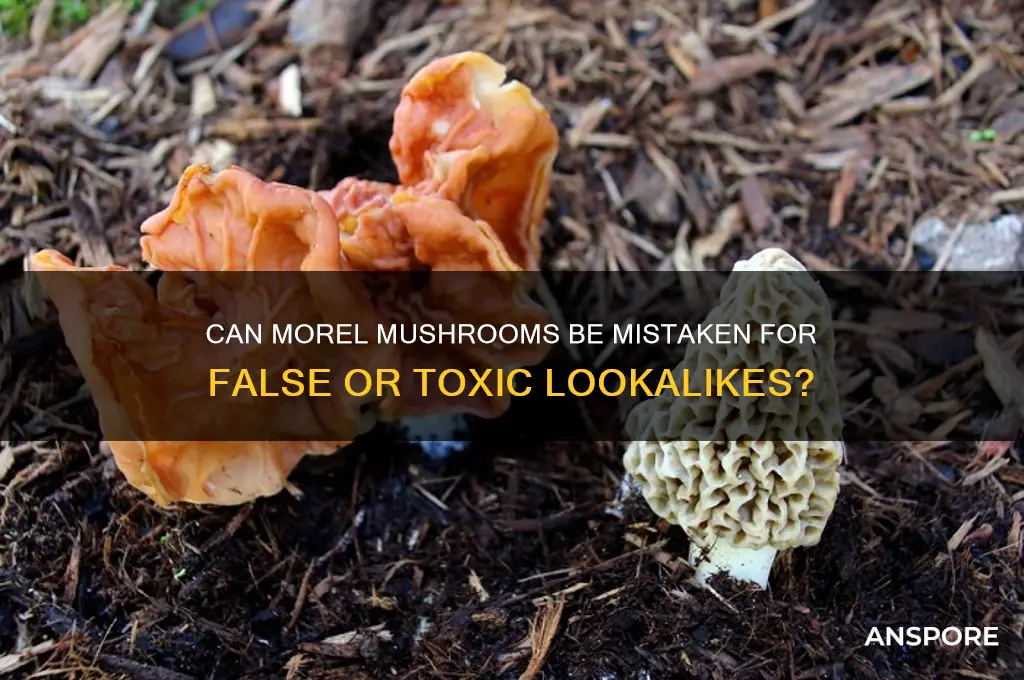

Morel mushrooms are highly prized by foragers and chefs for their unique flavor and texture, but their distinctive honeycomb-like caps and hollow stems can sometimes lead to confusion with other fungi. While true morels are generally easy to identify, novice foragers may mistake them for false morels, such as the gyromitra species, which can be toxic if not properly prepared. Additionally, some poisonous mushrooms, like the early false morel or certain species of verpa, bear a superficial resemblance to morels, posing a risk to those unfamiliar with their subtle differences. Understanding these potential look-alikes and learning to distinguish key features, such as cap structure and spore color, is crucial for safely harvesting and enjoying morels.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Similar-looking false morels: key differences in appearance and potential dangers of misidentification

- Poisonous look-alikes: species like Gyromitra and Verpa often confused with true morels

- Early growth stages: young morels vs. other fungi in similar developmental phases

- Habitat overlaps: environments where morels and toxic mushrooms coexist, increasing misidentification risks

- Color variations: how morel hues can mimic other mushrooms, complicating accurate identification

Similar-looking false morels: key differences in appearance and potential dangers of misidentification

Morel mushrooms, prized for their earthy flavor and distinctive honeycomb caps, are a forager’s treasure. Yet, their doppelgängers—false morels—lurk in the same forests, tempting the unwary. These imposters, particularly species like *Gyromitra esculenta* and *Verpa bohemica*, mimic morels’ appearance but harbor toxins that can cause severe illness or even death if misidentified and consumed. Understanding the subtle yet critical differences in their anatomy is essential for safe foraging.

Key Visual Distinctions: True morels (*Morchella* spp.) have a hollow stem and cap that are fused at the base, creating a seamless, sponge-like structure. False morels, in contrast, often have a brain-like, wrinkled cap and a stem that is either partially hollow or completely solid. *Gyromitra esculenta*, for instance, has a folded, lobed cap that resembles a crumpled brain, while *Verpa bohemica* features a cap that sits atop the stem like an umbrella, leaving a distinct gap. These structural differences are telltale signs of a false morel, but they require careful examination, especially in younger specimens where features are less pronounced.

Toxicity and Risks: False morels contain gyromitrin, a toxin that converts to monomethylhydrazine (MMH) in the body. MMH is a potent toxin that can cause symptoms ranging from gastrointestinal distress (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea) to neurological effects (dizziness, seizures) and, in severe cases, organ failure. Even small quantities—as little as 100 grams of raw *Gyromitra esculenta*—can be dangerous, particularly for children or individuals with lower body weight. Proper identification is non-negotiable, as cooking or drying does not entirely eliminate the toxin, though it can reduce gyromitrin levels by up to 50%.

Practical Tips for Safe Foraging: To avoid misidentification, always cut mushrooms lengthwise to inspect their internal structure. True morels will be completely hollow from cap to stem base, while false morels often have a cottony or partially solid interior. Additionally, carry a field guide or use a reliable mushroom identification app to cross-reference findings. If in doubt, discard the specimen—the risk of poisoning far outweighs the reward of a meal. Foraging with an experienced guide or joining a local mycological society can also provide hands-on learning and reduce the likelihood of errors.

The Takeaway: While morels and false morels may share a habitat and a superficial resemblance, their differences are both visible and vital. Foragers must approach their craft with precision, patience, and respect for the potential dangers of misidentification. By mastering the art of distinction, enthusiasts can safely enjoy the bounty of the forest without falling prey to its pitfalls.

Do Magic Mushrooms Appear in Standard Drug Tests? What to Know

You may want to see also

Poisonous look-alikes: species like Gyromitra and Verpa often confused with true morels

Morel mushrooms, prized by foragers for their distinctive honeycomb caps and rich flavor, are not without their doppelgängers. Among the most notorious imposters are species from the genera *Gyromitra* and *Verpa*, which can deceive even experienced hunters. These look-alikes share superficial similarities with true morels but harbor toxins that can cause severe illness or, in extreme cases, prove fatal. Understanding their differences is critical for anyone venturing into the woods with a basket.

Take *Gyromitra esculenta*, commonly known as the false morel, as a prime example. Unlike true morels, whose caps are hollow, *Gyromitra* species have a brain-like, wrinkled appearance and are often chambered or filled with cottony tissue. Their stems are typically thicker and more substantial, lacking the hollow structure of morels. The danger lies in their toxin, gyromitrin, which breaks down into monomethylhydrazine—a compound used in rocket fuel. Ingesting even small amounts can lead to symptoms like nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. In severe cases, it can cause seizures, liver damage, or death. Proper preparation, such as thorough cooking and discarding the cooking water, can reduce toxicity, but this practice is risky and not recommended for novice foragers.

Verpa bohemica, another common look-alike, is often mistaken for morels due to its similar honeycomb cap. However, Verpa species have a key distinguishing feature: their caps are attached only at the top of the stem, creating a distinct "skirt-like" appearance. True morels, in contrast, have caps that fuse seamlessly to the stem. While Verpa is generally considered less toxic than Gyromitra, it can still cause gastrointestinal distress in sensitive individuals. Foraging guides often advise avoiding Verpa altogether, as its risks outweigh its culinary benefits.

To safely distinguish true morels from their poisonous counterparts, focus on three critical characteristics: cap attachment, stem structure, and overall shape. True morels have a hollow, sponge-like cap that is fully attached to a hollow stem, forming a seamless, conical structure. False morels, like *Gyromitra*, often have a brain-like, wrinkled cap and a solid or chambered stem. *Verpa* species, meanwhile, have a cap that hangs freely from the stem like an umbrella. When in doubt, err on the side of caution—consult a field guide or experienced forager, and never consume a mushroom unless you are absolutely certain of its identity.

The allure of morel hunting lies in its rewards, but it demands respect for the risks involved. Poisonous look-alikes like *Gyromitra* and *Verpa* serve as a reminder that nature’s bounty is not without its pitfalls. By mastering the art of identification and adopting a cautious approach, foragers can enjoy the thrill of the hunt while safeguarding their health. After all, the true prize is not just the mushroom itself, but the knowledge and skill that bring it safely to the table.

Can Dogs Safely Eat Lion's Mane Mushrooms? A Complete Guide

You may want to see also

Early growth stages: young morels vs. other fungi in similar developmental phases

In the early growth stages, young morels can be particularly challenging to identify due to their small size and underdeveloped features. At this phase, they often resemble other fungi, such as the deadly *Galerina marginata* or the less harmful but similarly shaped *Verpa bohemica*. The key to differentiation lies in scrutinizing the stem and cap structures. Young morels typically exhibit a hollow stem and a wrinkled, honeycomb-like cap, whereas *Galerina* has a solid stem and a smooth, bell-shaped cap. *Verpa*, on the other hand, has a distinct cup-like cap that hangs freely from the stem, unlike the morel’s fused cap.

Analyzing the habitat provides another layer of distinction. Morel mushrooms favor deciduous forests with rich, loamy soil, often appearing near trees like elm, ash, or apple. In contrast, *Galerina* thrives in woodchip mulch or decaying wood, while *Verpa* is commonly found in similar forested areas but tends to emerge earlier in the season. Foraging during the correct season and location narrows down the possibilities, but close examination remains crucial. A hand lens can be invaluable for spotting microscopic differences, such as the presence of true gills in *Galerina* versus the morel’s ridged and pitted cap.

A persuasive argument for caution is the potential consequences of misidentification. While young morels are prized for their earthy flavor and meaty texture, consuming *Galerina* can lead to severe liver damage or even death. Even *Verpa*, though not lethal, can cause gastrointestinal distress in some individuals. Therefore, foragers should adhere to the rule: "If in doubt, throw it out." Cooking morels thoroughly is also essential, as raw or undercooked specimens can cause discomfort regardless of species.

Comparatively, the developmental phases of fungi highlight the importance of patience in foraging. Young morels may take 2–3 days to mature fully, during which their distinctive features become more pronounced. In contrast, *Galerina* and *Verpa* progress through their life cycles with less dramatic changes, making early-stage identification even more critical. Foraging guides and mobile apps can aid in this process, but hands-on experience and mentorship remain irreplaceable. Practicing with an experienced forager can help build the skills needed to distinguish these fungi confidently.

Finally, a descriptive approach underscores the sensory cues that differentiate young morels. Their faint earthy aroma and brittle texture when pinched set them apart from the musty smell and tougher consistency of *Galerina*. *Verpa*’s gelatinous stem base is another tactile giveaway. By combining visual, habitat, and sensory observations, foragers can minimize the risk of misidentification. Remember, the goal is not just to find morels but to do so safely, ensuring a rewarding and risk-free foraging experience.

Can Mushrooms Cause Nausea? Understanding Side Effects and Risks

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Habitat overlaps: environments where morels and toxic mushrooms coexist, increasing misidentification risks

Morels and false morels often share the same deciduous forests, particularly those rich in ash, aspen, and oak trees. These environments, characterized by moist soil and decaying wood, create ideal conditions for both edible morels and toxic look-alikes like *Gyromitra esculenta*. Foragers must be vigilant, as the presence of both species in the same habitat increases the risk of misidentification, especially for inexperienced hunters.

To minimize risks, focus on key morphological differences. True morels have a hollow stem and a honeycomb-like cap with distinct pits and ridges, while false morels have a wrinkled, brain-like cap and a cottony, partially solid stem. Always cut mushrooms lengthwise for verification. If unsure, avoid consumption, as false morels contain gyromitrin, a toxin that can cause severe gastrointestinal distress, seizures, or even death in extreme cases.

Foraging in mixed woodlands requires a strategic approach. Start by scouting areas with recent tree disturbances, such as fallen logs or fire-cleared zones, where morels thrive. Carry a field guide or use a reliable mushroom identification app for real-time comparisons. If you encounter a mushroom with a folded, lobed cap or a stem that isn’t completely hollow, discard it immediately. Cross-contamination is another risk; use separate baskets for suspected species until confirmed safe.

Children and pets are particularly vulnerable to accidental poisoning, as even small amounts of gyromitrin can be harmful. Educate family members about the dangers of consuming wild mushrooms without expert verification. If ingestion occurs, seek medical attention promptly, bringing a sample of the mushroom for identification. Time is critical, as symptoms can appear within 6–12 hours.

In habitats where morels and toxic species overlap, the adage “when in doubt, throw it out” is paramount. While the thrill of the hunt is undeniable, the consequences of misidentification far outweigh the rewards. By combining careful observation, education, and caution, foragers can safely enjoy the bounty of these shared environments without risking their health.

Sleeping on Mushrooms: Safe, Risky, or Just a Myth?

You may want to see also

Color variations: how morel hues can mimic other mushrooms, complicating accurate identification

Morel mushrooms, prized for their distinctive honeycomb caps and rich flavor, are not always the uniform brown or tan that foragers expect. Their color spectrum can range from pale yellow to deep gray, even approaching black in some species. This variability is not just a curiosity—it’s a practical challenge. For instance, the *Morchella esculenta* often starts as a pale cream before darkening with age, while *Morchella elata* can present a near-black cap in mature specimens. Such shifts can cause even experienced foragers to hesitate, as these hues overlap with those of false morels like *Gyromitra esculenta*, which contain toxic gyromitrin. The lesson here is clear: color alone is insufficient for identification, and relying solely on this trait can lead to dangerous mistakes.

To navigate this complexity, foragers must adopt a multi-step approach. First, examine the cap’s texture—true morels have a honeycomb pattern with distinct pits and ridges, whereas false morels often appear wrinkled or brain-like. Second, assess the stem—morels have a hollow stem, while false morels typically have a cottony or partially filled interior. Third, consider habitat and seasonality; morels favor deciduous woods in spring, while false morels may appear earlier or in different environments. For beginners, carrying a field guide or using a mushroom identification app can provide real-time verification. Remember, when in doubt, leave it out—no meal is worth the risk of poisoning.

The persuasive argument for caution is rooted in the consequences of misidentification. Gyromitra poisoning, for example, can cause symptoms ranging from gastrointestinal distress to seizures, often within 6–12 hours of ingestion. Even cooking does not fully eliminate gyromitrin, as the toxin can volatilize and recondense in the body. Conversely, true morels are not only safe but also nutritionally dense, containing vitamins D and B12, iron, and antioxidants. This stark contrast underscores the importance of precise identification. Foraging workshops or joining local mycological societies can provide hands-on training, reducing reliance on color as the primary identifier.

Comparatively, the color mimicry of morels is not unique in the fungal kingdom. Chanterelles, for instance, can range from golden yellow to pale white, sometimes resembling the toxic *Omphalotus olearius* (jack-o’-lantern mushroom). However, morels’ color variations are particularly deceptive due to their structural similarity to toxic look-alikes. Unlike chanterelles, which have a distinct fruity aroma and forked gills, morels lack such secondary identifiers beyond texture and stem structure. This makes their color shifts a more critical factor in misidentification, demanding a higher level of scrutiny from foragers.

Descriptively, the hues of morels can be as captivating as they are misleading. A young *Morchella rufobrunnea* might display a reddish-brown cap that deepens to near-black, its ridges catching the sunlight like polished wood. In contrast, a *Morchella angusticeps* could present a pale yellow-brown, almost blending into the forest floor. These natural variations are part of the fungus’s life cycle, influenced by factors like soil pH, moisture, and sunlight exposure. For the forager, this beauty is a double-edged sword—it invites admiration but demands vigilance. By understanding these nuances, one can appreciate morels not just as a culinary treasure but as a testament to nature’s complexity.

Baking Chopped Mushrooms: Tips, Tricks, and Delicious Recipe Ideas

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, morel mushrooms can be mistaken for false morels, which are toxic. Key differences include the cap structure (morels have hollow, sponge-like caps, while false morels have wrinkled, brain-like caps) and the stem (morels have hollow stems, whereas false morels often have cottony or partially filled stems).

Yes, morels can be confused with poisonous mushrooms like the early false morel or the deadly galerina. Always verify the sponge-like cap, hollow stem, and lack of gills or scales to ensure proper identification.

While less common, morels can be confused with other edible mushrooms like the puffball or chanterelle. However, their distinct honeycomb-like cap and hollow structure make them unique and harder to mistake for other edible varieties.

Fresh morels can sometimes be confused with dried morels if not properly hydrated. Dried morels are shriveled and darker, while fresh morels are plump, lighter in color, and have a more vibrant texture. Rehydrating dried morels will help distinguish between the two.