Morels, highly prized by foragers for their unique flavor and texture, are often sought after in the wild, but their resemblance to certain toxic mushrooms raises significant concerns. One such toxic look-alike is the false morel, which can cause severe gastrointestinal distress or even more serious health issues if consumed. Distinguishing between true morels and their poisonous counterparts requires careful observation of characteristics such as cap shape, spore color, and internal structure. Misidentification can lead to dangerous consequences, making it crucial for foragers to educate themselves thoroughly before harvesting. Understanding these differences not only ensures a safe foraging experience but also highlights the importance of caution when dealing with wild mushrooms.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Visual Differences: Distinguishing morels from false morels by cap shape, stem structure, and overall appearance

- Habitat Clues: Identifying safe morel habitats vs. toxic mushroom environments to reduce risk

- Toxic Look-Alikes: Recognizing poisonous species like false morels and their key characteristics

- Edibility Tests: Simple methods to check if a mushroom is safe to consume

- Seasonal Awareness: Understanding when morels grow vs. toxic mushrooms to avoid confusion

Visual Differences: Distinguishing morels from false morels by cap shape, stem structure, and overall appearance

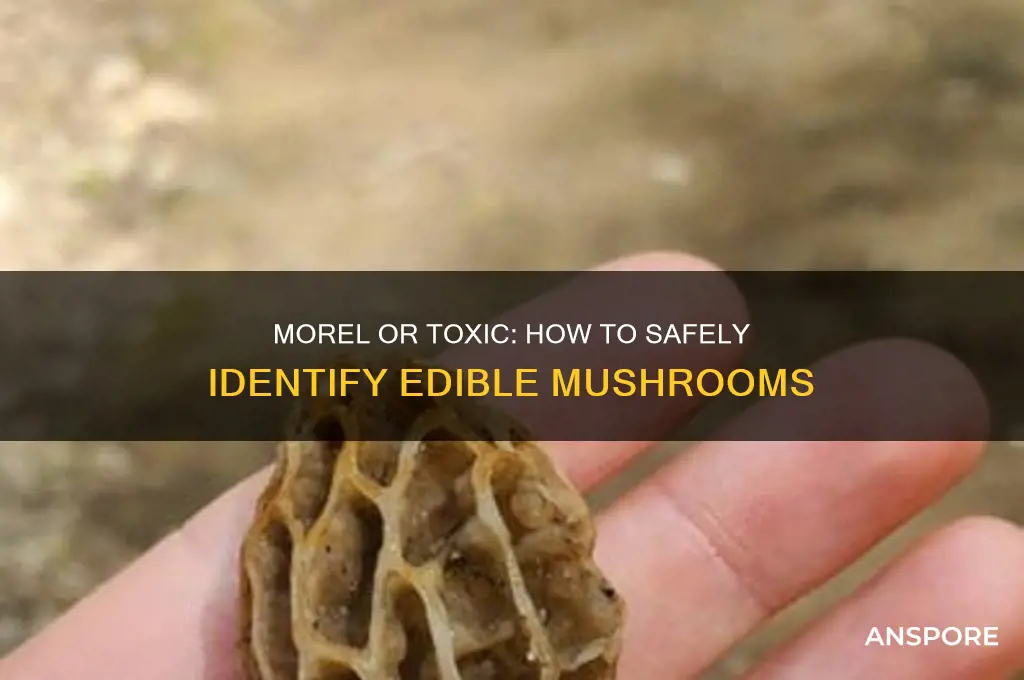

Morels and false morels may both emerge in spring, but their caps tell a stark visual story. True morels boast a honeycomb cap—a network of ridges and pits resembling a sponge or honeycomb. This texture is consistent, with pits that are deep and well-defined. False morels, in contrast, often have a wrinkled, brain-like cap with folds that appear convoluted and irregular. The key distinction lies in the structure: morels’ ridges are raised and distinct, while false morels’ folds seem melted or wavy, lacking the clean, geometric pattern of their edible counterparts.

The stem structure offers another critical clue. Morel stems are hollow from top to bottom, a feature that can be verified by gently breaking one open. False morels, however, typically have stems that are either partially hollow or completely solid. Additionally, morel stems are generally smooth and seamless, blending naturally into the cap. False morels often have stems that appear segmented or swollen, with a less uniform connection to the cap. This difference in stem anatomy is a reliable indicator when visual inspection alone isn’t enough.

Overall appearance plays a pivotal role in identification. Morels stand tall and elegant, with a cap that hangs freely from the stem, creating a distinct separation between the two. False morels, on the other hand, often appear more squat and bulky, with caps that seem to engulf or merge with the stem. Color can also be a subtle cue: morels range from blond to grayish-brown, while false morels may exhibit darker, reddish, or purplish hues. Observing these nuances in shape, proportion, and color can help foragers avoid toxic lookalikes.

For practical application, follow this step-by-step approach: First, examine the cap for a honeycomb pattern versus a brain-like fold. Second, break the stem to check for hollowness. Third, assess the overall posture—does the mushroom appear graceful and distinct, or bulky and fused? Caution is paramount: if unsure, discard the find. False morels contain gyromitrin, a toxin that can cause severe gastrointestinal distress or worse, even in small quantities. Always prioritize visual certainty over culinary curiosity.

Exploring Psilocybin Mushrooms: Legal, Safe, and Ethical Buying Guide

You may want to see also

Habitat Clues: Identifying safe morel habitats vs. toxic mushroom environments to reduce risk

Morels thrive in specific environments that offer clues to their safety. These prized fungi favor disturbed soil, often appearing after forest fires, logging, or near decaying elms. Their preference for well-drained, slightly acidic soil under hardwood trees like ash, oak, and poplar is a key identifier. Toxic mushrooms, however, are less discerning. Many poisonous species, like the deadly Amanita, grow in similar wooded areas but lack the habitat specificity of morels. Recognizing these environmental cues—disturbed soil, hardwood companions, and post-disturbance timing—can significantly reduce the risk of misidentification.

To minimize risk, focus on habitat details. Morels often emerge in spring, coinciding with warming temperatures and moist conditions. They rarely grow in dense clusters; instead, they appear singly or in small groups. Toxic mushrooms, conversely, may grow in large clusters or solitary, with no consistent pattern. Inspect the soil: morels prefer loose, nutrient-rich earth, while some toxic species thrive in richer, undisturbed soil. Note the presence of nearby plants; morels are rarely found near conifers, whereas toxic mushrooms like the Destroying Angel are common in coniferous forests. These subtle habitat differences are critical for safe foraging.

A practical approach involves a three-step habitat assessment. First, observe the soil condition—is it disturbed or pristine? Morel habitats often show signs of human or natural disruption. Second, identify surrounding trees. Hardwoods are morel allies, while conifers signal caution. Third, consider timing and climate. Morels appear in spring with consistent moisture, while toxic mushrooms may emerge year-round. Foraging with a habitat-first mindset shifts focus from mushroom morphology to environmental context, reducing reliance on visual identification alone.

Foraging safely requires more than habitat knowledge; it demands respect for nature’s complexity. Even in ideal morel habitats, verify findings with multiple identification methods. Carry a field guide, use spore prints, and consult experts when unsure. Avoid areas treated with pesticides or near industrial sites, as toxins can accumulate in fungi. Teach children and novice foragers to prioritize habitat clues, emphasizing that "location matters" as much as appearance. By integrating habitat analysis into foraging practice, enthusiasts can enjoy morels while minimizing toxic risks.

Mushrooms and Digestive Discomfort: Unraveling Gas and Bloating Concerns

You may want to see also

Toxic Look-Alikes: Recognizing poisonous species like false morels and their key characteristics

Morels, prized by foragers for their earthy flavor and distinctive honeycomb caps, have a sinister doppelgänger: the false morel. Unlike their edible counterparts, false morels contain gyromitrin, a toxin that breaks down into monomethylhydrazine, a component of rocket fuel. Ingesting even small amounts can lead to symptoms like nausea, vomiting, and in severe cases, seizures or liver damage. Recognizing the differences between these fungi is critical, as misidentification can turn a culinary adventure into a medical emergency.

One key characteristic to look for is the cap structure. True morels have a hollow, sponge-like cap with distinct pits and ridges, resembling a honeycomb. False morels, on the other hand, often have a wrinkled, brain-like appearance with folds that are more convoluted and less defined. Their caps are typically thicker and can be partially or fully fused to the stem, unlike the free-hanging caps of true morels. This distinction is crucial, as it’s one of the most visible differences even to novice foragers.

Another telltale sign is the stem. True morels have a hollow stem that is consistent in shape and color, blending seamlessly with the cap. False morels often have a chunky, uneven stem that may be partially filled or chambered. Additionally, false morels tend to feel heavier and more substantial in the hand due to their denser structure. Foraging guides recommend cutting mushrooms in half to inspect their internal anatomy, a practice that can reveal these critical differences.

Color and habitat also play a role in identification. True morels are typically shades of brown, tan, or yellow, while false morels can range from reddish-brown to nearly black. False morels are often found in areas with disturbed soil, such as recently burned forests or construction sites, whereas true morels prefer undisturbed woodland environments. However, relying solely on habitat is risky, as exceptions do occur. Always cross-reference multiple characteristics before making a decision.

To minimize risk, foragers should adhere to a few practical guidelines. First, never consume a mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity. Second, cook all mushrooms thoroughly, as heat can break down toxins like gyromitrin. Third, start with small quantities when trying a new species, even if it’s confirmed as edible, to test for personal sensitivities. Finally, consult local mycological societies or experienced foragers for hands-on guidance. The allure of wild mushrooms is undeniable, but caution and knowledge are the forager’s best tools.

Can You Eat Dried Mushrooms Raw? Safety and Tips Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$7.62 $14.95

$15.8 $17.99

Edibility Tests: Simple methods to check if a mushroom is safe to consume

Morels, with their distinctive honeycomb caps, are prized by foragers for their earthy flavor and meaty texture. Yet, their resemblance to toxic look-alikes like the false morel (*Gyromitra esculenta*) underscores the critical need for accurate identification. While no single test guarantees edibility, combining several methods can significantly reduce risk.

The Cooking Test: A False Sense of Security

A common myth suggests boiling mushrooms to "remove toxins." While cooking destroys some harmful compounds, it’s ineffective against potent toxins like those in the death cap (*Amanita phalloides*). False morels, for instance, contain gyromitrin, which converts to a toxic compound even when heated. Relying solely on cooking is a dangerous gamble.

Animal Consumption: A Misleading Indicator

Observing animals eat a mushroom is often cited as a safety test. However, animals metabolize toxins differently than humans. Squirrels, deer, and insects may consume toxic species without harm, while the same mushroom can be lethal to humans. This method lacks scientific validity and should never be trusted.

The Universal Edibility Test: A Structured Approach

For survival situations, the Universal Edibility Test offers a cautious, step-by-step process:

- Separation: Isolate a small portion of the mushroom.

- Contact Test: Place a piece on your lip for 15 minutes, then tongue for 15 minutes. Rinse if irritation occurs.

- Ingestion: Chew a small amount and hold in your mouth for 15 minutes. Spit out if adverse reactions occur.

- Delayed Consumption: Wait 8 hours. If no symptoms appear, eat ¼ cup cooked mushroom, waiting another 8 hours.

This method is time-consuming and not foolproof, but it’s a last resort when expert guidance is unavailable.

The Power of Expertise: The Only Reliable Test

No home test—whether rubbing mushrooms on silver, observing color changes, or using store-bought kits—can definitively prove edibility. The only reliable method is accurate identification through field guides, spore prints, and consultation with mycologists. Morel enthusiasts must learn to distinguish true morels from false morels by examining cap attachment (true morels have hollow stems and caps that hang free) and cross-section shapes.

While curiosity drives foraging, caution must drive consumption. When in doubt, throw it out. The forest’s bounty is vast, but its dangers are unforgiving.

Parafilmed Petri Dishes: Safe for Open-Air Mushroom Cultivation?

You may want to see also

Seasonal Awareness: Understanding when morels grow vs. toxic mushrooms to avoid confusion

Morels and toxic mushrooms often share the same habitats, but their growing seasons rarely overlap, offering a critical clue for foragers. Morels typically emerge in spring, favoring cooler temperatures and moist environments after the first warm rains. In contrast, many toxic look-alikes, such as false morels (Gyromitra spp.) or early poisonous species like Amanita, may appear earlier or later, depending on the region. Understanding these temporal differences can significantly reduce the risk of misidentification. For instance, in the northeastern U.S., morels peak in April to June, while false morels often appear slightly earlier, in March to May. This seasonal awareness acts as a first line of defense, narrowing down the possibilities before detailed inspection.

To leverage seasonal awareness effectively, foragers should study regional mushroom calendars and consult local mycological societies. In the Pacific Northwest, morels thrive after forest fires, appearing from April to July, whereas toxic species like the Destroying Angel (Amanita ocreata) emerge in winter months. In Europe, morels are most abundant in May, while the toxic Fool’s Mushroom (Amanita verna) appears in late spring to early summer. Keeping a foraging journal with dates, locations, and species observed can also highlight patterns over time. For beginners, pairing seasonal knowledge with guided foraging trips or apps like iNaturalist can provide real-time verification, ensuring safer harvests.

A comparative analysis of morel and toxic mushroom seasons reveals that while timing is a useful tool, it’s not foolproof. Climate change is altering traditional growing patterns, causing earlier springs and extended seasons in some regions. For example, morels in the Midwest now occasionally appear as early as March, overlapping with false morels. Additionally, some toxic species, like the Jack-O’-Lantern mushroom (Omphalotus olearius), grow in fall, far removed from morel season but still posing risks to inexperienced foragers. Thus, seasonal awareness should complement, not replace, morphological identification skills, such as examining spore color, gill structure, and stem features.

For practical application, consider these steps: First, research the typical morel season in your area, noting temperature and rainfall triggers. Second, cross-reference this with known toxic species’ seasons to identify potential overlaps. Third, if foraging outside the typical morel window, exercise extreme caution and avoid collecting unless absolutely certain. For example, in California, where morels appear after fires, foragers should be wary of Amanita phalloides, which also thrives in disturbed soil but grows year-round. Finally, always cook morels before consumption, as raw morels can cause gastrointestinal distress, and never eat any mushroom without 100% confidence in its identity. Seasonal awareness, combined with these precautions, transforms foraging from a gamble into a rewarding pursuit.

Keto-Friendly Swap: Jarred vs. Fresh Mushrooms in Low-Carb Recipes

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

While morels are generally easy to identify, inexperienced foragers may confuse them with toxic look-alikes like false morels (Gyromitra species) or early-stage poisonous mushrooms. Always verify identification before consuming.

Yes, false morels (Gyromitra species) and some poisonous mushrooms in their early stages can resemble morels. False morels have a brain-like, wrinkled appearance compared to the honeycomb-like structure of true morels.

True morels have a hollow stem and a honeycomb-like cap, while false morels have a wrinkled, brain-like cap and are often partially solid inside. Always consult a field guide or expert if unsure.

Yes, consuming toxic mushrooms like false morels or other poisonous species can cause severe illness or even be fatal. Proper identification is crucial to avoid accidental poisoning.