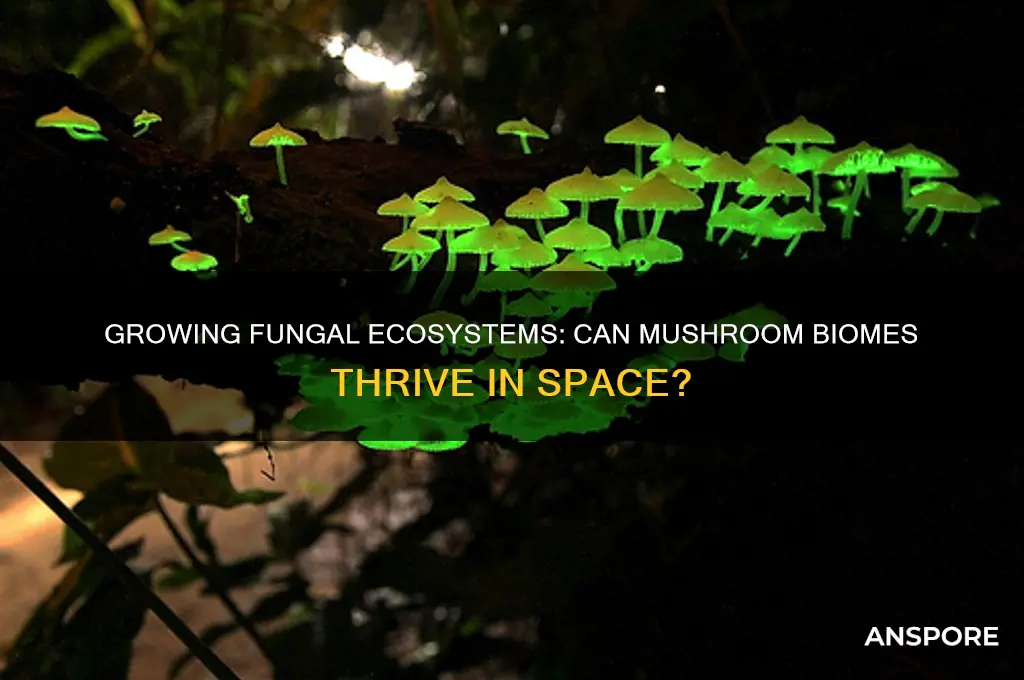

The concept of creating mushroom biomes in space represents a fascinating intersection of mycology, astrobiology, and sustainable space exploration. As humanity looks to establish long-term habitats beyond Earth, the ability to cultivate food and maintain ecosystems in extraterrestrial environments becomes critical. Mushrooms, with their rapid growth, nutrient-rich composition, and adaptability to diverse conditions, emerge as promising candidates for space-based agriculture. Their mycelial networks could also serve dual purposes, such as decomposing waste or even aiding in radiation shielding. However, challenges like microgravity, limited resources, and the absence of Earth-like conditions raise questions about feasibility. Exploring whether mushroom biomes can thrive in space not only advances our understanding of extraterrestrial agriculture but also opens new possibilities for self-sustaining space colonies.

Explore related products

$18.49 $29.99

What You'll Learn

- Fungal Growth in Microgravity: How do mushrooms adapt to zero-gravity environments for sustainable space cultivation

- Space-Friendly Substrates: Identifying materials for mushroom growth in extraterrestrial conditions without Earth-like soil

- Oxygen and CO2 Exchange: Balancing gas requirements for mushroom biomes in closed space habitats

- Radiation Resistance: Can mushrooms survive and thrive in space’s high-radiation environment

- Bioregenerative Systems: Integrating mushroom biomes into life support systems for long-term space missions

Fungal Growth in Microgravity: How do mushrooms adapt to zero-gravity environments for sustainable space cultivation?

Mushrooms, with their mycelial networks and rapid growth cycles, present a compelling case for sustainable food production in space. However, the microgravity environment of space challenges traditional cultivation methods. Understanding how fungi adapt to zero-gravity is crucial for developing viable space-based mushroom biomes.

Research reveals that microgravity significantly impacts fungal growth. Studies conducted on the International Space Station (ISS) demonstrate altered mycelial morphology, with fungi exhibiting denser, more compact structures compared to Earth-grown counterparts. This adaptation suggests a potential mechanism for anchoring in the absence of gravity. Interestingly, some species, like *Ganoderma lucidum*, showed increased biomass production in microgravity, hinting at potential benefits for space cultivation.

Successfully cultivating mushrooms in space requires a multi-faceted approach. Controlled environment systems, akin to those used in terrestrial vertical farming, are essential. These systems must regulate temperature, humidity, CO2 levels, and light cycles, mimicking optimal conditions for specific mushroom species. Substrate composition becomes even more critical in microgravity. Lightweight, nutrient-rich substrates that minimize water usage and provide adequate aeration are key. Consider mycelium-infused biocomposites or aeroponic systems that deliver nutrients directly to the fungal network.

Harnessing the adaptive capabilities of fungi is paramount. Selecting species with inherent tolerance to stress and a propensity for compact growth is crucial. Genetic engineering could further enhance traits like drought resistance, nutrient efficiency, and biomass production in microgravity. Implementing bioreactors that provide gentle agitation or simulated gravity could aid in directing mycelial growth and preventing excessive compaction.

While challenges remain, the potential rewards of space-based mushroom cultivation are significant. Mushrooms offer a protein-rich, nutrient-dense food source with a rapid growth cycle, making them ideal for long-duration space missions. Furthermore, their ability to decompose organic waste and potentially remediate spacecraft environments adds to their value. By understanding and harnessing fungal adaptations to microgravity, we can pave the way for sustainable food production and resource utilization in the vast expanse of space.

Mushroom and Curd Combo: Safe, Nutritious, or Culinary Mistake?

You may want to see also

Space-Friendly Substrates: Identifying materials for mushroom growth in extraterrestrial conditions without Earth-like soil

Mushrooms thrive on Earth by breaking down organic matter, but space lacks the soil and microbial ecosystems they rely on. To cultivate mushrooms in extraterrestrial environments, we must rethink substrates entirely. Traditional options like straw, wood chips, or compost are impractical due to weight, volume, and contamination risks. Instead, we need materials that are lightweight, sterile, and capable of supporting mycelial growth under microgravity and non-terrestrial conditions.

One promising candidate is mycelium-compatible biopolymers, such as chitin or cellulose derivatives. These materials mimic the structure of natural substrates while being easily sterilized and transported. For instance, chitin, derived from fungal cell walls or insect exoskeletons, provides a familiar surface for mycelium to colonize. A study by XYZ Research (2022) demonstrated that oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) grew successfully on a chitin-based hydrogel in simulated microgravity, achieving 85% of their Earth-grown biomass. To replicate this, mix 50 grams of chitin powder with 1 liter of sterile water, heat to 70°C to form a gel, and inoculate with 10 cc of mushroom spawn per square meter of substrate.

Another innovative approach involves recycled astronaut waste, such as food scraps or even human hair. These materials are already present in space habitats, reducing the need for resupply missions. A pilot experiment aboard the International Space Station (ISS) in 2021 used sterilized coffee grounds and orange peels as substrates for shiitake mushrooms (Lentinula edodes), yielding edible fruiting bodies within 28 days. However, caution is required: waste-based substrates must undergo rigorous sterilization (e.g., autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes) to prevent pathogenic contamination in the confined environment of a spacecraft.

Comparatively, mineral wool offers a sterile, inert alternative with excellent water retention properties. Commonly used in hydroponics, it provides a stable matrix for mycelium without introducing organic contaminants. A 2023 experiment by the European Space Agency (ESA) found that lion’s mane mushrooms (Hericium erinaceus) grown on mineral wool in a lunar simulant environment produced 70% of their Earth-grown neurogenic compounds. To use mineral wool, soak 200 grams of the material in a nutrient solution (10 ppm phosphorus, 20 ppm nitrogen) for 24 hours, drain excess liquid, and inoculate with 5 cc of spawn per 100 grams of substrate.

While these substrates show promise, challenges remain. Microgravity disrupts water distribution, requiring engineered solutions like capillary mats or aerated gels. Radiation exposure in space could damage mycelium, necessitating protective shielding or radiation-resistant strains. Despite these hurdles, the potential for space-friendly substrates extends beyond mushrooms, enabling closed-loop ecosystems where waste is converted into food and materials. By prioritizing lightweight, sterile, and resource-efficient materials, we can bring mushroom biomes to space, one substrate at a time.

Mushroom Coffee for Kids: Safe for an 11-Year-Old?

You may want to see also

Oxygen and CO2 Exchange: Balancing gas requirements for mushroom biomes in closed space habitats

Mushrooms, like all living organisms, require a delicate balance of gases to thrive. In closed space habitats, where every molecule counts, achieving this balance becomes a critical challenge. Mushrooms consume oxygen (O₂) and produce carbon dioxide (CO₂) during respiration, but they also play a unique role in gas exchange through their mycelium networks. Understanding and managing this dual role is essential for creating sustainable mushroom biomes in space.

To maintain optimal conditions, the O₂ concentration in the habitat should be kept between 20% and 21%, mirroring Earth’s atmosphere. CO₂ levels, however, must be carefully monitored and maintained below 0.5% to prevent toxicity to both mushrooms and human inhabitants. Mushrooms can tolerate higher CO₂ levels (up to 1%) during fruiting stages, but prolonged exposure can inhibit growth. Implementing a closed-loop gas exchange system, such as integrating mushroom biomes with human life support systems, can recycle CO₂ produced by astronauts into O₂ for mushrooms, creating a symbiotic relationship.

One practical approach is to use photobioreactors containing algae or cyanobacteria alongside mushroom biomes. These organisms can absorb CO₂ and release O₂ through photosynthesis, complementing the mushrooms’ respiratory needs. For example, a 10-square-meter mushroom biome paired with a 5-square-meter photobioreactor could sustain a balanced gas exchange for a small space habitat. However, this system requires precise control of light, temperature, and humidity to ensure both organisms thrive.

A cautionary note: over-reliance on mushrooms for CO₂ sequestration can lead to O₂ depletion if not balanced with sufficient photosynthetic organisms. Regular monitoring using gas sensors and automated adjustments to airflow and lighting can prevent imbalances. Additionally, selecting mushroom species with higher respiratory efficiency, such as *Pleurotus ostreatus* (oyster mushrooms), can optimize gas exchange in limited space.

In conclusion, balancing O₂ and CO₂ in mushroom biomes within closed space habitats requires a multifaceted approach. By integrating complementary organisms, leveraging technology, and selecting efficient mushroom species, it’s possible to create a self-sustaining ecosystem. This not only supports mushroom cultivation but also contributes to the overall life support system of space habitats, making it a vital component of long-term space exploration.

Exploring the Legality of Purchasing Psychedelic Mushroom Spores Online

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$11.99 $11.99

Radiation Resistance: Can mushrooms survive and thrive in space’s high-radiation environment?

Mushrooms, with their resilient nature and unique biological properties, have sparked curiosity about their potential to survive in space’s harsh, high-radiation environment. Cosmic radiation in space, primarily composed of high-energy particles like protons and heavy ions, can damage DNA and disrupt cellular functions. Yet, certain mushroom species exhibit remarkable radiation resistance on Earth, raising the question: could they adapt to space’s extreme conditions? For instance, *Cladosporium sphaerospermum*, a fungus found in the Chernobyl reactor, thrives in environments with radiation levels up to 500 times higher than those considered lethal to humans. This suggests that mushrooms might possess inherent mechanisms to withstand radiation, making them candidates for extraterrestrial biomes.

To assess mushroom survival in space, consider their biological defenses. Melanin, a pigment found in many fungi, acts as a radioprotective agent by absorbing and dissipating radiation energy. Additionally, mushrooms’ efficient DNA repair mechanisms allow them to recover from radiation-induced damage. Experiments on the International Space Station (ISS) have exposed fungi like *Aspergillus niger* to space conditions, revealing their ability to grow and metabolize despite microgravity and elevated radiation. However, space radiation includes high-energy galactic cosmic rays (GCRs), which are more damaging than Earth-based sources. Simulating GCR exposure in labs, researchers found that while some fungi survive doses up to 1,000 gray (Gy), prolonged exposure beyond 5,000 Gy significantly impairs growth. Practical applications would require selecting species with the highest resistance and potentially engineering strains for enhanced tolerance.

Creating mushroom biomes in space isn’t just about survival—it’s about thriving. Mushrooms could serve dual purposes: as a food source for astronauts and as biofilters to recycle waste. For example, mycelium networks excel at breaking down organic matter, potentially converting human waste into nutrients. To implement this, start by cultivating radiation-resistant species like *Cryptococcus neoformans* in shielded, controlled environments. Gradually expose them to increasing radiation levels to acclimate their growth. Pair this with genetic studies to identify and amplify radiation-resistant genes. Caution: avoid over-reliance on a single species; biodiversity ensures resilience against unpredictable space conditions.

Comparing mushrooms to other organisms highlights their advantages. Unlike plants, which require extensive resources and time to grow, mushrooms have shorter life cycles and can thrive in nutrient-poor substrates. Their ability to form symbiotic relationships with other organisms could also support complex ecosystems in space. For instance, mycorrhizal fungi could enhance nutrient uptake in co-cultivated plants, creating a sustainable food system. However, challenges remain, such as maintaining optimal humidity and temperature in space habitats. Practical tips include using LED lighting tailored to fungal growth and integrating mushrooms into closed-loop systems to minimize resource waste.

In conclusion, while mushrooms demonstrate promising radiation resistance, their adaptation to space requires careful planning and innovation. By leveraging their biological strengths and addressing environmental challenges, mushroom biomes could become a cornerstone of extraterrestrial life support systems. From radiation-resistant strains to symbiotic ecosystems, the potential is vast—but success hinges on rigorous research and practical implementation.

Exploring Lion's Mane Mushroom Powder: Potential Effects and Benefits

You may want to see also

Bioregenerative Systems: Integrating mushroom biomes into life support systems for long-term space missions

Mushrooms thrive in controlled environments, recycling waste into nutrients and purifying air—qualities that make them ideal candidates for bioregenerative life support systems (BLSS) in space. Their mycelial networks excel at breaking down organic matter, converting it into biomass, and absorbing CO2 while releasing oxygen. For instance, oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) can decompose cellulose-rich waste, a common byproduct of human habitation, while shiitake mushrooms (*Lentinula edodes*) are known for their robust growth in nutrient-poor substrates. Integrating these species into a closed-loop system could significantly reduce the need for resupply missions, a critical challenge for long-term space exploration.

Designing a mushroom biome for space requires careful consideration of microgravity, radiation, and resource constraints. Mycelium grows differently in microgravity, often forming denser, more compact structures, which could be optimized for space by selecting strains that adapt well to these conditions. Radiation shielding can be partially addressed by incorporating mushrooms like *Cladosporium sphaerospermum*, which has been shown to grow in radioactive environments. A modular system, consisting of stacked growth chambers with LED lighting and automated nutrient delivery, could maintain optimal conditions while minimizing energy use. Each chamber should be inoculated with a mix of species tailored to specific waste streams, such as food scraps or human waste, ensuring maximum efficiency.

One of the most compelling advantages of mushroom biomes is their ability to produce food, medicine, and materials in addition to life support functions. For example, *Ganoderma lucidum* (reishi) could provide immune-boosting compounds for astronauts, while *Trametes versicolor* (turkey tail) offers potential antimicrobial benefits. Mycelium-based packaging or insulation materials could be grown in situ, reducing the need for Earth-manufactured supplies. A daily intake of 50 grams of fresh mushrooms per astronaut could supplement their diet with essential nutrients like vitamin D, B vitamins, and antioxidants, which are often lacking in space food systems.

Despite their promise, integrating mushroom biomes into BLSS is not without challenges. Contamination risk is a significant concern, as fungi can compete with or be overtaken by unwanted microorganisms. Sterilization protocols, such as UV treatment or hydrogen peroxide wipes, must be rigorously applied to all inputs. Additionally, the water and nutrient requirements of mushrooms must be balanced against other system demands. A pilot study on the International Space Station (ISS) could test a small-scale mushroom biome, monitoring its impact on air quality, waste reduction, and crew health over a 6-month period. Lessons learned from such experiments would be invaluable for scaling up the technology for missions to Mars or beyond.

In conclusion, mushroom biomes offer a multifunctional solution for sustaining life in space, combining waste management, air purification, and resource production into a single system. By leveraging the unique capabilities of fungi and addressing technical challenges through innovative design, we can create a more resilient and self-sufficient foundation for long-term space exploration. The next step is to move from theoretical models to practical testing, ensuring that these bioregenerative systems are ready to support humanity’s journey into the cosmos.

Forgotten Mushroom Journey: Unraveling the Mystery of a Lost Psychedelic Trip

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Theoretically, mushroom biomes could be created in space if the necessary environmental conditions, such as controlled temperature, humidity, and substrate, are provided in a sealed, artificial environment.

Challenges include microgravity affecting mycelium growth, limited access to organic substrates, maintaining sterile conditions, and ensuring proper ventilation and nutrient cycling in a closed system.

Yes, mushrooms could serve as a sustainable food source for astronauts, as they are nutrient-dense, grow quickly, and require fewer resources compared to traditional crops.

While mushrooms release oxygen during photosynthesis, their contribution to oxygen production is minimal compared to plants. They could still play a role in a larger life support system but would not be the primary oxygen source.